Was Bernanke Able to Create More Money?

Since I usually agree with David R. Henderson, I like to highlight times when I think he is either wrong or (at least) paints a misleading picture for his readers. In this post David was reviewing Alan Blinder’s new book, and wrote (quoting himself from his WSJ review):

So once the financial crisis happened, what was to be done? Mr. Blinder devotes the bulk of his book to the immediate response to the crisis as well as to ways for avoiding a repeat. He praises the Troubled Asset Relief Program and points out that the net cost of TARP to taxpayers is not the $700 billion that was budgeted for but, rather, a much more modest $32 billion. But there was another way to go, the way Alan Greenspan handled the 1987 stock market crash, the Y2K episode in 1999 and 2000, and the post-9/11 economy. That way was to have the Fed purchase Treasury bills through open-market operations to make sure the economy had ample liquidity. In all three cases, it worked.

Many people think that that’s exactly what Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke did when the crisis hit, but he did not. Mr. Blinder, to his credit, recognizes this, pointing out that, although the Fed changed its composition of assets, it had little effect on the money supply. He makes this point briefly, but in a 2011 article San Jose State University economist Jeffrey R. Hummel provides chapter and verse, noting that Mr. Bernanke took on extensive discretionary power to favor some financial assets over others. As Mr. Hummel puts it, under Mr. Bernanke “central banking has become the new central planning.” Mr. Blinder seems to sense this but, unfortunately, does not pursue the point. [Bold added by RPM.]

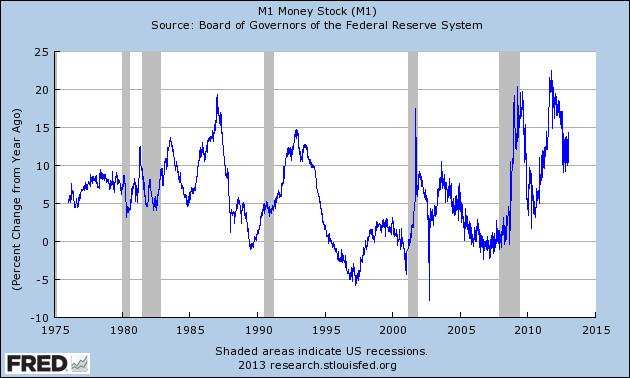

I explained in the comments that I couldn’t understand what David/Blinder meant by saying Bernanke’s policies had little effect on the money supply; whether we’re looking at the monetary base or M1, and whether we look at absolute or percentage increases, the spike during 2008-09 was bigger than in ’87, ’99, or ’01. Here is David’s response, but I don’t see how it helps. To say “it had little effect on the money supply” suggests to the average reader that the money supply didn’t increase as much under Bernanke as under Greenspan during the previous three crises, and that just isn’t true:

(Note that in my original comment at David’s post, I wasn’t sure about M1, but since then I checked the chart–shown above–and am now sure that not only the monetary base, but M1 also, rose more under Bernanke than it had ever done under Greenspan.)

If Blinder/David/Jeff Hummel/Scott Sumner want to argue that Bernanke’s actions haven’t done as much as the public probably thinks, I am open to hearing that. And it’s true that the financial pundits themselves can be misleading in the opposite direction–for example, the monetary base has been roughly flat since mid-2011, which is not what you might have thought if you read ZeroHedge every day.

All I’m saying is, I think we should be careful in how we describe monetary policy, especially since economists have such sharp disagreements about the proper role of monetary policy in a recession.

I don’t think its necessarily that the CB “haven’t done as much as the public probably thinks” so much as what they did in increasing reserves while paying IOR was never going to have the effect on nominal spending in the economy that those who saw a direct correlation between the monetary base and inflation assumed it would.

As Henderson says

“While reserves exploded, in a sense they were no longer reserves because the Fed began to pay interest on them, making them, in essence, loans from the banks to the Fed.”

I think the argument is that while the Fed has a lot of control over M1, it doesn’t have as much control over M3.

For the market monetarist crowd, NGDP is a function of the most widely aggregated money supply, M3.

http://i.imgur.com/wOrVDYl.gif

If we go by M3, Bernanke “failed” pretty badly post-2008, because the rate of M3 growth fell, and even went negative for a while until 2011.

It’s the massive credit deflation that often puts a monkey wrench in money discussions, because it can be subtracting huge quantities of money from the aggregate supply even while the Fed is massively expanding the M1 part of the money supply.

I think a stronger argument can be made by pointing out the simple truth that the central bank is not omnipotent. It requires positive choices of other people to spend more before NGDP or price inflation can go up the way the central bank wants. The market monetarist belief is that the Fed can make NGDP anything it wants by simply putting enough new dollars into other people’s hands that they cannot help but spend more. I think that argument is just a repetition of their belief in central bank omnipotence. It is based on a hope that people will spend the way you want them to spend provided they have enough additional dollars in their possession.

Well, when there is a widespread financial collapse, and those who the Fed primarily relies on to “spend” more are credit expansion lenders, then I don’t think that you can convince them to spend as easily as the omnipotence theory suggests.

Even if the Fed starts buying assets from every Tom, Dick and Harry in the country, it would still require the choices of others to spend more. Not only that, but this particular “solution” would defeat the purpose of central banking, and make inflation ineffectual at bringing about the kind of real side effects (employment, output, etc) that nominal targeting is supposedly capable of “stimulating.”

As long as the Fed depends primarily on money lenders to increase the money supply and NGDP, then M1 inflation is open to being overpowered by credit deflation in the market.

This is unrelated but might make Bob feel better about that $500 he lost to Henderson

http://www.news.com.au/business/economist-steve-keen-loses-housing-bet-against-rory-robertson/story-e6frfmbi-1225793985120

Just like we should separate theory from prediction in Austrian economics, I think the same thing should be done for all other schools too.

Of course, you probably won’t find Austrians engaging in the same type of haughty gloating and chest pumping that typically comes from many “you know who” non-Austrians when an Austrian makes a wrong prediction.

This is likely due to the fact that Austrians are the only economists who really understand why you can’t make scientific predictions of future learning and preferences using past data. They know there is no point to being obnoxious about other people’s wrong predictions.

“Was Bernanke Able to Create More Money?”

I think the answer will be highly dependent on what the definition of money is. It seems that Henderson doesn’t consider reserves to be very money-like since they paid interest. Thus he answers with a no.

MF points out that if our definition of money is M3, then Bernanke wasn’t able to create more money.

In any case, this is why I prefer words like moneyness and liquidity to money… perhaps it would be better to ask if Bernanke was able to create more liquidity, or something along those lines.

If you focus solely on the first part of 2008, the quantity of base money continued to increase pretty much like normal, but lending by the Fed increased very rapidly. The Fed sold off government bonds.

Starting in September of 2008, however, base money began to exand, though Fed lending expanded even more.

Interest on reserves was implemented in October at a relatively high rate of interest. By December, the interest rate on reserves (and the target for the Federal Funds rate) were dropped to near zero.

Since that time, lending by the Fed decreased while base money continued to increase–alot.

So, Henderson’s story is really relevant really up until the end of ,sometime in late 2008.

By the way, the Divisia measures of the quantity of money show a drop during this period that more or less tracks the drop in nominal GDP.

M1, of course, only measures reported checkable deposits and not the checkable deposits that are not reported because they are swept out before close of business. MZM covers many of the destinations of the swept funds, but not overnight repurchase agreements or overnight commercial paper. That stuff dropped tremendously. Other sorts of money market instruments, particularly T-bills became more “money like” according to the Divisia estimates, but the quantity of the private money market instruments dropped off so much that on the whole, the amount of money services dropped off more or less like spending on output. I don’t think Henderson is telling that story.

Has for M1, the total amount of funds that were really checkable probably fell off alot, but the amoun that the banks reported increased. The story with MZM is mixed, but it doesn’t include overnight repurchase agreements or overnight commercial paper. It does include all money market mutual fund shares, money market accounts, and checkable accouts. So, some desitinations of sweep accounts, but not all.

Again, M1 is completely corrupted by sweep accounts. It is worthless. I really think Divisia is the least bad approach to measuring the quantity of money. And it tracks nominal GDP pertty well. (I have “of course money demand can vary” priors and so find the close tracking of broad Divisia to nominal GDP very surprising.)

You’re using the term “money supply” to mean central bank printing specifically. Meanwhile, Henderson is actually alluding to the size of the credit market (whether he realizes it or not).

MF hit the nail on the head, a discussion about monetary expansion intended for the general public should never exclude analysis of the broader credit market which dwarfs the feds money-printing ability in comparison.

Mish is right about one thing, “the Austrians” (by which I think he means you and Peter Schiff) concentrate too much on $$ printing and too little on credit expansion.