Can Fiscal Austerity Work With Tight Money?

[Disclaimer: Bob Wenzel doesn’t like me using the term “fiscal austerity,” since he thinks the public associates it with jacking up taxes and cutting social programs in order to bail out bankers. He has a point, but it will just get too cumbersome in this post if I try to come up with some alternate term. So, when I speak approvingly of “fiscal austerity,” all I mean is the government cutting its spending in order to reduce deficits. Also, I would like to thank the supportive von Pepe for encouraging me to write up this post.]

In my latest EconLib article, I show that the peer-reviewed economic literature is far friendlier towards “expansionary austerity”–the idea that reining in budget deficits through spending cuts can actually boost economic growth, even in the short term–than prominent Keynesians would lead you to believe. (David R. Henderson thinks it’s “one of [my] most important” EconLib articles yet, and recent events have proven that David’s model of the world is spot-on.)

Lars Christensen at the Market Monetarist blog generally likes my article, except he thinks I am ignoring the crucial role that monetary policy plays in all of this:

The Danish and Irish cases are hence often highlighted when the case is made that fiscal policy can be tightened without leading to a recession. I fully share this view. However, where a lot of the literature on expansionary fiscal contractions – including Bob’s mini survey of the literature – fails is that the role of monetary policy is not discussed. In fact I would argue that Denmark was a case of an expansionary monetary contraction – a the introduction of new strict pegged exchange rate regime strongly reduced inflation expectations (I might return to that issue in a later post…).

In all the cases I know of where there has been expansionary fiscal contractions monetary policy has been kept accommodative in the [sense] that nominal GDP – which of course is determined by the central bank – is kept “on track”. This was also the case in the Danish and Irish cases where NGDP grew strong through the fiscal consolidation period.

My view is therefore that that fiscal austerity certainly will not have to lead to a recession IF monetary policy ensures a stable growth rate of nominal GDP. This in my view mean that we will have to be a lot more skeptical about austerity for example in Spain or Greece being successful….

All the cases of expansionary fiscal consolidations I have studied has been accompanied by a period of fairly high and stable NGDP growth and the unsuccessful periods have been accompanied by monetary contractions. My challenge to Bob would therefore be that he should find just one case of a expansionary fiscal contraction where NGDP growth was weak… [Bold added.]

Now right off the bat, look at how loaded the deck is, in favor of the market monetarists. Of course, if they’re right then it doesn’t matter that the deck is loaded; they should still win the argument. But if they’re wrong–which I think they are–it makes it hard for me to prove it.

THEORY

What do I mean? Well, suppose a new president (perhaps a fan of this blog) takes office in a small country and (a) cuts government spending by 30% in one year and income taxes by 15%, in absolute terms, and (b) abolishes the central bank and ties its currency to gold. A large budget deficit is transformed in one year into a modest surplus. Further suppose that my wacky Austrian views happen to be right–and Lars/Scott Sumner are utterly wrong. What happens?

Well, because I’m right (by stipulation), the real economy is just fine. There might be an initial period where the official unemployment rate in the country shoots through the roof, because workers have to move out of government (or government-subsidized) sectors, and into purely private sectors. But the big tax cuts and stability provided by the new gold standard, as well as the drop in government borrowing, lead to a fall in interest rates and a surge in private investment and job creation. Within 6 months, the unemployment rate is below the level at the start of the policy change. For the year, real GDP is up 8% when all is said and done, while consumer prices fall 2%.

Now I would look at this as a stunning refutation of Lars’ views, and a great counterexample. But he would look at the figures and say, “What do you mean Bob? Clearly maintaining aggregate expenditures was crucial for that giant reduction in government spending to work out. Nominal GDP rose 6% during the year, and interest rates fell. It was only the relatively loose monetary policy that offset the fiscal contraction.”

Does everybody see what I’m saying? Lars has defined “accommodative monetary policy” in such a way that I would have to find a government that simultaneously slashed spending while deliberately engineered massive price deflation. If the market monetarists are wrong, then it means a government could enact very tight restrictions on monetary inflation–perhaps going back on gold–and yet their own metric would classify that as “not tight” so long as the economy didn’t collapse. That is not a good way to think about these issues, especially since the very issue under dispute is whether the market monetarists are right.

Furthermore, it’s not even an absolute value of NGDP growth that’s at issue. If I understand Sumner’s worldview, the reason “NGDP matters” is that workers and firms sign contracts that have nominal values. So, suppose I find an example from 1880-82 where a European government slashes spending by 30%, and the economy doesn’t falter. Furthermore, NGDP is flat throughout the period. Did I just win? No, because Sumner can say, “Hang on, this country was on the gold standard. For the prior decade, prices had generally fallen about 2% per year, and real growth was 3% per year, so NGDP growth was only 1% per year. Thus, NGDP being flat from 1880-82 was only 1 point below trend per year. Compared to the fiat money era, flat NGDP would indeed be scandalous, but back then it wasn’t that far below the norm, and so people’s nominal debt burdens wouldn’t have been much harder to service.” (I’m making up the numbers for this hypothetical 1880-82 scenario, but I’m just showing how incredibly difficult it would be to actually find a counterexample to the Sumnerian explanations.)

Finally, as an Austrian economist who endorses Misesian business cycle theory, I admit upfront that it’s going to be hard to find a deliberately contractionary fiscal and monetary policy, leading to economic expansion even in the short term. That’s because I explain recessions as due to a switch from loose to tight money, where I define those terms differently from how a market monetarist would.

HISTORY

I’m not going to give a perfect counterexample–since, as I explained above, that would almost be impossible in principle, even if the market monetarists are totally wrong–but World War II offers something pretty close. Let’s work through two graphs and see why.

This first graph shows the level of NGDP, current government expenditures (note that this isn’t the same thing as “how much money did the government spend those years?” but it’s close enough), and the monetary base. Notice that I put the monetary base on the right axis, so you could see it better.

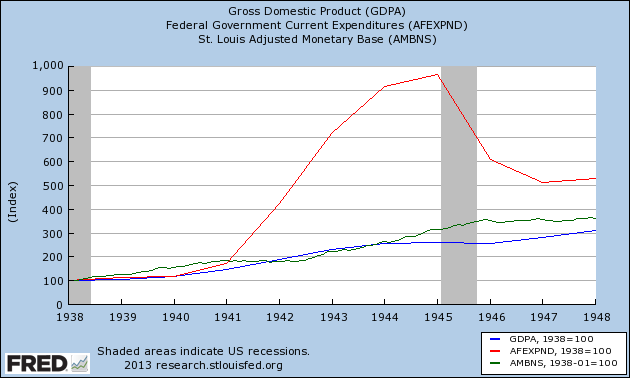

In the next graph, I’ll show the same three variables, but this time as an index=100 at 1938 (and now of course they’re all on the same axis):

Now this is really the killer chart. From 1945-46, clearly there was a more severe contraction in fiscal policy, than a corresponding looseness in monetary policy, if we are going to use those terms in a way that is useful in refereeing the claims of the market monetarists. Furthermore, coming off of five years of rapid NGDP growth, now it is flat.

Of course, the obvious MM response is to say, “Right! And notice there was a recession right then, just like we’d predict.”

But the free market camp can’t have it both ways. We’ve been congratulating ourselves for years now on how the Keynesians were wrong for predicting a postwar depression. (Look what our gloating did to poor Daniel Kuehn.)

Now if we move on to the next year, 1946-47, it’s very interesting. Just eyeballing the chart it looks like government current expenditures (again, this term doesn’t mean what you probably think–I ran into this issue on a major paper last year) fell about 15 percent, the monetary base was about flat, and yet nominal GDP growth was quite strong (in percentage terms). So I’m guessing Lars would say, “Right, accommodating monetary policy!” even though the monetary base growth came to a screeching halt after half a decade of rapid growth.

I don’t have good NGDP figures, but I imagine you would find the same pattern–perhaps even more so–if you looked at the end of World War I, where the Fed engaged in unprecedentedly tight monetary policy, and the government slashed spending tremendously. (I give the stats here.) Yes, there was a sharp depression, but it was soon over and paved the way for the Roaring Twenties.

CONCLUSION

I admit I have not found the smoking gun Lars wanted, but I hope I’ve shown why that is almost impossible, even in principle, given that I believe in Austrian business cycle theory. In any event, market monetarists shouldn’t ever roll their eyes at Keynesians who refuse to see the difficulties that particular historical eras provide for their theories. This is because from my perspective, both camps have a tough time explaining why the US bounced back so quickly after 1920-21 and 1945-46, if their explanation of 1929-1939 is correct.

Don’t Let Scott Sumner Write the History Books

Despite my title, this is actually a post about Brad DeLong, where I’ve noticed this trend the most. Now despite the recent unpleasantness, I’m not even criticizing DeLong in this post. I’m simply pointing out a rewriting of history that I am watching unfold before my very eyes, and I want to point this out to fellow econ bloggers.

Here’s how DeLong introduced a recent panel titled, “STIMULUS OR STYMIED?: THE MACROECONOMICS OF RECESSIONS”:

DELONG: Between 1985 and 2007–the period of the “Great Moderation”–the Federal Reserve and the rest of the U.S. government on the west edge and the central banks and institutions of the European Union on the east edge of the Atlantic Ocean provided a broadly stable macroeconomic environment within which private-sector businesses, workers and investors could make their economic plans. In the U.S., on an annual basis: the rate of nominal GDP growth dropped below 4% for only 3 of those years and rose above 7% for only 2 of those 22 years; the rate of consumer price inflation rose above 5% for only 3 and fell below 2% percent for only 2 of those 22 years; and the civilian adult employment-to-population ratio remained between 60% and 64% for that entire period. And Western Europe experienced a similar “Great Moderation” with low inflation, relatively smooth growth, and diminishing unemployment.

As Robert Lucas put it in those halcyon days: “the problem of depression prevention has been solved”.

Then in 2008-9 the rate of nominal GDP growth in the U.S. crashed to -3%–a major, major downward surprise to anybody expecting and relying on a continuation of “Great Moderation” rates of nominal spending growth–the rate of consumer price inflation on an annual basis bottomed out at -2%, and the employment-to-population ratio dropped from 63% to between 58% and 59%, since when it has flatlined. [Bold added.]

DeLong is making it sound as if economists thought about the Great Moderation, and our sudden departure from it in 2008, in terms of nominal GDP growth. No no no, they/we absolutely did not. Yes, Scott Sumner and his five heroes thought like that for decades, but that’s not how anybody else thought about it. During 2008 and early 2009, barely anybody besides Sumner was thinking, “Holy cow! How can Bernanke be allowing nominal GDP to fall so much?!” At the time I had to convince myself of what “NGDP” was. (And by the way, it’s not “total spending” and it’s not “total income.” Those are three different things, even though market monetarists use them interchangeably. But I digress.)

Just to see if maybe I was the one with my head in the sand all these years–maybe I was out sick all the days in my doctoral program from 1998-2003 when everybody talked our ears off about NGDP trend growth–I went to the Wikipedia article on “Great Moderation.” As expected, nothing in there about nominal GDP. Then I looked at the Stock and Watson paper. Nope, nothing in there; they talk about the declining volatility in real GDP. Then I checked Bernanke’s 2004 speech on the topic; nothing in there either about nominal GDP.

In conclusion, let me be clear about what I’m saying in this post: If Scott Sumner has convinced you that the reason for the Great Moderation, and for our current woes, is all about the NGDP growth, the whole NGDP growth, and nothing but the NGDP growth, that’s fine–maybe you’re right. And of course, economists who were in macro all understood what NGDP was, and may even have been remarkably close to some of Sumner’s views (Bernanke being an obvious example).

But what is demonstrably wrong is to discuss the history of economic thought as if this is the way most economists have always thought about macroeconomic fluctuations. DeLong’s narrative above strikes me as coming very dangerously close to doing that. It is simply not true that economists thought of the Great Moderation as being about stable growth of NGDP, and that the economics profession was stunned at the NGDP fall in 2008-09. No we weren’t. It took Scott Sumner years to get some economists to think that way, and there are many of us who still don’t.

Interest Does NOT Equal the Marginal Product of Capital, Even in Equilibrium

Oh man, here I’m trying to really be productive. I have even come up with strict limits on my Facebook time. And then Nick Rowe goes and starts posting on capital & interest theory!

Here’s the situation in a nutshell. In mainstream economics, it is commonplace for people to say that in a competitive equilibrium, the interest rate equals the “marginal product of capital.” This is considered to be analogous to the claim that in a competitive equilibrium, the wage rate equals the marginal product of labor. After all, the thinking goes, interest is the price (or opportunity cost) of using another unit of capital, and the marginal return to capital is diminishing, so firms use more and more capital until the point at which r*=MPK (in standard notation). Just like, firms keep hiring workers until w*=MPL.

The only problem with all of this, is that it’s totally wrong. Besides all of the critiques you might raise about formal modeling etc., there is a qualitative sense in which interest does not have anything to do with the “marginal product of capital,” in the way that we can plausibly say that wages are intimately related to the marginal product of labor.

Now the Austrian School has had a bee in its bonnet over this issue since at least Bohm-Bawerk, and his famous critique of “the naive productivity theory of interest.” (I give the details for a layperson here.)

And yet, if you go to the trouble of learning modern techniques for mathematical models of the economy, it seems that r=MPK just pops out of the model. There’s nothing wrong with the math. So what the heck is going on here? Was there a flaw in the Austrian verbal logic, that the precise mainstream guys blew up?

Nope, not at all. What’s happening is that the standard r=MPK result–where MPK is defined as the increment in physical output from an additional input of capital into the production function–crucially assumes that the capital and consumption good are the same physical things, or at least, that they are always physically convertible into each other in a constant ratio.

If you can read the notation, I think I showed very clearly in the Appendix of my dissertation. I had a model with a distinct capital and consumption good, and then derived the expression for the equilibrium interest rate. It wasn’t at all r=MPK, because you had to worry about the changing market value of the capital good vis-a-vis the consumption good. But, if you assumed that they always traded at par against each other (which would of course be true if they were the same thing, as one-good models assume), then my expression reduced to r=MPK.

Nick Rowe is groping towards the same type of result. (I’m not saying “groping” to be disparaging; he is admitting upfront that his modeling is a bit off.) Here are the crucial passages from his post:

Here is the simple aggregate technology macroeconomists often assume:

C + I = F(K,L) where I = dK/dt (I have ignored depreciation for simplicity).

Some economists object to the right hand side of that equation. They complain that it aggregates all labour into one type of labour L. And they complain that it aggregates all capital goods into one type of capital good K.

But I object more to the left hand side of that equation.

It aggregates newly-produced consumption goods C with newly-produced capital goods I. It assumes they are perfect substitutes in production. It assumes the Production Possibilities Frontier between C and I is a straight line with a slope of minus one. It assumes the opportunity cost of producing one more capital good is always and everywhere one less consumption good. It means that the price of the capital good will be always one consumption good. And that means that the (real) rate of interest will always equal the marginal product of capital.

We don’t assume a straight line PPF between two different consumption goods. Why should we assume a straight line PPF between consumption goods and capital goods?

…[This approach] also shows what’s wrong with “r = MPK”, in a simple model.

You could add in a second capital good if you like. Just add K2 to F( ), and I2 to H( ), then you get a second equation for Pk2, for R2, and for r as a function of Pk2 and R2. But I don’t think it makes as much difference. The problem is not aggregating capital goods. The problem is aggregating the capital good with the consumption good. [Bold added.]

When I’m not daydreaming about becoming today’s Bobby Darin, I imagine I have tenure down the hall from Nick. We go to lunch, and talk about overlapping generations and then robots that can build copies of themselves.

Thoughts on Glenn Beck

Well the big to-do in my Facebook circles is Glenn Beck’s announcement that he’s rebranding his “The Blaze” as a global libertarian network (HT2 DK).

Not sure if you guys remember, but years ago I had thought Glenn Greenwald was being too harsh on Beck. “Hey the guy is obviously putting on a show, but for a radio and TV personality the message is pretty good right?” No, Glenn Greenwald blew me up in the comments here, among other ways by linking to the below video. (See, I admit when I am wrong. Glenn Greenwald killed me in that particular argument.)

America’s Platinum Express

I have a question and a comment:

==> The “trillion dollar coin” thing is just because a billion is too little, and a quadrillion is too much, right? For example, there’s nothing to stop them from using this “option” but doing so by minting, say, 10 coins each with a face value of $100 billion?

==> Look at this comment from Krugman:

Don’t like the platinum coin option? Here’s a functionally equivalent alternative: have the Treasury sell pieces of paper labeled “moral obligation coupons”, which declare the intention of the government to redeem these coupons at face value in one year.

It should be clearly stated on the coupons that the government has no, repeat no, legal obligation to pay anything at all; you see, they’re not debt, and therefore don’t count against the debt limit. But that shouldn’t keep them from having substantial market value….

And maybe the coupons wouldn’t have to be sold on the open market; why not just have the Fed buy them? Bear in mind that the Fed doesn’t always buy safe assets; it’s buying a lot of mortgage-backed securities (from Fannie and Freddie; see above), and during the worst of the financial crisis it bought lots of commercial paper. So why not slightly speculative pieces of paper sold by the Treasury?

…

Update: If there is a legal problem even with selling these coupons, there are still alternatives, such as paying suppliers with these coupons and then having the Fed buy them. The mechanics really don’t matter; as long as we’re in a liquidity trap, printing money, printing conventional debt securities, or printing funny money with no legal standing that nonetheless lets the government pay its bills are all equivalent. [Bold added.]

Does everyone see how crucial it is for the Fed to have the power to buy any kind of asset it wants? This is exactly the sort of slippery slope some of us have been warning about.

Even if you are Scott Sumner himself, you should be very alarmed when you’ve now got arguably the most prominent economist on Earth arguing that the government should start paying its bills with coupons that are then monetized by the Fed. That is just the barest step removed from having the Fed literally create new money to cover the government’s spending.

Forget the macroeconomics for a second. Surely there is the faintest hint of Public Choice economics buried in the souls of the market monetarists. Can we all agree that Krugman’s flippant remarks above are downright alarming? It’s the economic equivalent of people casually talking about the president having the power to blow up American citizens on a secret kill list with his fleet of flying killer robots.

Two Visions

==> On the one hand, you can listen to Danny Glover and write-in Paul Krugman for Treasury Secretary.

==> On the other hand, you can sign up for Joe Salerno’s 6-week Mises Academy class on Austrian macroeconomics.

Potpourri

==> Jeffrey Karl made up this cartoon based on the numbers I calculated for the so-called fiscal cliff.

==> You can’t imagine how many people sent me this link about Krugman for Treasury Secretary.

==> Steve Landsburg disagrees with David R. Henderson’s (limited) defense of the recent budget deal.

Don’t Rush to Judgment

I can’t give any of the details, but there were several incidents this week in my personal life where a few different people, observing just snippets of my actions, might very understandably get upset with me. The thing was, in each of the cases, if the people could see the bigger context and why I did what I did, then they would either have been less upset, or in some cases not angry at all.

I’m sure that has happened to all of you reading this. When you’re a little kid, you imagine you can go through life without “getting in trouble” so long as you follow a simple set of rules. But as you get older, that gets harder to do. It’s not just that you are tempted to sell out for money or whatever, but even if you are genuinely trying to be principled, or loyal to your friends, you get put in really awkward situations.

Anyway, the purpose of this post is to say that if you understand exactly what I’m talking about, then try flipping it around. In other words, there are people out there whom I’ve judged in the past, attributing the worst of motives and so forth. But I bet if I saw a movie of their lives, I would be much more understanding of why they did the things that struck me as so outrageous.

Recent Comments