We Need Your Help in Standing Up to the Mighty Krugman

EDIT: I’m all set, thanks everyone!

I would like to buy up to 2 hours of someone’s time to do some research for the next episode of Contra Krugman. The only hitch is that I need your results by 9am Eastern time tomorrow morning (i.e. Wednesday Dec. 20). I’ll PayPal you $20 per hour.

Ideally you would have a NYT subscription, because you might run into issues of not being able to access his stuff after your free trial expires.

If you’re interested, please email me at rpm@consultingbyrpm.com. If multiple people apply, I’ll just pick the first one in my inbox.

More on Unemployment Duration

Earlier I had posted a graph showing the *mean* duration of unemployment spells, and I used it to buttress my claims that something was screwy with the labor market. But in the comments Kevin Erdmann seemed to be disagreeing with me when he wrote:

I think most of this is due to the extreme extended unemployment insurance policy that was put in effect during the crisis. It’s hilarious that people tried to argue that extended UEI didn’t increase unemployment. It’s so extreme and it’s specific to the duration range that was covered by insurance. Interesting that some of that remains. I think the remaining average is greatly influenced by a small contingent of workers with VERY long durations. I bet the median figure is back to normal.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UEMPMED#

Yep. Close. I think most of the remaining drift up is demographic. Older workers tend to have lower UE but longer durations. Again, you can get age specific numbers from [BLS], and those will be more stable. [Bold added by RPM.]

OK, so even on his own terms, that wouldn’t blow up the “structuralist” story, to say that the mean (but not median) unemployment duration shot way way up, because there were a segment of workers–how many? 2 million?–who just got ejected from employment prospects after the housing bust.

But is Kevin right when he says that if we look at *median* duration, we’re “back to normal”?

Not at all:

So I understand why Kevin eyeballed that and thought we were out of the woods; it’s a natural reaction to that graph. But it’s wrong.

Look more closely. Yes, the median duration has fallen way down, but its current level is still higher than it was, going back to the 1960s, except for two brief periods, one of which was the depths of the early 1980s recession that at the time was the worst since the Great Depression. So no, we are not at all “back to normal” or “Close” as he says, specifically.

(If you slide the right bar to the left, so that the x-axis ends in 2008, then the y-axis rescales and you can see how high 9.6 weeks is, historically speaking. It just seems pretty low when the whole y-axis gets crunched down to showcase the incredible awfulness of the Great Recession.)

Now let’s try something else. I’m going to plot the same series–median duration of unemployment–against the unemployment rate:

Now do you see it, boys and girls? Something is screwed up with the labor force market. The official unemployment rate is masking deep wounds, and the “structuralist” story makes a lot more sense than “there wasn’t enough spending” story.

P.S. Kevin and I agree about extending unemployment benefits. Where we disagree is in him thinking we’re back to (close to) normal on unemployment duration, or that this doesn’t bear on the structuralist vs. demand interpretations. (Note that Krugman mocked the if-you-pay-people-not-to-work-then-they-won’t-work idea at the time.)

Krugman on Paul Ryan Bask

For newcomers, on this blog a “bask” is a blog ask. (I don’t beg so I don’t do blegs.)

In this Vox interview, Krugman says: “Believe it or not, Paul Ryan’s original proposal was a sensible proposal, which had backing from Democratic-leaning economists as well. If it were actually on the table, I probably would be saying, “Yeah, I’m in favor of this as long as it’s deficit-neutral,” but the actual proposal looks nothing like that.”

Does anyone know what Krugman is referring to? I’d like to go to his blog at the time Ryan released this “original proposal” to see what Krugman’s reaction was, but I’m not sure what he evens means by this? I’ve asked someone more wonky than I, and he didn’t know either. Thoughts?

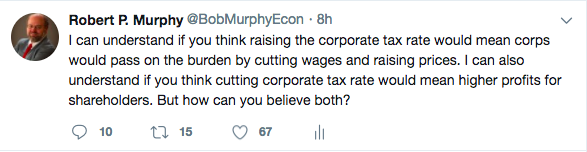

An Argument About Corporate Consistency

Inspired by this Sumner post, I recently tweeted:

Someone chimed in to say I was an idiot, and that he could obviously reconcile those two propositions.

So I came back and said (paraphrasing), “OK, so if the government keeps cycling back and forth, first raising the corporate tax rate 5 percentages points then cutting it 5 points then raising it 5 points etc., you think prices will go to infinity and wages will go to zero?”

I haven’t checked back yet but I’m pretty sure there won’t be an apology waiting for me.

The Superlative Jesus, Part 2

In last Sunday’s post I quoted this challenge:

“Why should we place Christ at the top and summit of the human race? Was he kinder, more forgiving, more self-sacrificing than Buddha? Was he wiser, did he meet death with more perfect calmness, than Socrates? Was he more patient, more charitable, than Epictetus? Was he a greater philosopher, a deeper thinker, than Epicurus? In what respect was he the superior of Zoroaster? Was he gentler than Lao-tsze, more universal than Confucius? Were his ideas of human rights and duties superior to those of Zeno? Did he express grander truths than Cicero? Was his mind subtler than Spinoza’s? Was his brain equal to Kepler’s or Newton’s? Was he grander in death – a sublimer martyr than Bruno? Was he in intelligence, in the force and beauty of expression, in breadth and scope of thought, in wealth of illustration, in aptness of comparison, in knowledge of the human brain and heart, of all passions, hopes and fears, the equal of Shakespeare, the greatest of the human race?” — Robert Ingersoll

In the last post, I took on Ingersoll’s implication that Buddha was more forgiving and self-sacrificing than Jesus. I argued that he wasn’t, simply because Jesus’ mercy and in particular self-sacrifice is just about the most you could logically imagine of a person.

Keshav (who by the way is an extraordinary guy–look at his comments on this Gene Callahan blog post) helped me out by explaining why Ingersoll presumably thought Buddha could hold his own in this respect. Here’s Keshav summarizing:

1. Buddha was opposed to the animal sacrifices that Hindus were doing at the time, and once when he saw an animal about to be killed in an animal sacrifice, he asked to be killed in its place.

2. Buddha was originally a prince who lived a sheltered life in the palace, but once he went out and saw the suffering associated with birth, death, disease, and old age, he gave up all royal luxuries and went in search of a cure for all the world’s suffering.

3. He joined a Jain monastery whose focus was self-mortification, in the hope that inflicting great pain upon himself might lead him to achieve a realization of how to end the world’s suffering.

4. He sat under a tree giving up food, water, etc. and meditated, in the hope of achieving a realization of how to end the world’s suffering.

5. He asked that all the sins of not only mankind but all living beings accrue to him instead.

6. Buddha believed he’d found the end to suffering, and he could have just adopted the solution for himself and ended all of his suffering, but he decided to forgo his happiness for the sake of alleviating the suffering of others.

7. Once he was walking through a forest when he met a robber who said “I’ve come to take all your belongings.” He said “OK, take them.” Then the robber said “No, but I’m also going to cut off your little finger, because I make a garland out of the little fingers of all my victims.” Buddha said “OK, take it.” The robber said “No, you don’t understand, I’m not just going to take your little finger, I’m going to take your life.” Buddha said, “OK, take it.”

8. Once someone gave Buddha poisoned pork. Buddha accepted it with equanimity and ate it. He immediately fell violently ill, but he told his disciples to tell the person who gave it to him that the pork was excellent and that he would achieve great rewards in the afterlife for serving the last meal of Buddha. Buddha died shortly thereafter.

In a related vein, RPLong said this:

Buddha is said to have attained Nirvana, which is basically analogous to the kind of total universal comprehension you were talking about in your previous post, Bob. In a manner of speaking, Buddha went to the Buddhist equivalent of Christian heaven. Note that some Buddhist monks of ages past have committed ritual suicide when they believed they had achieved this. Instead, Gautama Buddha spent the rest of his life traveling around and teaching people despite knowing that they would never fully understand.

He gave up heaven, in a way, to share his knowledge with the world. That’s an enormous sacrifice. Now, you could argue that it wasn’t as big a sacrifice because it didn’t involve torture and crucifixion, but is that really the standard we want to set for self-sacrifice? It only really counts if it’s physically painful? I don’t think so.

OK, so these are great anecdotes. I don’t want to come off like I’m saying, “Pshaw, Jesus is the only wise and self-sacrificing person.”

Even so, if we are going to allow the supernatural, then Jesus has Buddha beat here too. According to the Bible, Jesus was literally God, a King who humbled Himself to become a poor man born in a manger in order to (be tortured to death and) save us. According to the Apostles’ Creed, after the crucifixion Jesus plunged into the depths of hell to conquer death on our behalf. So if you’re going to allow that Buddha achieved Nirvana and then walked back from it in order to share it with us, that’s fine (and cool), but it doesn’t top the Christian narrative.

Now just to clarify, for the remainder of these posts, I’m not going to invoke anything supernatural. Obviously, on its own terms, the accounts of Jesus establish that there is no greater name. But I took Ingersoll’s challenge to be directed at people like Dan, who had said (words to the effect) that the accounts of how Jesus conducted himself as a man, show him to be the greatest man who ever lived and a role model for even secular people.

Before ending this post, let me address two more things:

First, look again at what Keshav wrote about Buddha: “Once someone gave Buddha poisoned pork. Buddha accepted it with equanimity and ate it. He immediately fell violently ill, but he told his disciples to tell the person who gave it to him that the pork was excellent…”

This is a neat story, but it underscores why I rejected Buddhism and returned fully to Christianity in grad school. Recall I had been a “devout atheist,” then went through some experiences and trains of thought that made me believe in a God. However, I was wide open at first, and I started reading about Buddha. (I can’t remember if I explored Confucius.)

I could see there was a lot of wisdom in the Buddhist approach, but I finally concluded something like this: The Buddhists teach you to deal with apparent evil by telling yourself that for all you know, maybe it’s good. The Christians teach you to deal with evil by having faith that God will use it achieve good. Those sound similar but they’re actually radically different, and it’s why I decided Jesus was my leader, not Buddha.

Finally, in the comments of the first post, Capt. Parker brought up C.S. Lewis’ famous trilemma, by which Jesus was either Lord, liar, or lunatic. In other words, C.S. Lewis rejected as faux homage when people said, “Oh I am not religious, but I appreciate that Jesus was a great moral teacher.” Lewis said that if you actually study the gospel accounts–especially if you understand the basics of Judaism–then it’s clear Jesus was saying He was God. And so you can’t pick and choose his sayings in order to dodge the question, according to Lewis.

So yes, I think that’s right, but even so, the first step is to get people to agree that in terms of Jesus teaching us about human nature and how to conduct ourselves in this bewildering life, he has the key. And once you admit that, it will be harder for you to resist the implications of that, when you consider the other claims Jesus made.

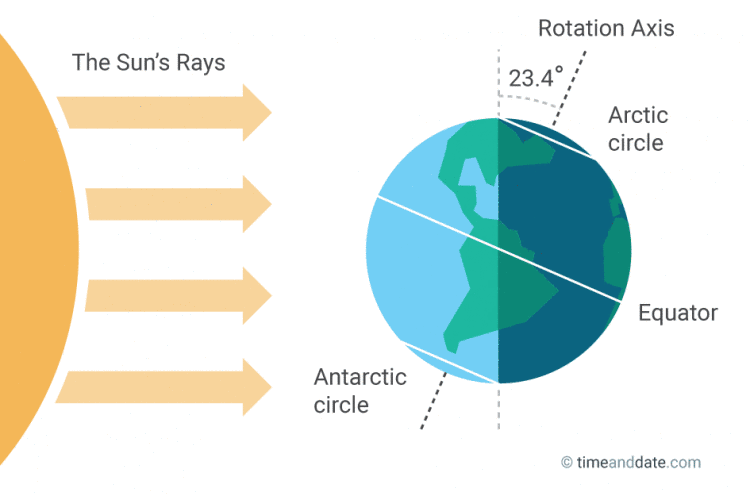

Here Comes the Sun

I was looking up “winter solstice” just to make sure I was thinking about the term right, and I came across this cool diagram. Although we all know (if vaguely) that the tilt of the Earth explains the seasons and the length of the day (though I think these are subtly different effects), for some reason this diagram really drove it home for me in a way that my textbooks as a kid never did.

So, here ya go, taken from this website:

Potpourri

==> Here’s the white paper on “Intercoin.” One of the people associated with the project explained to me that he is a fan of both the Austrian and MMT schools. I think the idea is to decentralize cryptocurrency transactions, so that all of the exchanges taking place within local communities can be confined to their own ledgers. But if someone in local community A wants to trade with someone from community M then they go through the Intercoin market. If I’ve understood the mechanics, it seems like a (voluntary) Bretton Woods-type system, but with Intercoin taking the place of US dollars and local coins acting as francs, marks, lira, etc.

==> RC Sproul has died.

==> My interview on The Money Advantage podcast.

==> Recently Jeff Deist and I spoke in Orlando about the future of liberty. We both discussed issues of culture, federalism, and secession. Here are his remarks and here are mine.

==> Richard Ebeling on Thanksgiving.

Graphs to Accompany Bob’s Commentary During Contra Krugman Episode 117

[EDITed the section about construction employment.]

For this episode, we covered this blog post by Krugman, in which he says that the unemployment rate has now fallen down to pre-crisis levels, and so–duh–the “demand siders” were right, while the “structuralists” were wrong. The reason so many people were unemployed in 2009 and 2010 is that people weren’t spending enough; the claims about a mismatch between worker skills and job openings have been refuted by the data. After all, if the people claiming “structural unemployment” were right, then we should’ve seen spikes in wage growth, among those people who *did* have the desired skills. Yet wage growth has been sluggish, and is only now just recovering, showing that it was always a problem of demand, stupid.

I won’t spoil my responses, but in my commentary I referred to a bunch of charts. So I’ll collect them all here in one place.

The first chart below shows that even according to Krugman’s own narrative, wage growth right now is surprisingly low. Looking back several decades, anytime wage growth (the red line) was as low as it is now, the unemployment rate (blue line) was much higher than it is now. On the other hand, looking back over the decades, anytime the unemployment rate (blue line) was as low as it is now, you’d see wage growth (red line) much higher than you see now. So, my point is that the Keynesian explanation, where the unemployment rate is driven by “slack” in the labor market due to insufficient demand, doesn’t really match the data either. If Krugman’s basic narrative were right, then wage growth should be a lot higher than it actually is right now. And whatever tweak you use to explain the fact away for Krugman’s story, the structuralists could use as well to rescue their story.

This second chart shows total construction employment. Notice that it is still some 700,000 below the pre-crisis peak. This is exactly what the structuralists were saying: employees laid off from construction needed to go elsewhere. If Krugman is saying the labor market is basically back to normal, then the structuralists were right, and he was wrong. [EDITED to add: I agree with Transformer in the comments, that Krugman’s demand-side story isn’t obliterated by a net exodus of workers from construction. However, I’m saying that this evidence lines up better with the structuralist story than with the demand-side story. Back in late 2008, Krugman was mocking John Cochrane for saying the recession was necessary in order to move workers out of construction in Nevada and into other channels. Now in 2017–nine years later–Krugman is looking at what he believes is a fully employed labor market, with 700,000 fewer people in construction, and he’s saying, ‘Wow those structuralists were morons.’ Uh, this is exactly what Cochrane would’ve expected things to look like.]

The third chart below shows the proportion of prime-age males who are employed. To me, this chart indicates that the official unemployment rate is very misleading. Those claiming that globalization, bad schools (look at the chart on page 13 here), growing regulations (including the employer mandate under ObamaCare) were hampering the labor market, could point to this chart and say, “I told you so.” (Note that another factor is the explosion in male incarceration rates that started during the 1980s.)

Finally, look at the mean duration of unemployment spells. Krugman’s basic story shouldn’t predict that the duration would be so much higher during the Great Recession, should it? But it makes much more sense if the structuralists and also guys like Casey Mulligan (who was blaming the extension of unemployment benefits and other incentives) were right.

Recent Comments