Potpourri

==> The priority deadline is soon approaching if you want to apply for a PhD fellowship to work with us at the Free Market Institute (at Texas Tech). Details here.

==> I offer a useful suggestion to Bryan Caplan and Robin Hanson.

==> I may have already blogged this but: Not all GDP is created equal.

==> Dan Sanchez joins the backlash against the backlash (sic) against Jordan Peterson.

==> Speaking of which, here’s the interview that’s gotten some 3 millions views by this point. I actually don’t think this interviewer was as bad as Peterson’s fans had led me to believe.

Pat and Bob Murphy Perform Krugman Parody on the Contra Cruise

In case it’s not clear, there’s a surprise that occurs while my dad is singing…

What the fork?! Bitcoin vs. Bitcoin Cash

I throw caution to the wind and wade into the debate, with neutrality that would impress the Swiss.

I Push Back Against the Anti-Mercantilists

Don’t worry kids, I’m not angling for a spot in the Trump Administration. But lately I’ve been uncomfortable with some of the standard rhetoric “my side” puts out, regarding free trade and in particular in their critiques of mercantilism.

From p. 279 of Larry White’s (excellent) book The Clash of Economic Ideas, we have this quote from Nassau Senior:

“that extraordinary monument of human absurdity, the Mercantile Theory–or, in other words, the opinion that wealth consists of gold and silver, and may be indefinitely increased by forcing their importation, and preventing their exportation: a theory which has occasioned, and still occasions, more vice, misery, and war, than all other errors put together.”

Now to be sure, I am 100% opposed to mercantilist policies. However, I think sometimes free traders take things too far. It’s NOT a fallacy to think that your nation is richer, OTHER THINGS EQUAL, the more gold and silver it has.

Or at least, it’s no more a fallacy to think that of your nation, that it is to think that of a business or household. And surely not even Nassau Senior (or Don Boudreaux in our time) would tell a business owner, “You’re committing a fallacy if you think your checking account balance is a form of wealth.”

So I think the real problem with mercantilism was not that they thought gold and silver were forms of national wealth, but rather that they may have believed they were the only forms of national wealth, and that they consequently used coercion to artificially accumulate gold and silver at the expense of other desirable outcomes, thus making the nation poorer.

If you doubt me, just keep going back to an individual business. It would be stupid for an outsider to say to the owner, “Hey, I’m gonna help you get richer by punching you in the face every time you try to spend money.” But when you try to explain why it’s stupid, it’s not that you would say, “Because if you just have more money, prices go up; you’re not really any richer.”

Remember your Adam Smith: “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom.” And every family would agree that the household is definitely richer, other things equal, if it has more gold coins. There’s no fallacy involved.

Does Bitcoin Use Too Much Electricity?

My sources say no. My latest at IER. I like this opening:

An optimist says the glass is half full. A pessimist says the glass if half empty. And a Vox writer says if you drink 60 glasses of that stuff in the next hour, it’ll kill you.

A case in point is the recent Vox column by Umair Irfan, warning that the Bitcoin network has caused a huge surge in energy consumption. And yet, Irfan’s own article admits that even the largest estimate—which could be double the actual figure—suggests Bitcoin only uses about 0.14 percent of global electricity. It seems somewhat unfair to single out Bitcoin and ignore the other 99.86 percent of the activities that use electricity.

So Which Are the Predictions That Matter Again…?

Long-time readers know that my day of infamy occurred when I bet David R. Henderson $500 that year/year CPI inflation would break double-digits. (I actually bet Bryan Caplan first, but David’s bet was for a shorter time horizon, so that’s why my bet with David got more attention. I summarize everything here.) When that bet blew up in my face, Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman thought it was the most glorious day since Nixon took us off the gold standard. They were both quite convinced that because I had been wrong in my forecast of (price) inflation, that my underlying model of the economy was wrong, and therefore I needed to reconsider my entire worldview and in particular, my free-market policy recommendations. (All links are provided in the one above.)

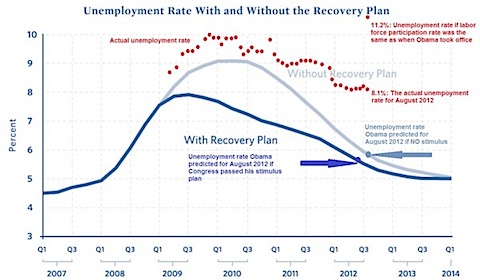

So in that context, I tongue-in-cheek asked about the infamous Romer/Bernstein chart from early 2009, which made projections about the unemployment rate with and without the Obama stimulus package. As it turned out, the unemployment rate *with* stimulus turned out to be worse than what they were warning would happen *without* stimulus:

So I asked (again, tongue-in-cheek) why I had to be taken out to the woodshed for *my* bad prediction, but Romer/Bernstein’s bad unemployment prediction didn’t (apparently) affect the case for deficit spending. Here’s what Krugman said at the time:

Robert Murphy replies to Brad DeLong, and DeLong is not happy — for good reason. But I think there’s also a broader point.

Brad’s ire reflects Murphy’s apparent belief that his failed inflation forecast is OK because we just so happen to have faced a huge deflationary downdraft that offset the inflationary impact of Fed expansion. As Brad says…

My broader point, however, involves Murphy’s main argument, which is “Well, some Keynesians got their unemployment predictions wrong, so there.”

What’s wrong with this line of attack? Two things, actually.

First, it’s really important to distinguish between fundamental predictions of a model and predictions that an economist happens to make that don’t really come from the model. The prediction that huge increases in the monetary base will cause large increases in the price level, and that big government deficits will cause big increases in interest rates, are more or less inescapable if your model of the economy is one in which recessions are supply-side problems, not the result of inadequate demand. Conversely, the prediction that neither of these things will happen if the economy is in a liquidity trap is a fundamental prediction of Keynesian models. On the other hand, the unfortunate Romer-Bernstein prediction of a fairly rapid bounceback from recession reflected judgements about future private spending that had nothing much to do with Keynesian fundamentals, and therefore sheds no light on whether those fundamentals are correct.

In short, some predictions matter more than others. [Bold added.]

OK, so at the time I thought that seemed very convenient for Krugman & Co., namely that unemployment forecasts didn’t matter as much as (price) inflation forecasts, but fair enough. Let’s take Krugman at his word, that it was fatal to my worldview that my model predicted big inflation and it didn’t happen.

Now, EPJ links to a recent symposium on rethinking macro, and Paul Krugman’s contribution has this abstract:

This paper argues that when the financial crisis came policy-makers relied on some version of the Hicksian sticky-price IS-LM as their default model; these models were ‘good enough for government work’. While there have been many incremental changes suggested to the DSGE model, there has been no single ‘big new idea’ because the even simpler IS-LM type models were what worked well. In particular, the policy responses based on IS-LM were appropriate. Specifically, these models generated the insights that large budget deficits would not drive up interest rates and, while the economy remained at the zero lower bound, that very large increases in monetary base wouldn’t be inflationary, and that the multiplier on government spending was greater than 1. The one big exception to this satisfactory understanding was in price behaviour. A large output gap was expected to lead to a large fall in inflation, but did not. If new research is necessary, it is on pricing behaviour. While there was a failure to forecast the crisis, it did not come down to a lack of understanding of possible mechanisms, or of a lack of data, but rather through a lack of attention to the right data.

Well isn’t that special. Here, Krugman the academic says his IS/LM model performed great *except* on the one area of inflation forecasts. Specifically, with unemployment so high and real output below potential output, his model going into the crisis predicted accelerating price deflation, yet we actually observed modest price inflation.

Guy reminds me of Nurse Ratched.

(NOTE: I have previously pointed out Krugman’s inconsistency on these matters, but it’s still fun to comment when he writes a paragraph like the above.)

Dave Smith Interviews Bob

I was just on Dave Smith’s podcast “Part of the Problem.” We talked econ and politics, and had some laughs. Plus near the beginning, I did my dial-up modem sound effect.

Note, I think Dave only has episodes available for free for a short window, so if you want to listen to this, grab it now so you have it.

Recent Comments