Did Jesus Die for Everyone’s Sins?

This post is intended for genuine believers in Christ, or at least, those who are intimate with the Christian worldview. If you are the type of person who thinks it’s completely obvious that there’s no God, that the idea of sacrifice or vicarious atonement is repugnant, etc., there are plenty of Sundays when I’m happy to debate you–but I am aiming this particular post at fellow believers.

So here’s my question: If we’re saying that only the elect go to paradise, and are “saved” through their faith in Jesus (which itself is not because of their hard work), then what does it mean when we say to anyone who will listen, “Jesus died for our sins” ? Doesn’t it sound like you really should be saying, “Jesus died for my sins, and maybe He did for yours too… Let me ask you a few questions and see if I can give you an educated opinion.” ?

Another common Christian statement: Jesus conquered death. Well hang on a second: If a bunch of people are going to hell, and are dead because of their sin, it sounds like we’re using “conquered” in an odd way.

I have used this analogy before, but I’ll repeat it: Picture a parent who took her 3-year-old to the park. He’s having a great time. But it’s time to go, and the Mom says, “OK Jimmy we have to leave now.” But Jimmy will have none of it. He keeps going down the slide, chasing other toddlers around, etc.

So the Mom says, “All right Jimmy, you can stay here if you want. But I’m going home.” She packs up the sippy cup and snacks, and starts walking to the car. “Bye Jimmy, I’ll see you later. I hope you don’t get too cold when it’s nighttime.”

Now if someone who had absolutely no clue about what it’s like to be a parent saw that (typical) scene, he might be aghast. “What a horrible parent!! She’s either lying to her poor little kid and scaring him half to death, or she’s the most sadistic adult I’ve encountered in a month! That kid is going to have all kinds of abandonment and trust issues later on.”

So I’m wondering if this is how we will all realize typical atheist critiques of the God of the Bible will sound, when we are reunited with Him in heaven and can understand exactly why He did everything that He did. Maybe we will see that yes even Jesus used imagery of unquenchable fire, but that was to drive home the point that you really don’t want to choose hell. You want to choose to follow your parent. Yet at the same time, your loving parent really wasn’t going to let you “choose” something that catastrophic because you had no clue what you were doing.

Let me say one last time in closing: I understand full well that there are a lot of scriptural passages that contradict me here, but that’s why I bring up the analogy of the mom threatening to leave her kid at the park. That bluff only works if the kid believes it. And in that situation, we can understand that it’s not a case of “lying to manipulate your kid,” or at least, that you would have to be completely out-of-touch if that’s how you chose to describe the situation.

Final point: I am not saying that I understand the full situation. What I’m saying is, we necessarily are like the 3-year-old in the analogy. No matter what the Mom said to him, he wouldn’t possibly conceive of how bad it would be if she really took off and left him alone. So please don’t tell me, “Bob, if the situation is more nuanced like you’re claiming, then Jesus would have just told us that.” No, He used parables all the time, because He knew even His closest disciples couldn’t see things at His level. So He had to dumb it down for them, and in so doing, certain things were rendered imprecise. So the one thing of which I am confident is that when we finally understand God’s plan, we will really feel with utter certainty that it was just. Right now, I have to admit that the standard atheist critique–“Your God says, ‘You better love me or I burn you for eternity.'”–isn’t nonsense.

Potpourri

==> Redmond and I talk about all kinds of stuff for a good hour. This is actually “new” stuff if you are bored out of your mind at work and want to have this going in the background…

==> The Center for American Progress recycles my backside.

==> My brother sends this compilation of impressions. The guy’s got 3 or 4 really good ones, including a surprisingly good Owen Wilson, but–as my brother pointed out–way too much Gary Busey. (It’s actually fun to have this going in the background; you can really hear his good ones come through.)

==> Another installment in the Messengers for Liberty series.

==> Danny Sanchez is not a good American.

==> The skittish von Pepe sends this paper by Gerald O’Driscoll on central banking.

==> Lew Rockwell and Joe Salerno preach the truth about violence (near the end).

==> Gene Callahan sends me to a clinic. (We told them to bill our grandkids.)

==> Tom Woods is aghast at today’s “conservatives.”

==> Mario Rizzo administers extreme unction on the market monetarists.

==> Fascinating monetary analysis on the 1930s from JP Koning.

==> Did I never post this? Tom Woods and I went after low-hanging fruit at HuffPo on Fed “myths.”

==> Gene Epstein tries to find me a scapegoat.

If You Could Ask Krugman Anything…

UPDATE: Video below!

Kojo Prah writes me:

Bob, I’m a student at Texas Tech University and I recently found out Paul Krugman will be giving a speech about the economic crisis with a Q&A at the end tomorrow the 25th. So I was wondering what question you would, if you were here, ask him.

I told him to ask, “What would you need to see, to make you change your mind on the importance of government fiscal stimulus?”

However, upon further review I would change it to:

“What would you need to see, to make your change your mind on the importance of government and Fed countercyclical policies?”

The reason for the change is that on the first version, I think Krugman would swat it away with something like, “*sigh* As I’ve written many times, I’ve been totally consistent on this point throughout my career. You only need fiscal stimulus when you’re at the zero lower bound and the monetary authorities are either too ignorant or too politically impotent to use unconventional operations. So, once we emerge from the zero bound, I too will call for reining in deficits. But that’s not the urgent danger right now.”

And, the above answer is not at all what I’m looking for. I’m basically asking, what would make Krugman stop being a Keynesian.

Of course, Mr. Prah wondered if he should bring up the Krugman Debate challenge. Perhaps because I had recently viewed the obnoxious Trump video (which Bob Wenzel was the first to bring to my attention), I told him:

Eh, I dunno. I don’t want people to be obnoxious on my behalf. Ideally you could hold up a sign or something that Krugman would see, but wouldn’t distract from the presentation to everybody.

I think it’s a judgment call you have to make.

UPDATE: Here’s the video:

Money Is a Spontaneous Order Not a Social Contrivance

Everybody has been talking about this “is money a bubble?” controversy. (Nick Rowe, in addition to being awesome on OLG apple models, is also good at linking everybody in this debate.) I want to make two main points:

(1) This isn’t even about fiat money per se. Even if we’re talking about gold, once it becomes used as a medium of exchange, it achieves an exchange value higher than what it had in direct exchange, precisely because of its new role. In other words, the demand to hold gold goes up, once it acquires a monetary demand in addition to its industrial/consumption demand. So I would caution Austrians not to say something like, “Krugman you idiot! Fiat money is too a bubble because of its very nature it’s worth zero, and eventually that’s where it’s headed!” To be clear, these are all defensible and plausibly true claims, but my point is, the mere fact that fiat money currently has a positive market value, by itself doesn’t guarantee that it must eventually pop. If you think that, then you would have to tell Mises that when he says gold acquires a value because of its use as money, then eventually the gold bubble must pop and gold’s value returns to the floor determined by its industrial/consumption uses. I don’t think most Austrians believe that. If you want to thread the needle you can argue something like, “The ‘bubble’ equilibrium for gold is more stable than for fiat money, because people know gold has a positive backstop value, whereas Benjamins have nowhere to go but doooooown.” So I’m just saying, be careful when attacking Krugman on this, that you don’t throw out gold with the bathwater.

(2) I really really don’t like the Samuelson idea of calling money a “social contrivance.” Here’s Krugman’s take on this, which epitomizes what I dislike:

So what is fiat money? It is, as Paul Samuelson put it in his original overlapping-generations model (pdf), a “social contrivance”. It’s a convention, which works as long as the future is like the past. Obviously, such conventions can break down — but then so can things like property rights. In fact, you could argue that almost every asset in a modern economy owes its value to social convention; green pieces of paper could become worthless, but then so could any paper claim, which is, after all, worth something only because laws say it is — and laws can be repealed.

Here, Krugman is making it sound as if fiat money has its value via the same mechanism that we decide when to hold Election Day. Or, to be more accurate, Krugman is making it sound like fiat money has its value for the same reason that people generally hold doors for each other, or help each other to move.

But this really misses what’s special about money, and other spontaneous orders, that are the “result of human action but not of human design.” (Ironically, I would say property rights are also an example of institution that wasn’t consciously designed, but Krugman is thinking of legislated property rights in government courts.)

The worst offender in this category was an op ed columnist (can’t remember who) who once stated something like, “Fundamentally, money is just a social convention. I agree to give you my stuff in exchange for your intrinsically useless money, but only because you agree to do the reverse in the future.” And that is not at all the way you should be thinking about money.

The single most important work on monetary theory is Ludwig von Mises’ classic, The Theory of Money and Credit. When the Mises Institute commissioned me to write a study guide for it, I confess I was thinking it would be a real chore, because I remembered working my way through it as a kid (either in high school or maybe freshman year in college, can’t remember) and finding it really difficult. But this time through, it wasn’t hard at all. I kept waiting for it to get tough, and it never did. (I’m not just saying I “got it” because I had a PhD in economics. I’m saying even for the lay adult reader, it’s not that hard.) It’s not a Dan Brown novel, to be sure, but it is still good ol’ Mises. And with my trusty study guide beside you, what’s stopping you from absorbing a proper understanding of money?

Callahan’s Unsustainable Attacks on Nick Rowe

Gene has been annoying me in the debate on a topic that shall no longer be mentioned on this blog (for calendar 2012 at least), with post titles suggesting that Nick Rowe is unfamiliar with the history of economic thought. Then in this post Gene accused Rowe of “arrogantly insisting” on the importance of his counterexamples.

In this context, I found it ironic to see Gene write:

Now, the intuition that I think is driving the use of this model is “But look: If Young Bob didn’t think he could get his apples back plus more, the thing couldn’t get rolling. And he has to convince Christy of the same!” Well, of course Ponzi schemes are (by definition) unsustainable, and of course if this debt financing has been sold to citizens as a Ponzi scheme, there will be trouble down the road. (If the economy grows faster than the debt re-payments, per Samuelson, then the debt financing is not a Ponzi scheme at all, or, perhaps, per Rowe, is a “sustainable Ponzi scheme.”)

Gene might be interested to read the history of economic thought chapter on Paul Samuelson, who wrote:

The beauty of social insurance is that it is actuarially unsound. [italics in original] Everyone who reaches retirement age is given benefit privileges that far exceed anything he has paid in. And exceed his payments by more than ten times (or five times counting employer payments)!

How is it possible? It stems from the fact that the national product is growing at a compound interest rate and can be expected to do so for as far ahead as the eye cannot see. Always there are more youths than old folks in a growing population. More important, with real income going up at 3% per year, the taxable base on which benefits rest is always much greater than the taxes paid historically by the generation now retired…

Social Security is squarely based on what has been called the eight wonder of the world — compound interest. A growing nation is the greatest Ponzi game ever contrived. And that is a fact, not a paradox.

My Final Word (This Generation): The DEBT Really Is Fundamental

If you have begun skipping these, I ask you to read this final word from me. This is new stuff.–RPM

OK kids don’t worry, this is going to be out of my system now, unless Krugman or somebody puts up something new. But I really wanted to illustrate the epiphany I had last Friday, which caused my acid-trip post. Before that post, I had settled this for myself, by thinking that it wasn’t really the debt per se that burdened future generations, but instead was the taxes levied on them.

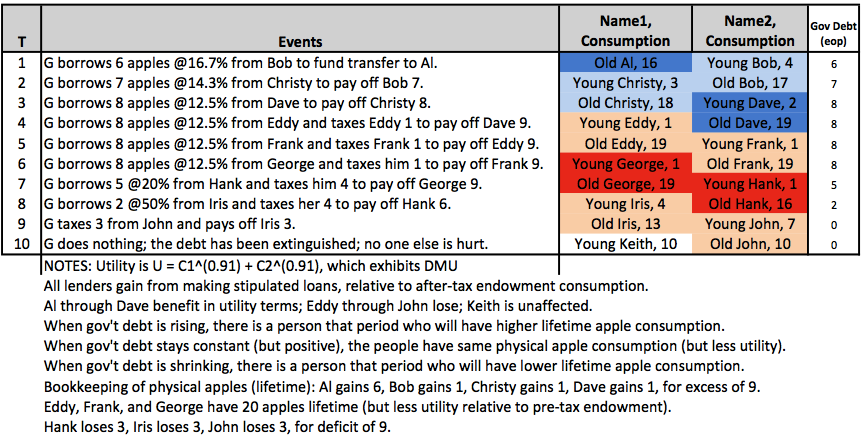

But now I disagree with that. Yes, the taxes on them are a burden, but if you want to avoid paying down the debt, then you are forced to pay higher interest on the debt. (In other words, if you are taxing future generations more than they are earning in interest on the debt they’re carrying, then you pay down the debt.) So the problem is, to make the lending to the government voluntary, you have to basically subsidize the lenders. Thus, if you are in a steady state where the level of the debt stays constant–where the government just keeps paying the interest each period–then the losses to people in the form of debt service payments are counterbalanced by the gains to the bondholders. (This is what made me think I was turning MMT.)

So now I’ve come full circle, and think it is more accurate to say that it is the debt per se that burdens future generations. In the act of running up a debt, the present generations gain not only in utility, but they physically consume more apples. And then, if descendants want to pay down the debt (not just roll it over), they not only lose in utility terms, but they literally put fewer physical apples in their bellies.

When I was puzzling over this outcome, something obvious occurred to me: What does it mean in financial, balance sheet terms to run up the government debt? I don’t even care what is done with the funds. Just focus on the act of the government printing up an IOU for, say, $10,000, and giving it to somebody who is alive today. What just happened, in financial accounting terms? Why, the recipient of that new bond gained an asset with a market value of $10,000. So somebody else must have lost. Who? The government, sure, but more strictly speaking it is the future taxpayers. The government, by running up a debt today, is effectively giving out claims on the income of future taxpayers. So I think that is fundamentally imposing a burden on them, just as surely as a family that goes out to dinner and puts it on the credit card, has surely benefited itself in the present by imposing a burden on itself in the future. Sure, when the bill comes due, the family can default, and at that moment transfer the burden to the credit card company. But nobody in real life would deny that at the moment of running up its credit card bill, the family has imposed a burden on its future self.

Without further ado, here’s an illustration of the above principles. I am pretty sure everything checks out internally. The only oddity is that the interest rate goes down with a higher volume of borrowing, but that’s just because I wanted an easy pattern in the debt movements and consumption patterns. Every lender gains from making the loans.

BTW, Nick Rowe is still my hero. I don’t think he ever had a misstep in this entire debate. Even on this issue of what happens if society just carries a positive government debt for a few generations, Nick instantly told me (paraphrasing), “They have the same lifetime consumption but their utility is lower. So they’re still hurt in the economically important sense.” But I needed to see it with my own eyes to “get” it…

Last thing: I’m not going to bother doing an illustration, but once you get the above, tweak the model so that some periods have really high apple crops, and other periods have awful harvests. So in principle apples from good years can be “moved” to apples in bad years. But there is a physical constraint on how much “time-shifting” can be done, because of the lack of a time machine. When you start thinking of it like this, the moralist’s worries about “not burdening the future with our debt” and the presumption in favor of “paying down debts in good years” is crystal clear. In contrast, if Krugman or Abba Lerner were advising the people in this world, during the good years they would tell them to not bother paying down the debt, since that couldn’t possibly help future generations on net.

Technical Bask: Easiest Way to Record an Audio Interview?

Hey kids, I am going to interview a Big Gun (not Rumseld, but someone you know) for an upcoming issue of the Lara-Murphy Report. The person is busy though, and wants to just do it over the phone (rather than typing in answers to a Word document I send, full of questions).

What is the easiest way for me to capture the audio on this (so I can transcribe it afterward)? For example, if we do a Skype call, can I record that?

Remember, I can’t even get the audio on my YouTube videos to work right (I think there was some background static on this latest one?), so treat me like I’m 5. Actually, treat me like I’m 75.

Recent Comments