Financiers vs. Academic Economists

My friend tipped me off to this speech by Charlie Munger that is quite provocative and funny, mostly because he says stuff that only rich old guys can get away with saying. For context, Munger is Vice-Chairman at Berkshire Hathaway, and apparently Warren Buffett refers to Munger as “my partner.” Munger is a self-made man worth more than a billion, who has made many millions of dollars worth of philanthropic donations.

What amused me most was Munger’s discussion of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis:

[E]conomics is in many respects the queen of the soft sciences. It’s expected to be better than the rest. It’s my view that economics is better at the multi-disciplinary stuff than the rest of the soft science. And it’s also my view that it’s still lousy, and I’d like to discuss this failure in this talk. As I talk about strengths and weaknesses in academic economics, one interesting fact you are entitled to know is that I never took a course in economics. And with this striking lack of credentials, you may wonder why I have the chutzpah to be up here giving this talk. The answer is I have a black belt in chutzpah. I was born with it. Some people, like some of the women I know, have a black belt in spending. They were born with that. But what they gave me was a black belt in chutzpah.

…

For a long time there was a Nobel Prize-winning economist who explained Berkshire Hathaway’s success as follows:

First, he said Berkshire beat the market in common stock investing through one sigma of luck, because nobody could beat the market except by luck. This hard-form version of efficient market theory was taught in most schools of economics at the time. People were taught that nobody could beat the market. Next the professor went to two sigmas, and three sigmas, and four sigmas, and when he finally got to six sigmas of luck, people were laughing so hard he stopped doing it.

Then he reversed the explanation 180 degrees. He said, “No, it was still six sigmas, but is was six sigmas of skill.” Well this very sad history demonstrates the truth of Benjamin Franklin’s observation in Poor Richard’s Almanac. If you would persuade, appeal to interest and not to reason. The man changed his view when his incentives made him change it, and not before.

Now to be sure, the PhDs in Chicago and elsewhere can always come up with ways to incorporate the empirical facts into their theory. But that’s the point I have been making for years: In practice, economists believe in the Efficient Markets Hypothesis as a framework with which to interpret the world. That’s not a bad thing per se, but they should stop thinking that they are “letting the data speak for themselves.”

The best example of this was after the financial crash of 2008. There were academic economists and finance guys explaining that the crash just proved how efficient the stock market was! Specifically, Jeremy Siegel argued in the WSJ that, “The EMH, originally put forth by Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago in the 1960s, states that the prices of securities reflect all known information that impacts their value…The fact that the best and brightest on Wall Street made so many mistakes shows how hard it is to beat the market” (italics added).

I hope I don’t need to tell the reader that during the boom years, with executives earning bonuses and “quants” getting paid top dollar to use physics models to price derivatives, people weren’t writing op eds in the WSJ explaining that this success disproved the EMH.

I don’t mean to be too hard on the academic economists who are so enamored with their beautiful theories. Before the financial crisis, I too was far too trusting of our current financial system’s ability to quickly weed out systematic errors, and I thought much more of the Chicago School’s approach to modeling the financial market than I do today. One of the biggest differences between real-world investors and academics is that nothing really bad happens to you if you’re systematically wrong in academia.

Potpourri

==> This essay on “involution” (as opposed to revolution) is interesting, but the best thing is the GIF near the top.

==> On Twitter I said John Urschel provides the perfect natural experiment, to resolve an age-old question: did he have trouble getting a prom date? Nobody liked it. I can’t decide if it’s because they reject stereotypes, or because they didn’t get my joke.

==> I was intrigued to hear that the lady spearheading the movement to replace Andy Jackson on the $20 was fully aware of his opposition to paper money.

==> Dad Mode Activated!

==> Shoot I lost the email of the guy who sent me one of these (the other didn’t want me to use his name)… Anyway this cartoon on the villain economist is funny, and this one on the superhero Sam Harris is hilarious (unless you are an atheist, in which case you’ll think it’s dumb).

==> I personally don’t think right now is the time to be gloating, but if Bitcoin is (say) above $500 five years from now, then this website will be pretty awesome. (For the record, I don’t know when they launched the site; I just came across it this week.) Right now I could understand both fans and haters of Bitcoin feeling confident.

Does Silk Road Refute Rothbardianism?

My latest at FEE. Incidentally, as Jeff Tucker’s comment at the end of the article reminded me, I should have issued a disclaimer: I am stipulating that the message logs are accurate, for the sake of argument. I wanted to show that even if Dread Pirate Roberts did everything that the logs purport, then it is not the death blow to Rothbardianism that people allege. An excerpt:

The most obvious problem with Farrell’s essay is that we’re only having this debate because the state outlaws peaceful markets in marijuana, heroin, cocaine, and other such drugs. Furthermore, the state also prohibits competing, professional agencies for the private production of defense services — this is why DPR thought he had to deal with such unsavory characters. DPR didn’t have the option of, say, taking his case to a reputable private-sector judge and getting a verdict levied against the people attacking Silk Road, because the state renders everything in the Rothbardian vision illegal. Thus, the Silk Road murder-for-hire episode shows what happens when the state interferes in the markets for drugs and law enforcement. In this respect, Farrell’s argument is akin to watching Luke’s tauntaun die on the ice planet Hoth, and then remarking, “This just shows why the galaxy needs an emperor.”

BTW, in case you think, “Yeah yeah, legalize drugs and violence goes way down, I got it,” I promise that’s not the main thrust of my article. I chose the above quote because of the Star Wars line.

I Guess Robert Reich Doesn’t Read Cowen and Tabarrok

…because he’s apparently unaware of the Marginal Revolution. Zing! My latest at Mises CA:

If I still haven’t convinced you, consider it this way: Why stop at education? Surely food and clothing are even more important than formal schooling. So how does the pay of migrant farm and textile workers compare to schoolteachers in the U.S.? I think we need a new federal policy lest we all find ourselves starving and naked.

Paradise Lost

On a recent road trip my son asked me about the doctrine of Original Sin, since it seemed unfair that Adam and Eve got a chance (which they blew), but all of their descendants were born with a curse. Below I’ll distill some of the points I went over with him, since some of you may find them interesting.

==> God knew everything that would happen throughout human history before He even made Adam. Everybody (except Jesus) chooses to sin. There is not a single innocent person (except Jesus), so we don’t need to worry about anybody being threatened with hell for something Adam and Eve did.

==> Even so, my understanding of orthodox Christian doctrine is that yes, there is an important sense in which Adam and Eve had a different type of free will from what every human since them has had. (C.S. Lewis talks about this.)

==> The way I made sense of this was to first talk about the conditions that exacerbate sin. For example (I pointed out to my son), on this trip we had also spent time looking up the biographies of the various supervillains in Batman. Not once did their origin story say, “The Riddler was a happy child who had lots of friends and had a fulfilling career.” No, there were always events involving horrible things–and often cruel acts by others–that helped you understand why that person grew up to be Poison Ivy (or whatever).

Now this is crucial: To walk through such explanations is not to excuse or cancel out the crimes of the supervillains; they really are “bad guys.” But it certainly helps us understand what happened.

Back to the Bible accounts: Everyone after the Fall was born into a broken world, full of pain and sinful people. In such an environment, it is understandable why people would grow up to become expert sinners themselves, since fear and hate are such wonderful motivators to sin.

In contrast, Adam and Eve were literally in paradise. They had no insecurities, no worries about food, no fears of an enemy attack. More so than any other humans,* they had a genuine shot at not sinning.

So if even Adam and Eve couldn’t obey one single rule, you can see how utterly hopeless it is for their descendants. It is in our nature to sin, and in this fallen world, nature will take its course.

* Notice that the one human who escaped this was Jesus–yet He had no insecurities, no worries about food, no fears of an enemy attack. Instead He had complete faith in His Father, and that went hand in hand with His perfect obedience.

Potpourri

==> I haven’t read this yet, but a published response to the “Dark Leviathan” piece that John Bush and I discussed on our recent podcast.

==> At FreedomFest this year, I’m going to be the prosecutor in the “Fed on Trial,” while Jeff Madrick is going to be the defense attorney.

==> Another article on Bitcoin, private law, and all kinds of stuff that I haven’t yet read, but it looks very provocative. Lots of glossy photos!

==> A funny comic on the economics of Superman. I’ll repost my old article on this when they send me the updated URL.

==> FEE publishes Ralph Nader! (Note the date.)

Potpourri

==> I thought this Lew Rockwell podcast about “guilt, shame, and anxiety” was interesting. Now I understand my life…

==> My recent Mises CA post on bank moral hazard and liability for shareholders.

==> Here’s the agenda for the Texas Bitcoin conference, on March 28-29 in Austin. If you use discount code “robertmurphy” you get $25 off.

==> Speaking of Bitcoin, here’s my interview with John Bush. We talk about Silk Road, hitmen, pacifism, the regression theorem, and all kinds of cool stuff…

==> Here’s a good NR article talking about Krugman (and Mike Konczal) pointing at the stands and then the Market Monetarists struck them out. I like this one in particular because it focuses on David Beckworth.

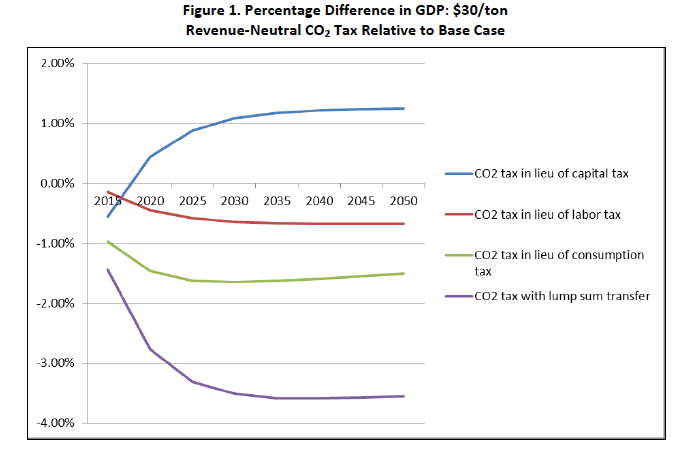

==> My latest at IER shows that even the fans of a carbon tax agree it will hurt the economy, even if 100% of the revenues are recycled back through payroll tax cuts. Look at this chart from a 2013 Resources for the Future (RFF) study:

The next time someone tells you, “Econ 101 says ‘tax bads, not goods,’ duh, a sensibly designed carbon tax swap will help the environment and the economy!” you can show him this chart.

Believing Is Seeing: Noah Smith Reagan Record Edition

Besides my contributions to the rehabilitation of the fine art of karaoke, one of my favorite contributions to humanity is the phrase, “Believing Is Seeing.” (It is self-affirming since many of you probably initially read the post title as, “Seeing Is Believing.”) Today’s example comes from a recent Noah Smith blog post, where Noah wrote:

The U.S. federal deficit, which had been decreasing since the end of WW2, began to trend upward beginning around 1980: [Smith then inserted a chart of federal debt.]

Why? Well, the proximate cause was big tax cuts, without any offsetting spending cuts. The beast was not starved, and tax cuts did not pay for themselves.

Then Noah goes on to give a theory to explain this “fact.” And yet, he never really established the premise of his argument. Even though “everybody knows” that the Reagan Administration ran up huge deficits because of irresponsible “tax cuts for the rich,” it’s not obvious that this is what happened.

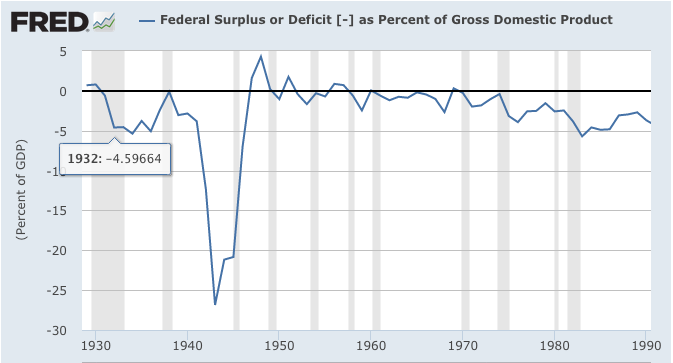

First, let’s look at the federal budget deficit, as a share of the economy, to get a sense of historical context:

There are a few takeaways from the chart above. First, the budget deficits of the Reagan years weren’t unprecedentedly large looking at any year in isolation. For example, they were comparable to the “do-nothing” Herbert Hoover’s budget deficit in 1932, and there were isolated years in the decades following World War II where the deficit was in the same ballpark as the Reagan years after the early 1980s recession. (The deficit sounded unprecedented in the 1980s because people were hearing it quoted in absolute dollar terms, not as a share of the economy.) The reason the federal debt (as a share of the economy) mushroomed so much in the 1980s–as Noah shows in his post–was that there was a consistent string of large deficits; it wasn’t that the deficit in any particular year was that much larger than it had been under previous Administrations.

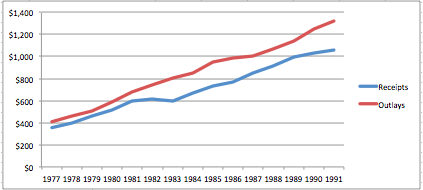

Now let’s look at the level of federal spending and tax receipts (in historical dollars), using the White House historical tables:

The above chart is calibrated in billions of historical (i.e. not inflation-adjusted) dollars. As the data indicate, there was no point during the Reagan years during which federal revenues actually went down. They treaded water for two years during the worst economy since the Great Depression, but then they began rising again.

Now Noah might be tempted to say that the trend under Carter was clearly interrupted by the tax rate reductions of the early 1980s; federal spending continued its typical growth, while receipts never recovered from the shortfall of the recession years.

If that’s how Noah wants to interpret the chart, fair enough, except I would ask that he be consistent. If we use the above chart to rate Carter vs. Reagan, then we should do the same thing with Bush vs. Obama:

To repeat, if Noah thinks it is obvious that the debt problem under Reagan was due to irresponsible tax cuts without comparable spending cuts, then it shouldn’t be a problem for us to find posts from 2009 and 2010 where Noah is decrying the irresponsible tax cuts of the Obama Administration. Indeed, federal tax receipts didn’t even recover to their pre-recession levels until a good three years after Obama took office.

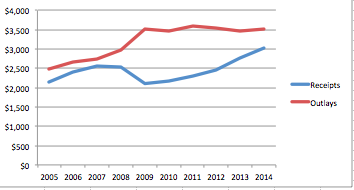

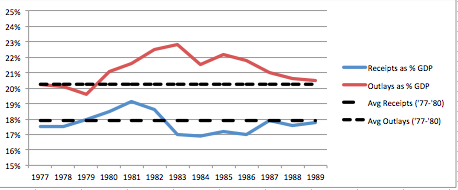

Finally, let’s look at federal outlays and receipts as a percentage of GDP:

The above chart shows that if we compare federal outlays and receipts during the Reagan years to their average values under the Carter years, we conclude the following:

(1) Federal spending under Reagan (as a share of the economy) was consistently and much higher than under Carter.

(2) Federal tax receipts under Reagan (as a share of the economy) were higher during the recession years than under Carter, and for the middle three years were moderately lower than they had been during the Carter years.

So, if you are OK with the way I’ve chosen to slice and dice the data in that last chart, we would reach the exact opposite conclusion from Noah Smith: Namely, the explanation for the explosion of federal debt during the Reagan years is that the federal government took in about the same share of the economy (over the whole period) in receipts, but increased spending.

In conclusion, let me admit that Noah could play with Excel and probably come up with a different way to make his case; there is a lot of wiggle room depending on how we treat Fiscal Year 1981, for example–is that a Carter year or a Reagan year? (Fiscal year 1981 ran from October 1, 1980 through September 30, 1981. Ronald Reagan was elected in November 1980 but not sworn into office until January 20, 1981.) Even harder to evaluate, do we count the big rise in tax receipts as a share of the economy in 1981 and 1982 as due to deliberate policy, or as due to the collapse in economic output during the awful recession?

All I’m trying to do with this post is show that the standard progressive line that the 1980s were due to “tax cuts for the rich” is hard to square with the facts. For sure, it is impossible to simultaneously maintain the progressive narratives regarding Herbert Hoover, Ronald Reagan, and Barack Obama. They would have to adjust their metrics and definitions between presidents for their stories to hold up.

One last thing: I am NOT defending the “Reagan Record” in this blog post. If the Reagan Administration had lived up to the wonderful speeches of the Gipper, then we wouldn’t have these arguments. If President Reagan had actually signed into law massive “spending cuts” as his critics often allege, then nobody would dare suggest that “tax cuts for the rich” had led to a fiscal problem.

Recent Comments