Paul Krugman’s Eyes Are Smiling

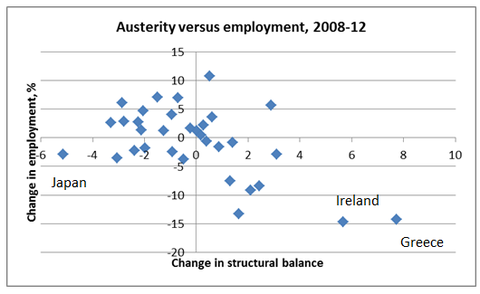

In this post, Krugman takes Marco Rubio to task for claiming that government deficits crowd out private investment. Amongst his points, Krugman produces the following scatter plot:

…and then comments, “Contractionary policy has proved contractionary.”

Wait a second. Look at that chart. Even on its own terms, it’s not nearly as obvious as Krugman makes it seem–if you take out the bottom two data points, there’s no clear pattern at all.

And what are those bottom two data points? Greece and Ireland. As we all know, the Greek government systematically lied for years about its actual deficit, in order to placate EU authorities and continue to violate their rules about fiscal responsibility. Then when the crisis struck, their bonds got hit–you know, by those “invisible” vigilantes in which Krugman doesn’t believe. So yes, the Greek economy has been performing badly the last few years, but it’s not a slam-dunk case that this is an example of why fiscal prudence is a bad thing.

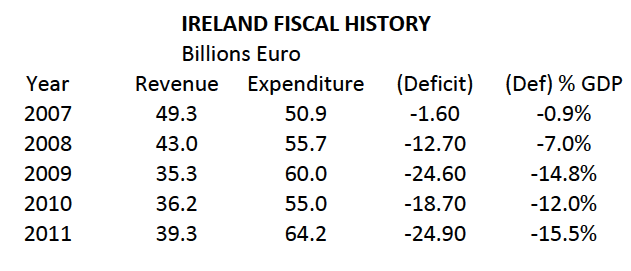

Yet the other example, Ireland, is even more ridiculous for Krugman to be using in this fashion. I have no idea what it means to say that from 2008-2012 Ireland had a “change in the structural budget balance as a percentage of potential GDP” of almost 6%, but here is what Wikipedia has to say about the expenditures, revenues, and deficits for Ireland from 2007 – 2012:

So with those numbers, you can see it’s a bit much to cite Ireland as an example of a country that eschewed Big Government Keynesian demand stimulus when the crisis struck.

In fact, I can cite a Nobel laureate who agrees with me, that the Irish bailout of its banks was a terrible idea, because it racked up too much debt:

Ireland’s bank bailout had a face commitment around 15 percent as large as the TARP — in an economy 1/100th the size of the United States. The TARP was only 5 percent of GDP; even if a large part of the money (mainly used to purchase bank equity) had been lost — which it wasn’t — it would not have been a big factor in federal debt.

There have been other losses, largely at Fannie and Freddie; but in the end the cost of financial bailouts is not an important factor in US debt and deficits. In Ireland, by contrast, it is what has made a potentially manageable debt situation catastrophic.

I’d add that the big risk in October 2008 — that the whole world financial system would freeze up — was never a concern in the Irish case.

But mainly, putting taxpayers on the hook for 5 percent of GDP is one thing; putting them on the hook for 60 or 70 percent of GDP, something quite different.

At this point, I don’t have to actually tell you which economist I’m here quoting, who was worried about the Irish government’s spending in the crisis leading to a “catastrophic” debt situation, do I?

Potpourri

==> I make a modest point about fracking and federalism.

==> Simon Lester thinks Krugman is up to no good on his post about protectionism, but I don’t really have a dog in that fight. BTW, my Krugman takedowns are still coming, I’m just digging myself out of a pile of stuff.

==> Consumers are now safe from milk that is too cheap, in Louisiana.

==> Gene Callahan explains the basic point that even if one trusts Barack Obama to only blow up the bad guys, what happens when we have a bad guy in the White House?

==> Mario Rizzo wants to raise your taxes. (But read it in context to see what he’s saying.)

==> Joe Salerno argues that the Fed is creating more asset bubbles.

==> Daniel Kuehn has no problem with minimum wage hikes, and Nick Rowe thinks economy-wide price controls might be good in the short run. I am now officially going to leave economics and go full-time into comedy.

An Odd Proposal to Tax Oil, From the CFR

In this IER post I take on a new paper (published through the Council on Foreign Relations) to impose a $50/barrel tax on crude oil. Some excerpts:

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) recently released a study by Daniel Ahn and Michael Levi showing how a new tax on oil—which would ultimately raise pump prices by $1.20/gallon—might benefit Americans. The two main reasons were: (a) right now oil is too expensive, so taxing it would help, and (b) The revenue from a new oil tax would allow the government to spend more money, thus making the economy stronger. If the reader has not yet fallen out of his or her chair, in the rest of this blog post I’ll show that I’m not making this up.

…

Step back and think about what that means. The CFR study is saying that if the government slapped a $50/barrel tax on oil, which works out to $1.20 per gallon of gasoline, and if it then used all of the revenue to increase government spending, then this would help the economy over an 8-year-period.One might ask, almost in jest, “Well if a new oil tax of 1.5% of GDP is a good idea, why not make it bigger?”

Fortunately, the CFR study does just that. In the next section, they “demonstrate” that doubling the oil tax to 3% of GDP—i.e. $100/barrel of crude, or $2.40/gallon—and using all of the revenue to fuel government spending, would make the economy grow even faster, and create more jobs, than the Variation 1 from above.

Krugman Bask

OK kids, I’m back on the job. In my absence (as I worked on a major deadline) my colleagues (1, 2, and 3) have picked up the slack, but now I’m back to keep Krugman’s toes to the fire.

However, it would help if one of you could find a good example of Krugman walking through the budget numbers to “prove” that Obama didn’t really increase the deficit. Instead, Krugman has been arguing, the apparent surge in deficits is entirely due to the major recession (which implies bigger safety net payments and lower tax receipts).

This post is close to what I mean, but there were other ones (when Krugman did a Dr. Evil “one trillion dollars!” takedown) that are better for what I need.

Israel Kirzner and the Invisible Hand

Von Pepe sent me this nice video of Israel Kirzner accepting an award (posted at Coordination Problem):

As Kirzner explains, even though he of course understands the scientific study of “spontaneous order,” nonetheless he sees the hand of God behind events.

This is yet another example of how atheists and theists can look at the same phenomenon, and walk away with opposite conclusions. Kirzner, Gene Callahan, Tom Woods, and I all have different views of God, but we all believe He exists and are awestruck at His genius in designing a social order where the natural depravity of man can be turned unwittingly into showering goodness on others. This obviously fits right in not just with Christianity, but also with Judaism; see for example Joseph’s reassurance to his brothers.

Yet I know atheists draw the opposite conclusion. Indeed, I’ve had them openly ask me things like, “Bob, you can see in your study of economics that there can be order without a designer. So why can’t you just accept that the universe has no grand purpose? It just happened.”

“The Banker” Needs to Call Me for a Lifeline

This video is ridiculous. They’re trying to simultaneously make it look like (a) the banks won’t be taxed a lot and (b) the banks will be taxed a lot.

Dean Baker vs. Dean Baker on Government Debt and Interest Rates

On Monday Dean Baker was upset that Robert Samuelson thought the two-decade Japanese experiment in stimulus policies should somehow be taken as a warning note against stimulus policies. Baker wrote:

Whether Japan’s debt is “excessive” can be debated, but it certainly does not have an excessive interest burden. Its interest burden is currently around 1.0 percent of GDP. It would be even lower if the interest paid to the central bank, and refunded to Japan’s treasury, were subtracted.

This low burden is possible because the interest rate on Japan’s debt is extremely low, with short-term debt getting near zero interest and long-term interest rates hovering near 1.0 percent. Samuelson wrongly imagines that the government would face a disaster if interest rates rose. In fact, it would be able to buy up its long-term debt at huge discounts and quickly reduce its debt to GDP ratio.

(Bond prices move inversely to interest rates, so if interest rates on 10-year treasury bonds rose to 3 percent, Japan’s central bank could buy them back for around half of their current price. There would be no real reason to do this, but it would placate the sort of ignorant people who tend to dominate economic policy debates and get obsessed about debt to GDP ratios.)

Now when I read this, I was all set to make a snarky post about me having a long-term, fixed-rate mortage, as well as a bunch of credit card debt I’m trying to pay down, and asking you guys if–per Dean Baker–I should be pining for a massive spike in interest rates.

But I don’t need to do that, I can just turn to Dean Baker who wrote on Wednesday (two days after the above):

Currently net interest rate payments are 1.4 percent of GDP. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects this will rise to 3.3 percent of GDP by 2023. This 1.9 percentage point rise in projected interest payments is by far the largest cause of projected increases in deficits over the decade. In addition, the interest refunded from the Fed to the Treasury is projected to fall by 0.3 percentage points, meaning that higher interest costs are projected to add a total of 2.2 percentage points to the deficit.

This rise is noteworthy because it is almost entirely due to higher interest rates rather than large debt, since the debt to GDP ratio is projected to be only marginally higher in 2023 than it is today. The projection of higher interest rates is in turn a projection about Federal Reserve Board policy. In other words, CBO projects that the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates over the next decade will be the main factor pushing deficits higher.

The Post somehow missed this one.

Hmm, maybe the explanation is that the people at The Post had read Baker’s blog analysis from 48 hours earlier, and thought the rise in interest rates would do wonders for the US government’s debt situation?

Recent Comments