There’s Nothing More Complicated Than First Principles

I am not kidding, it is ridiculously hard to express basic economic principles to non-economists. I always felt much more comfortable teaching upper level econ courses to majors.

Case in point: In my latest EconLib, when writing the initial draft, I actually had pangs of doubt that my discussion was so elementary, people would wonder why I wasted their time with truisms.

And yet, the people chiming in at EconLog said my two principles contradicted each other, while the guy chiming in here on Free Advice said my two principles are the same thing.

(BTW, “Transformer” here at the blog is very familiar with economic theory, so that actually might help explain his different reaction.)

Anyway, this is for the professional economists: People objected that it was confusing for me to talk about the gains from specialization, and then to offer a numerical example where the marginal productivity of workers started dropping from the 2nd worker. I.e., I had diminishing marginal returns kicking in right away, so it looked like adding more people always reduced per capita income.

There is actually a lot going on with these examples that is swept under the rug. But, on its own terms, for future reference does it hurt anything if I use numerical examples where the marginal physical product goes up with the first few workers, before maxing out and then falling?

Does a Worker Help the Rest of Society?

In the past on this blog, I’ve complained when Krugman argued that if you believe workers get paid their marginal product, then you can’t also argue that entrepreneurs help the rest of society.

In the current EconLib article, I try to clearly explain at least two major problems with that approach. However, it’s not a Krugman-bashing episode; I agree with him that superficially, it *does* seem that those two (typical free-marketeer) positions contradict each other.

Here’s the intro:

Critics of capitalism have raised many objections to the market economy. For example, Marxists claim that workers are systematically exploited because they are paid less than the full value of their labor. Meanwhile, progressives typically believe that the rich should “give back to the community” that has showered such blessings and privilege upon them.

To be sure, an economist who wishes to defend the virtues of laissez-faire capitalism has well-honed responses to such critiques. Regarding worker pay, it is literally textbook economics to show that so long as there is competition among firms, workers will tend to be paid the “value of their marginal product,” meaning that there is a definite sense in which workers are paid the “full value” of their labor. When it comes to the rich “giving back,” the economist might point to all of the staples of modern life—such as the automobile, telephone, Walmart, and iPhone—that were developed by pioneering entrepreneurs. In a voluntary market setting, the way to get rich is to serve the masses. Indeed, there is a definite sense in which someone’s income is a measure of how much the person has already “given to the community.”

These objections, and the corresponding responses, are typical. And yet, doesn’t it seem that there is at least a tension between them? If it’s true that a worker gets paid an amount just equal to what he or she adds to total economic output, then how can there be any surplus left over to benefit the masses? In particular, suppose that an incredibly productive person decides to drop out of the workforce altogether. Should the rest of society even care, or is it all a wash?

Sincere Question on Tax Reform

I have seen several good economists praising the increase in the standard deduction in the tax package. Now to be clear, even though these are free-market guys, they are *not* simply arguing from the position of, “This reduces theft.” (Indeed, at least two of them are scandalized that employers can still deduct health insurance premiums for their employees.)

So in that context, I’m a bit confused. When I try to explain the basic logic of “flattening the tax code” from a supply-side perspective, I’ll say something like:

“Assume the typical household makes $100,000 in gross income. Under Tax Code A, the household takes $50,000 worth of deductions and pays a marginal tax rate of 40%. Under Tax Code B, the household gets $0 of deductions and pay a marginal tax rate of 20%. With static analysis, the two codes are identical. Yet supply-side economists would say that on efficiency grounds, Tax Code B is clearly preferable. The only reason you might opt for Tax Code A is that some households would make less than $100,000 and you want to build in progressivity, at the expense of muting incentives to generate income among the most productive.”

Am I right in thinking the above is how a supply-side-friendly economist would think? If so, wouldn’t the Republican plan–which doubles the standard deduction while giving piddly rate reductions (on the personal income tax brackets) be the opposite of “reform”?

I am guessing that this is a “second-best” type of argument, where given the existence of a bunch of other itemized deductions that will be politically difficult to eliminate, boosting the standard deduction at least minimizes the “picking winners and losers” element of the tax code (as well as paying CPAs to hunt for deductions). So is that the resolution of this apparent contradiction, or am I totally missing something?

Tolstoy’s *A Confession*

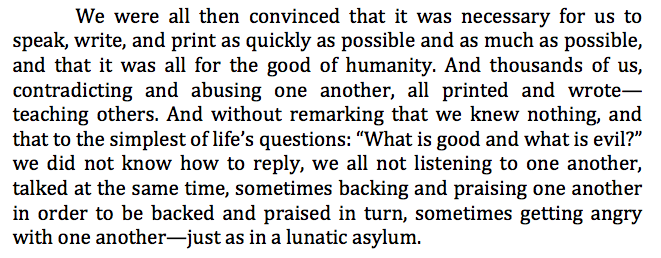

For Christmas I got this work (which Jordan Peterson talks about), as I am a huge fan of The Kingdom of God Is Within You. This passage from early in the book really rang true to me:

I am amazed at how accurately this describes economists today. Here’s a prominent economist arguing that “Money is a veil, and real decisions are (to first order) independent of financial decisions,” and another prominent economist critiques the first by arguing “the corporate tax rate affects per-period after-tax profits in exactly the same way in every period, so there is no effect on the after tax rate of return on investment the firm is facing. Therefore, the firm won’t invest more with a lower corporate tax rate.” I understand the assumptions and model each economist had in mind, and how their statements are true “in context,” but nonetheless those statements on their face are absurd. Just as I’m sure Tolstoy could’ve explained the mindset of each of his literary colleagues in their disputes, where they were huffing and puffing and saying seriously absurd things.

I’m also going through the Chronicles of Narnia with my son. In The Dawn Treader we just covered the adventure where a magician was trying to help these dwarves who think he’s a tyrant, while they do things like wash their forks and knives *before* dinner because they think that saves time.

The older I get, the more convinced I am that the Christian worldview is the only one that gives you an accurate diagnosis of human nature, and the prescription for it. Other paths lead to despair, as Tolstoy’s own discussion exemplifies.

Krugman, I Am Your Father

Things get downright silly in this episode of Contra Krugman where I singlehandedly (Tom’s on vacation) talk about Krugman’s swipes at Bitcoin.

(“What’s with the Vader reference in the title, Bob?” I guess you’ll just have to listen.)

Murphy Links

Some things that have been accumulating; I may have already posted some of them but just in case:

==> My post at IER on coal transportation and the impact on climate policy.

==> Contra Krugman ep. 118: I fly solo, taking on Krugman’s interview with Ezra Klein.

==> My interview on the Libertarian Christian podcast.

Murphy Interview on Conversion and Libertarianism & Christianity

I got into some specifics in this interview that I don’t normally discuss. Probably if you’ve religiously (ha ha) read my religious posts over the years, you have heard all of this, but I don’t usually tell the story in one sitting.

We then move on to standard issues on the possible tension between libertarianism and Christianity.

Murphy 1, Shoguns 0

Regarding my recent debate on the Tom Woods Show with Todd Lewis–regarding private defense–I got the following email (permission to reprint):

Dr. Murphy,

Following your recent debate with Todd Lewis I felt motivated to write the following based on my experience of living in Japan and studying its martial history for over 24 years.

Best regards,

—

Tim Haffner

Why Japan’s Sengoku period does not support monopoly security provision and actually makes the case for the private production of defense:

1. Feudal Japan was a peasant-based agrarian economy overseen by samurai landlords enforcing law and securing territory, ostensibly at least, on behalf of the emperor. Controlling land and the agriculture products yielded from the peasant farmers was essential to power. Taxation and trade were denominated in units of rice bushels. Modes of production, means of commerce, and centers of power have changed significantly since that time. One must be careful and selective when comparing pre-industrial revolution societies with modern theories of political-economy.

2. Japanese people believed the emperor was the living descendant of the Sun Goddess and the unitary source of justice and prosperity. Samurai were fighting amongst each other to be the instrument of his law and reign, implementing the Mandate Of Heaven (a term borrowed from the tyrannical rule in China, see McCaffrey’s 08/22/17 article). The existence of, and belief in, this central authority is what kept up the “game of thrones” with various factions within the court nobility employing their personally hired samurai war band to jockey for position, influence, and income.

3. Samurai started as tax collectors and territorial administrators, land-lording over the peasant farmers in the provinces, on behalf of and in the private employment of, competing nobles within the emperor’s court. An excess of male heirs within the imperial family, and dwindling financial resources, led to many royals renouncing their claims so as to take up positions in the countryside. It was better to be a big fish in a small pond, than fight for scraps in the capital. These dispossessed princes-cum-warriors also served the interests of influential court nobles who were looking to increase their holdings in the countryside while staying close to the flagpole. Again, private alliances serving private interests, yet acting on behalf of state power.

4. Samurai clans operated as corporate bodies that formed alliances for mutual security and specific, central court sanctioned, police actions. The first “Shogun” was a temporary post established to fight back the native populations that were attacking frontier settlements. It was only after the central court’s corruption and failure to impartially render justice in inheritance and land disputes that samurai, such as Taira no Masakado, started rebelling. In the words of JayZ: “The industry is shady, you need to be taking over”. Appealing to a monopolist led to diminished qualities of justice, and attendant dissatisfaction by those with the means to do something about it that started the various periods of civil war.

5. Unification brought the invasion of Korea to keep the samurai alliances occupied and financially depleted while Toyotomi Hideyoshi solidified control over the island nation. Rather than pacifying Japan, monopoly only created negative externalities for Japan’s neighbors. Further, Hideyoshi implemented a “sword hunt” to disarm the population, a census that later tied peasants to the land such that they could not move without permission, and locked people into one of four classes that would stifle economic mobility. Classic moves among all tyrants.

6. When power later passed, violently at the battle of Sekigahara, to the Tokugawa Shoguns, keeping the samurai financially depleted took the form of pre-occupation with ceremonies, bureaucratic formalities, and maintaining alternate residences between the localities and the capital. Wasteful spending mandated by government on useless endeavors is a typical theme in monopoly states. All of which impoverishes the people supporting this kind of wasteful security system.

7. The utility of having aristocratic warriors went down while the costs continually increased. The number of warrior-bureaucrats expanded while actual security providers went down (a bloated tooth to tail ratio). These positions would have been shed, leaving the surplus of labor available for productive activities had the classes not been solidified and people been free to change vocations. Many samurai actually forgot their martial skills and neglected training for combat once accustomed to bureaucratic life and earning their livings through sycophancy. Others, led desperate lives trying to earn money covertly or as bandits and mercenaries once dismissed from service. Tales of “ronin” are notorious for depicting the negative side of “anarchy” under Tokugawa rule.

8. The Tokugawa Shogunate is better viewed as a federal structure that assumed control of external defense and limited dispute resolution, in the name of the emperor, while the internal workings of the provinces and domains were left to the various clans. Once fulfilling its obligation to the Tokugawa regime, a province was free to set its own tax rates, develop its own industries, and manage its affairs as it saw fit. Provinces were actually referred to with the same terms, “kuni”, as those used for foreign nations, including China and Korea.

9. The Tokugawa regime immediately began spending beyond its means, running deficits, and debasing the currency. The quality of life for the average Japanese peasant remained impoverished and displaced samurai turned to crime when they lost employment yet could not pursue work outside of their designated class.

10. The supposed peace brought about by the Tokugawa Shoguns is rightly viewed as the beginning of the end of innovation for Japan as the country was closed off from trade, new ideas, and technologies. This ultimately made Japan vulnerable to invasion, colonialism, and military weakness when Western Imperialism made it to Asia in the 1840’s. Japan could not defend its coast from foreign invaders or even negotiate trade relations with external powers because of the martial decrepitude festering in the Tokugawa bureaucracy that had been wrongly trusted with external security.

11. Even internally the quality and scope of security and justice diminished under monopoly rule under the Tokugawa. For instance, and even within the same province as the Tokugawa seat of power (what is now Tokyo) the farmer population just a few miles outside of the capital were encouraged (despite the class restrictions) to take up the martial arts because resources were unavailable to police the rural areas.

12. In 1853, when American Black Ships under Commodore Perry forced Japan into opening trade relations with the West, the military weakness of the Tokugawa became apparent and the regime began a slow motion implosion while trying to hold its position. From a security standpoint, each clan had to fend for itself and many implemented “minpeitai” militia units to augment the security needs the samurai were unable to provide.

13. Several forward thinking samurai started their own private schools of Western learning and military science. Many called for free trade as a means of acquiring the wealth necessary to develop weaponry sufficient to prevent falling prey to colonial powers like what they were witnessing in China. One samurai, Sakamoto Ryoma, had his own private navy and specialized in smuggling weaponry into the hands of other samurai organized private militia, aimed at overthrowing the inept Tokugawa regime while expelling foreign colonizers. So while the bureaucracy bickered amongst itself, innovative warrior-entrepreneurs were taking action.

14. When the Western backed Imperial forces chased these samurai visionaries to the furthest reaches of the land, they tried to establish an autonomous republic, which would still swear allegiance to the emperor, and held Japan’s first ever popular election. Of course this had to be crushed.

15. Solidifying control under the restored imperial structure and, mirroring what Toyotomi did once achieving hegemony, led to external invasions, the creation of the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to mimic Western colonialism, and an eventual conflict from which Japan has yet to recover. (The people have been disarmed, emasculated, and still live under foreign occupation after all).

Summary: Rather than using Japan’s Warring States period as an example of why compulsory monopoly is necessary for national defense it should rightly be viewed as a warning. Despite the exorbitant costs heaped upon the actual productive segments of the population, paying for a bloated and incompetent bureaucracy did not yield the security promised and eventually every person and territory had to make their own arrangements.

Satisfying the peoples’ security needs eventually reverted back to a mixture of self-help, defensive alliances, and entrepreneurial services anyway, so why not organize for it?

Recent Comments