Australia’s Carbon Tax: Lessons for the United States

That’s the title of my blog post summarizing the key points from Dr. Alex Robson’s new study (commissioned by IER) on Australia’s experience with a carbon tax. I don’t want to reduce your incentive to follow the link, so I won’t give any quotes here. There are some purdy graphs and everything, so it’s easy on the eyes.

Another Bang-Up Prediction From Krugman, On Employment and the Sequester

UPDATE below.

Russ Roberts reminded me of Krugman’s discussion of the sequester back in February:

But the legacy of [the Bowles/Simpson deficit commission] lives on, in the form of the “sequester,” one of the worst policy ideas in our nation’s history.

Here’s how it happened: Republicans engaged in unprecedented hostage-taking, threatening to push America into default by refusing to raise the debt ceiling unless President Obama agreed to a grand bargain on their terms. Mr. Obama, alas, didn’t stand firm; instead, he tried to buy time. And, somehow, both sides decided that the way to buy time was to create a fiscal doomsday machine that would inflict gratuitous damage on the nation through spending cuts unless a grand bargain was reached. Sure enough, there is no bargain, and the doomsday machine will go off at the end of next week.

…

So here we go. The good news is that compared with our last two self-inflicted crises, the sequester is relatively small potatoes. A failure to raise the debt ceiling would have threatened chaos in world financial markets; failure to reach a deal on the so-called fiscal cliff would have led to so much sudden austerity that we might well have plunged back into recession. The sequester, by contrast, will probably cost “only” around 700,000 jobs. [Bold added.]

Let’s see how that Krugman prediction has panned out so far:

But don’t worry, this poses no problem for Krugman, champion of “let those who make bad predictions about the economy go work at Starbucks.” For when I brought up the infamous Romer/Bernstein botched unemployment prediction, in the context of my (price) inflation bet, Krugman actually said, “In short, some predictions matter more than others.” I’m not taking him out of context; that’s what he said.

UPDATE: OK, “Joe” in the comments has convinced me that this is not necessarily a smoking gun against Krugman, since he wasn’t predicting a loss of 700,000 jobs right away. Depending on how you calculate the baseline of job growth, Krugman could understandably think that the actual results are consistent with his claim.

More Reflections on Ronald Coase

Since the transaction costs are so low, why not send you to everything I’ve seen so far:

==> David Gordon talks about Rothbard’s relation to Coase.

==> Robert Higgs gives his recollections.

==> Here’s David R. Henderson.

==> And finally, here’s Steve Landsburg.

For my own thoughts, I think Coase’s famous article “On Social Cost” is a bear to read. I almost don’t even want to assign any of it when teaching that stuff to non-economists, thinking it’s easier just to start from scratch with my own numerical examples etc. You couldn’t possibly hand that article to someone who had no idea about Coase’s perspective and say, “Good luck, that should clear up your confusion about Pigovian taxes.” Don’t get me wrong, it’s extremely important, I’m just saying you need someone to walk you through it.

I’m sorry but someone has to say it.

UPDATE: Oh here’s Daniel Kuehn on Coase as well, although (as he said more explicitly in this post) Daniel is saying, “Nobody believes in the naive Coase theorem, why do his fans keep claiming that?” and then follows with, “I believe in the naive Coase theorem, it is really interesting.” (Not exact quotes of course.)

UPDATE #2: He was so quick out of the gate, I hadn’t even caught this Peter Klein post on Coase.

Potpourri

==> Pete Boettke has a nice post on Ronald Coase. BTW, Pete alludes to an episode where William Baumol “got confused” on a basic economic principle. Does anyone have the details?

==> Jonathan Catalan digs up an interesting quotation from Keynes about mathematical economics.

==> This investment firm (I have no relationship with them, at least not yet…) explicitly endorses Austrian economics.

==> The voracious von Pepe follows several blogs, and alerts me to John Taylor who says this about the Jackson Hole conference:

The first paper was by Bob Hall, my colleague at Stanford. It argued that neither quantitative easing nor forward guidance was effective, or as he put it, “Both quantitative easing and forward guidance, as implemented by the Fed, are obviously weak instruments.” He went even further saying, in reference to the large increase in reserves to finance quantitative easing, that “An expansion of reserves contracts the economy,” in the current situation when interest is paid on reserves. He is skeptical of forward guidance because he does not think promising to deviate from a policy rule with extra low interest rates in the future is credible. It’s “hard to accomplish.”

Bob he also warned that nominal GDP targeting had serious problems, referring to his research of 20 years ago with Greg Mankiw. And instead of raising the target for inflation, going forward he argued that central bankers should focus on requiring more capital at banks and more rigorous stress testing.

==> I’m way late on this, but here’s a HuffPo piece praising Ludwig von Mises.

==> John Tamny reviews Mark Spitznagel’s forthcoming book, The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World. Note: I did a lot of consulting for Spitznagel’s book. Mark is a serious student of Austrian economics. We literally spent hours arguing/discussing Bohm-Bawerk. I’m not saying every Austrian will love the book, and I don’t even agree with everything in it, but by no means can you dismiss Spitznagel as just throwing on the label.

==> Here’s an interesting blog post from climate scientists Pat Michaels and Chip Knappenberger on the forthcoming IPCC report, and how the editors are dealing with the awkward trends in the published literature.

==> I think part of the reason Austrians are so skeptical of economists using regression analyses etc. is that the conclusions are so often interventionist. In order to get a full and balanced perspective, listen to Russ Roberts’ great interview with Lee Ohanian. Ohanian is a UCLA economist with a very supply-side, anti-Keynesian perspective on both the Great Depression and current recession. To hear him talk about these things in neoclassical terms will be a good way to refine your views on mainstream vs. Austrian methods. If nothing else, it’s good to hear a solid mainstream guy confidently say the opposite of the Krugman line, using the same type of techniques, to avoid giving outsiders the impression that if you try to do something in a mathematical model that gets published in a “prestigious” journal, then Krugman ends up being right. That is exactly the impression Krugman et al. want to give to the general public in methodological debates, so it’s nice to find examples of no-nonsense guys like Ohanian illustrating the opposite.

More on Mathematical Economic Modeling

Alex Tabarrok heaps praise upon “Quantitative Economics,” a new online text. Here is part of its description:

This website contains a sequence of lectures on economic modeling, focusing on the use of programming and computers for both problem solving and building intuition. The primary programming language used in the lecture series is Python, a general purpose, open source programming language with excellent scientific libraries.

…

If you work through the majority of the course and do the exercises, you will learn* how to analyze a number of fundamental economic problems, from job search and neighborhood selection to optimal fiscal policy

*the core of the Python programming language, including the main scientific libraries

*good programming style

*how to work with modern software development tools such as debuggers and version control

*a number of mathematical topics central to economic modeling, such as

1) dynamic programming

2) finite and continuous Markov chains

3) filtering and state space models

4) Fourier transforms and spectral analysis

Look, I enjoyed studying Markov chains as much as the next guy in grad school–actually I think the guy sitting next to me in class hated them–but I think the above is a perfect illustration of the problem with modern, mathematical economics. The world is not stuck in a terrible recession right now, because too few people understand Fourier transforms.

There Is Only One Body of Economic Law: Mises Has Spoken

I just typed in this block quotation from page 68 (Scholar’s Edition) of Human Action:

The domain of historical understanding is exclusively the elucidation of those problems which cannot be entirely elucidated by the nonhistorical sciences. [The historian’s understanding] must never contradict the theories developed by the nonhistorical sciences. [Historical understanding] can never do anything but…establish the fact that people were motivated by certain ideas, aimed at certain ends, and applied certain means for the attainment of these ends, and…assign to the various historical factors their relevance…Understanding does not entitle the modern historian to assert that exorcism ever was an appropriate means to cure sick cows. Neither does it permit him to maintain that an economic law was not valid in ancient Rome or in the empire of the Incas.

I love it when Mises gets rough with the reader.

Yet More Sumner Sleight-of-Hand

Here’s a good one. Recently John Quiggin updated a post in response to objections from Market Monetarists, because he had said (initially) that nominal interest rates were a good indicator of the looseness or tightness of monetary policy. The Market Monetarists said that the standard view was that real interest rates were a better indicator, and Quiggin agreed.

Then Scott Sumner wrote a post entitled, “Real interest rates are not much better.” He made some decent points about the theoretical difficulties in equating “low real interest rates” with “easy money,” and “high real interest rates” with “tight money.” OK fine.

But then look how Scott delivered his finishing move:

Quiggin seems to think that MMs [Market Monetarists] are sort of oddballs. OK, but what does he make of the Volcker disinflation?

1980:3 to 1981:3: NGDP growth = 14.0%

1981:3 to 1982:3: NGDP growth = 3.2%

Meanwhile nominal interest rates on 3 month T-bills fell from 16.3% in May 1981 to 7.71% in October 1982. These data are quite similar to the Australian episode considered by Quiggin. If we use his criterion for easy money then America’s most famous tight money policy since the Great Depression was actually an expansionary monetary policy.

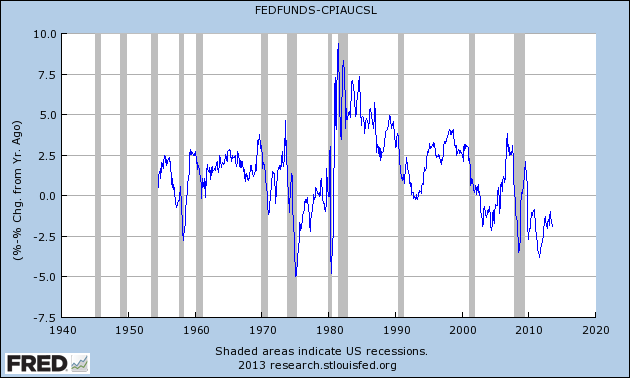

Hang on though: Are we talking about Quiggin’s updated criterion? Because if you use real interest rates–which for our purposes I generate in FRED by taking the effective funds rate minus the year/year percentage change in CPI–you get this:

So yep, the “most famous tight money policy since the Great Depression” was associated with at least an 8-percentage-point spike in the real effective fed funds rate, which also happened to be the highest real rate (using the proxy I whipped up here for this blog post) during the 60 or so years that FRED can display for us.

Obviously, I haven’t here blown up Scott’s world, but it’s odd that he points to the best example of tight money==>high real interest rates on record, as evidence that real interest rates are a poor guide to the stance of monetary policy.

Potpourri

Some various YouTube links for you:

==> FEE president Larry Reed’s “Seven Principles of Sound Public Policy.” This is a talk that he’s been giving for years (I believe).

==> Louis CK versus Jay Leno. I was actually surprised by how well Leno stood up against the man who is, in my opinion, the world’s greatest living standup comedian.

==> I know it’s ridiculous, but what the heck: The original starship Enterprise encounters Miley Cyrus.

And perhaps more out-of-the-box and entertaining than any of the above:

==> Nick Rowe wonders how he could get an economy irreversibly stuck IN a liquidity trap. (This is kind of like how I used to think about how I could steal from the grocery store where I worked, when I was a cashier.)

Recent Comments