Tom Woods and I Talk Japan, Plus a Surprise Announcement

As I said on Facebook, it might be about the Flying Spaghetti Monster we captured. Or should I say, Spaghetti Monster.

The “Best” of Gruber In One Short Video

I’ve already shown the first and third clips on this blog (separately), but the middle one is new to Free Advice.

BTW, Steve Landsburg is cool with Gruber’s handling of the Cadillac tax stuff. I am collecting my thoughts before officially responding, but let’s just say I’m much more receptive to Jim Bovard’s take.

“Lord Keynes” Calls My Raise on Krugman Kontradiction

In my recent post on Krugman’s Kontradiction regarding “contractionary policy is contractionary,” I wrote this:

More generally, Paul Krugman (as well as a gaggle of lesser Keynesian analysts) simultaneously believe the following:

==> The sales tax hike in Japan was obviously a stupid thing to do in a weak economy; of course if you make retail items artificially more expensive, people will buy fewer of them. In any event, there was no need to bring in new revenue this year; any need for budget reform could have been postponed until the recovery had gotten more strength; a few years of additional government debt would be a drop in the bucket.

…

==> A sharp increase in income tax rates on the top earners is a good thing to do, even in the midst of a depressed economy. Anybody who tells you that rich people will work less if you reduce their compensation is a liar or ignorant.

(Note that for brevity’s sake I omitted the middle two examples in the quotation of myself, above. I just wanted to give a flavor of the rhetorical point I was making.)

So “Lord Keynes” (who often goes by “LK” here in the comments) called foul on that last bit. He wrote:

“Nice straw man. Where did Krugman say this? It might be that rich people might work less if the income is taxed at a higher rate, or maybe they won’t. You could hardly predict it with certainty. If they do, then most likely other people will do the work, possibly unemployed people.”

I stuck to my guns, asking if LK would apologize were I to produce a Krugman quote to that effect. LK came back with this:

And before you answer you might like to read this explicit evidence that Krugman doesn’t believe the straw man idea you ascribed to him:

“A note on taxes, benefits, and incentives … . There is no question that incentives matter, that other things equal, someone facing a high marginal tax rate will work less than he or she would otherwise. How much they matter is another issue; in fact, careful empirical study suggests that they matter far less than right-wing mythology would have it.”

Paul Krugman, “Whose Incentives?,” Conscience of a Liberal blog, July 10, 2012.http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/10/whose-incentives/?_r=0

——————-

So, clearly, Krugman:

(1) thinks “incentives matter”,(2) thinks ceteris paribus “someone facing a high marginal tax rate will work less than he or she would otherwise,” but

(3) disputes that the effect on the rich is economically significant and in fact thinks much more attention should be given to lower and middle income earners.

Now a serious question: are you going to admit that Krugman has repudiated the view you ascribe to him? And apologise for using a straw man argument?

Yikes! It looks like LK caught me being sloppy, doesn’t it? LK has produced a quotation from Krugman that sure seems to be the exact opposite of what I said. It doesn’t look good for our karaoke’ing hero, does it?

Well, in this post from 2010 Krugman wrote:

So the way I see it, even quite high marginal tax rates on high earners — even rates in, say, the 70 percent range that prevailed pre-Reagan — are unlikely to put us on the wrong side of the Laffer curve by discouraging effort. High earners won’t work much less; they might even work harder, because it takes more effort to make enough to buy that fourth home.

That doesn’t mean, however, that it’s OK to go back to Eisenhower-era 91 percent top marginal rates. The problem with super-high rates isn’t so much that they reduce incentives to work; it’s that they create huge incentives to avoid or evade.

OK so we’ve got Krugman saying that even 70 percent top income tax rates might yield more work from rich people. Krugman goes so far as to say that even 91 percent top rates aren’t bad because they reduce work incentives.

So at this point, I’ve got Krugman calmly stating the position that I attributed to him. But wait, technically I also said that he makes fun of people who disagree with Krugman on this, and think (say) that 91 percent top tax rates would reduce work incentives. Can I produce a quotation from Krugman where he goes so far as to mock people who think a 91 percent income tax rate might reduce work effort?

Yep, I sure can. In 2012 Krugman wrote:

Consider the question of tax rates on the wealthy. The modern American right, and much of the alleged center, is obsessed with the notion that low tax rates at the top are essential to growth. Remember that Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, charged with producing a plan to curb deficits, nonetheless somehow ended up listing “lower tax rates” as a “guiding principle.”

Yet in the 1950s incomes in the top bracket faced a marginal tax rate of 91, that’s right, 91 percent, while taxes on corporate profits were twice as large, relative to national income, as in recent years. The best estimates suggest that circa 1960 the top 0.01 percent of Americans paid an effective federal tax rate of more than 70 percent, twice what they pay today.

…

Today, of course, the mansions, armies of servants and yachts are back, bigger than ever — and any hint of policies that might crimp plutocrats’ style is met with cries of “socialism.” Indeed, the whole Romney campaign was based on the premise that President Obama’s threat to modestly raise taxes on top incomes, plus his temerity in suggesting that some bankers had behaved badly, were crippling the economy. Surely, then, the far less plutocrat-friendly environment of the 1950s must have been an economic disaster, right?

Actually, some people thought so at the time. Paul Ryan and many other modern conservatives are devotees of Ayn Rand. Well, the collapsing, moocher-infested nation she portrayed in “Atlas Shrugged,” published in 1957, was basically Dwight Eisenhower’s America.

Strange to say, however, the oppressed executives Fortune portrayed in 1955 didn’t go Galt and deprive the nation of their talents. On the contrary, if Fortune is to be believed, they were working harder than ever. And the high-tax, strong-union decades after World War II were in fact marked by spectacular, widely shared economic growth: nothing before or since has matched the doubling of median family income between 1947 and 1973. [Bold added.]

Granted, I’m biased, but I’m going to award victory to myself on this one. A regular Krugman reader would feel perfectly justified in laughing at someone who thought that high income tax rates would discourage high-income earners from generating income on the margin.

Last point: Strictly speaking, there is no contradiction in any of the above, including LK’s quotation. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if LK responds in the comments here, claiming that he obviously won, and demanding that I apologize for my scurrilous remarks.

Specifically, Krugman can simultaneously say that rich people respond to the incentives of the tax code, and that a 91 percent marginal tax rate will make them earn more income, because of the distinction between the income and substitution effects.

Even so, my original point remains: In any given case, Krugman carefully picks his assumptions and emphases to trumpet the policy that progressives like for other reasons.

Jim Carrey Exposes the NWO

This is brilliant. If people in the audience think conspiracy theories about the New World Order (NWO) etc. are ridiculous, then this is a mildly amusing comedy bit. If they think those things are true, then Jim Carrey is a hero who is doing what little he can (without putting himself in mortal peril) to raise the alarm.

Sort of what I’ve done in this post, except, without the comedy.

Paul Krugman: I Have Always Been At War With Tax Hikes

I coined the term “Krugman Kontradiction” to refer to the Nobel laureate’s tendency to lead his readers in one direction on an issue, then do a total about-face when circumstances make that convenient, while whipping up a new set of assumptions and emphases in his economic analysis so as to reconcile the switch. I’ve got a great new illustration of that when it comes to tax hikes and how our Keynesian pundit incorporates them into his model of the world.

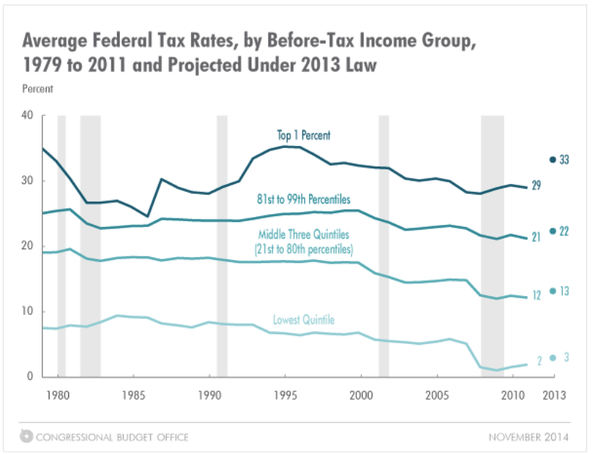

First, on November 13, Krugman had a post called “Why the One Percent Hates Obama.” He had the following commentary and graph:

A peculiar aspect of the Obama years has been the disconnect between the rage of Obama’s enemies and the yawns of his sort-of allies…

The latest case in point: taxes on the one percent. I keep hearing that Obama has done nothing to make the one percent pay more; the Congressional Budget Office does not agree:

According to CBO, the effective tax rate on the one percent — reflecting the end of the Bush tax cuts at the top end, plus additional taxes associated with Obamacare — is now back to pre-Reagan levels. You could argue that we should have raised taxes at the top much more, to lean against the widening of market inequality, and I would agree. But it’s still a much bigger change than I think anyone on the left seems to realize.

Notice that in the above graph, everybody saw an income tax hike, not just the “one percent.” Yet Krugman didn’t even bother to mention that; his single-minded focus was on the fact that Obama hadn’t gotten enough fist-bumps from progressives on taking more money away from rich people.

Four days later, on November 17, when the bad news of Japan’s GDP contraction came out, Krugman wrote:

Terrible numbers from Japan. Probably the drop was overstated — I don’t have any special knowledge here, but other indicators didn’t look quite this bad. But still, no question that the ill-considered sales tax hike of the spring is still doing major damage.

Fairly clear now that Abe won’t go through with round two, which is good news.

So contractionary policy is contractionary. I could have told you that, and in fact have told you that again and again. But some people still don’t get the message.

So now all of a sudden Krugman can’t believe these idiots who would raise taxes in the midst of a weak economy. Why haven’t they been listening to guys like him?!

More generally, Paul Krugman (as well as a gaggle of lesser Keynesian analysts) simultaneously believe the following:

==> The sales tax hike in Japan was obviously a stupid thing to do in a weak economy; of course if you make retail items artificially more expensive, people will buy fewer of them. In any event, there was no need to bring in new revenue this year; any need for budget reform could have been postponed until the recovery had gotten more strength; a few years of additional government debt would be a drop in the bucket.

==> Imposing a stiff carbon tax immediately is an imperative for all major governments; of course if you make carbon dioxide emissions artificially more expensive, people will emit fewer tons of CO2. The possible harm to the world economy is irrelevant compared to the need to reduce emissions this year, not (say) starting three years from now.

==> A sharp increase in the minimum wage is a great thing to do immediately. Anybody who warns that employers will obviously reduce their hiring of workers when they suddenly become much more expensive, is a liar or ignorant.

==> A sharp increase in income tax rates on the top earners is a good thing to do, even in the midst of a depressed economy. Anybody who tells you that rich people will work less if you reduce their compensation is a liar or ignorant.

Now on all of the above issues, is Krugman literally contradicting himself? Not really; he can always come up with some case-specific argument to justify the conclusion. But it’s interesting that his objective economic modeling just so happens to spit out results that progressives like for other reasons.

Fox News Compilation of Democrats Praising Gruber

Yes it’s from Fox but the footage speaks for itself…

“NGDP” Is An Artificial Construct Invented By Economists

Don’t let Scott Sumner tell you otherwise. The meat from my latest Mises CA post:

Regardless of the usefulness of (nominal) GDP as an economic statistic, Scott Sumner (and perhaps some of his fellow Market Monetarists) are incorrect when they lead their readers to believe that this is a “raw” empirical fact, which requires no conceptual judgment calls by the economist (the way that real GDP requires an adjustment for the “price level”). In the real world, you could give two teams of economists the same data on nominal expenditures in an economy, and they would come up with different answers for “nominal GDP” if they weren’t allowed to communicate with each other. That’s because the dividing line between “final” and “intermediate” goods and services is somewhat arbitrary.

For example, in a textbook treatment they would say that if a baker buys flour that is completely turned into bread and sold to his customers, then the expenditure on the flour doesn’t count in GDP. But if that same baker buys a new oven, then the expenditure counts in GDP as part of investment. But what about the fact that a fraction of the oven depreciates during the year, and effectively “turns into” the loaves of bread, in terms of accounting? This is the distinction between fixed and working capital, but the proper way to apply it in the real world is somewhat arbitrary. I am quite sure that the average fan of Market Monetarism has not thought through the subtleties involved.

Note that this complication affects the equation of exchange, too. People routinely thinkMV=PQ involves multiplying the number of dollars by the amount of times a dollar bill turns over, on average. But if you want the “Q” on the right hand side to refer to GDP–which economists usually mean–then you have to talk about the velocity regarding a final good or service. In other words, “How many times does the average dollar bill change hands, in a transaction that involves a final good or service?” That makes “V” much weirder than it already is, as a variable to be used in a discipline that ostensibly embraces methodological individualism rather than mindless aggregates.

God, Time, and Action

One of the great things about Tom Woods’ recent exposition of one of Thomas Aquinas’ proofs of God, is when Tom makes a crucial distinction: Aquinas was not making a chronological argument, saying that at some point in the past, a First Mover must have set everything in motion in order to explain today’s state of the universe. On the contrary, Tom explained, Aquinas showed that God needed to exist in order to support the universe at every moment.

This links up nicely, I think, with my view on miracles and physical law. I don’t think it makes sense to say, “Usually the universe unfolds according to the mechanical laws of physics, but every once in a while God intervenes to accomplish His will.” That is nonsensical both on scientific and theological grounds.

As an added bonus, this notion of God being outside of time itself–rather than creating everything “in the beginning” and then moving through time with us–also resolves a standard paradox that Mises brought up. According to Mises, the notion of an acting omnipotent being makes no sense, because action requires unease and an omnipotent being would have eliminated all uneasiness in one fell swoop.

Right, I agree. But I think a better framework for thinking about this is to view God deciding on the entire history of the physical universe first, then willing it all into being. From His perspective, the events in Genesis are happening at the same moment as the events in Revelation. It’s not that God first creates the world, then watches unfolding events to make sure they go the way He planned. No, He directly wills every moment of existence into reality, all in one fell swoop (from His perspective).

This also resolves the standard skeptic taunt of, “If God is so smart, why did he have to reboot his creation with the flood?” I agree that’s a deep issue, but it’s not that God was surprised by what happened. He knew all along that He would flood the Earth. To suggest otherwise is like saying, “George Lucas had to rewrite the script once Anakin turned to the dark side.”

Last thing, for those of you who don’t like me veering off into my own conjectures rather than staying tied to Scripture: Notice that my perspective above makes perfect sense for a being who introduces Himself as “I AM.” When I was younger, that phrase struck me as odd. But that’s because I was (like Mises) viewing God as a really powerful being operating inside the constraints of time. Once you fully appreciate the significance of a being identified as “I AM,” Mises’ critique wilts away.

Recent Comments