Harold Hotelling and Steve Landsburg vs Bob Murphy and George W. Bush

It doesn’t look good for me, does it? But give me a chance:

During his commentary on the first presidential debate, Steve Landsburg wrote:

6) Romney says “all of the increase in energy has been on private land, not govt land”. Very ignorant. If there were more drilling on govt land, there’d be less on private land (assuming there’s any truth at all to Hotelling style models and how can there not be?)

In case you want context for Romney’s claim, check out this IER blog post.

In the comments I said to Steve:

Steve, what’s your problem on #6? You don’t think it’s relevant that Obama is taking credit for a rise in domestic oil production, that occurred precisely on those areas where he doesn’t control? (I’m assuming Romney’s basic stat was right.)

Did Romney say, “Now if you had allowed for more drilling on federal land, Mr. President, then in the new general equilibrium, production on private land would have followed the same path”? Maybe he thinks that, but he didn’t say it, and total output would certainly be higher (and spot price of crude would currently be lower) if Obama gave green light to unrestricted drilling on federal land. So why was Romney’s response so ignorant?

Then Steve answered me in the comments by writing:

I don’t get [your claim about oil prices, Bob]. Oil is an exhaustible resource. Allowing drilling on federal land does not change the supply of oil and it does not change the demand for oil, so how can it change the price of oil?

Or to put this another way: Hotelling tells us that in the absence of supply and/or demand shocks, the price of oil has to rise at the rate of interest. The rate of interest is what it is, and doesn’t change just because part of the oil supply moves from below-ground to above-ground. So the path of oil prices is determined independent of whether you allow drilling on federal lands.

(The only exception would be if the President is capable of instituting a *permanent* ban on drilling, effectively taking the oil under that land out of the oil supply. But surely nobody believes that the current President can set drilling policy for 30 years in the future.)

Steve is referring to Harold Hotelling’s classic 1931 article on the economics of exhaustible resources (The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 39, pp. 137-175). With your permission, I will quote from my EconLib article on oil prices to understand Hotelling’s framework:

Assume that every last drop of oil in the world is conveniently located at the surface of the earth, dispersed among thousands of small pools, each of which is owned by a different individual. Each of these owners—who controls a tiny fraction of the world’s total stockpile of oil—knows exactly how big his own pool is, and the pools of oil owned by his competitors. Further suppose that it costs each owner virtually nothing to extract a barrel of oil and sell it on the market. Assume also that the cost of storing the oil is zero, and further that each owner can predict with perfect foresight the demand for oil at every date into the future. There is no doubt that the known oil in the various pools is the only oil that will ever be available. Finally, suppose that each owner is also quite confident that there will always be people wishing to buy some barrels of oil, for virtually any price, into the foreseeable future. Under these very unrealistic yet convenient assumptions, what can we say about the price of oil?

Harold Hotelling provided the elegant answer back in 1931. On the margin, an owner of the oil must be indifferent between selling an extra barrel of oil today—and earning the spot price—versus holding it off the market and selling it in the future. Since we have assumed away storage and extraction costs, and any risk that the quantity demanded of oil will drop to zero if the price rises too far, we can conclude that the spot price of oil (the spot price is the current price at any given time) must rise over time with the interest rate. For example, if a barrel of oil sells today for $100, and the interest rate is 5%, the spot price of oil in twelve months’ time must be $105 in order to make it worthwhile for the owner to keep some oil off of the market today and carry it forward to next year. The idea is that the amount he earns by having the oil sit in the ground must equal the amount he would earn in interest on a portfolio of bonds.

…

Of course, Hotelling’s Rule doesn’t tell us what the actual spot price is at any time; it merely tells us how quickly it must rise. To come up with the specific numbers, we would need to know the demand for oil over time. In a general equilibrium, the spot price would rise with the interest rate (Hotelling’s Rule) and consumers of oil would purchase their optimal number of barrels per day (depending on the price at the time), such that the total consumption into the future would just equal the original size of the pool.

I know there were some scoffers in the comments–both at Steve’s blog and here at Free Advice–who thought Steve was nuts for not seeing how a federal quasi-ban on oil development in certain areas is a leftward shift of the supply curve. But let’s be fair to Steve: What I think he’s arguing is that Obama can only postpone the development of oil in ANWR, offshore, etc. So in the new equilibrium, oil producers in Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Canada, and even in the US on private or state-controlled lands will just ramp up their production rate accordingly. Rather than oil flowing evenly from ANWR, Venezuela, and Canada in 2012 and also in 2042, instead we draw more quickly from Venezuela and Canada and not at all from ANWR in 2012, and then we draw less from Venezuela and Canada but more from ANWR in 2042. (That is an awful sentence but if you read it twice you will get what I’m saying.)

Needless to say, I think Steve is wrong on this. Let me give some quick reasons:

First, I defy Steve to dot the i’s and cross the t’s on the framework at which he is hinting in his remarks. He’s perfectly right, Obama can’t tie policymakers’ hands for the next 30 years. So let’s set up a general equilibrium model in which there is a fixed pool of oil (much much larger than the current “known reserves” value because oil companies only go out and look for more known reserves when it is profitable to do so) as well as a known demand schedule for oil, and where the spot price is set in a Hotelling framework.

However, let’s make a few tweaks for the sake of realism. Assume there is a random variable to determine whether ANWR and other federal lands are off- or on-limits for development in the ensuing decade. Furthermore, assume that the (known) planetary demand curve for oil starts shifting left in the year 2150, because other technologies have more than offset the growth in population and per capita energy consumption. By 2200 the global demand for oil is zero.

I think if you put in reasonable assumptions about the lag between getting the green-light and then the actual pumping of oil from ANWR etc., and further you make reasonable assumptions about the maximum rate of extraction (or if you want to get fancier, you have a rising marginal cost of extraction based on the extraction rate per well), then you would find in the general equilibrium, spot oil prices would fall (meaning current global oil extraction would increase) whenever the random variable had a “green light” realization. This would be true immediately, even during the start-up lag, because the other producers would forecast lower (future) spot prices and would ramp up their current production rates accordingly to maximize the present-discounted value of their operation in light of the new information.

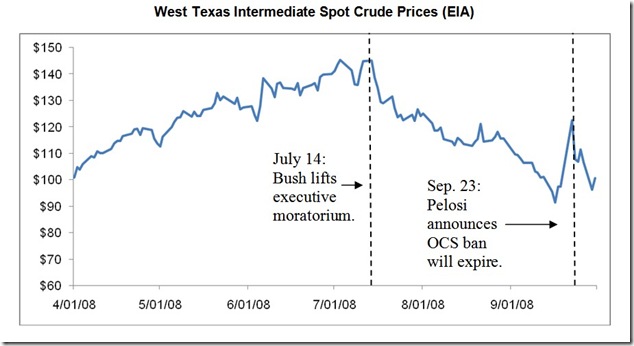

Second, in addition to the above Ivory Tower deep thoughts, we have this chart showing what happened to near-term oil futures prices when President George W. Bush in July 2008 removed just the Executive Branch moratorium on offshore drilling (which by itself had zero marginal effect) and then the Pelosi Congress allowed the Congressional moratorium on drilling in the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) to expire a few months later:

(This article gives the full context for the above chart.) As the chart above suggests, we economists need to start out with the Efficient Markets Hypothesis and Hotelling’s Rule on our blackboards, but I think we also need to realize that the real world apparently doesn’t work that way. So our job is to figure out exactly what is wrong with those elegant, baseline constructions, since the average Joe will say something like, “Well people aren’t rational.” I agree that that’s not a satisfactory refutation of the EMH, but something is sure screwy with it–or at least, with the conclusions that prominent economists draw from it.

Finally, a question for Steve: Suppose that the US government dropped a nuclear bomb on Iran, and that all politicians from both parties said they would continue this policy for years to come. If I understand your position, you would say that this could raise world oil prices temporarily, but only until (say) other, existing well operators could expand output? So maybe by 2016 you think that world oil prices would be back to what they otherwise would have been, even if–in 2016–the US is still periodically nuking the Middle East, and at that time there is no likely presidential candidate who pledges to stop?

Hmm I wrote “near-term futures price” but the chart itself (which I created in 2008) says “Spot Prices,” so maybe they are spot. Sometimes the data I get relies on one-month-ahead futures contracts.

Landsburg wrote:

I don’t get [your claim about oil prices, Bob]. Oil is an exhaustible resource. Allowing drilling on federal land does not change the supply of oil and it does not change the demand for oil, so how can it change the price of oil?

I think Landsburg’s confusion originates here. It is his understanding of the meaning of “supply.”

In economics, supply is not the physical totality of a resource that scientists estimate to exist. The supply of hydrogen atoms is not every single hydrogen atom in the Earth estimated by geologists. The supply of hydrogen is the totality of hydrogen atoms that owners of hydrogen atoms are able and willing to sell.

The same principle applies to oil. The supply of oil is not the totality of oil that physically exists in the Earth as estimated by geologists. The supply of oil is the totality of oil that owners of oil are able and willing to sell.

The price of oil is a function of this understanding of supply. Prices relate to goods, and goods relate to economized resources, not resources that are found to exist via observation.

Therefore, if the state allowed oil companies to drill for oil on federal lands, then the supply of oil would actually increase. With an increased supply, and assuming unchanged nominal demand, the price of oil will fall.

Murphy’s intuition is right.

The supply of hydrogen is the totality of hydrogen atoms that owners of hydrogen atoms are able and willing to sell.

Well, even more precisely, it's

In any case, Landsburg's remark is so ridiculous that you can show him wrong with even weaker assumptions than the ones you gave: say, that some oil sources might be held off the market forever, and the market prices in an estimate about how much of the global reserves this will remain true. Then, obviously, changing (sustainably) their uncertainty more towards "oh, that won't be permanently locked" means a permanent decrease in the price of oil relative to the alternative.

I think you accidentally a few words.

An example some could learn from MF!

Now now, no need to go from one extreme to the other.

There is a happy Ken B medium where not enough has been said to make it clear, and too much has been said to make it non-tedious.

Only one word. Just some nasty garden path sentences, I’m afraid.

“Thou shalt commit adultery”

“Coase’s Theorem justifies why thou shalt pay extortionists.”

“The supply of oil is the totality of oil that owners of oil are able and willing to sell.”

Right, and Murphy is saying that he thinks Landsburg is claiming that the totality of oil that owners of oil are able and willing to sell is unchanged regardless of whether or not at this time it is legal or illegal to drill on federal lands. Instead the only thing that will change is how much oil comes from where.

To be clear, I disagree with the claim that the supply of oil remains unchanged regardless of the legality of drilling on federal lands. However, Landsburg’s mistake is not in his definition of supply, but rather in the assumptions that make up his framework (as Murphy pointed out).

Right, and Murphy is saying that he thinks Landsburg is claiming that the totality of oil that owners of oil are able and willing to sell is unchanged regardless of whether or not at this time it is legal or illegal to drill on federal lands. Instead the only thing that will change is how much oil comes from where.

Right, that’s my point. To Landsburg, the oil supply remains constant because he views supply in terms of the physical totality of oil in the Earth, rather than oil economized by man and brought to market.

To be clear, I disagree with the claim that the supply of oil remains unchanged regardless of the legality of drilling on federal lands. However, Landsburg’s mistake is not in his definition of supply, but rather in the assumptions that make up his framework (as Murphy pointed out).

Which assumptions? The one above? That relates to what I argue is a misunderstanding of supply. If not supply, then what?

MF, to an economist, supply is not a quantity at all. It is a schedule. While you are accusing a noted economist of having a bad definition of supply, you have made a freshman error in your definition.

1. I didn’t supply is a quantity. I said supply is the quantity that sellers are able and willing to sell.

2. You are not talking about “to an economist”, you are talking about “to neoclassical economist”. Yes, to neoclassicals, supply is a hypothetical schedule, but that doesn’t contradict my statement that supply is the quantity that sellers are able and willing to sell. All you have to do to translate it into neoclassical parlance is to add “at a given price.”. Then you can construct the hypothetical supply “schedule”, which is…yup, a schedule of quantity of goods sellers are able and willing to sell.

3. You completely missed the main point I was making, which is that supply is not every good that physically exists. The goods have to be economized first before they can be considered a part of supply. Whether or not you want to interpret this via classical, neoclassical, Austrian, or my own interpretation that is a combination of classical and Austrian definitions, is subsidiary.

4. In your rush to do what you always do, which is try to knock down a few notches the person who constantly points out your errors, you have failed to see that the “noted economist’s” definition of supply was, as stated, in need of criticism.

In my line of work (engineering) when a belief relies on a list of patently absurd assumptions, you reject the belief. Not in economics it would seem. If a resource becomes more abundant over time (because reserves are discovered faster than consumed), would we really expect pricing to act like a capital good (future value of the total built in accounting for interest) and not more like a standard good that is being produced for consumption, where supply is the result of price and not the other way around?

More importantly, is “very ignorant” a good description of a presidential candidate failing to channel an obscure and rightfully controversial economic principle? Of the 538 people who make up the elected federal government (plus Romney), how many of them have even heard of Hotelling, much less understand it, much less believe it is true, much less would pull it out of their brains in a debate? This is Krugman level self-importance.

Ha! When I saw that title on my feed my first thought was “uh oh – that doesn’t look good for Bob”

Hi,

At the risk of showing my complete ignorance on this…How much does the value of the dollar play into the price of crude? I believe that oil is priced in dollars and I would assume that a devaluation of the dollar would cause crude prices to rise independent of supply/demand. I think that, ceteris paribus (one of the few economic terms I know – and I’m probably using it incorrectly :-): If the dollar lost 10% of it’s value there would need to be a corresponding 10% rise in the price of crude. Ben Swann (WXIX – Reality Check) did a piece a while back in which he mentioned that the price for a barrel of crude was tied to a certain amount of gold. So if gold prices go up, due to a falling dollar, crude will also go up.

And on the supply side of things…I’ve always assumed, and perhaps I’m way off base here, that: Because oil is a global market, the supply is measured in barrels world-wide. So if the bans were all lifted and oil was drilled in ANWR and other places in the U.S., how much additional supply, on a world-wide basis, would that actually mean? I know that it would shift the supply curve somewhat, but I’m wondering about the size of the relative shift.

And I think that the chart above shows the speculative nature of futures markets. Simply removing bans, or imposing them, doesn’t actually change the supply. All it does is change the perception of supply. A perceived increase, or decrease, in the demand should have a similar effect. So the fact that higher prices will mean less demand should also effect the perceived supply (unless a corresponding perception of shortage arises) driving prices down…right? So if I decided to live in a fantasy world, I could say that rising prices means lower demand forcing prices to stay, relatively, level…I know, it’s a fantasy 🙂

Sorry, I’m not an economist so I could be completely off on all of my assumptions. But I still wonder if it’s possible to look at crude prices from a purely supply/demand perspective. I think this is one situation where perception is more important than reality.

And just to clarify: I think I understand that the price of a good, the value of which is not tied to some other commodity, should fall/rise based on supply/demand of that good (I’ll ignore currency devaluation for now). I’m just not sure that applies to oil.

Dean T. Sandin has made a strong point. We don’t know how much oil there is. There is a lot of federal land and a decent chance of a big find there. Like the North Sea oli for the UK decades ago.

There is also the matter of extraction costs. These are high for places like Alberta’s oil sands, but once you reach the threshold price there is a LOT of oil to be extracted there. A find like the oil sands matters.

We are both pointing out that the small puddles of oil assumptions in Bob’s explanation is another wildly wrong assumption. Sometimes you find a huge reservoir, even on federal land.

Quick responses:

==> I agree with Dean and Ken B. that the Hotelling model is wrong. (That’s why I said in the post that I thought it was wrong.) Yes, one of the big problems (which I didn’t spell out) is that the “known supply of oil” typically increases over time, even adjusting for the increased rate of consumption. E.g. the “# of years of oil left” was something like 23 in the year 1980, but now is higher, even though more than 23 years have passed.

==> Having said all that, I’m not sure Ken B. that your latest formulation really hits the nail on the head. Yes, they might have huge finds on federal lands. But presumably the speculators in the oil market are aware of this as much as you are, and some might be so bold as to say their guesses are better than yours. What if it goes the other way, and the amount available on federal land turns out to be less than what people currently estimate? Then opening up federal lands would lead to a rise in the price of oil, if we just focus on the uncertainty of supply part of things.

==> I think the single biggest problem with Landsburg’s analysis is that marginal costs of extraction rise with a given well, after a certain level of production. Silas and MF, think of it this way: If there were a constant MC of extraction regardless of rate, and if we didn’t build in an assumption that at some (finite) distance in the future, the world demand for oil would be zero, then Landsburg wins. No matter how low the probability that ANWR and OCS can be developed in a given year, if we have infinity to play with, then the probability that they will eventually be allowed is 1. Then, in that year, people could pump out every last barrel from them, and use that to satisfy global demand that year. (Depending on the numbers, maybe it would take more than a year, but you get the idea.) So from our current perspective, there would be no doubt that at some point, every drop of oil in ANWR and OCS would get burned. The flow of oil from other sources would just be timed accordingly to offset the flow in ANWR and OCS. It was to get around this result, that I built in a maximum extraction rate and assumed global demand stops in 2200.

A good point in arrow 2 Bob, but then the opening up would still be a good thing wouldn’t it? Better knowledge leading to more efficient pricing long term?

I think the single biggest problem with Landsburg’s analysis is that marginal costs of extraction rise with a given well, after a certain level of production.

True enough, but this law of diminishing returns assumes that technology and capital accumulation remain fixed. You have a fixed A, B, C, and you continue to add more and more D, and at some point, you can no longer profitably produce that which requires all 4. For example adding more and more labor to a fixed area of land with fixed technology and capital equipment, will eventually lead to zero marginal output.

I think that gets you only do far though, because in the long run, technology and capital accumulation can overcome the law of diminishing returns so that we never get to that situation where we have a given well of oil, a given state of technology and a given quantity and quality of capital equipment.

Maybe this is adding in more assumptions that complicate the issue you are talking about, which prevents it from being isolated. I just think that the Hotellian assumption of every last drop of oil that physically exists, being available for sale to the market, is contradicting the whole meaning of supply, such that Landsburg made this statement:

“Allowing drilling on federal land does not change the supply of oil and it does not change the demand for oil, so how can it change the price of oil?”

I think the claim “does not change the supply of oil” is wrong. Oil buyers and sellers don’t take into account all the oil that physically exists in the Earth when setting prices. They take into account only that portion of oil that is or is capable of being brought to market within a planned time horizon that is encompassed in individual planning.

Suppose that tomorrow researchers discovered that the center of the moon is pure solid diamond. This discovery would, in Landsburg’s world, add to the supply of diamonds. The price of diamonds would almost certainly collapse. But then, also in Landsburg’s world, once that diamond is mined, and brought to Earth, it shouldn’t affect the prices of diamonds, because at that point, the Landsburgian supply of diamonds has not increased.

Silas and MF, think of it this way: If there were a constant MC of extraction regardless of rate, and if we didn’t build in an assumption that at some (finite) distance in the future, the world demand for oil would be zero, then Landsburg wins. No matter how low the probability that ANWR and OCS can be developed in a given year, if we have infinity to play with, then the probability that they will eventually be allowed is 1. Then, in that year, people could pump out every last barrel from them, and use that to satisfy global demand that year. (Depending on the numbers, maybe it would take more than a year, but you get the idea.) So from our current perspective, there would be no doubt that at some point, every drop of oil in ANWR and OCS would get burned. The flow of oil from other sources would just be timed accordingly to offset the flow in ANWR and OCS. It was to get around this result, that I built in a maximum extraction rate and assumed global demand stops in 2200.

I don’t understand why there is the assumption that “oil from other sources would just be times accordingly to offset the flow in ANWR and OCS.” Are we assuming an oil cartel that purposefully withholds supply from the market so that the rate of use/consumption remains fixed? Why are we assuming a fixed rate of use/consumption? I think I am lost on that one…

Is it relevant that there is to some extent, now or in the future, an effective oil producers cartel?

Just a few things off the top of my head:

=> The Efficient Markets Hypothesis, like the ERE, requires perfect foreknowledge of future conditions. So it is obviously merely another part of that unattainable ideal that is so common among supporters of government with their Nirvana fallacy.

=> The Hotelling Rule also requires that the ERE or general equilibrium is reached, and the production and transportation of crude is costless (instead of, as in the real world, increasing in cost over time), among other unrealistic assumptions. So it too is bunk as a useful analysis of the *real* oil market. It seems to me rather a case of economists’ hubris in deciding how things “should” work, instead of how they actually do.

=> Supply of oil is not “total amount of oil in existence” or “total amount of known reserves”. It is the total amount of oil that producers are willing to produce at sell at a given price. That appears to be causing Landsburg some confusion.

Supply of oil is not “total amount of oil in existence” or “total amount of known reserves”. It is the total amount of oil that producers are willing to produce at sell at a given price. That appears to be causing Landsburg some confusion.

I agree. That was my main criticism too.

Maybe it is not as clear with oil, but when used in other contexts, this assumption is more clearly seen as wonky. Imagine we consider the determinants of the price of silicon, or aluminum. Apparently, the price of silicon is a function of all the silicon that exists in the Earth, rather than the silicon that is possessed by owners of silicon who can actually SELL it as their property. But of course that is wrong.

All of your nonsense actually SUPPORTS your opponents. You say that one person’s spending doesn’t equal another person’s income because if a guy goes out of business do to a lack of customers, their money goes elsewhere. Well, that actually supports the circular flow diagram.

Second, if the EMH and the ERE requires perfect foreknowledge, and it doesn’t exist, how is that an argument the government? That would actually be an argument against markets – that they don’t create these equilibrium conditions.

The circular flow of income doctrine fails to take into account the fact that time moves forward, and that choices are sequential, not contemporaneous. In order to produce a pencil, or anything else, sequential steps one at a time, one after another, have to take place. The last step cannot generate the first step. The first step has to be made without thenlast step being present. The circular flow of income doctrine makes pedestrian pundits like yourself believe silly notions such as consumption spending drives the economy forward.

” You say that one person’s spending doesn’t equal another person’s income because if a guy goes out of business do to a lack of customers, their money goes elsewhere. Well, that actually supports the circular flow diagram.”

Where did I say that? And even if I had, the circular flow diagram is nonsense. Money never “circulates”. It is owned by one person at a time, who can trade it to others. It no more circulates in some flow than lawnmowers or computers. When will we talk about the circular flow of microchips?

MF is correct. The temporal nature of human action is ignored in the circular flow doctrine, and most all else of mainstream economics.

“Second, if the EMH and the ERE requires perfect foreknowledge, and it doesn’t exist, how is that an argument the government? That would actually be an argument against markets – that they don’t create these equilibrium conditions.”

The EMH is impossible because of a lack of foreknowledge (and this will introduce errors that would prevent the ERE from being attained even if the valuations of consumers never changed). But government has no additional knowledge here. The only difference is that when government makes mistakes, it is even harder to change. If I, as an imperfect consumer, buy something that does not help me as I thought, I merely stop buying it. If, as an imperfect producer, I produce things that consumers do not want, I am quickly forced to stop through losses. The government can continue indefinitely in both situations.

“Just a few things off the top of my head.” Bob should use that line, to prove he has skin in the game.

Perhaps, but my purpose in using the phrase was to indicate that my objections were not all that difficult to come up with – reading Landburg’s statement was enough to cause me to think “he’s totally forgetting or ignoring these things”.

Whereas Murphy makes a living on coming up with objections to stuff like that. He has to go a bit deeper, if only to have stuff to do during the day.

No deep thinking necessary.

Ken B. said what he said because Bob is bald.

It’s one of his best features!

I (sarcastically) wonder if Landsburg thinks the current price of various metal ores on the market accounts for near Earth asteroid deposits.

You write:

If there were a constant MC of extraction regardless of rate, and if we didn’t build in an assumption that at some (finite) distance in the future, the world demand for oil would be zero, then Landsburg wins.

But (correct me if you think I’m wrong) the non-constant MC of extraction becomes relevant only if a ban on drilling in location A leads to enough extra drilling in location B to *significantly* raise the MC of extraction at B. And since the slack from the ban at A is taken up not just by extra drilling at B but by extra drilling at B, C, D, E, etc., this seems unlikely.

It’s true that with a rising MC of extraction, the price of oil grows at something other than the rate of interest, but I trust we can agree that the price is still set by supply and demand. Surely a drilling ban has no effect on demand, so it can affect price only by affecting supply. I’m unconvinced that your assumptions are enough to imply that supply is affected.

Is there some other commodity where we can see if Hotelling works? Does anyone know the history of the price of amber? Because that is likewise a fixed non-renewable resource. Because I gotta say (and I doubt these words have ever been written or even thought before) I think Bob Murphy has the facts on his side.

“the non-constant MC of extraction becomes relevant only if a ban on drilling in location A leads to enough extra drilling in location B to *significantly* raise the MC of extraction at B”

What is a “significant” change here? Because, by definition, the marginal cost of extracting the oil at B, C, D, E, etc. will rise if they are tapped at less optimal rates in an attempt to meet current demand, as A is verboten.

Steve I will try to reply to this–you are making a good case. But can you quickly answer my nuking-the-Middle-East question?

Bob: I’m not sure I completely understand the premise of your question —- does “nuking” stop the flow of oil temporarily but not permanently? If so, I’d expect a one-time nuke to have little effect on the price of oil. Likewise for a policy of nuking once every other year. Of course, a policy of nuking-so-often-they-can-never-extract-their-oil-ever will affect prices.

I wonder if Keynesian remedy for liquidity trap is going to cause runaway inflation. After all they try to make people to hold cash as little as possibe.

It’s really insightful. How to resolve the slumping economy is really a daunting task. The debate between two parts is intense. The price of oil grows with the rising MC of extraction.

Bob—This one is not for you (because I know you already understand this) but for some of your commenters.

Suppose it is discovered today that there is a vast cache of diamonds on the moon, and that these diamonds can be cost-effectively brought to earth not today, but at some future date.

What is the immediate effect on the price of diamonds? Answer: Existing sellers foresee a lower price in the future and therefore are more eager to rid themselves of stock today. This bids down the current price. The easiest way to summarize this situation is to say that the supply of diamonds has increased and therefore the price has fallen. Anything diamond that can reasonably be expected to enter the market at some future time is in that sense a part of the *current* supply, and economists routinely use the word “supply” so as to account for this.

And I should have added: When there are multiple suppliers of an exhaustible resource, and when one of those suppliers is temporarily banned from the marketplace, his stock continues to affect the price, because everyone knows that if he sells less today he’ll sell more tomorrow. The supply is thus unchanged and so is the price.

Bob’s point is that things are a little trickier with rising marginal costs of extraction at each site. But I am quite skeptical that this is significant, per my reply to him above.

Bob’s ‘expiry date’ seems relevant too.

Steve, in your example you assume that the large cache of diamonds “can be cost-effectively brought to earth” at some point in the future, so therefore those diamonds should be considered part of the current supply which will have an effect on the current price of diamonds.

The significant detail missing, I think, is why those diamonds cannot be cost-effectively brought to market right away. If it is because the technology does not currently exist that will allow inexpensive extraction of the diamonds, then perhaps it is only a matter of time before it does and retrieval is possible, and therefore it is reasonable to think those currently unreachable diamonds are counted as part of today’s supply.

If, on the other hand, the reason the diamonds cannot be retrieved right away is because the government has made it illegal to do so, then it is not inevitable that those diamonds will ever be retrieved (because government may never change its mind). The fact that it is not a forgone conclusion the diamonds will ever be retrieved means (I think) they should not be counted as part of the current supply and price should not be affected by their mere existence.

JSR08:

Agreed. My presumption has been that no current ban on extraction has any significant predictive value for the legality of future extraction, because no administration can constrain the policies of future administrations.

Ah, so if you make an unrealistic assumption that you don’t mention, you can get a surprising result, since readers were wisely not making the same assumption.

Classic Steven_E_Landsburg.

No Silas, a truly classic Steven E. Landsburg involves something that will offend 75% of female readers. I don’t think this counts, since they don’t like Romney anyway.

Steve, couldn’t that reasoning be applied to any “thing” that government currently controls or in some has leverage over? I mean, for example, I could base my financial future on the belief that a future administration will give me a million dollars to retire with because “no administration can constrain the policies of future administrations” and that future administration could decide to give me a million dollars, but I think we all agree that is not terribly smart.

So you are left not with a usable prediction on when that oil will be available, but instead regime uncertainty, which is just as likely to assume that the oil may never be available for use.

People like diamonds, but they never get desperate for them. However, if and when oil reserves get low enough (and people are thus hungry and cold) or if a war breaks out (and people are faced with the choice of winning or losing) then you can completely guarantee that all available oil will become fair game.

It’s kind of difficult to allow for all the possible effects of government intervention in a politically sensitive industry — confiscation, price fixing, nationalization, insisting that the oil goes to military uses, etc.

The supply of diamonds on the moon would only affect current diamond prices if your assumption that those diamonds will be brought to Earth within people’s praxeological time horizons is true. Those diamonds that are not in this category however, will not affect the current price of diamonds. (I think you are granting this point to JSR08 below, but I’m not sure).

Your hypothetical Hotelling scenario of oil implied that the entire Earth’s physical supply of oil is within every seller’s praxeological time horizon, such that the current price of oil is now permanently taking into account the entire physical quantity of oil in the Earth. I submit that this assumption is not realistic. I think some of the other commenters are also questioning that assumption.

Thus, to me, your comment:

“Oil is an exhaustible resource. Allowing drilling on federal land does not change the supply of oil and it does not change the demand for oil, so how can it change the price of oil?”

seemed unrealistic. For the oil in/on federal lands is not necessarily being considered as part of the economic supply of oil by sellers.

You mentioned below that “My presumption has been that no current ban on extraction has any significant predictive value for the legality of future extraction, because no administration can constrain the policies of future administrations” I think gets you only part of the way to making your other quote convincing. For what if current oil sellers have time horizons that don’t extend as far as when they expect federal lands to be opened up? Even if oil sellers know that current administrations cannot constrain future administrations, this point is not enough to make the claim that every seller is considering federal land oil as part of the economic supply of oil.

Plus there is the other issue of demand elasticity, in which case we cannot presume fixed nominal demand for oil and hence cannot assume unchanged prices of oil should federal lands be opened up.

I think you got into trouble in reference to Hotelling. If all you had said was

“It is plausible that the marginal cost of producing oil over the last four years without using federal lands was about the same as if those lands had been open, and therefore the amount produced and the price to the consumer weren’t really affected”

then people might still disagree, but the arguments would be different. I’m on board with the plausibility of what you seem to be saying (though I strongly suspect it is not actually true), but the Hotelling explanation is completely absurd to me.

“The easiest way to summarize this situation is to say that the supply of diamonds has increased and therefore the price has fallen.”

Or, rather, that speculation of future supply increases has reduced the current price to account for this. Your summary is prone to induce erroneous conclusions, and apparently has.

The problem then, in your argument, is that the time at which said entry into the market will occur is unknown beyond “a long time from now”. Thus, the price will not likely be affected much by this speculation at all, as it will be discounted very, very heavily by the speculators.

“as it will be discounted very, very heavily by the speculators.”

Due to both time preference rates and uncertainty premiums due to regime uncertainty.

I’m not sure if Steve is meaning to use the term oil “supply” as an economist’s definition of “supply”, or rather more in the sense of “oil reserves”. It seems he is using the terms interchangably, but these two terms mean very different things. In my opinion, that is why it seems he is winning every argument, since he is using a slight of hand trick in definitions, without explaining what he is doing.

To make matters more confusing, when it comes to oil reserves, there are various categories such as proven producing reserves, proven undeveloped reserves, proven not producing reserves, probable reserves, and possible reserves. In geologic assessment of hydrocarbon reserves, there is even another category called “technically recoverable oil”. I think this last term may be closer to how Steve is using the term “oil supply”, except when he needs to use the term supply as an economists, to fend off an attach from a different direction. .

But if we are talking about supply schedules, then in the strict economist’s definition, supply is simply the amount of oil producers are willing and *able* to sell at the current market price. This would seem to imply that the concept of a fixed world supply of oil is an illusion. As demand rises, oil supply also rises, but also proven reserves rise as the price goes up. This is because there happens to be enourmous “technically recoverable” amounts of oil on planet Earth which are >> greater than proven reserves, and also >> greater than the oil supply at any given point in time. Then there is the matter of substitution which we have not even touched upon.

In the oil supply argument, I side with Julian Simons. Everyone should read Simons, and disbuse themselves of their Malthusian view of the world.

Thinking about this a little more:

Why would the same arguments put forward in Hotelling’s model not also be true for natural gas? Natural gas should be an “exhaustable resource” just like crude oil according to the proposed definition.

Yet if we look at the empirical divergence between the long term coupling of natural gas and oil prices in N. America, one possible explanation for the relative drop in natural gas prices might be that the *supply* (in the economic sense of the word) of natural gas in N. America has indeed increased much faster than the supply of oil.

But how have natural gas prices dropped during the same decadal time period that crude oil prices have risen ? After all, the total amount of new natural gas reserves that we supposedly found during the last 15 years in N. America were already a fixed “supply” buried deep within the global subsurface, and in the same worldwide aggregate gas to oil ratio.

Under the Hotelling model as put forth by SL, whether or not the government would or would not have banned shale gas drilling in year 2000 should have been largely a mute point. The natural gas would have simply come from somewhere else, and the natural gas price trajectory, along with the natural gas to oil price ratio should have stayed essentially the same with or without shale gas drilling.

Would that be the implication, or have I missed something fundamental?

I think that in the gas industry there are still plenty of new discoveries happening. Shale is now more useful than it used to be, also fracking, etc.

Probably there is a fixed supply somewhere, but we don’t know much about where the limit might be.

Also, as far as I know there is no OPEC equivalent for gas producers (maybe there will be at some stage).

It is still abusurd for me to think that if the Arctic were opened up, and an additional 5 million barrels of oil per day were to be brought on line, that it would not drive down the trajectory of long-term oil prices much the same way which shale gas has driven down the trajectory of natural gas prices in the U.S. After all, the United States producers could have theoretically imported LNG into the US to give the same natural gas output (and were making plans to do so prior to the shale gas discoveries), but such a supply would have necessarily been from more expensive LNG imports shipped from production projects with lower rates of return.

I agree that production from 10 wells capable of making an aggregate of 1000 BOPD is likely to be cheaper oil than the the same 1000 BOPD, but coming from 100 wells making 10 BOPD. Even in the high cost Arctic, this is likely to be the case. The new cheaper supply of crude will displace the more expensive crude. As the newly discovered cheaper supplies deplete into the future (become more expensive), it is more likely that substitues will become available which will make the need to go back and try to re-start the old depleted wells (more expensive oil) less likely. This must have an effect on even the long-term trajectory of the oil price, but we must consider the counterfactual as a comparison to see the possible benefits. The proposed model assumes that since the oil is already in the earth, that any additional producton cannot change the supply of oil, so thus not the price. It is an absurd.

This type of argument is akin to the argument which holds that if citizen investors buy governenment bonds today, that it does not make future citizens of that country poorer (public debt held internally does not affect the long-term wealth trajectory of the country). The argument implicity assumes that only government bonds were available as an investment option, instead of a full menu of investment options, which in comparison to government bonds, might have yielded better returns than the paultry yields they actually recieved. So the failure to consider the alternative case seems to prove the case for those saying that internal debt issue cannot make future generations poorer. The oil argument seems to me to be of a similar type. There is falacy there which common sense almost instinctively rejects, but some economists tell us that the unwashed Joe Public is “incredibly ignorant”.

“or if you want to get fancier, you have a rising marginal cost of extraction based on the extraction rate per well”

Typically oil wells having the lowest marginal costs of production are the wells with the *highest* producing rates. The cheaper barrels come from the wells and the fields that produce the most oil. The marginal cost of producing a barrel from Ghwar is much lower than the marginal cost of producing a barrel from a waterflood in West Texas, despite the fact that Ghwar produces oil at a much higher rate.

High-rate oil production typically flows and does not the high lifting costs associated with lower producing rate wells, The energy stored within a new oil reservoir brings the oil to the surface naturally.

For any given new oilfield discovery, the marginal costs of extraction typically go up over the life of the field as production rate falls. In a big field under depletion, it is almost impossible to actually increase the production rate of the field. The new investment into these fields typically slow down or temporarily arrest the rate of decline. But when we do this, new reserves are “found”, and new supply comes on line, since the shape of the decline curve has changed. But these are typcially barrels with higher marginal costs.

I’ll need to think about how this factors into the larger discussion, but I think some people naturally assume that if we want to increase the rate of production from a well or field, we simply invest in bigger pumps, and pump more oil. It does not work this way in low rate producing in fields. In the very high rate producing fields, it is often true that if we want to produce more oil, we simply open the valve more.

“or if you want to get fancier, you have a rising marginal cost of extraction based on the extraction rate per well”

In the oil industry, the only way we can actually increase oil production is to invest in both stabilzing the decline of old oil fields, and also invest in the search for new ones. So the marginal costs of actually increasing oil production rates indeed go up.

However, on an individual well basis, the lowest marginal cost wells are those with the *highest* rates of production. The slow oil is the most expensive to find and produce.

I think the statement was meaning more like:

“If we increase the rate of extraction at wells already in production, this will increase their marginal cost relative to the level they are already producing at.”

Thus, they would have a rising marginal cost as you increase the extraction rate. Basically, as I understood it, this is just the law of returns at work.

“Thus, they would have a rising marginal cost as you increase the extraction rate”

For individual wells, it usually does not work this way. The highest rate producing wells usually have the lowest marginal production costs. It is counterintuive. But think about it this way. Which is the more expensive oil to produce? Field #1 yields 1000 barrels of oil per day produced from 10 wells (100 BOPD/well). Field #2 yields 1000 barrels of oil per day, but produced from 1000 wells (1 BOPD/well). In this way it is easy to see that individual wells and fields producing at lower rates have the higher marginal costs.

Now visualize a world where both of these fields are the only two which exists, but there are 10 undrilled prospects, each with a 20% chance that an oil accumulation will exist, and a 90% chance that if oil is found, the accumulation will be at least large enough to yield 1500 barrels per day per prospect assuming a 10 well development plan, and decline at 5% per year. The only problem is that all 10 prospects are underneath the king’s favorite bird sanctuary, and he will not allow any drilling. The king is old, and it has been rumoured that when he dies, he will make four or five of these prospects available for drilling. There are no guarantees though.

However, the demand for oil in the model world is currently 2,100 barrels of oil per day and growing @ 2% per year, while the production in our two oilfields is declining at 2% per year, and will continue to do so unless new drilling is done in the old fields.

In the field with 1000 wells, engineers estimate that if 1000 more wells were drilled, production could be increased by 200 barrells of oil per day, but the new production decline rate will change from 5% per year to 10% per year. In the field with 10 wells, 10 new wells can be drilled to increase the production 500 barrels per day, but the new production decline rate will be 15% per year. So in our world, engineers tell us we can drill 1010 wells, and can expect to increase production 700 barrels per day.

Now suppose the old king dies suddenly, and new king surprisingly grants full access to all the new prospects have access to the new wildcat prospects. In this case, we would intially drill 10 wells, and might reasonably expect to discover 2 new oilfields capable of producing over 1000 BOPD each. A total of 20 wells in the newly accessable areas is now able to yield 2000 BOPD.

So assuming that the price of oil is driven by supply and demand, and barring any access restriction, marginal costs will indeed determine where drilling occurs. Under these different scenarios, it is not hard to imagine that the price trajectory of oil will be considerably different under the different access scenarios. In the unlimited access story, the oil production rate is much higher despite much lower marginal finding costs. There are more proven reserves, and the price of oil goes much lower even though the demand for oil is likely to grow faster than the 2% per year estimate in scenario 1.

Such a simple model indeed suggests that access to low marginal cost reserves matter, and yes, it will matter to the longer-term trajectory of oil price when this access is granted.

Finally, I hate to bring out this quote on Bob Murphy’s blog, but paraphrasing some dead economist, it may not matter in the long run, but in the long run we are all dead.