If Bryan Caplan Had His Way, We Would Never Have Heard of David Henderson

Bryan Caplan argues that because most people don’t remember or use algebra as adults, it fails a cost-benefit test and shouldn’t be taught. Bryan acknowledges that people who go on to take calculus retain their knowledge of algebra even into adulthood, but doesn’t draw the obvious inference–that people with mathematical aptitude first take algebra, and then gladly go into the harder stuff.

What amazes me is that Bryan doesn’t even give a nod to what (in my mind) is the most obvious reason to continue to teaching algebra to everybody: We are casting a wide net to ensure that we steer the right people into areas where their minds will do the most good. People like David R. Henderson. Had he not been exposed to algebra and its delights, DRH might be a retired hockey player right now, promoting his autobiographical The Joy of Checking.

It’s On: Murphy-Sumner Debate Begins in January 2013

Holy cow, I totally forgot to announce the news: I proposed to Scott Sumner that instead of a live video debate, instead we have a 3-part exchange. Each month, I will write a 2000 – 2500 word blog post challenging his views on NGDP targeting, to which he will respond with whatever length he desires. Presumably his commenters and you guys will be chiming in on our respective posts, so that by Round 2 my 2000 – 2500 word post will gain from everybody’s input.

Scott agreed, but said he couldn’t start until January. (Oh, as an added sweetener, I got Major Freedom to agree that he wouldn’t post on Scott’s blog for the entire three months of the debate. I’m not even kidding.)

I must admit I’m a bit nervous, but someone has to stand up to this guy before he takes over.

Why Dean Baker and Paul Krugman Were Wrong on the Debt Burden for At Least 11 Months

By this point, those of you who have been reading Free Advice should understand exactly what Don Boudreaux and Nick Rowe were saying, when Dean Baker and then Paul Krugman last year first started up the Great Debt Debate. What is still extremely interesting to me personally, is how many economics bloggers have concluded that Krugman was essentially right all along. No, he wasn’t, and that’s what I’m going to demonstrate in this post.

Before embarking on this thankless task, a disclaimer: This isn’t merely because I’m out to get Krugman, though I must admit that’s probably part of the impetus. Rather, since so many people to this day can’t see how clearly and obviously Krugman’s writing on this–from the get-go and including his latest post–is based on a fundamental mistake, it makes me suspect that these people never really understood the controversy. Therefore it’s worthwhile, I hope, to walk through this stuff at least once more from first principles, to get you guys to see the specific argument Baker and Krugman were making–their essential “insight” into why the federal debt can’t burden future Americans–so that you will then more fully appreciate why Nick Rowe picked the specific counterexample that he did. (Inconceivably, we still have critics complaining that our counterexamples are “totally rigged to show a burden.” Yes my friend, that’s how counterexamples work! You deliberately calibrate them to show your opponent has made a false general statement. My goodness this debate has been exhausting.)

First off, Krugman and Baker both admit that there is a sense in which private debt can burden a household in the future. They are simply denying that this “micro” insight can be aggregated to the macroeconomy as a whole. In other words, they claim there is a fallacy of composition going on. Just to make sure you believe me, here is Krugman on December 28, 2011:

People think of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of money you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt we create is basically money we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.

And just to make sure you believe me when I say Krugman’s position has not budged one iota in this entire debate, here is Krugman on October 12, 2012 (after he explicitly acknowledged Nick Rowe’s role in this):

[L]et me suggest that the phrasing in terms of “future generations” can easily become a trap. It’s quite possible that debt can raise the consumption of one generation and reduce the consumption of the next generation during the period when members of both generations are still alive….

But that’s not what people mean when they speak about the burden of the debt on future generations; what they mean is that America as a whole will be poorer, just as a family that runs up debt is poorer thereafter. Does this make any sense?

OK, does every see this? Krugman admits that for an individual household, yes of course debt can impose a burden in the future–the household has to make interest payments that “go out the door.” But this micro logic breaks down, Krugman believes, when you aggregate it to the country as a whole. This is because one American household’s interest payment on the federal debt, goes into the pocket of some other American household that is holding the Treasury bond. So the wealth stays within the household, when “the household” is the USA.

Now that you see this is the essential “insight” that Krugman and Baker were making, you can understand why they laid so much stress upon whether Americans versus foreigners would be holding the debt in (say) the year 2100. Look guys: Krugman made the title of his inaugural blog post “Debt Is (Mostly) Money We Owe to Ourselves.”

Why did Krugman and Baker lay so much emphasis on Americans vs. foreigners owning the government debt–why did they in fact base their entire case on it? They did so because their argument for the non-burden of debt totally breaks down if our grandkids have to make interest payments to foreigners in 2100. But so long as the American taxpayers in 2100 are making interest payments to American Treasury holders in 2100, they think it’s a wash, and that we can’t possibly be burdening them. As Baker himself said on December 27, 2011, in the post that set the blogosphere on fire:

As a country we cannot impose huge debt burdens on our children. It is impossible, at least if we are referring to government debt. The reason is simple: at one point we will all be dead. That means that the ownership of our debt will be passed on to our children. If we have some huge thousand trillion dollar debt that is owed to our children, then how have we imposed a burden on them? There is a distributional issue — Bill Gates’ children may own all the debt — but that is within generations, not between generations…

One can make the point that much of the debt is owned by foreigners, but this is a result of our trade deficit, which is in turn caused by the over-valued dollar.[Emphasis in original.]

So now you see the power of Nick Rowe’s original counterexample (and my elaboration with purdy pictures). We are showing that this “insight”–that private debt can be a burden, since you are making payments that leave the household, while public debt can’t possibly be a burden, since Americans are just paying other Americans–is wrong. In our little models, there are no foreigners; the debt is always “owed to ourselves” in that little economy, and yet clearly the future taxes needed to pay down the debt impose a net burden per capita on everybody alive at that time. It’s not a wash, a mere hurting off one grandkid with a simultaneous and equal helping of another grandkid, at least not in the way Krugman and Baker have been leading their readers to believe.

One last major point here: Notice how my interpretation of Krugman and Baker’s position, can explain all of their writings throughout this debate. I can explain why they concede private debt is burdensome, while public debt is not, so long as Americans in the future end up holding the Treasury bonds. In contrast:

==> Steve Landsburg says Krugman is right in one respect, but wrong because (Landsburg claims) Krugman forgot to make the point that it’s irrelevant whether Chinese or Americans hold the bonds. No, Steve, as Krugman’s very post title indicates, Krugman thinks it does matter. He didn’t forget to make what you consider to be the essential point; Krugman doesn’t see the essential point.

==> Gene Callahan is wrong for thinking Krugman has merely been talking about the net transfer payments being the burden. If that were the case, Gene, then Krugman would think even private debt isn’t burdensome. After all, whatever the guy in the street thinks about “my credit card debt imposes a burden on me next month,” I can reproduce exactly the same thing by having someone mug the guy next month. Nope, if Krugman were exonerating public debt for the reason Gene claims, then Krugman wouldn’t have said public debt is fundamentally different from private debt.

==> Daniel Kuehn is wrong for thinking Krugman was only talking about real GDP, and not about future Americans. Private debt doesn’t lower my marginal productivity and paychecks in the future, either. So again, Krugman’s distinction between public and private debt would make no sense, if Kuehn is right.

==> Scott Sumner is wrong for thinking Krugman finally gets it with his discussion of Rowe. Nope: Krugman italicizes in the passage Scott quotes, the alleged importance of two generations being alive at the same time. That is clearly not needed in Rowe-type models, as my canonical example illustrates. Every single person alive in 2012, can enrich himself at the expense of every single person alive in 2112, using deficit finance and taxes levied for bond retirement in 2112. Krugman clearly doesn’t get it. If Sumner were right, Krugman wouldn’t have put in (and italicized!) the clause about the two generations needing to be alive at the same time for Nick’s “magic trick” to work.

In conclusion, my interpretation of Baker and Krugman perfectly explains their every move in this entire debate. In contrast, for Landsburg, Callahan, Kuehn, and Sumner:

Quotable Quote on Debt Burdens

It really clicked for me when I summarized my Freeman article this way:

If an imperialist government paid for popular spending programs by levying a tax not on its own citizens but on a conquered land, the scheme would of course be a gigantic theft working across space and through the currency markets. Deficit finance is similar, working across time and through the bond markets. It allows today’s citizens to pay for government goodies by levying a tax on unborn generations who have no say in the political decision.

Learn it, live it, love it.

Debt Burden: Old Murphy vs. Young Murphy

Just to warn you, kids, there are at least another 3 posts in me on this topic. But it’s all new stuff. It’s kind of like every time they came out with a new Matrix: It wasn’t nearly as exciting as the first one you viewed, but you had to keep watching to the bitter end so you didn’t miss anything possibly important.

“Senyoreconomist” in the comments said that he uses my Lessons for the Young Economist as a text, and since I keep saying I made a mistake in it, he understandably wants to know what to tell his poor students when they get to this part. So here is the relevant section, and I’m underlining the passages that are either flat-out wrong or at least very misleading, in the context in which I make them. Note the similarity to what Krugman and Dean Baker have been writing on this issue all along; I arguably have here spelled out their perspective more clearly than they themselves did:

Government Debt and Future Generations

In popular discussions, opponents of government deficits often claim that they represent theft from unborn generations. The idea is that if the government spends an extra $100 billion to make voters happy but without “paying for it” through raising taxes, then the present generation has gotten to enjoy an extra $100 billion whereas future taxpayers will have to bear the cost. Is this typical claim really right?

As with the popular association of government debt and inflation, the answer is nuanced: Yes government deficits do impoverish future generations, but no they don’t do so for the superficial reason that most people believe.

When thinking about any debt, be it government or private, keep in mind that all goods are produced out of present resources. There is no time machine by which people today can steal pizzas and DVDs out of the hands of people 50 years in the future. If the government spends an extra $100 billion to mail every voter a lump sum payment to go spend at the mall, it doesn’t matter whether the expenditure is financed through tax hikes or borrowing. Either way, it is the present generation (collectively) who pays for it.

Now of course, in practice there is a difference in how this burden is shared among the present generation, and that’s the whole reason that it’s popular to run budget deficits. If the government raised everyone’s taxes in order to send them all the money back in a check, that would be pointless. But if instead the government borrows $100 billion from a small group of investors and then mails this money out to everybody else, the average voter feels richer.

One way to see the fallacy in the standard “we’re living at the expense of our children” analysis is to realize that today’s investors bequeath their government bonds to their children. It is certainly true that higher government deficits today, mean that future Americans will suffer higher taxes (necessary to service and pay off the new government bonds). But by the same token, higher deficits today mean that future Americans will inherit more financial assets (those very same government bonds!) from their parents, which entitle them to streams of interest and principal payments.

So what does all this mean? Are massive government deficits really just a wash? No, they’re not. The critics are right: Government deficits do make future generations poorer. But the reasons are subtler than the obvious fact that higher debts today lead to higher interest payments in the future, since (as we just explained) those interest payments go right into the pockets of people in the future generations.

So here are [three] main reasons that government deficits make the country poorer in the long run:

==> Crowding out. When the government runs a budget deficit, the total demand for loanable funds shifts to the right. This pushes up the market interest rate, which causes some people to save more (moving along the supply curve of loanable funds) but also means that other borrowers end up with less. In effect, the government competes with other potential borrowers for the scarce funds available. Economists say the government borrowing crowds out private investment. At the higher interest rate, entrepreneurs invest fewer resources into making new factories, buying more equipment, etc. So long as we make the very plausible assumption that the government will not use the borrowed money as productively as private borrowers would have, it means that future generations inherit an economy with fewer factories, less equipment, and so on. This is a major factor in explaining why government deficits translate into a poorer future.

==> Government transfers are a negative-sum game. Another way that government debt makes future generations poorer is through the harmful incentive effects of the future taxes needed to service the debt. For example, if the government runs a deficit today, and needs to pay back $100 billion to creditors in 30 years, that does indeed make the country poorer at that time. But the problem is not the $100 billion payment per se—that comes out of the pockets of taxpayers, and goes into the pockets of the people who inherited the government bonds. Rather, the problem is that in order to raise the $100 billion, the government would probably raise taxes (rather than cut its spending), and this action would cause dislocations to the economy over and above the simple extraction of revenue.

==> The option of borrowing leads to higher spending. Yet another danger of government deficits is that they tempt the government into spending more than it otherwise would. Recall from Lesson 18 that all government spending, no matter how it is financed, siphons scarce resources away from entrepreneurs and directs them into channels picked by government officials. Because the public typically resists new government spending less vigorously when it is paid for through higher deficits, the possibility of issuing government bonds leads to higher government spending (and hence more resource misallocation, compared to the pure market outcome) than would occur if the government were forced to always run a balanced budget.

So we see that government deficits really do make everyone poorer (on average), but the mechanisms are subtler than the simple increase in the amount of money the federal government owes to various creditors.

Now the good news is, there’s not that much to “fix.” I still agree with the reasons I’ve given above for possible mechanisms through which government deficits today, can impoverish our grandkids. However, in writing the above I was wrong to imply that the man on the street’s intuition is off. I thought (before Nick Rowe freed me) that the mere fact that our grandkids would be paying higher taxes to finance debt payments couldn’t make our grandkids poorer, since they would just be “paying themselves.” What I failed to see was that they won’t necessarily inherit the bonds as a bequest, but they might have to reduce their consumption earlier in their lives in order to acquire the bonds from the prior owners. That’s what I overlooked, and it’s why I ended up (erroneously) criticizing the man on the street’s hostility to deficit finance.

To correct this problem, all you need to do is give your students my Freeman article, which fills the gap and gives a nice little thought experiment to show how–even if we ignore the other mechanisms–there really is a sense in which deficit finance allows the present generation to “pass the bill” on to future generations.

Murphy Talks to Yukon Boys About Anarchy

I am going to be on the Gadsen Rising show–which I believe is out of Alaska–from 4:30pm – 5:30pm Eastern time. I think they want to talk about private law and defense. You can stream it here.

Tatianna Has a Special Request for YOU

For realz, come to Nashville on November 3. In fact, come the day before–Friday November 2, as I will be organizing a special karaoke outing. All the cool kids are doing it.

A Post on Debt Burdens for Professional Economists

OK I gather that most people are moving on with their lives, so I’d better make this post now on everyone’s favorite question, “Does the government’s debt impose a burden on our grandchildren?” In this post, I want to explain why, as of Friday October 12, and after Nick Rowe went head-to-head against Brad DeLong, both Dean Baker and Paul Krugman were still saying false things. It was clear that they hadn’t yet fully removed themselves from their erroneous way of thinking about the issue–an erroneous way that I myself used to believe–even though they had now officially read what Nick Rowe had to say about the matter.

Here’s Krugman:

First, however, let me suggest that the phrasing in terms of “future generations” can easily become a trap. It’s quite possible that debt can raise the consumption of one generation and reduce the consumption of the next generation during the period when members of both generations are still alive. Suppose that after the 2016 election President Santorum tries to buy senior support by giving every American over 65 a gift of newly printed government bonds; then the over-65 generation will be made richer, and everyone under 65 will be made poorer (duh).

But that’s not what people mean when they speak about the burden of the debt on future generations; what they mean is that America as a whole will be poorer, just as a family that runs up debt is poorer thereafter. Does this make any sense?

…

[A] debt inherited from the past is, in effect, simply a rule requiring that one group of people — the people who didn’t inherit bonds from their parents — make a transfer to another group, the people who did. It has distributional effects, but it does not in any direct sense make the country poorer. [Emphasis in original.]

And now for Dean Baker:

I saw that Nick Rowe was unhappy that I was saying that the government debt is not a burden to future generations since they will also own the debt as an asset….The burden of the debt only exists if there is reason to believe that debt is somehow displacing investment in private capital, which is certainly not true at present.

As the above quotations clearly indicate, Krugman still thinks this is merely a distributional issue such that (say) some people alive in 2080 can be made poorer, but others must necessarily be made richer, by the level of interest payments that the government makes in 2080; yet clearly (so Krugman still thinks as of the above post on October 12) the country as a whole in 2080 can’t be made poorer by our debt decisions today, so right-wingers are nuts for worrying about us living irresponsibly at the expense of our grandchildren.

Dean Baker, for his part, thinks that debt payments per se can’t be a burden, since some people are being taxed while others (alive at the same time) are pocketing the tax revenues; it’s just a transfer payment at that future date. The only way our deficits today can hurt our grandkids, is if it somehow leads us to bequeath fewer tractors and drill presses to them.

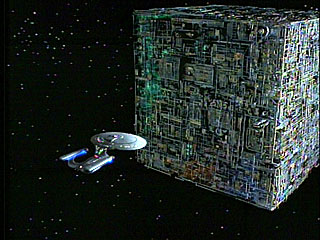

The following simple counterexample shows that each of these points is wrong. It is an elaboration of the text descriptions Nick Rowe has been dreaming up, but it is better pedagogically because (a) you can “see it” in one fell swoop, and (b) it has more than 3 generations, making sure Krugman and Baker can’t get by with thinking this is still just an intra-annual redistribution that can’t make “future generations” poorer collectively.

So here’s the picture, and then I’ll explain to professional economists (and others who are comfortable with mathematical economic models) how to parse it:

The above depicts a pure endowment economy. Each period, 200 apples are produced; that is “real output” and it is technologically fixed for all time. There is no carrying forward of apples, since they will rot.

In any period, there are only two agents alive. Each agent lives for two periods. This is an overlapping generations (OLG) model, such that in each period, one agent is Old and the other is Young. The colors are chosen to make it easy for you to see each person’s two-period lifespan.

Preferences are described by the utility function U=sqrt(A1)+sqrt(A2), meaning we take the square root of apples consumed as a young person and add it to the square root of the apples consumed as an old person. So there is no altruism or envy, and there’s no time preference per se (just to keep the math easier). However, there is a desire for consumption smoothing, because of diminishing marginal utility within each period.

In the top half of the chart, we see the laissez-faire outcome. Each person owns half of the apples trees, and ends up consuming (of course) 100 apples each period. There are no loans made in terms of apples, because there would be no point to them: everybody maximizes utility by consuming his personal endowment each period.

In the bottom half of the chart, the government interferes with the laissez-faire outcome. The government runs a “primary deficit” of 3 apples in the first period, in order to make a gift of 3 apples to Old Al. Then it just keeps borrowing more and more in order to roll over the debt (at 100% interest) until period 6, when it (for the first time) imposes taxes to start paying down the debt. The debt is finally extinguished in period 9.

By comparing their lifetime stream of consumption in the top half with the bottom half, we can see who gains and loses from this whole operation. Specifically, the first five generations (Al, Bob, Christy, Dave, and Eddy) benefit, while the last five generations (Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John) all lose. I have chosen blue colors to denote winners, and red colors to denote losers.

Here are some additional points about this example, to drive home why Dean Baker and Paul Krugman’s commentary has been so misleading–and why they still didn’t “get it” even as late as Friday October 12, in the quotes I provided at the beginning of this post:

==> There is no crowding out of private investment in this example. Real GDP is fixed at 200 apples per period.

==> This isn’t an issue of intra-time-period redistribution. The first five generations all benefit, the last five generations all lose. If this example doesn’t depict “the present voters using deficit finance to benefit at the expense of unborn future generations,” what would?

==> There are no foreign owners of government bonds. Each period, the government debt is “owed to ourselves.” But look at poor Frank in period 6. He is being taxed 86 apples and is then handed 96 apples by the government. The way Baker and Krugman have been guiding their readers through this, they would describe this by saying, “In period 6, that lucky ducky Frank actually gains 10 apples on net from the government’s operation, since he inherited all the bonds from people holding them in period 5.” Yet this is completely misleading. Frank is getting screwed more than any other person in the history of this economy.

Final point: It seems that by the next day, Saturday October 13, Dean Baker was finally starting to understand the gap in his arguments. But instead he played it off like this was some little technical quibble. If he had any honor, he would have said, “Holy cow! I have been writing complete nonsense on this matter for at least 11 months! Sorry everyone!” Yet, that’s not exactly how he phrased it…

Recent Comments