Gene Callahan and Abba Lerner Insist on Plain English in the Debt Debate

After my Rodney King-ish post trying to say we’ve all been groping around this complex issue, Gene Callahan announces that Abba Lerner was right all along, and that Nick Rowe has just been playing a verbal trick. Lerner says that if we use plain English, it is obvious that government debt can’t burden future generations.

In light of this new post, and Gene’s statement of his overall stance on this issue, I went to the local mafia boss near Gene’s place in Brooklyn. I grew out my beard, and got a fake driver’s license that said “Gene Callahan.” Then I took $15,000 from the mafia boss, and signed an official affidavit saying, “I, Gene Callahan, grant the holder of this note authority to take ownership of my car.”

After blowing the $15 grand at the casino, I swung by Gene’s apartment. The following conversation ensued:

GENE: You did what?!

BOB: Not sure why you’re getting so upset. I haven’t hurt you in any way, shape, or form, unless you adopt some weird definition of “hurt.”

GENE: You just enjoyed a rip-roaring binge at the casino by issuing a claim on my property, without even consulting me.

BOB: What’s your point? I’m not following you here. I had a great time. You don’t like me to have fun?

GENE: Tony and Luigi are coming here right now to take my car!!

BOB: Yep, that will probably suck.

GENE: It’s your fault they’re coming!

BOB: What are you talking about? All I did was sign a piece of paper and take their money. They’re the ones who are going to physically take your car.

GENE: Because of you!!

BOB: I can see you’re not a philosopher. My signing that paper and taking their money was neither necessary nor sufficient for you to lose your car. It wasn’t sufficient, because maybe you can talk them into just eating that $15,000 they gave me, and tearing up the note I signed. And it wasn’t necessary, because if they heard the things you say about Italians, they would’ve taken your car just for that, with no note from me. And anyway, maybe they’ll use your car to take you to the hospital when you fall and break your neck. You wouldn’t have been able to drive yourself in that scenario, and you’ll be really glad they took possession of your car at that point. Anyway, I really don’t see why you keep telling everybody, “Bob imposed a burden on me.” I didn’t do a thing to make you poorer, at least not if we’re using plain English. Go ask your Brooklyn buddies. They’ll surely agree with me that you are directing your ire at the wrong person.

Debt Burdens: How Deep the Rabbit Hole Goes

You guys aren’t going to believe it, but I have had another epiphany. The debt and future generations issue is like this:

At first I was deeply troubled, because I realized that I had said at least two false things in my arguments with Ken B. today, and that I had unfairly dismissed a point that “stickman” and Daniel Kuehn had brought up.

But now that I have achieved a higher level of consciousness, I don’t care. All of God’s children have added something to this fascinating issue. I need to let it sink in over the weekend. Next week I will have lots of pretty Excel examples to illustrate everything.

I know, some of you would go insane if I left you hanging for three days in agony. Here’s a hint, a comment I left at Nick Rowe’s blog:

Lord, I agree with you that it’s not just the servicing of the debt, but paying the debt down, that is the crucial thing.

Nick, you aren’t going to believe this, but I’m taking a giant step toward the MMT camp on this. Before, I thought the issue was future generations being taxed to service the debt, but now I’m thinking the only way you make them poorer on net is if the taxes to deal with the debt are higher than the interest payments to the debtholders. So that means, only if the debt is shrinking. In the examples I cooked up–and I think you too?–the way you make everybody alive in period X poorer, is you have net debt reduction. I think if middle generations just floated the debt without moving it up or down, then they break even collectively.

Gasp, dare I say it, they break even because they are paying the interest to themselves? Real GDP is unaffected so total income is unaffected?

I am not going to do a formal post until Monday, Nick, so if you think I’m being seduced by the Dark Side you have the weekend to save me…

Four last points for now:

==(1)==> If I’m thinking about this correctly (a big if, since I was doing this in my head while getting ripped at the gym), it really is the creation of new government debt that allows the present generation to enrich itself at the expense of “people in the future” collectively, but if you never pay down the debt, then that impoverishment is indefinitely postponed.

==(2)==> Those of you who have been telling me, “Bob, what the )#(*%$39 is your problem, stop doing flow analyses, do it in terms of balance sheets! Then it’s obvious that government debt PER SE makes future generations poorer,”… all I can say is, at least I admit when I should have listened to you sooner.

==(3)==> Once you get your head wrapped around the above, take it even further and ask yourself: Why wouldn’t the immediate generation automatically push itself to the debt limit? Why might it, for example, even run a budget surplus and hand that down to its descendants? (Here’s a hint: Suppose we still have an apple endowment economy, but the harvests are really good some years and awful other years. Throw in a modicum of altruism for the next generation. Now ask yourself whether Krugman has been “basically right” on this…)

==(4)==> You guys work on this with the TA until I get back. I have to go to the karaoke bar and practice for Tatianna’s visit in two weeks…

At Least This Guy Appreciates Me

In contrast to jokers to the left of me and clowns to the right, this guy understands me:

Shocker! Perhaps the Debt Burden Is Really About Future Taxes…?

Yes I’m being saucy, but Daniel in the comments just wrote this: “I am more curious right now how to take Grant’s point that what changes things is the taxes, not the debt. It only hurts future generations when you change the financing scheme.”

Everyone, let’s take a deep breath. Of course that’s what makes future generations poorer. Go read the words I put in Landsburg’s mouth in “The Economist Zone.” I had him make this point beatifully and with pizzazz, in a way that started David Brooks on the path to you-know-what.

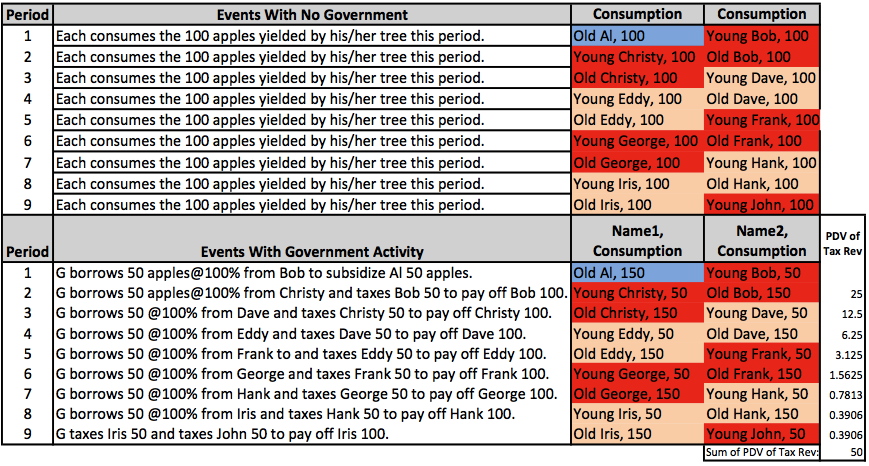

Then, recall this adapted Excel table I posted for all of you back on January 9, 2012, along with my commentary on it:

Everyone see how this one plays out? In period 1, Old Al clearly benefits. He gets a government transfer of 50 apples, paid for by a government budget deficit (there is no taxation in period 1).

Also note that I’ve put in the PDV of the tax receipts at each period. See how they sum up to 50 by the end? So one way to understand what is happening, is that the government gives Old Al a payment of 50 apples in period 1, and then spreads the tax burden to pay for it over everybody else (at some point in their lives) in periods 2 through 9. The government uses the bond market to pull all of that revenue forward in time, and give it as a spot payment to Al in period 1.

Now the crucial thing about this particular example I’ve constructed, is that Old Al is the only person who benefits from it, while every other single human being in the country, forever and ever and ever loses in this scenario. And yet, it is still the case that if we take any future time period, the “income earned by our descendants in period x is still 200 apples total.”

…

And in light of the above diagram, I would like Daniel to reconcile it with his frequently stated position: “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.”

Notice that Young Daniel Kuehn was annoying Young Bob Murphy even back then…

Generations vs. GDP

Yes, I have much more to say on the debt debate, not least because Dean Baker chimed in on a previous post (linking to his latest). I am waiting for clarification on his attempt to ballpark the empirical significance of the Nick Rowe Effect, and once I’m sure what Baker is saying, I will either pat him on the back or pounce. (My hunch is, I will pounce.)

For right now, just another quick clarification. Daniel Kuehn has been the champion of this view, but I think others believe it too, and going over it will in any event (I hope) make things easier for everyone who still cares…

Daniel has claimed all along that Krugman was *merely* claiming that government debt can’t reduce future GDP. Daniel thinks that Nick Rowe and I “moved the goalposts” by talking about future Americans, and that there is mushiness in the term “future generations.” Some of my thoughts:

==(1)==> Neither Nick nor I ever claimed that government debt (if we rule out the disincentives from taxes, crowding out, etc.) per se would make real output lower in the year 2100. Indeed, we deliberately constructed our examples to have a constant GDP, just to make sure that issue wasn’t throwing anybody.

==(2)==> What Nick and I *did* claim was that Paul Krugman and Dean Baker were leaping from this correct proposition, to the FALSE conclusion that “Americans in the future” couldn’t be made poorer because of government debt. After all, this is an easy thing to conflate. Look at this:

TRUE STATEMENT: Government debt (under the conditions we take for granted in this debate) can’t reduce the total after-tax income that Americans earn in the year 2080 and beyond.

FALSE STATEMENT: Government debt (under the conditions we take for granted in this debate) can’t reduce the total lifetime after-tax income earned by Americans living in the year 2080 and beyond.

==(3)==> If it is pointed out to any pundit or American voter who is interested in this debate, that our deficits today might make every single American born after 2013 poorer, but that US real GDP from 2013 onward will remain unaffected, then 99.9% of the people hearing this will agree that the former effect is the relevant one for our policy debate. Nobody cares about future GDP per se, except insofar as it has relevance for Americans who will be alive in the future. (Well, Scott Sumner might care about future GDP more than future human beings, but that’s about it.)

==(4)==> Daniel surely thought he had a smoking gun in his favor when Paul Krugman recently wrote this:

[L]et me suggest that the phrasing in terms of “future generations” can easily become a trap. It’s quite possible that debt can raise the consumption of one generation and reduce the consumption of the next generation during the period when members of both generations are still alive. Suppose that after the 2016 election President Santorum tries to buy senior support by giving every American over 65 a gift of newly printed government bonds; then the over-65 generation will be made richer, and everyone under 65 will be made poorer (duh).

But that’s not what people mean when they speak about the burden of the debt on future generations; what they mean is that America as a whole will be poorer, just as a family that runs up debt is poorer thereafter. Does this make any sense? [Emphasis in ORIGINAL.]

Now I bet Daniel saw that and said, “Aha! I knew it! Krugman is here saying in crystal clear language that he knew all along that every single American born in 2013 and later, could be made poorer by our deficits today. All Krugman was telling his readers was that the important thing was that real GDP would still be OK, from 2013 onward. It’s hard work being so awesome.”

Nope Daniel (if that’s what you thought), that’s not what just happened there. Here’s what happened:

Krugman all along has thought that “Americans collectively in the future” was interchangeable with “real output in the future.” So yes, he phrased some of his arguments in terms of real GDP, not because he thought real GDP was more important than our grandkids, but rather because he thought our grandkids couldn’t possibly be hurt so long as real GDP was the same as it otherwise would have been, during every single year in which our grandkids are alive. I mean re-read what I just typed out: This is a very natural thing to believe. Only with the screwy overlapping generations thing, does this “shortcut” fall apart.

So now, Krugman is bothered by this Nick Rowe guy, a little Canadian gnat who won’t go away. Krugman ignored him back in January 2012, but man this guy just keeps buzzing around his ear, so Krugman finally breaks down and quickly skims some of this deficit-phobe’s posts.

Now because Nick for some inexplicable reason prefers to type out 4 dense paragraphs of text describing an apple economy involving *only* 3 generations–rather than just reproducing my beautiful Excel table showing the phenomenon over 10 generations, where the first 5 all gain and the last 5 all lose–Krugman didn’t see the big picture. Instead, Krugman thought Nick was truly playing a trick with the word “generation.”

Remember, Krugman all along has been thinking that since real GDP in the year 2080 can’t be reduced, then it can’t possibly be the case that Americans “as a whole” alive in 2080 can be hurt. Sure, if the government takes a billion from some Americans in 2080 those Americans will be poorer, but then when the government gives it to some OTHER Americans in 2080, those Americans will be that much richer, dollar-for-dollar, and the whole thing is a wash. Thus, since real GDP in 2080 is unaffected, Krugman thinks interest payments on debt can’t possibly make “America as a whole” poorer in 2080. One way Krugman describes this, is to say the debt can’t make “future generations as a whole” poorer.

Ah, but now this little stinker Nick Rowe comes along. To repeat, Krugman skims Nick’s posts, and then thinks this is the trick: Nick is simply showing that one generation can make “the next generation” poorer if the impoverishment happens while they’re both alive.

So, Krugman thinks, “Oh my gosh this is so stupid. I know real GDP in 2080 can’t be reduced by debt. So as a shortcut I have said, ‘Future generations of Americans can’t be hurt by debt.’ But now this hustler Nick Rowe is pointing out that it’s theoretically possible in the year 2080 that all of our grandkids could extract a trillion dollar interest payment from all of our great-grandkids, who are alive in 2080 too. So in that sense, Nick thinks he just showed that a future generation–namely, all of our great-grandkids–were made poorer by the scheme. But give me a break, it’s still true, as I’ve always said, that the group ‘Americans alive in 2080’ are just as well off as if the debt were $0. Somebody shoot this guy.”

Does everybody see that? Go read Krugman’s quotation above about the “trap.” See how my interpretation perfectly explains what he’s writing here, whereas Scott Sumner’s interpretation makes no sense?

Last point I want to make to all of you who have been defending Krugman, and I especially include Daniel Kuehn, who thinks Krugman is today’s Bastiat: Isn’t it odd that Paul Krugman, who is normally so crystal clear in his writing, keeps going off on total non sequiturs, and keeps leaving it up to you guys to explain “what he’s really been trying to say” on this debt stuff? Isn’t the more plausible explanation that my interpretation of his position is correct, since every point coming out of his blog fits my interpretation perfectly?

In other words, if Krugman is thinking about it the way I claim he is, then he has been writing crystal clearly on this thing all along. However, if Krugman has merely been trying to say that it’s transfer payments that make future generations poorer (like Gene Callahan said), or that Krugman agrees that debt owed to foreigners is benign (like Landsburg said), or that debt can make all future Americans poorer but not future GDP (like Daniel says)…then he has been unbelievably unclear all along. Why doesn’t he just come out and say those things? Why rely on thought experiments about presidents suddenly issuing bonds etc., that make absolutely no sense if his position all along has been what you guys claim?

A Post on Debt Burdens for the Masses

I devoted my American Conservative column this time to everyone’s favorite question. For what it’s worth, I think this is the most succinct explanation I’ve given yet. Some key excerpts:

What Baker and Krugman want to explode is the man-on-the-street’s moralistic objection to government budget deficits as being irresponsible and a burden on future generations, who will have to deal with higher government debt. Baker and Krugman think that this is yet another example of where “micro” thinking breaks down when we try to aggregate it into the “macro” economy. They concede that it makes sense for an individual householdto worry about irresponsibly running up debts today, and thereby imposing pain in the future when those debts have to be paid off—or at least, when more of the household’s income needs to be devoted to interest payments on the higher debt.

However, so long as future Americans end up holding the Treasury bonds issued by Uncle Sam, Baker and Krugman think that our generation cannot irresponsibly run up the debt today, and pass on a burden to our kids and grandkids. The difference arises (they claim) because all of the interest payments (mostly) stay within America, to the extent that “we owe it to ourselves.” Sure, Baker and Krugman admit that some of the U.S. federal debt ends up being held by foreigners, and to that extent our grandkids will be poorer because they’ll have to make interest payments flowing out of the country. But besides this complication, Baker and Krugman argue that the mere fact of taxing and paying interest on bonds per se can’t burden our grandkids, since (some of) our grandkids will be the ones pocketing the interest payments!

…

Suppose the government today borrows an extra $100 billion in order to expand drug coverage for seniors. Assume that the young workers today “pay for it” in the direct sense that they reduce their consumption by $100 billion, in order to invest in the additional $100 billion in government debt that has to be issued. (Thus, we are assuming unrealistically, for the sake of argument, that the higher government debt doesn’t “crowd out” private investment, just so we can see quite clearly why Baker and Krugman are wrong on this issue.) Clearly the older folks are better off because of this deal: they get more drug coverage from government spending, and don’t have to pay higher taxes to finance it.Now further suppose that the young workers don’t touch their bonds, which happened to be 30-year Treasury securities rolling over at (say) 3 percent. After 29 years have passed, the originally young workers are now old. The original seniors—the ones who benefited from the $100 billion in extra drug coverage—are long dead. A new group of workers—who weren’t even alive when the $100 billion was borrowed—are now on the scene.

The now-old retirees sell their 29-year-old bonds at their current market value of $236 billion (that’s the original $100 billion compounding at 3 percent annually for 29 years in a row). At this point, the middle generation—the ones who were young workers originally, and now are retiring and living off of their savings—have been made whole. Yes, they reduced their consumption by $100 billion back when the government ran a budget deficit, but at the time they voluntarily lent that $100 billion to the government, because they thought getting $236 billion in 29 years when they were retiring would make the whole deal worthwhile. They didn’t lose from the whole operation.

Finally, suppose that the young workers (who were recently born) hold on to their government bonds for one more year, when they mature with a market value of $243 billion. In order to pay off the bonds, the government imposes a one-time surtax on current workers of exactly $243 billion. It thus takes the money out of the workers’ paychecks, and then hands it right back to them to redeem the 30-year bonds that they are holding.

The way Dean Baker and Paul Krugman have been “educating” their readers since late 2011 on this issue, they would be forced to argue that in our story above, the young workers weren’t hurt by the original $100 billion borrow-and-spend scheme. After all, the government 30 years later simply took $243 billion from those workers, and then gave it right back to them. So clearly it’s a wash, right?

But we can see it obviously wasn’t a wash. The original, old generation benefited greatly, the middle generation did all right, and the young generation—not even alive at the time of the original $100 billion deficit—got skewered. Yes, they “owed the federal debt to themselves,” but that is hardly consolation to them. They acquired the bonds by reducing their consumption by $236 billion the year before the big tax bill hit. This abstinence was not rewarded with additional consumption at some future point, but instead was necessary just to break even after the government whacked them with a big tax bill to retire its exponentially rising debt.

A Challenge on the Great Debt Debate

Here’s a challenge I gave to Daniel Kuehn in his comments:

==> Do you agree that Krugman said there is a sense in which debt makes a household or a family poorer? But that he denied this truth for the individual family could be aggregated to the USA as a whole?

==> If you agree with the above, give me a specific numerical example of what it means for a family to be made poorer in the future by running up a debt today. Then, defy me to show you in my apple examples what this would look like, at the USA level. In other words tell me what it would mean if Krugman were wrong, and that the USA *could* be made poorer in the future because of running up the debt today, in the same way that Krugman agrees could happen with an individual family. So then you tell me, “Bob, if Krugman were wrong, then you would be able to construct an apple scenario showing such-and-such. But it impossible for you to do so. If you *could* do so, I would agree you have been right and Krugman’s narrow point is wrong, and we need other arguments to justify deficits today.”

As is his wont, Daniel denied that Krugman said debt could make a family poorer in the future. To bolster my understanding that Krugman thinks debt *does* make an individual family poorer in the future, here are two quotes from him:

People think of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of money you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt we create is basically money we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.

And for the coup de grace:

But that’s not what people mean when they speak about the burden of the debt on future generations; what they mean is that America as a whole will be poorer, just as a family that runs up debt is poorer thereafter. Does this make any sense?

OK everybody? So I want you all to show me a specific numerical example in which you agree that a family *does* make itself poorer in the future, because it ran up a debt today. Then, tell me specifically what it would look like in my apple model, for “the nation” to do the same thing, and why it would be impossible for me to actually construct such an example.

Scott Sumner Confirms My Own Hypothesis

Quick question everybody: Suppose a man were insane. What would the world look like from his perspective?

OK, perhaps apropos, here’s Scott Sumner today: “My working hypothesis for the last four years has been that the entire world went insane on or about Oct 1st 2008.”

Recent Comments