If the New Testament Merely Teaches Us Moral Lessons, Then Standard Christianity Collapses

Gene Callahan recently had an interesting post in Biblical inerrancy. (Loosely speaking, this is the claim that the Bible is literally true because it is the inspired Word of God. Go look at the Wikipedia entry if you want to see a subtler treatment, which contrasts Biblical inerrancy with infallibility, for example.) Here’s Gene:

[T]he story of the adulteress, the one in which Jesus talks about whoever has no sin casting the first stone, does not appear in any manuscripts or in any commentary on the New Testament before about the 12th century A.D. (Bart Ehrman speculates that something like the following occurred: one scribe in reading John saw Jesus saying things about not judging others. He thought, “I know a wonderful story that’s been circulating about Jesus that illustrates that point nicely.” He then wrote the story of the adulteress in the margin. A second scribe saw that, and thought, “Gee, this guy accidentally left that part out, and then had to write it in the margin. Let me get it in the main line of the text.”) In any case, it is nearly certain that the story of the adulteress did not make it into John until after 1000 A.D.

But why should this worry me one way or the other? It is a great story that teaches an important spiritual lesson. Isn’t that what is important, rather than whether or not it was in the earliest version of John?

Generally speaking, I very much appreciate Gene’s views on religion, but on this particular issue I’ve never agreed with his nonchalance. Because my faith is different from Gene’s, knowing which part(s) of the Bible are literally true, and which may merely be exaggerations or even outright fictions that were invented by later writers, is crucial. Here’s why:

==> Most crucial, the standard Christian view is that Jesus of Nazareth was God incarnate in man. God Himself decided to walk among us, teaching and healing, and He decided to enter the world through a human woman’s womb in the form of the 100% man whom we know as Jesus of Nazareth. He performed many miracles, but His most important one was literally rising from the dead after dying on a cross. If there really wasn’t such a man–or even if there had been a really wise, kind man who left disciples who made up stories about him after his death–then standard Christianity collapses. The Christian’s hope of salvation and eternal communion with God in paradise is dashed. (Maybe we could rebuild it on a different framework; Gene believes in God, after all. But my point is, standard Christianity can’t rest on a foundation of “wonderful parables.”) See Paul in Corinthians on this matter.

==> On the story of the adulteress in particular, I am very interested to know whether this is something that actually happened, or if it’s just a fable invented by subsequent Christians (presumably acting with good intentions). One of the biggest problems with Christianity is reconciling the freedom of faith in Christ with the Law laid down through Moses. When an atheist libertarian nowadays demands to know whether I am in favor of carrying out death sentences as laid out in Deuteronomy (I am not), it’s very tidy to say, “As my Master said, let him who is without sin cast the first stone.” But I need to cite something else, if it’s not clear whether Jesus literally said that. Obviously we have no evidence that Jesus ever physically hurt someone (driving the moneychangers from the Temple being the only thing close), so I have no doubt that His example showed that we’re not supposed to kill people for sinning, but I personally was indeed disturbed when frequent commenter “Ken B.” on this blog pointed out the genuine doubt even among theologians about the story of the adulteress.

My Thoughts on Formalism in Economics

Recently many econobloggers have offered their thoughts on what is often called “mathematics in economics,” but I think is really more about formalistic model building in economics. Here’s a very interesting post that has links to some of the other people in this dispute. For my part, just some scattered observations with no necessarily overarching lesson:

==> When discussing my thoughts on the Misesian “pure time preference theory of interest,” it was very easy to communicate a key distinction–a preference for earlier goods versus a preference for earlier utility–in the language of mathematical economics; it was the discount on future utils (often denoted by beta) versus the marginal rate of substitution between a good available at time t versus t+1. In contrast, Austrians use the same phrase–“time preference”–for both concepts, which made it very difficult to get anywhere. (If you want to read more of my views on this, check out the links at this post.) So this is exactly the kind of thing that the proponents of mathematical formalism cite–there are ambiguities and imprecision with spoken language that can be alleviated with symbolic modeling.

==> But don’t take the above point to be an award of victory to the formal camp. At the crucial point–going from the formal model to the spoken-language interpretation of what the model means–the formal economists lapse into whatever they want the result to be. For example, when I was at NYU I spent a good deal of time trying to get the mainstream professors to appreciate Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of the “naive productivity theory” of interest, and to see the dangers in teaching (as they did) that “interest equals the marginal product of capital” in equilibrium. At their encouragement, I stopped saying it in words and built little models to illustrate the problem. One guy finally “saw” it and said, “Well, assume you can turn tractors into bananas one-for-one.” I am not joking; that’s how he dealt with my concerns. And then another guy told me, “Yes, I agree there is more to it than just taking the derivative of the production function…but somehow we know.”

==> Continuing in the above vein, go look at the appendix to my dissertation if you can handle it. In my mind, this was analogous to Einstein’s special relativity; I came up with a more general framework that had the mainstream “r = MPK” as a special condition case. But, so far as I can tell, I’m still the only person on Earth who thinks I’m this much of a genius. The proponents of the formal approach don’t usually stress this aspect of things: You can come up with the most brilliant model ever, which shows in crystal clear fashion how your critique of the orthodox approach is valid, but if nobody cares, and just ignores your model, then there’s not much you can do about it except whine on your personal blog for years to come.

==> Let me give another example. When Bryan Caplan chimed in to this discussion, he proved his bona fides by linking to one of his theoretical papers. It’s titled, “Standing Tiebout on his head.” Here’s the abstract:

Much of the public finance literature argues that local governments behave competitively due to residents’ ease of exit and entry. The model presented here challenges this widespread conclusion. Though it is costless to relocate to another locality, the presence of tax capitalization makes it impossible for land-owners to avoid monopolistic pricing of public services by moving; land-owners can only choose between paying the tax directly, or paying it indirectly in the form of a lower sale value for their housing if they exit. In consequence, the only real check on local governments comes through imperfectly functioning electoral channels.

Now my first reaction to the above is, “Huh? That sounds like it’s standing Tiebout on his feet. It shows that workers can indeed escape the clutches of the taxman, whereas landowners can’t, since–duh–you can’t move land out of the jurisdiction of the taxing authority. By the same token, if workers were only allowed to sell their labor in their current jurisdiction, then they wouldn’t have much scope to vote with their feet. Yet that insight hardly refutes Tiebout.”

Now maybe Bryan is actually saying something more profound than what I think he’s saying; the way to be sure would be to read his paper. The virtue of a formal model is that it would be crystal clear how he was achieving his result. However, we once again come back to the problem that the interpretation of the result is not something the model itself can give you: whether this is standing Tiebout on his head, or whether it’s an obvious extension of Tiebout, is something that we have to discuss in words, not symbols. (It’s also possible that the title is just to be provocative, and really Bryan’s claim is an empirical one on whether the immobile land effect outweighs the mobile workers effect. Again, I would have to sit down and read the paper to be sure, but even here, the crucial step would be in interpreting what his model “means” in the grand scheme of things.)

==> Austrians need to be a little careful when they make sweeping condemnations of the “unrealistic models” of their opponents. After all, when “our side” teaches comparative advantage, we use the completely unrealistic 2-good 2-country model. When we explain Menger’s theory of the origin of money, we tell simplistic stories that have no basis in history. When we explain Bohm-Bawerk’s views on capital accumulation, we often start with ludicrous Robinson Crusoe tales. And even Mises himself pounds home the fact that his “evenly rotating economy” is not only false, but internally inconsistent.

==> Last point: Until I saw it with my own eyes, I would not have believed how much the people in top-ranked economics programs are great at math, but bad at basic economics of the kind that I learned by reading op eds from Walter Williams and Thomas Sowell growing up. For example, one of our professors went through the Solow growth model and then concluded that it was a great mystery why the return to investment had been so low in the former Soviet Union, since after all their engineers trained at Western universities so they had the same production functions. (!) Our game theory professor relayed an anecdote in which all but one person (Aumann) at a game theory conference said he or she would offer “0” in the Ultimatum game, since this was the unique subgame perfect Nash equilibrium. (And just remember, these were the guys helping to design strategy during the Cold War.) I And my all-time favorite: I didn’t witness it personally, but apparently at a meeting when the United Auto Workers were trying to unionize our grad students, a guy who was really good at math in our program piped up and told the provost that NYU owned some apartment buildings, and so it could offer to give them at zero price to the grad students since it wouldn’t cost NYU anything. To repeat, this was a guy who would go on to get a PhD in economics from what was, at the time, probably ranked about 15th in the world.

Yes, There Are Indeed Two Scott Sumners

In a recent post, Scott whimsically wondered whether there were two of himself. But actually, there are, in the sense that he will hammer home a particular perspective, then apparently violate it himself. One example is that he constantly says that interest rates are a poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy, yet then points to the Fed’s raising of interest rates in 1937, and the ECB’s raise mid-crisis, to show that tighter money can cause a double dip. (Sorry can’t look up links right now.)

Recently I saw another example. One of Scott’s trademark claims is that there’s no such thing as “waiting to see” if, say, QE has worked or not; you can tell immediately based on the market’s reaction to an unexpected policy announcement. For example, here is Scott in his own words in September 2012:

I’ve also tried to convince the blogosphere of other ideas, such as “targeting the forecast” and that there is no “wait and see.” I think it’s fair to say I’ve completely failed (thus far) to make headway in that direction. Roughly 100% of the blogosphere has reacted to QE3 by discussing likely future outcomes for AD/NGDP, as if in the future we’ll learn more than we already know. I view that as akin to astrology.

Yet when it comes to recent suggestions that the Fed’s policies are hurting Indonesia, Scott says: “I’d encourage everyone to take a deep breath and let’s wait 12 to 18 months, by which time it may be easier to see what’s going on right now.” I guess we’ll ask a Sagittarius.

I Knew This Would Happen: Minimum Wage Shenanigans

Remember back when we were arguing about the minimum wage? One of the things I pointed out–here’s a post on the topic but unfortunately I can’t find myself making this specific point–is that even if you conceded that “modest” increases in the minimum wage wouldn’t lead to significant drops in employment, that that had no bearing on whether Obama’s proposed 24% increase (to $9/hour) would have an effect.

Now check this out. As you probably know, fast food workers are striking because they want the minimum wage to more than double, from its current $7.25/hour to $15.

In a story on August 29, NPR reported this:

Industry officials say a sharp increase in the minimum wage would kill jobs.

“Doubling the minimum wage is absolutely, positively going to reduce the number of jobs,” says Scott DeFife, executive vice president of policy and government affairs at the National Restaurant Association.

Yep, there’s nothing wrong with that statement at all. To my knowledge, there is not a single empirical study claiming that a doubling of the minimum wage wouldn’t lead to a reduction in employment.

And yet, Media Matters jumps in to “correct” this shocking falsehood:

Contrary to industry officials’ claims, economic studies have concluded that raising the minimum wage has no effect on employment. In a Center for Economy and Policy Research report titled “Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?” senior economist John Schmitt determined that there is “little or no employment response to modest increases in the minimum wage.” According to Schmitt, extensive research revealed that raising the minimum requirement has little or no statistically significant effects on employment at all.

Schmitt’s conclusions are supported by more than 650 economists — including Nobel Laureates and former presidents of the American Economics Association — who signed a statement affirming that increasing the minimum wage would have little or no effect on employment but would improve workers’ well-being:

We believe that a modest increase in the minimum wage would improve the well-being of low-wage workers and would not have the adverse effects that critics have claimed. In particular, we share the view the Council of Economic Advisors expressed in the 1999 Economic Report of the President that “the weight of the evidence suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage have had very little or no effect on employment.” While controversy about the precise employment effects of the minimum wage continues, research has shown that most of the beneficiaries are adults, most are female, and the vast majority are members of low-income working families.

OK, so the parts I put in underline above come from the Media Matters writer, Samantha Wyatt. In contrast, the parts in bold come from the economists when she’s literally quoting them, not “paraphrasing” them. Notice an important difference, in the context of a proposal to (more than) double the minimum wage?

We’re #75! We’re #75!

According to a new ranking of the “most influential economics blog,” Free Advice weighs in at #75. I couldn’t have done it without both of you.

I have to say, though, that I wonder about the method used here to calculate “influence.” According to the site, they use an “input output model” to generate the influence number. Yet in some cases, it’s not even close to the raw traffic ranking.

For example, LewRockwell.com is only #32 on this ranking, while Brad DeLong is #6. I’m guessing that’s because Krugman–who’s #1 in this ranking–links to DeLong all the time. If you check Alexa, LRC has a traffic ranking of 9,241, compared to DeLong’s 101,016. So that means they’re not even in the same galaxy as far as how many people actually read the sites. (I can’t figure out how to assess Krugman’s overall traffic, because Alexa is just giving me the stats for the New York Times overall. Any smart people out there who can help me out?)

Similarly, this ranking has me ahead of EconomicPolicyJournal.com, when I know full well that Wenzel gets more traffic than me. And yes, Alexa says he is ranked 66,596, compared to my 226,951.

In any event, it seems the best strategy for someone to boost himself in these “influence” rankings is to provoke links from Krugman, DeLong, and Tyler Cowen. Looks like I’ve intuited the right thing to do.

UPDATE: And oh man, ZeroHedge.com‘s Alexa ranking is 1,864. In case you don’t realize it, these things are not linear; as you move up the rankings, the amount of traffic you are getting starts rising very rapidly. So to say ZeroHedge has less influence–with an overall traffic ranking of 1,864–than DeLong with his traffic ranking of 101,016, cries out for an asterisk.

MIT Economist’s Audacious Paper on Economic Climate Models

I’ve been traveling so much I just realized I haven’t blogged about this yet. I have two IER posts summarizing some of the key points from a forthcoming paper (in the September issue of the Journal of Economic Literature) that is surprisingly scathing in its treatment of the “social cost of carbon” estimates coming out of Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs).

Now the author–Robert Pindyck of MIT–is a supporter of a carbon tax. I made sure to say that upfront in both of my articles. (I can’t speak for other groups; don’t know if they exercised such care.) So you can read this objection from Pindyck to be sure you have the full story.

Anyway, back to my two articles on Pindyck’s paper: they are here and here. Here are some excerpts:

Pindyck’s paper is titled, “Climate Change Policy: What Do the Models Tell Us?” Here is his shocking answer, contained in the abstract:

Very little. A plethora of integrated assessment models (IAMs) have been constructed and used to estimate the social cost of carbon (SCC) and evaluate alternative abatement policies. These models have crucial flaws that make them close to useless as tools for policy analysis: certain inputs (e.g. the discount rate) are arbitrary, but have huge effects on the SCC estimates the models produce; the models’ descriptions of the impact of climate change are completely ad hoc, with no theoretical or empirical foundation; and the models can tell us nothing about the most important driver of the SCC, the possibility of a catastrophic climate outcome. IAM-based analyses of climate policy create a perception of knowledge and precision, but that perception is illusory and misleading. [Bold added.]

And:

This is my favorite part of Pindyck’s paper…:

The question is how to determine the values of the parameters [used in the computer models’ damage functions]. Theory can’t help us, nor is data available that could be used to estimate or even roughly calibrate the parameters.

As a result, the choice of values for these parameters is essentially guesswork. The usual approach is to select values such that L(T) for T in the range of 2°C to 4°C is consistent with common wisdom regarding the damages that are likely to occur for small to moderate increases in temperature…Sometimes these numbers are justified by referring to the IPCC or related summary studies….But where did the IPCC get those numbers? From its own survey of several [Integrated Assessment Models]. Yes, it’s a bit circular. [Pindyck pp. 12-13, bold added.]

Pindyck’s point is so important—and so hilarious—that I want to make sure the reader understands it. There is no underlying economic theory and we have no empirical data by which to estimate the impacts on humans coming from even moderate (let alone large) increases in global temperatures. Thus when economists design computer simulations of the global climate and economy, going centuries into the future, they literally just make up relationships between hypothetical temperature increases and the corresponding percentage decrease in the global GDP. Then, in an excellent illustration of “groupthink,” the creators of these made-up damage functions justify them by pointing to third-party summaries done of their own (made-up) damage functions.

News Flash: The Non-Stupid CBO Proves DeLong Was Wrong

I am traveling all week and have to keep this short and sweet. Here’s a chronicle of what happened in yet another exchange of blogfire with my favorite Keynesians:

==> Brad DeLong said, “There are no signs in the pace of technological progress, in the level of investment…[or in several other factors–RPM]…to suggest that the path of growth of U.S. sustainable potential GDP is materially lower today than was believed back in 2007.”

==> I pointed out that even within DeLong’s own conceptual framework, he was speaking nonsense, because investment is down. Capacity is growing more slowly now, than in 2007.

==> DeLong responded that I didn’t do my homework, and Paul Krugman pointed out that the CBO does indeed take into account that investment is down, when estimating “potential GDP.”

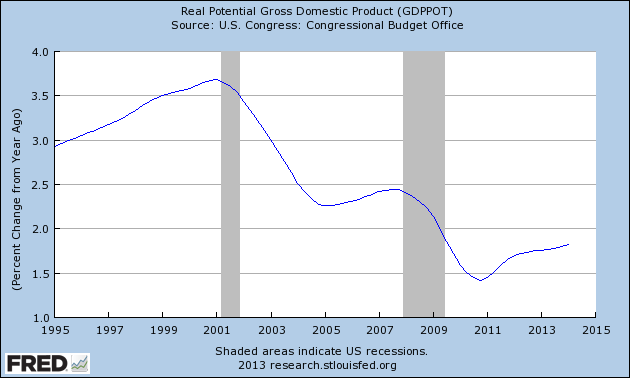

Right, exactly Dr. Krugman. And since–like I said–investment is down, so is the growth in capacity, aka “potential GDP.” Here’s the official chart showing year/year growth in real potential output, from that non-stupid organization, the CBO (so you know it’s right):

Incidentally, as I am a fount of magnanimity, I actually calibrated the above chart to end in 1q 2014. So that last data point you see is the CBO’s estimate of what the growth rate of potential GDP will be, for all of 2013.

As the above chart shows, in 2007 “real potential GDP” was growing at just under 2.5 percent per year. Yet now, the CBO predicts that in 2013 it will only grow about 1.8 percent (just eyeballing the chart). So that’s a drop of about a fourth. Is a 25% drop not “material”?

We thus have an ironic situation in which Krugman actually proved my original point. He could’ve easily titled his post, “Brad, Next Time Just Follow My Lead and Ignore Murphy–It’s Safer.”

==> Notwithstanding the above, a Keynesian onlooker says I need aloe vera (since I got burned) and an Austrian onlooker says “OMG” because I got crushed so bad. All I can say is, LOL.

Welcome to my world, kids; my life is full of episodes just like this. For those of you following me on Facebook, now you understand why I have such an odd sense of humor. It’s the only way I’ve found to preserve my sanity.

Recent Comments