So This Is What It Feels Like to Be a Square

All summer I have been dying to take my 8-year-old to a movie, but a bunch of obvious ones (Superman, Wolverine, etc.) were PG-13. So I was happy that I was able to take him to see Percy Jackson today–a series of which I knew nothing.

I was a little concerned when I looked up showtimes and saw the tagline for the film “In Demigods We Trust.” Then I was really uncomfortable in the opening moments when one character is apparently cursed by Zeus to never be able to drink wine (since it instantly turns to water when he pours it), and he says something like, “Now the Christians have a god who can do the reverse–that’s a god!”

I realize some of our atheist friends reading this will say, “Exactly Bob! Your beliefs are just as silly as Greek mythology.” OK, but since you agree that’s how the humor works, you can see my I wasn’t sure how I felt with my son sitting in the theater next to me.

It’s hard for me to put my finger on, but there was just something about this particular movie that seemed dubious to me, in a way that I never got from, say, Harry Potter (let alone Lord of the Rings). So it’s not that I have a problem with fantasy as a general rule, there was just something about this movie that I couldn’t shake until the cameo by Nathan Fillion (of Firefly fame).

Discuss.

DeLong Sees Nothing In the Investment Data That Would Slow Capacity Growth

[UPDATE below.]

Brad DeLong has this habit where he makes it look as if he’s walked through several different strands of evidence, and they all come down squarely on the position he agreed with at the start of his investigation–even though some of the evidence obviously cuts the other way. It’s like we’re arguing over whether the Beatles ever released goofy songs, and he says, “I have considered John, Paul, George, and Ringo, and see no reason to support your wild accusation.”

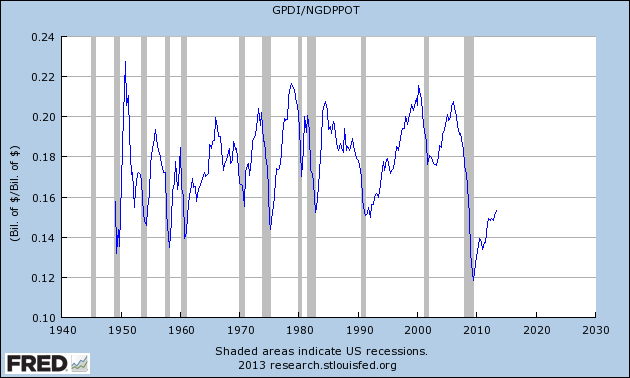

Case in point: In his most recent post, DeLong is baffled that the Fed is still gung-ho about tapering later this year. Here’s DeLong, who first posts this chart and then comments:

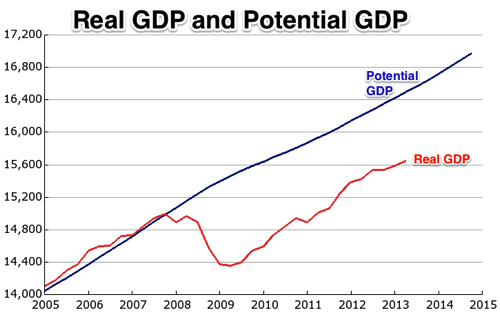

There are no signs in the pace of technological progress, in the level of investment, in the pace at which the American labor force educates itself, in measures of capacity utilization, in signs of upward wage pressure due to labor quality bottlenecks, or in surging commodity prices due to supply bottlenecks to suggest that the path of growth of U.S. sustainable potential GDP is materially lower today than was believed back in 2007. [Bold added.]

Now I could quibble with all of those “indicators,” incidentally, because according to DeLong’s own framework, we’re well below potential GDP. So the fact that, say, wages aren’t rising rapidly, doesn’t mean that potential GDP is growing as before; even if potential GDP growth had sharply decelerated in 2008, the “real GDP” line could still be well below it, meaning you would see the weak pressure on wages that we are currently seeing. (Again, I’m doing this whole post within DeLong’s framework, just to show he’s making a non sequitur even on his own terms.)

But the most egregious claim above is that there’s nothing “in the level of investment…to suggest that the path of growth of U.S. sustainable potential GDP is materially lower today than was believed back in 2007.”

Oh really? Here’s the official government statistics showing gross private domestic investment as a percentage of potential GDP. To keep potential GDP chugging along at its previous pace, you’d think GPDI should stay about the same percentage as it was from 2005-2007. But this is what actually happened:

Incidentally, I’m not purposely loading the deck against DeLong by only including private domestic investment; FRED doesn’t seem to have a single series adding government and private investment spending. But, I hardly think DeLong is able to claim that the above chart is more than offset by the huge surge in government investment spending (at federal, state, and local levels) from 2008 – present, what with the Republicans’ vicious austerity and all.

So not only are the Austrians (and Larry Summers in the occasional op ed) the only ones who think the composition of investment spending is important for sustainable growth, but apparently we’re the only ones who think going from 23% down to 15% of total potential devoted to investment, might slow down the growth of potential output.

UPDATE: In light of DeLong’s further commentary on this topic, I now think he didn’t mean that the rate of growth of potential GDP is not materially lower today, than in 2007. (It’s about 25% lower, according to the CBO estimate.) Rather, DeLong was saying that the (slower) growth in potential GDP since 2007, has not rendered its current level materially lower than people would have believed, back in 2007.

This is still very wrong, in my view. According to the CBO’s figures–which I believe are the source of the graph DeLong himself provided in his post above–the 2q2013 level of potential GDP is about 3.6% lower than it would have been, had potential GDP grown at the same rate from 4q2007 onward, as it did from 4q2006 through 4q2007. I imagine if, say, employment today were 3.6% lower than it would be in the absence of the sequester, that DeLong would not dismiss it as an irrelevant difference.

All of the above discussion can be seen in its sarcastic and puerile detail in the comments of this Daniel Kuehn post.

Potpourri

==> The other day I had a deadline, so naturally I ended up watching the SNL auditions of both Phil Hartman and John Belushi. The former impressed me much more than the latter. Hartman had a very unique style.

==> If you took away my interest in karaoke, and forced me to teach at a university and publish only academic articles, in 30 years I’d like to think I’d be Nick Rowe.

==> 2013 is a record low year for US tornadoes. You might be tempted to laugh at the climate alarmists, but keep in mind that sharks slow down the funnel clouds.

==> So now, not only do the Keynesians say, “We’re not Weimar Germany!” but we’ve actually got Noah Smith saying:

To see that inflation doesn’t reduce your real wage, just think about Weimar Germany. Prices went up by a factor of one trillion. But people did not starve en masse as a result. Remember that guy with the wheelbarrow full of cash, going to buy bread? HOW DO YOU THINK HE GOT HIS HANDS ON A WHEELBARROW OF CASH IN THE FIRST PLACE? The answer: That was not his life’s savings. He did not sell the family farm. He had a wheelbarrow full of cash because as prices skyrocketed, wages skyrocketed too! [Bold in original.]

Now you might ask, “Noah, if workers are running to and fro with wheelbarrows, won’t that reduce the productivity of their labor? How could their real wages not take a hit?”

But don’t worry, Noah covers that type of thing at the end of his post, but conceding that yes, (price) inflation carries a “nuisance cost.”

And there’s this:

And remember that today’s government debt is tomorrow’s taxes. Inflation therefore reduces the size of your future taxes. Inflation is a future tax cut! Remember, inflation means the value of a U.S. dollar goes down. But the dollar value of the debt does not change. So inflation allows you to pay off your share of the government debt with “funny money”! Awesome, right?

So I think I can now summarize the Keynesian perspective on (price) inflation, at least from the main bloggers I read and discuss here at Free Advice:

(1a) A higher target for (price) inflation will let the Fed reduce real interest rates and boost economic growth.

(1b) It is a myth put out by Austrian trolls that a higher inflation target will reduce the return to savers. Only if inflation is unexpected can that happen. If it’s expected, they will raise their nominal interest rate demands accordingly.

(2a) There is downward wage inflexibility. That’s why a higher inflation target will alleviate unemployment.

(2b) It is a myth put out by Austrian trolls that a higher inflation target will reduce real wages. Workers will raise their nominal wage demands accordingly.

(3a) Right-wingers are idiots for thinking the national debt can make us poorer. We owe it to ourselves, morons.

(3b) One of the benefits of a higher inflation target is that it will reduce the national debt and make us richer.

See the Knots the Federal Government Is In, Regarding “Social Cost of Carbon”

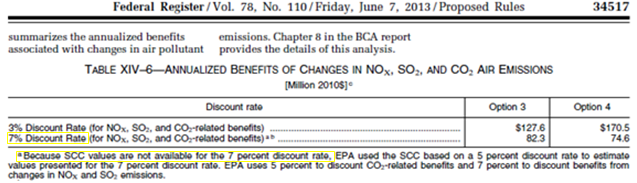

This is pretty funny. In my Senate testimony one of the key points I made was that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines state that federal agencies are supposed to do cost/benefit calculations using both a 3% and a 7% discount rate. Yet the Obama Administration Working Group only used 3% and 5% when estimating the “social cost of carbon.” My conjecture was that they avoided the 7% figure since it would show a SCC close to $0/ton, if not negative, making it awkward to clamor for immediate action to stop the catastrophe brewing before our very eyes.

To see just how serious a pickle they are in, consider EPA’s discussion of a proposed regulation on steam electric power plants. Look at this shot of a table summarizing their results:

See the part in yellow? The EPA is dutifully following Executive Branch guidelines, as laid out by the OMB. They are reporting the estimated benefits of the proposed rule at both a 3% and 7% rate. Yet, since one component of the benefits is the reduction in CO2, they have to include a footnote explaining that actually, they will be plugging in the number for a 5% discount rate, since the social cost of carbon (SCC) at a 7% rate is “not available.” (Note that the modeled benefits from reducing NOx and SO2 aren’t about climate change, but are considered direct health hazards. That’s why computing their harms–and the corresponding benefits from reductions–doesn’t do anything screwy going from 5% to 7% discount rates, as does the “social cost of carbon” since climate change is actually beneficial, according to the government’s own suite of models, for the next few decades.)

I hope this underscores just how screwy this is. From now on, federal agencies will have to include footnotes in all of their cost/benefit tables, since the Working Group explicitly chose not to estimate the number that they are all required to plug into their calculations.

To be crystal clear: The Working Group ignored the OMB guidelines, but at least reported accurately on their number: They said it was a 5% rate when giving those figures. Yet the EPA rule above, and others like it from now on, will be reporting the benefits of various rules at the “7%” rate while including the social benefits of CO2 emission reductions at the 5% rate. In other words, they are literally plugging in the wrong number; they have no choice.

Interesting Narrative on the Heliocentric Theory vs. the Church

In a recent offhand remark, George Selgin criticized certain Austrians’ thinking on banking as being akin to “theologians bungling their cosmology” six centuries ago. I asked if George actually had particular theologians in mind.

George sent me this link, which does indeed have quotes from heavy-hitting theologians (including Martin Luther and John Calvin) that are embarrassingly confident in their denunciations of the Copernican theory. I have just two remarks on this link:

(1) It was interesting to see the scriptural evidence people used to defend the geocentric (i.e. Earth at the center) model. For example, in a famous scene Joshua commands the sun to stand still. In retrospect, this really doesn’t clinch the geocentric case, since even today we say things like, “The sun rises in the east and sets in the west,” even though presumably everyone nowadays understands what’s actually going on.

According to the author, one of the most popular scriptural references is Psalm 93:

93 The Lord reigns, He is clothed with majesty;

The Lord is clothed,

He has girded Himself with strength.

Surely the world is established, so that it cannot be moved.

2 Your throne is established from of old;

You are from everlasting.

Again, I still have no problem saying I “believe in the Bible as the Word of God,” even though I endorse the heliocentric model of the solar system.

Selgin et al.’s point is well taken, of course: These theological thinkers were sure that the earth wasn’t moving around the sun–I mean, how could it be? Just use your senses!–and then, regrettably for those who believe secularist science misses a lot of important truths, these theologians then latched onto portions of scripture to “prove” their case which really didn’t prove it at all.

(2) Another interesting feature of this history is how Copernicus himself seems to have been a humble man of faith. On his tombstone he didn’t list any of his scientific achievements:

[O]n his tombstone was placed no record of his lifelong labours, no mention of his great discovery; but there was graven upon it simply a prayer: “I ask not the grace accorded to Paul; not that given to Peter; give me only the favour which Thou didst show to the thief on the cross.” Not till thirty years after did a friend dare write on his tombstone a memorial of his discovery.

Andrew White, the author of this account–which is hardly neutral in its stance, as the title is A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom–thinks the above is evidence that Copernicus feared desecration of his corpse by Church officials. I would think it rather reflects the fact that he is humble. He might not even have appreciated what his friend did.

Then, in an extra twist of irony for those trying to cast this as a battle of religion versus science, notice this interesting anecdote:

Herein was fulfilled one of the most touching of prophecies. Years before, the opponents of Copernicus had said to him, “If your doctrines were true, Venus would show phases like the moon.” Copernicus answered: “You are right; I know not what to say; but God is good, and will in time find an answer to this objection.” The God-given answer came when, in 1611, the rude telescope of Galileo showed the phases of Venus.

Look, I don’t want to make too much of this; I’m not trying to excuse the heavy-handedness, let alone literal persecutions, carried out in the name of Christ over the centuries. But look at that “most touching of prophecies” again. The critics of Copernicus had come up with a perfectly reasonable objection: They were saying that if his heliocentric theory were true, then it made falsifiable predictions that–according to the tools they had at the time–were wrong.

Copernicus didn’t say, “Well, our observations fall within the bounds of my 95% confidence interval, and I think with improvements in our instruments I will eventually be vindicated.”

Nope, he said he believed this objection would be answered because “God is good.”

So this is not quite the tale of secular science versus rigid theologians that Andrew White (and George Selgin) want to make it. Alas, the medieval Church did some things that horrify me, and alas, there are plenty of first-rate scientists throughout the ages who believed in God. The truth is complicated.

Potpourri

==> Totally off-topic, but I would change my gender if I could be Christina Bianco.

==> Nick Rowe strikes back on the definition of “inflation.” I know this isn’t the point Nick was making–and I don’t even disagree necessarily with anything in his post–but let me say this: If we let Scott Sumner get away with calling Fed policy since 2008 “the tightest since the Hoover Administration” because it doesn’t make NGDP grow enough for his liking, then I think we’ve blinded ourselves to the ability to even tell what is happening. Like I’ve said before, that would be like quantifying how much of a drug you’ve put into somebody by checking his heart rate (rather than measuring the volume of the liquid injected).

==> Imagine that? If you raise the total costs of hiring full-time workers (through ObamaCare), then the demand goes down. I don’t understand; there’s a liquidity trap and everything right now.

==> David R. Henderson screws up but shakes it off.

==> Tom Woods gets to interview Pat Buchanan. It’s a good thing they didn’t let me guest-host, since I could not have restrained myself from saying, “What number am I thinking of? Pat Buchanan!”

Two Sumner Posts That I Thoroughly Enjoyed

In this post, Scott hits something that I have been pointing out myself:

So let’s review the past year:

1. Keynesians warned us that it would be a huge mistake to adopt fiscal austerity in America. It would cut growth sharply. Mark Sadowski has the details.

2. The “Laffer wing” of the Keynesian movement predicts the damage to growth will be so great that the deficit might not even decline.

3. Then we find Congress does the austerity, despite the advice of the Keynesians.

4. Job growth continues in 2013 at almost exactly the same pace as in 2012. The tax revenues pour in.

5. The budget deficit gets much smaller.

And how do the Keynesians react to all this? They say “I told you so.” There was never any reason to worry about the big bad deficit. It’s coming down very fast “on its own.” Yes, if by “on its own” you mean that the evil GOP forced eurozone-style austerity on the US, and the Fed offset the effects on NGDP (unlike the ECB.)

And in this single post–which is full of irony–Scott has ensured that he will never, ever, be confirmed as Fed chairman. Phew!

Even Krugman Doesn’t Believe Krugman on Hayek

In this post, I walked through just how absurd it was when Paul Krugman recently said “…back in the 30s nobody except Hayek would have considered his views a serious rival to those of Keynes…”

What’s funny is that Krugman himself blew up that silly claim two days later, without even realizing it, in a contradictory (or at least Kontradictory) post making fun of those nutty Austrians:

Still thinking about the Bloomberg Businessweek interview with Rand Paul, in which he nominated Milton Friedman’s corpse for Fed chairman. Before learning that Friedman was dead, Paul did concede that he wasn’t an Austrian. But I’ll bet he had no idea about the extent to which Friedman really, really wasn’t an Austrian.

In his “Comments on the critics” (of his Monetary Framework) Friedman described the “London School (really Austrian) view”

[MILTON FRIEDMAN:] that the depression was an inevitable result of the prior boom, that it was deepened by the attempts to prevent prices and wages from falling and firms from going bankrupt, that the monetary authorities had brought on the depression by inflationary policies before the crash and had prolonged it by “easy money” policies thereafter; that the only sound policy was to let the depression run its course, bring down money costs, and eliminate weak and unsound firms.

and dubbed this view an “atrophied and rigid caricature” of the quantity theory. The Chicago School, he claimed, never believed in such nonsense.

I put the important part in bold above. Do you see the significance? In his zeal to rip Hayek, Krugman is admitting that Hayek spoke for the London School as well as the Austrian economists. So, unless Hayek’s mom was the only other person in the econ faculty, I think we can safely declare that Krugman (and his apologist, Kevin Donoghue) are wrong about Hayek’s influence at the time.

Moreover, von Pepe in the comments pointed out yet another inconsistency in Krugman’s beef against Hayek’s (seemingly) liquidationist writings of the early 1930s (with mild edits from me for clarity/typos):

[T]his is why I get frustrated with arguments that the Austrians were wrong or caused the Great Depression:

1. Hayek was irrelevant in the ’20s and ’30s; no one took him seriously. He was not even a footnote to Keynes.

2. Hayek’s advice was followed religiously to liquidate everything and Hayek only allowed medium-level deficit spending. If he had allowed bigger deficits, no Great Depression.

3. Hayek’s monetary policy caused the Depression–yet no one even paid attention to him.

4. Sticky wages were a problem. Hayek thought if you let the market adjust it would fix many problems. But, AD people thought that keeping wages high would get us going: AD, AD, AD…

So, we did the opposite of Hayek’s theory–Hayek’s fault…

Recent Comments