More on Adapting to Climate Change

Blackadder was keeping me/us honest in the comments of my previous post on adapting to climate change. In particular, he thought I was being flippant in saying people could just move inward if sea levels started rising. It devolved (among him and other commenters) into an argument about the relatively pace of the increase, leading Blackadder to say:

Take a concrete example: New York City. If sea levels rise by several meters, then potentially much of it could end up under water. Granted, this would happen over the course of decades, but I’m not sure how that helps much. Saying “we’ll just wait for the individual buildings to wear out and then relocate them to Cleveland” is not a workable solution.

Fortunately, the “settled science”–as codified in the IPCC AR4–gives projections about sea level rises under various emissions scenarios, and they are nowhere close to what Blackadder mentioned above. Of course, Blackadder wasn’t saying he was accurately reproducing the best-guess estimates, but it is important I think for people to realize that what we are told is the “consensus” has this to say:

==> In the lowest emission scenario, sea levels in the decade 2090-2099 will be 18cm – 38cm higher than they were in the period 1980-99.

==> In the two middle emission scenarios, sea levels in 2090-99 will be anywhere from 20 – 48 cm higher.

==> In the highest emission scenario, sea level rises in 2090-99 will be anywhere from 26cm – 59cm.

Of course, it’s possible that sea levels will rise by several meters over the course of a few decades. But the latest IPCC report projects that in the middling emission scenario, over the next nine decades sea levels will rise about one-third of a meter.

Was Bernanke Able to Create More Money?

Since I usually agree with David R. Henderson, I like to highlight times when I think he is either wrong or (at least) paints a misleading picture for his readers. In this post David was reviewing Alan Blinder’s new book, and wrote (quoting himself from his WSJ review):

So once the financial crisis happened, what was to be done? Mr. Blinder devotes the bulk of his book to the immediate response to the crisis as well as to ways for avoiding a repeat. He praises the Troubled Asset Relief Program and points out that the net cost of TARP to taxpayers is not the $700 billion that was budgeted for but, rather, a much more modest $32 billion. But there was another way to go, the way Alan Greenspan handled the 1987 stock market crash, the Y2K episode in 1999 and 2000, and the post-9/11 economy. That way was to have the Fed purchase Treasury bills through open-market operations to make sure the economy had ample liquidity. In all three cases, it worked.

Many people think that that’s exactly what Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke did when the crisis hit, but he did not. Mr. Blinder, to his credit, recognizes this, pointing out that, although the Fed changed its composition of assets, it had little effect on the money supply. He makes this point briefly, but in a 2011 article San Jose State University economist Jeffrey R. Hummel provides chapter and verse, noting that Mr. Bernanke took on extensive discretionary power to favor some financial assets over others. As Mr. Hummel puts it, under Mr. Bernanke “central banking has become the new central planning.” Mr. Blinder seems to sense this but, unfortunately, does not pursue the point. [Bold added by RPM.]

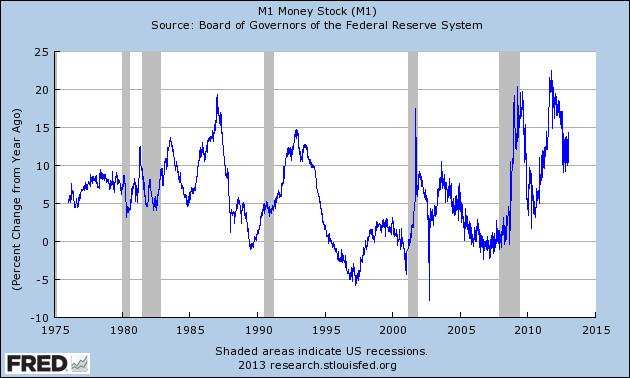

I explained in the comments that I couldn’t understand what David/Blinder meant by saying Bernanke’s policies had little effect on the money supply; whether we’re looking at the monetary base or M1, and whether we look at absolute or percentage increases, the spike during 2008-09 was bigger than in ’87, ’99, or ’01. Here is David’s response, but I don’t see how it helps. To say “it had little effect on the money supply” suggests to the average reader that the money supply didn’t increase as much under Bernanke as under Greenspan during the previous three crises, and that just isn’t true:

(Note that in my original comment at David’s post, I wasn’t sure about M1, but since then I checked the chart–shown above–and am now sure that not only the monetary base, but M1 also, rose more under Bernanke than it had ever done under Greenspan.)

If Blinder/David/Jeff Hummel/Scott Sumner want to argue that Bernanke’s actions haven’t done as much as the public probably thinks, I am open to hearing that. And it’s true that the financial pundits themselves can be misleading in the opposite direction–for example, the monetary base has been roughly flat since mid-2011, which is not what you might have thought if you read ZeroHedge every day.

All I’m saying is, I think we should be careful in how we describe monetary policy, especially since economists have such sharp disagreements about the proper role of monetary policy in a recession.

Adapting to Climate Change

David R. Henderson recently wondered what’s so special about current global temperatures, such that moderate warming will allegedly prove so damaging? After all, there have been larger swings in global temperatures in the past.

In the comments, the popular answer was that humans have adapted to the current climate. Thus, if the global average temperature that will in fact be achieved in the year 2100, had been the norm for thousands of years, then that would be one thing, but since people have settled in particular areas and adopted particular agricultural techniques etc., an increase to this (projected) temperature could be very harmful.

The major problem with this type of argument is that it ignores how much time people will have to adapt. I saw a funny stand-up bit where the comic said something like, “You know what the people on the coast should do when the sea level starts rising?” And then he took a big step backwards, on the stage.

Less flippantly, consider a new NBER paper that I discussed in this blog post. Here is the abstract of the paper:

Adaptation is the only strategy that is guaranteed to be part of the world’s climate strategy. Using the most comprehensive set of data files ever compiled on mortality and its determinants over the course of the 20th century, this paper makes two primary discoveries. First, we find that the mortality effect of an extremely hot day declined by about 80% between 1900-1959 and 1960-2004. As a consequence, days with temperatures exceeding 90°F were responsible for about 600 premature fatalities annually in the 1960-2004 period, compared to the approximately 3,600 premature fatalities that would have occurred if the temperature-mortality relationship from before 1960 still prevailed. Second, the adoption of residential air conditioning (AC) explains essentially the entire decline in the temperature-mortality relationship. In contrast, increased access to electricity and health care seem not to affect mortality on extremely hot days. Residential AC appears to be both the most promising technology to help poor countries mitigate the temperature related mortality impacts of climate change and, because fossil fuels are the least expensive source of energy, a technology whose proliferation will speed up the rate of climate change. [Bold added.]

Christianity Is Either Brilliant or Foolish

Sometimes I am astounded at how vehemently people argue when it comes to religion, but it actually does make sense. Take Christianity for example, which is usually the context for the arguments I see. If it were just a bunch of recommendations like “turn the other cheek” or “love your neighbor as yourself,” it wouldn’t be very controversial. But it also wouldn’t seem to be something of divine origin; you could imagine a clever person whipping up a list of such aphorisms.

Yet these aren’t the central tenets of Christianity. Here’s where we have to decide, is this brilliant or is it foolish? There’s no in between.

I remember when I was an atheist, thinking, “The problem with Christianity isn’t merely the implausibility of the gospel accounts. I can watch Star Wars and suspend disbelief about the Force, etc. No, the real problem with Christianity is that it makes no sense. God is mad at humanity because two people ate an apple, but then He forgives them when they murder His innocent Son. What the heck?!”

And yet, if you seriously entertain the notion that there is a God who loves us, and you can see with your own eyes what a bunch of scoundrels all humans are, then there is a certain beautiful logic to it, that it takes God to swoop in and save us from ourselves, through His own sacrifice. If you tried to build up a theology based on what makes sense in a secular context, it wouldn’t be divine. You would end up just making a Super President to lay on top of earthly rulers.

Bill Hicks (I think?) had a funny bit where he makes fun of Christians for adopting the cross as their symbol. He said something like, “That would be like fans of JFK wearing necklaces with little dangling sniper rifles.”

And yes, that’s funny because it’s true: From a human perspective, the Christian emphasis on the crucifixion is odd. Why call it “Good Friday” when–by our own beliefs–that is the day we humans mistakenly tortured and killed God’s Son.

Yet, if the context of the story is correct, then it makes sense. Isn’t a merciful, brilliant God just the sort of being who would devise a plan of cosmic justice, such that when Satan thought he had tricked humans into committing the ultimate sin, God transforms it into our ticket to paradise? It’s true, that’s never a myth I would have invented, because at first it sounds ridiculous.

But that’s the whole point of this blog post. If there really were a God of the kind described in the Bible, His plan would be like nothing you or I would invent.

Before I close, let me address one possible retort. I can imagine critics saying, “Well jeez, with that kind of argument, you can justify all kinds of nuttiness!”

But hold on a second. It is undeniable that there is something incredibly powerful and compelling about the gospel stories. They have inspired some of the greatest works of art, music, and literature known to man. Then, when you begin to study them with a rational approach, at first they seem to be absurd–but the more you study them, the more sense they make.

I submit that this is exactly what we would expect to observe, if the Bible were the inspired word of God.

Waldman Thinks Bernanke Will Go for (Flawed) Exit #1

Way back in March 2011, I had an article at Mises.org critiquing three “exit strategies” people had discussed for the Fed. The first was paying higher interest on excess reserves. Here was my analysis:

The option that Bernanke himself frequently mentions is the Fed’s ability to offer higher interest rates on excess reserves. Currently, if a commercial bank keeps its excess reserves parked at the Fed, the balance grows at an annual percentage rate (APR) of 0.25 percent, or what is called 25 “basis points.”

Now suppose (either because of rising price inflation or because of a healthy recovery) that the prime rate — what commercial banks charge their best clients — rises from its current level (3.25 percent) to, say, 10 percent. (This isn’t farfetched; the prime rate was higher than 10 percent in the late 1980s.)

Faced with earning a completely safe 0.25 percent by keeping their money parked at the Fed, versus earning a very (but not perfectly) safe 10 percent by lending to their most stable customers, many banks would begin drawing down their excess reserves, thus starting the inflationary spiral. To check this, the Fed could also bump up the yield it pays, to (say) 7.25 percent. By maintaining the spread between the two rates, the Fed could bribe the bankers to keep their money locked up at the Fed.

…

In any event, Bernanke’s favored “tool” of raising the interest rate on excess reserves is the epitome of kicking the can down the road. In the beginning, the higher payments would simply reduce the Fed’s net earnings, meaning that it would remit less money to the Treasury. Thus, the federal deficit would grow larger, meaning that taxpayers would ultimately be the ones paying bankers to not give them loans.But at some point, if the process continued, the Fed would have exhausted its income from other sources. For example, on a balance of $1.2 trillion, if the Fed had to pay 7.5 percent interest, that would translate into $90 billion in annual payments to the banks. (The Fed earned about $81 billion in net income in 2010, of which it remitted $78 billion to the Treasury.)

To be sure, nothing would stop Bernanke from making such payments. He isn’t constrained by income statements; Bernanke laughs at the shackles holding back lesser men. He could simply bump up the numbers in the Fed’s computers in order to reflect the growing reserves balances of the commercial banks if they kept their funds with the Fed.

But this would hardly “solve” the problem of excess reserves. Rather than facing a $1.2 trillion problem, the next year the Fed would face a $1.21 trillion problem, and so on. The excess reserves would grow exponentially.

In a running argument with Paul Krugman, Interfluidity’s Steve Waldman recently wrote:

Cash and (short-term) government debt will continue to be near-perfect substitutes because, I expect, the Fed will continue to pay interest on reserves very close to the Federal Funds rate…This represents a huge change from past practice — prior to 2008, the rate of interest paid on reserves was precisely zero, and the spread between the Federal Funds rate and zero was usually several hundred basis points. I believe that the Fed has moved permanently to a “floor” system…under which there will always be substantial excess reserves in the banking system, on which interest will always be paid (while the Federal Funds target rate is positive).

Ruh roh.

Friday Night Magnanimity

I just posted this comment over at The Money Illusion:

Scott, I don’t hope to convince you on this point, but for any innocent reader: I want to say for the record that Paul Krugman–my nemesis–has, since the late 1990s, consistently said that what Japan needs to do, to escape from the zero-bound liquidity trap, is to convince the public it will engage in future inflation.

Thus, I find it weird that when Japanese policymakers appear to be implementing Krugman’s solution, and it seems to be working just as he predicted, that Scott Sumner thinks this somehow embarrasses the Keynesians.

When Krugman is vanquished on the battlefield of ideas, I insist that it be a fair fight.

P.S. By “appears to be working” I just mean that the yen is falling, which is the evidence to which Scott points. I’m not saying the promise of more inflation by the BoJ is “working” the way Krugman/Sumner think, in terms of fixing the economy.

Potpourri

==> An interesting inventory at IER of “federal assets above and below ground.” I didn’t do this particular blog post, but I think it draws on some numbers I compiled in the past. This notion that if the feds don’t get to raise the debt ceiling, they have no choice but to cut PBS and Granny’s Social Security checks, is silly. (Not that I am in favor of PBS or Granny’s SS checks.)

==> If you think the trillion dollar coin idea is silly, you’ll like this cartoon (which the artist sent me today); otherwise, you will hate it.

==> An older post from Nick Rowe on “Dutch capital theory.” This guy is too clever by half.

==> Jeff Tucker’s tribute to Aaron Swartz.

==> JP Koning on the interaction of legal tender laws and purchasing power. I’ve often thought there was a gap in standard Austro-libertarian complaints about legal tender laws. The mere fact that Federal Reserve Notes are legal tender doesn’t pin down their purchasing power; merchants could say, “This item is either one ounce of gold, or 80 billion US dollars,” and debt contracts could have gold clauses in them. But on the other hand, there must be a reason they passed legal tender laws. I’m not saying JP has the full story, but he’s always interesting on this stuff.

==> Speaking of interesting! Next week–Monday through Wednesday–I’ll be giving a 3-part video series for the Laissez-Faire Club on Austrian business cycle theory. This is the most concise explanation I have given, so if you’ve never taken my more academic online classes because you’re too busy, this might be for you. Doug French explains it all here, in this pitch aimed at the investor/business owner demographic.

Daniel Kuehn, Like Krugman, Has Advice to Improve Jon Stewart’s Show

I know a lot of you ask, “Bob, why do you waste so much time on a Keynes-friendly grad student?” But it’s my blog. Go do something “important” on your blog, if you like.

Anyway, Daniel rushed to Krugman’s defense vis-a-vis Jon Stewart. The odd thing is, Daniel actually agrees with Stewart that the platinum coin idea is goofy and a distraction from the serious problems our noble leaders must face. So I was dumbfounded: Stewart was obviously funny, and he (according to Daniel) was correct in even his analysis of the platinum coin. So why isn’t this a clear-cut case of Krugman being toolish (not to be confused with foolish)?

It turns out that Daniel didn’t like the opening context Stewart gave to the original joke. OK, I challenged Daniel to say–in the same number of words, more or less–something that would have caused him to think the skit was hilarious, with no caveats. To refresh your memory, here’s what Stewart actually said, before going into his bit about, “Why don’t they just make it a quibbillion dollar coin?”

“Hey everybody you may be aware, America has a bit of a cashflow problem. With a $16 trillion debt, and the recent downgrade, it’s time to show the world we’re serious and restore the soundness of our currency.” [Not a literal transcript, but captures the gist, and might be missing a sentence.–RPM]

Here’s Daniel’s suggested replacement for the above:

“Hey everybody you may be aware, America has a bit of an unemployment problem. And even though nobody trusts Congress these days, people still consider the government such a safe bet they’re actually paying them to borrow money. But people from the right to the left still seem convinced its fiscal doomsday and insist that we don’t get paid to take other peoples’ money. So to get around Congress…”

Nope, sorry Daniel, if Stewart said your intro, and then went into his jokes about the platinum coin, it would have made absolutely no sense whatsoever. After further review, I still think Jon Stewart knows more about comedy than you or Paul Krugman.

But all is not lost. Daniel’s suggested intro would work, if, say, there were an economist who proposed paying one group of workers to dig ditches, and the other to fill them up, or who–oh I don’t know–proposed burying bottles of money in the trash heap, so that other workers would have to dig them up. Then Daniel’s intro would be a good setup, so we could all laugh at these idiotic proposals.

But for this idiotic proposal–to take a platinum coin and slap “ONE TRILLION DOLLARS” on it–nope, Stewart’s into works much better.

Recent Comments