Quick Clarification on the Great Debt Debate

My trip to NY has messed me up vis-a-vis my “day job” and so I can’t go nuts on the debt debate the way Nick Rowe is (here, here, here, and here). I hope later in the week to offer two more posts, one for the lay reader, and the other for professional economists. It is obvious to me that a lot of people in this debate “still don’t get it.”

The reason I am so confident that I am seeing the divisions more clearly than most, is that I would have agreed with Dean Baker and Paul Krugman two years ago. In fact, I actually wrote up exactly their perspective in both The Politically Incorrect Guide to Capitalism and Lessons for the Young Economist. So this isn’t an ideological issue. In those outlets, my point wasn’t to say, “Government debt is innocuous.” Rather, my point was to say, “The way government debt hurts future generations is through crowding out of private sector investment in the present, meaning our grandchildren inherit fewer tractors and other capital goods.” I now realize that I was wrong for thinking this, and it was Nick Rowe (last year when we had this debate) who freed me from my error.

This time around, when Scott Sumner says he doesn’t see what the big deal is, or Steve Landsburg thinks that Krugman has it almost, but not quite, right, I am pretty sure what’s going on is that Scott and Steve have always thought about this stuff the proper way. It’s somewhat similar to the arguments they use about income vs. consumption taxes, and so it doesn’t surprise me that they have always thought about intergenerational consumption paths and financing options in a correct way.

But Dean Baker and Paul Krugman have been thinking about it the wrong way. That is why they keep focusing (erroneously) on whether the future government debt is held by foreigners vs. Americans. To Landsburg, this is some inexplicable tic on Krugman’s part. Landsburg knows that the ownership of the debt is irrelevant if you are thinking about it properly. So when Krugman says (paraphrasing), “The debt won’t hurt our grandkids so long as foreigners don’t own the Treasuries,” Landsburg just hears, “The debt won’t hurt out grandkids” and gives Krugman a high-five.

Let me be more specific, because it was just today that I realized more precisely why everybody is having such a hard time figuring out who is saying what:

==> Dean Baker and Paul Krugman have been arguing that today’s deficits don’t impoverish our grandkids, so long as the future taxes on our grandkids needed to finance the larger debt are used to give money to some of our grandkids (the bondholders at that time).

==> Steve Landsburg (and I think Scott Sumner, Gene Callahan, Noahpinion, Daniel Kuehn, and maybe some others) have been pointing out that today’s deficits per se don’t make our grandkids poorer. Rather, it’s the taxes that the government will levy on our grandkids, that will make them worse off, in gross terms. (Perhaps these gross harms from the future taxation will be offset by benefits in the form of more bridges, universities, or avoided invasions from Martians. But the higher taxes necessary to finance today’s deficits will definitely be a gross burden on our grandkids.)

==> Nick Rowe and I have been pointing out that the above two camps are NOT “basically saying the same thing.” Go read the two arrows above if it’s not jumping out at you. Reading quickly, they sound similar, but they are vastly different statements.

Part of the problem with this is that the people pushing the “we owe it to ourselves so it’s not a burden” fallacy, are bringing up all sorts of other arguments too. Thus, since some of their other arguments are plausible, it muddies the debate and people aren’t getting the narrow (yet crucial) point that Nick Rowe and I have been patiently making for more than a year now.

To see that we’re not inventing strawmen, look: Here is Dean Baker himself summarizing–as late as Friday, October 12, after Nick Rowe and Brad DeLong went head-to-head–what his position has been:

I saw that Nick Rowe was unhappy that I was saying that the government debt is not a burden to future generations since they will also own the debt as an asset. I had planned to write a response, but I see that Brad DeLong got there first. I would agree with pretty much everything Brad said. The burden of the debt only exists if there is reason to believe that debt is somehow displacing investment in private capital, which is certainly not true at present. [Bold added.]

So Nick Rowe and I continue our valiant crusade, because the part I put in bold above–which Dean Baker himself summarized as his contribution to this whole debate–is TOTALLY WRONG. It’s precisely because Dean Baker continues to write false statements like the above, that Nick Rowe keeps generating very simplistic counterexamples to show why Dean Baker is totally wrong when he keeps saying stuff like this. When the critic asks Nick, “Why don’t you have capital in your model?” Nick’s obvious response is, “Because Dean Baker thinks the debt is only a burden with crowding out. So I’m showing him an example of a debt burden where there is no capital at all! Aaaaaagh!”

Admission of Error Is a Rarity in the Geeconosphere

[UPDATE: I swapped out one of the arguments in light of re-reading Glasner and realizing I misunderstood one of his defenses.]

Consider the following hypothetical argument:

DAVIE: Man, that George Lucas doesn’t have anything to teach us about redemption. If you watch his classic Star Wars movies, he offers a warning about people succumbing to the Dark Side, but offers no guidance on how they can turn back to good.

BOBBY: What the heck are you talking about? In Return of the Jedi, Vader rescues Luke. Then his spirit is reunited in the afterlife with Yoda and Ben Kenobi. We see that one of the major themes of the entire saga is the fall and restoration of Anakin. I am stunned that someone could watch these movies and have uttered your initial statement.

DAVIE: Hmm, I’ve rewatched the sage in light of your clever riposte, Bobby, and now I realize that Lucas contradicted himself. I have a series of points to make, in defense of my original statement:

==>Yes, you’re right that Vader does perform some good deeds in Episode VI, but that’s really just a specific outcome in the fictitious world Lucas has developed. We don’t get a general theory of human redemption, applicable to the real world. For example, Lucas doesn’t work in a scene where Lucas’ own father turns back to good, after slaughtering thousands of rebels.

==>Yes Lucas offers a theme of redemption, but he bashes us over the head with it! He basically just asserts, out of nowhere, that Vader turns back to good, without giving a gradual buildup and character transformation. Classic Lucas.

==>Of course I agree that Lucas in Episode VI has offered us guidance on redemption from evil, but Victor Hugo did a much better job in Les Miserables. Lucas hasn’t taught us anything we didn’t already know.

I submit that if Bobby at this point pulled out a gun and shot Davie squarely between the eyes, no red-blooded jury of Americans would convict him.

Now then, on a completely unrelated note, let’s walk through my paraphrase of David Glasner’s recent thoughts on the work of Ludwig von Mises:

GLASNER: Mises doesn’t give us a theory of why the boom is physically unsustainable. If you read his classic work (Theory of Money and Credit), you’ll see that he offers just a theory applicable to the classical gold standard.

MURPHY: What the heck are you talking about? Mises does indeed give physical reasons for the unsustainability of the artificial boom, and he explicitly warns the reader not to walk away with the view you just attributed to him. I am stunned that someone could have read Mises’ book and still blogged your initial statement.

GLASNER: Upon further re-reading of Mises, I now see that he contradicted himself. Here are some points in defense of my original post:

==>Sure, Mises, writing in 1912, does discuss a hypothetical world where the classical gold standard doesn’t operate, and he does offer a theory as to why a credit expansion even in this world would be physically unsustainable. But, I wanted Mises in 1912 to write from firsthand experience as to why a world not operating under the classical gold standard couldn’t engineer a perpetual credit expansion. He gave us no such analysis, in 1912.

==>Yes, Mises does indeed explicitly state the claim that I said he never made. But, he doesn’t give a good reason for it. He just asserts it and moves on. Classic Mises.

==>Yes, I agree with Murphy that Mises gave a perfectly correct explanation for why a credit expansion–even in a world of fiat money–would eventually come to an end, namely hyperinflation. But we knew that before Mises told us. No contribution from “Austrian business cycle theory” on that score.

It’s a good thing for Glasner that I am a pacifist.

Does Metaphysics Matter?

Suppose you started your day the way you always had the last 20 years, thinking that reality itself is the result of realizations of random variables, and that the only reason life is possible in this universe is that it is one of an infinite number of possible universes.

Then, at lunchtime, you somehow become convinced that there is only one universe, which had a definite beginning and which will have a definite end, and that every event in the history of this universe was designed by a conscious being who is telling a story.

Would that make you live your life differently? Or would this change in perspective be akin to your evolving views on dessert and music?

Curb Your Anticipation

Sorry folks, I have to finish grading…I promised my students. With the LibertyFest activities tomorrow (I’m attending, not speaking) I had better knock it out today.

In the meantime, let me say the following of my two-front war which will soon open to three:

==> Everyone thinks Steve Landsburg is nuts, but actually his case is pretty strong. We’re just arguing over empirical magnitudes at this point.

==> Everyone except George Selgin thinks David Glasner is holding his own against me. No, I absolutely destroyed him on the narrow point under discussion. It’s frustrating that not everyone realizes this.

==> Dean Baker is being saucy and pretending that Nick Rowe had nothing useful to say on the “debt doesn’t burden grandchildren” stuff last year. DeLong has ended his neutrality and has joined forces with the Axis of Obfuscation.

OK if you are a casual passerby, this post means nothing to you. Consider yourself lucky. I will write more coherently after grading…

Harold Hotelling and Steve Landsburg vs Bob Murphy and George W. Bush

It doesn’t look good for me, does it? But give me a chance:

During his commentary on the first presidential debate, Steve Landsburg wrote:

6) Romney says “all of the increase in energy has been on private land, not govt land”. Very ignorant. If there were more drilling on govt land, there’d be less on private land (assuming there’s any truth at all to Hotelling style models and how can there not be?)

In case you want context for Romney’s claim, check out this IER blog post.

In the comments I said to Steve:

Steve, what’s your problem on #6? You don’t think it’s relevant that Obama is taking credit for a rise in domestic oil production, that occurred precisely on those areas where he doesn’t control? (I’m assuming Romney’s basic stat was right.)

Did Romney say, “Now if you had allowed for more drilling on federal land, Mr. President, then in the new general equilibrium, production on private land would have followed the same path”? Maybe he thinks that, but he didn’t say it, and total output would certainly be higher (and spot price of crude would currently be lower) if Obama gave green light to unrestricted drilling on federal land. So why was Romney’s response so ignorant?

Then Steve answered me in the comments by writing:

I don’t get [your claim about oil prices, Bob]. Oil is an exhaustible resource. Allowing drilling on federal land does not change the supply of oil and it does not change the demand for oil, so how can it change the price of oil?

Or to put this another way: Hotelling tells us that in the absence of supply and/or demand shocks, the price of oil has to rise at the rate of interest. The rate of interest is what it is, and doesn’t change just because part of the oil supply moves from below-ground to above-ground. So the path of oil prices is determined independent of whether you allow drilling on federal lands.

(The only exception would be if the President is capable of instituting a *permanent* ban on drilling, effectively taking the oil under that land out of the oil supply. But surely nobody believes that the current President can set drilling policy for 30 years in the future.)

Steve is referring to Harold Hotelling’s classic 1931 article on the economics of exhaustible resources (The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 39, pp. 137-175). With your permission, I will quote from my EconLib article on oil prices to understand Hotelling’s framework:

Assume that every last drop of oil in the world is conveniently located at the surface of the earth, dispersed among thousands of small pools, each of which is owned by a different individual. Each of these owners—who controls a tiny fraction of the world’s total stockpile of oil—knows exactly how big his own pool is, and the pools of oil owned by his competitors. Further suppose that it costs each owner virtually nothing to extract a barrel of oil and sell it on the market. Assume also that the cost of storing the oil is zero, and further that each owner can predict with perfect foresight the demand for oil at every date into the future. There is no doubt that the known oil in the various pools is the only oil that will ever be available. Finally, suppose that each owner is also quite confident that there will always be people wishing to buy some barrels of oil, for virtually any price, into the foreseeable future. Under these very unrealistic yet convenient assumptions, what can we say about the price of oil?

Harold Hotelling provided the elegant answer back in 1931. On the margin, an owner of the oil must be indifferent between selling an extra barrel of oil today—and earning the spot price—versus holding it off the market and selling it in the future. Since we have assumed away storage and extraction costs, and any risk that the quantity demanded of oil will drop to zero if the price rises too far, we can conclude that the spot price of oil (the spot price is the current price at any given time) must rise over time with the interest rate. For example, if a barrel of oil sells today for $100, and the interest rate is 5%, the spot price of oil in twelve months’ time must be $105 in order to make it worthwhile for the owner to keep some oil off of the market today and carry it forward to next year. The idea is that the amount he earns by having the oil sit in the ground must equal the amount he would earn in interest on a portfolio of bonds.

…

Of course, Hotelling’s Rule doesn’t tell us what the actual spot price is at any time; it merely tells us how quickly it must rise. To come up with the specific numbers, we would need to know the demand for oil over time. In a general equilibrium, the spot price would rise with the interest rate (Hotelling’s Rule) and consumers of oil would purchase their optimal number of barrels per day (depending on the price at the time), such that the total consumption into the future would just equal the original size of the pool.

I know there were some scoffers in the comments–both at Steve’s blog and here at Free Advice–who thought Steve was nuts for not seeing how a federal quasi-ban on oil development in certain areas is a leftward shift of the supply curve. But let’s be fair to Steve: What I think he’s arguing is that Obama can only postpone the development of oil in ANWR, offshore, etc. So in the new equilibrium, oil producers in Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Canada, and even in the US on private or state-controlled lands will just ramp up their production rate accordingly. Rather than oil flowing evenly from ANWR, Venezuela, and Canada in 2012 and also in 2042, instead we draw more quickly from Venezuela and Canada and not at all from ANWR in 2012, and then we draw less from Venezuela and Canada but more from ANWR in 2042. (That is an awful sentence but if you read it twice you will get what I’m saying.)

Needless to say, I think Steve is wrong on this. Let me give some quick reasons:

First, I defy Steve to dot the i’s and cross the t’s on the framework at which he is hinting in his remarks. He’s perfectly right, Obama can’t tie policymakers’ hands for the next 30 years. So let’s set up a general equilibrium model in which there is a fixed pool of oil (much much larger than the current “known reserves” value because oil companies only go out and look for more known reserves when it is profitable to do so) as well as a known demand schedule for oil, and where the spot price is set in a Hotelling framework.

However, let’s make a few tweaks for the sake of realism. Assume there is a random variable to determine whether ANWR and other federal lands are off- or on-limits for development in the ensuing decade. Furthermore, assume that the (known) planetary demand curve for oil starts shifting left in the year 2150, because other technologies have more than offset the growth in population and per capita energy consumption. By 2200 the global demand for oil is zero.

I think if you put in reasonable assumptions about the lag between getting the green-light and then the actual pumping of oil from ANWR etc., and further you make reasonable assumptions about the maximum rate of extraction (or if you want to get fancier, you have a rising marginal cost of extraction based on the extraction rate per well), then you would find in the general equilibrium, spot oil prices would fall (meaning current global oil extraction would increase) whenever the random variable had a “green light” realization. This would be true immediately, even during the start-up lag, because the other producers would forecast lower (future) spot prices and would ramp up their current production rates accordingly to maximize the present-discounted value of their operation in light of the new information.

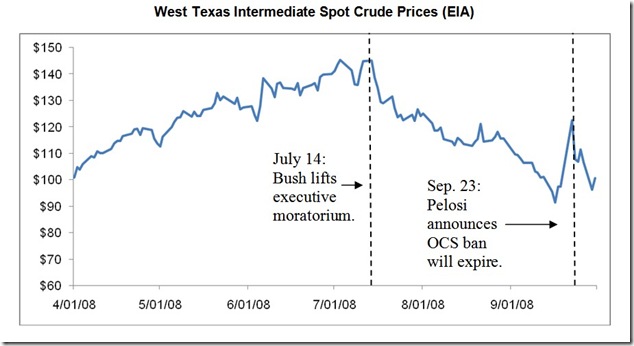

Second, in addition to the above Ivory Tower deep thoughts, we have this chart showing what happened to near-term oil futures prices when President George W. Bush in July 2008 removed just the Executive Branch moratorium on offshore drilling (which by itself had zero marginal effect) and then the Pelosi Congress allowed the Congressional moratorium on drilling in the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) to expire a few months later:

(This article gives the full context for the above chart.) As the chart above suggests, we economists need to start out with the Efficient Markets Hypothesis and Hotelling’s Rule on our blackboards, but I think we also need to realize that the real world apparently doesn’t work that way. So our job is to figure out exactly what is wrong with those elegant, baseline constructions, since the average Joe will say something like, “Well people aren’t rational.” I agree that that’s not a satisfactory refutation of the EMH, but something is sure screwy with it–or at least, with the conclusions that prominent economists draw from it.

Finally, a question for Steve: Suppose that the US government dropped a nuclear bomb on Iran, and that all politicians from both parties said they would continue this policy for years to come. If I understand your position, you would say that this could raise world oil prices temporarily, but only until (say) other, existing well operators could expand output? So maybe by 2016 you think that world oil prices would be back to what they otherwise would have been, even if–in 2016–the US is still periodically nuking the Middle East, and at that time there is no likely presidential candidate who pledges to stop?

David Glasner Needs to Re-Read Mises

The mischievous von Pepe dangled a recent post by David Glasner in front of me. Glasner writes:

[T]he notion of unsustainability [in Austrian business cycle theory] is itself unsustainable, or at the very least greatly exaggerated and misleading. Why must the credit expansion that produced the interest-rate distortion or the price bubble come to an end? Well, if one goes back to the original sources for the Austrian theory, namely Mises’s 1912 book The Theory of Money and Credit and Hayek’s 1929 book Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, one finds that the effective cause of the contraction of credit is not a physical constraint on the availability of resources with which to complete the investments and support lengthened production processes, but the willingness of the central bank to tolerate a decline in its gold holdings. It is quite a stretch to equate the demand of the central bank for a certain level of gold reserves with a barrier that renders the completion of investment projects and the operation of lengthened production processes impossible, which is how Austrian writers, fond of telling stories about what happens when someone tries to build a house without having the materials required for its completion, try to explain what “unsustainability” means.

The original Austrian theory of the business cycle was thus a theory specific to the historical conditions associated with classical gold standard.

I really don’t understand how Glasner could have written the part I put in bold. Of course Mises wrote that the boom is indeed unsustainable; he was the one who used the analogy of the master builder running out of bricks in Human Action.

Worse for Glasner, in the Theory of Money and Credit itself, Mises is crystal clear that he rejects Glasner’s interpretation above. Here is a beautiful statement: “Painful consideration of the question whether fiduciary media really could be indefinitely augmented without awakening the mistrust of the public would be not only supererogatory, but otiose.” That’s really all you need, but in case it’s not clear, let me spell it out more with further quotes:

The situation is as follows: despite the fact that there has been no increase of intermediate products and there is no possibility of lengthening the average period of production, a rate of interest is established in the loan market which corresponds to a longer period of production; and so, although it is in the last resort inadmissible and impracticable, a lengthening of the period of production promises for the time to be profitable. But there cannot be the slightest doubt as to where this will lead. A time must necessarily come when the means of subsistence available for consumption are all used up although the capital goods employed in production have not yet been transformed into consumption goods. This time must come all the more quickly inasmuch as the fall in the rate of interest weakens the motive for saving and so slows up the rate of accumula- tion of capital. The means of subsistence will prove insufficient to maintain the labourers during the whole period of the process of production that has been entered upon. Since production and consumption are continuous, so that every day new processes of production are started upon and others completed, this situation does not imperil human existence by suddenly manifesting itself as a complete lack of consumption goods; it is merely expressed in a reduction of the quantity of goods available for consumption and a consequent restriction of consumption. The market prices of consumption goods rise and those of production goods fall.

And just to make it crystal clear, Mises devotes–literally–an entire section at the end of his chapter on the trade cycle to make sure no one walks away with Glasner’s interpretation. An excerpt:

If our doctrine of crises is to be applied to more recent history, then it must be observed that the banks have never gone as far as they might in extending credit and expanding the issue of fiduciary media. They have always left off long before reaching this limit, whether because of growing uneasiness on their own part and on the part of all those who had not forgotten the earlier crises, or whether because they had to defer to legislative regulations con- cerning the maximum circulation of fiduciary media. And so the crises broke out before they need have broken out. It is only in this sense that we can interpret the statement that it is apparently true after all to say that restriction of loans is the cause of economic crises, or at least their immediate impulse; that if the banks would only go on reducing the rate of interest on loans they could continue to postpone the collapse of the market. If the stress is laid upon the word postpone, then this line of argument can be assented to without more ado. Certainly, the banks would be able to postpone the collapse; but nevertheless, as has been shown, the moment must even- tually come when no further extension of the circulation of fiduciary media is possible. Then the catastrophe occurs, and its conse- quences are the worse…

Of course, Mises could be totally wrong here; but Glasner is wildly off the mark when he says Mises (and Hayek) only presented a theory of crises applicable to the gold standard era.

Here is the Theory of Money and Credit, and here’s my study guide to it.

Yet Another (More Informed) Plug for Tom Woods’ Liberty Classroom

And here’s the link to fund the Murphy Christmas Initiative.

A True Example of Christian Humility

For today’s post I just want to relay something that blew me away from the sermon one of the assistant pastors gave at my church today. He was talking about the following passages from Luke:

Chapter 20…

45 Then, in the hearing of all the people, He said to His disciples, 46 “Beware of the scribes, who desire to go around in long robes, love greetings in the marketplaces, the best seats in the synagogues, and the best places at feasts, 47 who devour widows’ houses, and for a pretense make long prayers. These will receive greater condemnation.”Chapter 21

And He looked up and saw the rich putting their gifts into the treasury, 2 and He saw also a certain poor widow putting in two mites. 3 So He said, “Truly I say to you that this poor widow has put in more than all; 4 for all these out of their abundance have put in offerings for God,[a] but she out of her poverty put in all the livelihood that she had.”

So if I’ve made it clear in the above, what happens is that there is a chapter break (from 20 to 21) where many New Testament scholars think that there shouldn’t be. Our pastor said something like the following:

Now what happens though is that some preachers will skip the whole context of Jesus arguing with the scribes in the Temple, and instead they’ll go right to Chapter 21 and the widow with her two mites. How many of you–show of hands–have heard a sermon just on the widow putting in her two mites? [Pause.] Yes, a lot of you. When you heard those sermons, what was the punchline? Ha ha, I see someone in the front row stuck his hand out–that’s right, they’re asking for money!

Now I went on google and pulled up lots of sermons doing just this. In fact, let me read from one of them. Now here I’m quoting the conclusion from this pastor who had derived ‘five Biblical principles of giving’ from this story. After listing the principles he concluded, ‘And so we all must have the attitude of the widow if we’re going to build this new facility.’

Now it wasn’t as if there was an audible gasp in the crowd or anything, but I personally–in the way this guy had built up to this part of his sermon today–was disappointed in the guy he was quoting. I had no problem with someone trying to derive lessons about giving from just the four verses in Chapter 21 (as opposed to tying it back to the widows being discussed at the tail end of Chapter 20), but I definitely thought it was a little gauche for the quoted preacher to tie it specifically to a facility that they were building and for which he was apparently raising funds that very day from his congregation.

So you can imagine my shock when my pastor today continued:

Now folks, I am not here to tell you that all of these other preachers were ‘wrong.’ I’m merely saying that where I stand today, that’s not what I believe Jesus was getting at in His remarks about the widow giving her two mites. I don’t agree with the interpretation given by the preacher I just quoted. And do you know who that preacher was? It was me, and I gave that sermon to all of you, back in December 1999 when we were building our new school. So do pastors ever have ulterior motives for what they preach on Sunday? Yes I guess we do.

I still can’t believe he said that.

Recent Comments