Paul Krugman: I Have Always Been At War With Tax Hikes

I coined the term “Krugman Kontradiction” to refer to the Nobel laureate’s tendency to lead his readers in one direction on an issue, then do a total about-face when circumstances make that convenient, while whipping up a new set of assumptions and emphases in his economic analysis so as to reconcile the switch. I’ve got a great new illustration of that when it comes to tax hikes and how our Keynesian pundit incorporates them into his model of the world.

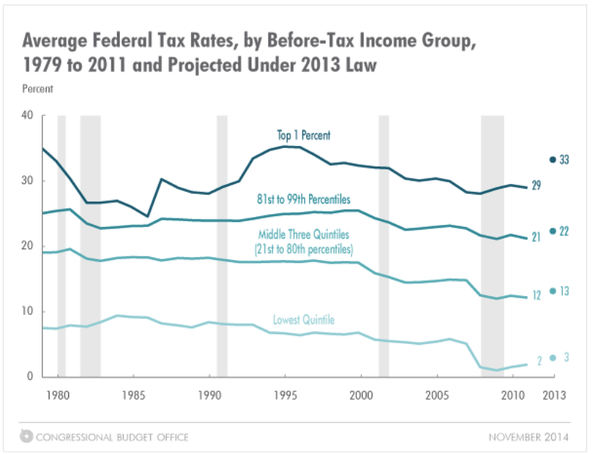

First, on November 13, Krugman had a post called “Why the One Percent Hates Obama.” He had the following commentary and graph:

A peculiar aspect of the Obama years has been the disconnect between the rage of Obama’s enemies and the yawns of his sort-of allies…

The latest case in point: taxes on the one percent. I keep hearing that Obama has done nothing to make the one percent pay more; the Congressional Budget Office does not agree:

According to CBO, the effective tax rate on the one percent — reflecting the end of the Bush tax cuts at the top end, plus additional taxes associated with Obamacare — is now back to pre-Reagan levels. You could argue that we should have raised taxes at the top much more, to lean against the widening of market inequality, and I would agree. But it’s still a much bigger change than I think anyone on the left seems to realize.

Notice that in the above graph, everybody saw an income tax hike, not just the “one percent.” Yet Krugman didn’t even bother to mention that; his single-minded focus was on the fact that Obama hadn’t gotten enough fist-bumps from progressives on taking more money away from rich people.

Four days later, on November 17, when the bad news of Japan’s GDP contraction came out, Krugman wrote:

Terrible numbers from Japan. Probably the drop was overstated — I don’t have any special knowledge here, but other indicators didn’t look quite this bad. But still, no question that the ill-considered sales tax hike of the spring is still doing major damage.

Fairly clear now that Abe won’t go through with round two, which is good news.

So contractionary policy is contractionary. I could have told you that, and in fact have told you that again and again. But some people still don’t get the message.

So now all of a sudden Krugman can’t believe these idiots who would raise taxes in the midst of a weak economy. Why haven’t they been listening to guys like him?!

More generally, Paul Krugman (as well as a gaggle of lesser Keynesian analysts) simultaneously believe the following:

==> The sales tax hike in Japan was obviously a stupid thing to do in a weak economy; of course if you make retail items artificially more expensive, people will buy fewer of them. In any event, there was no need to bring in new revenue this year; any need for budget reform could have been postponed until the recovery had gotten more strength; a few years of additional government debt would be a drop in the bucket.

==> Imposing a stiff carbon tax immediately is an imperative for all major governments; of course if you make carbon dioxide emissions artificially more expensive, people will emit fewer tons of CO2. The possible harm to the world economy is irrelevant compared to the need to reduce emissions this year, not (say) starting three years from now.

==> A sharp increase in the minimum wage is a great thing to do immediately. Anybody who warns that employers will obviously reduce their hiring of workers when they suddenly become much more expensive, is a liar or ignorant.

==> A sharp increase in income tax rates on the top earners is a good thing to do, even in the midst of a depressed economy. Anybody who tells you that rich people will work less if you reduce their compensation is a liar or ignorant.

Now on all of the above issues, is Krugman literally contradicting himself? Not really; he can always come up with some case-specific argument to justify the conclusion. But it’s interesting that his objective economic modeling just so happens to spit out results that progressives like for other reasons.

“Lack of transparency is a huge economic advantage and, basically, call it the stupidity of the typical Krugman fanboy or whatever. But basically that was really critical to getting that past the editors.”

Except that’s the difference between Gruber and Krugman; Krugman would never be so stupid to say that out loud.

Well he did call you and Don Boudreaux “idiots.”

“I coined the term “Krugman Kontradiction” to refer to the Nobel laureate’s tendency to lead his readers in one direction on an issue, then do a total about-face when circumstances make that convenient, while whipping up a new set of assumptions and emphases in his economic analysis so as to reconcile the switch.”

I think the definition is slightly different or at least more general than that, no? I mean, what Krugman also does often is write something that strongly suggests X but does not literally say X while leaving himself enough room to deny that X is what he meant, in case he ever needs to.

He wants this plausible deniability because he wants to have it both ways:

– he wants his (e.g. leftist, popular) audience to think that he is saying X because doing so makes rhetorical sense (e.g. it caters to the beliefs, likes/dislikes, biases of his audience; it helps him in a debate)

– he doesn’t want to have to *defend* X because X more or less contradicts other things he’s said or thinks or wants to be seen as thinking (e.g.by colleagues) or what he thinks he could plausibly defend (against sophisticated critics).

So when Krugman strongly suggests but does not actually say X it is a Kontradiction: A Kontradiction occurs when:

– Krugman will write something that says or strongly suggests X

– Getting (some members of) his audience to believe that he meant X serves rhetorical purposes

– Getting (the same or other members of) his audience to believe that he said, meant, believes Y serves (the same or different) rhetorical purposes.

– X and Y appear to be in contradiction with each other (and so getting the *same* members of his audience to *consciously and explicitly* believe both X and Y would be problematic)

– Krugman has worded the statements that say or suggest X and/or the statements that say or suggest Y in such a way that he can plausibly deny, if he needs to when confronted by critics, that X and/or Y are what he said or meant.

These conditions covers both the type of Kontradiction that you mention and the type of Kontradiction i described above, i.e.:

#1 The instances wherein he appears to be embracing a general principle in one case but not in another. In these instances he can always argue that there are relevant differences between the two situations that make the general principle apply (or be a primary causal force) in one but not in the other.

#2 the instances wherein he writes something in a way that strongly suggests that he means X while leaving himself enough room to deny that X that is what he meant.

One problem with #1 qualifying as a Kontradiction is that #1 can actually be and often is an epistemically rational strategy, and need not at all be a sign of malice or intellectual dishonesty. So perhaps the definition of a Kontradiction should include an element of malice or intellectual dishonesty.

One problem with that solution, however, is that that makes the definition much more difficult to apply objectively / mechanically. And if that is the case, then one major benefit of analyzing exactly how Krugman does exactly what he does and describing it as analytically as possible, is gone.

I think the definition is slightly different or at least more general than that, no? I mean, what Krugman also does often is write something that strongly suggests X but does not literally say X while leaving himself enough room to deny that X is what he meant, in case he ever needs to.

He wants this plausible deniability because he wants to have it both ways:

Yes I agree Krugman’s shenanigans go beyond my narrow definition.

Krug’s body language says it out loud to me.

“A sharp increase in income tax rates on the top earners is a good thing to do, even in the midst of a depressed economy. “

Except America is not in recession today. It has not been in recession since 2009. It has had positive real output growth since middle 2009, and even if employment growth has been weak, raising taxes on the top income earners will not necessarily depress economic activity since the rich and ultra rich have a lower marginal propensity to consume.

So why just ignore the well known empirical evidence of the clear difference in marginal propensities to consume between different income earners and what Keynesian theory actually says about this here?

raising taxes on the top income earners will not necessarily depress economic activity since the rich and ultra rich have a lower marginal propensity to consume.

So why just ignore the well known empirical evidence of the clear difference in marginal propensities to consume between different income earners and what Keynesian theory actually says about this here?

Right, so if Obama had raised taxes *only* on the one-percent, your argument would make sense.

-Same with Japan.

Try to read the post next time, LK. Did you notice that taxes for _all_ income groups have risen?

LK:

“It has had positive real output growth since middle 2009, and even if employment growth has been weak, raising taxes on the top income earners will not necessarily depress economic activity since the rich and ultra rich have a lower marginal propensity to consume.”

It is comments like this that show the vulgar Keynesian doctrine that consmption grows economies is in fact alive and well among self-professed Keynesians.

LK, you have been corrected on that false claim a million times. Consumption is not the cause of growth. Consumption shrinks the economic pie. It is only saving and investment that grows economies.

Yes, at the micro level producers depend on consumers for revenues which are necessary for subsequent saving and investment. However it is a fallacy of composition to assert that this is true at the level of the economy as a whole. At that level of the whole, the dependency is the other way around. At this level, which is the level under discussion, consumption as such depends on production as such.

You can easily grasp this by considering what would happen if consumer spending spending rises…and rises and rises…without there being enough of that evil saving and investment you seem to have no clue to be the cause of growing economies. If consumer spending keeps rising, it is capable of resulting in enough real consumption activity that real productive activity cannot replace what is consumed. The economy would shrink.

The only activity that adds to the economic pie is saving and investment activity. You cannot consume what has not yet first been produced, and production requires non-consumption spending. Every material, every labor hour, every machine, every means of production requires expenditures that are by definition not consumption expenditures.

Consumption shrinks the pie. Production adds to the pie. Period. End of story.

You are advocating for a poisonous, destructive activity.

You are an ignoramus, Major.Freedom.

Neither Keynes nor Keynesians deny that economies need investment for growth and creation of real output. Most of the General Theory is devoted to investment, not consumption.

Saying that demand for final consumer output is a major inducement to invest does not deny the role of investment.

Keynesian economics was just put to the test throughout the developed world in case you didn’t notice. The evidence speaks for itself, it was right.

This is facepalm worthy. If you have too much demand and not enough supply we don’t run out of things to consume, we get inflation. Too many consumers chasing too few goods. Likewise when you have too much production for the demand you get deflation.

It isn’t this bizarre question as to whether we want more consumption or more production, as either one alone is pointless. It is a question of what drives our economy to grow. Apparently you think that when people produce more everyone suddenly decides they want whatever was produced, Steve Jobs style. I would say that most often there is a demand for a product and therefore someone invests in a factory or whatever to make it, but regardless it is the interplay of the two that matters.

Currently, as shown by inflation statistics, we have too little aggregate demand.

MF, Consumption is how we grow an economy In fact, if we all just made things nobody wanted we would have no consumption and therefore the biggest economy ever. It can’t possibly go wrong.

Seriously though I’m baffled at the production vs. consumption idea you push there as if consumption were a bad thing.

LK:

“So why just ignore the well known empirical evidence of the clear difference in marginal propensities to consume between different income earners and what Keynesian theory actually says about this here?”

Why do you ignore the implication of that nonsense theory that it would benefit everyone if poor people held rich people at gunpoint at stole their money to blow it all on beer, drugs and junk food?

“Except America is not in recession today…..”

Nonsense. The gov’t official GDP deflator is a fantasy.

“Anybody who tells you that rich people will work less if you reduce their compensation is a liar or ignorant.”

Nice straw man. Where did Krugman say this? It might be that rich people might work less if the income is taxed at a higher rate, or maybe they won’t. You could hardly predict it with certainty. If they do, then most likely other people will do the work, possibly unemployed people.

Wait LK: If I show you where Krugman said words very much to this effect, are you going to apologize for calling it a strawman? Or are you going to bluster through and act like I’m still a jerk? (Incentives matter. I’m not going to bother looking it up if there’s no hope of reward.)

If you can provide citations of Krugman saying that “Anybody who tells you that rich people will work less if you reduce their compensation is a liar or ignorant” or convincing words of his to that effect, then I am perfectly happy to withdraw my comment and apologise to you for it.

And before you answer you might like to read this explicit evidence that Krugman doesn’t believe the straw man idea you ascribed to him:

“A note on taxes, benefits, and incentives … . There is no question that incentives matter, that other things equal, someone facing a high marginal tax rate will work less than he or she would otherwise. How much they matter is another issue; in fact, careful empirical study suggests that they matter far less than right-wing mythology would have it.”

Paul Krugman, “Whose Incentives?,” Conscience of a Liberal blog, July 10, 2012. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/10/whose-incentives/?_r=0

——————-

So, clearly, Krugman:

(1) thinks “incentives matter”,

(2) thinks ceteris paribus “someone facing a high marginal tax rate will work less than he or she would otherwise,” but

(3) disputes that the effect on the rich is economically significant and in fact thinks much more attention should be given to lower and middle income earners.

Now a serious question: are you going to admit that Krugman has repudiated the view you ascribe to him? And apologise for using a straw man argument?

That was Krugman two years ago. Who knows how his thoughts have changed post-Pikkety?

Krugman wrote a blog post “Of Janitors and Job Creators” where he basically said that, although not those exact words.

I’d quote, except that NYT is paywalling Krugman these days, so only the true believers can still read it, which makes sense because for a while now Krugman has only been writing for the true believers.

Great article. Never enough Krugman Kontradictions. Is this a preview of a possible Krugman Kontradiction podcast??

“Notice that in the above graph, everybody saw an income tax hike, not just the “one percent.” ”

Yes, but would you concede that it rose only by 1 percent on ave for the other percentiles? and that is small relative to the top earners?

Sure GabbyD. How does 1% of income translate into expenditures on items hit by a sales tax hike? Are you saying taking away 1% of a poor person’s income is nothing compared to making groceries 3% more expensive?

Bob, if Krugman were asked about the fact that taxes on the poor we’re increased by 1%, don’t you think he would say that that’s bad policy?

Bob, if Krugman were asked about the fact that taxes on the poor we’re increased by 1%, don’t you think he would say that that’s bad policy?

?!?!!? Krugman posts a graph about what Obama did with taxes, says it’s too bad Obama doesn’t get more credit for his accomplishment, and you want to think he implicitly condemned a lot of the graph?

I don’t think Krugman was even thinking about the rest of the graph. He was just trying to address the complaint “that Obama has done nothing to make the one percent pay more”. But I’m almost certain that if he were asked about the rest of the graph, he would say that it’s bad policy. In fact I think Krugman would be in favor of a tax cut on the poor.

“In fact I think Krugman would be in favor of a tax cut on the poor.”

Unintended consequences: The rich choose to produce less in order to be taxed less, and the resulting higher marginal utility of that which is produced means higher prices, thereby making the poor poorer.

guest, I’m not trying to defend the merits of Krugman’s beliefs. I’m just trying to explain what he believes.

“Are you saying taking away 1% of a poor person’s income is nothing compared to making groceries 3% more expensive?”

I’m saying its LESS, certainly not nothing. also, groceries are a larger share for the poor, making an increase in a consumption tax more felt by the poor. would you agree with that?

BOB wrote: “Are you saying taking away 1% of a poor person’s income is nothing compared to making groceries 3% more expensive?”

GABBY D answered: “I’m saying its LESS, certainly not nothing.”

So you think in the United States (or Japan), the average household spends more than a third of its income on groceries?

http://www.pkarchive.org/japan/jpeffect.html

… also …

They pretty much did exactly what he asked them to do in 1998, so banging on about the sales tax rise is the only thing he has.

As Sumner has pointed out, the Bank of Japan has a de facto CPI inflation target of 0% and a GDP deflator deflation target of -1%.

http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2013/01/22/bank-of-japan-sets-2-percent-inflation-target/1854371/

And that was two years ago.

Let’s see in five years if that’s credible.

Good point Tel.

Note the first comment on the Krugman post mentioning taxes is:

Whatever neoliberal remains of Krugman will cease to exist by 2020.

An excellent illustration of the Conspiracy Theory of Economics.

The economy’s bad BECAUSE RICH PEOPLE GUYS! Because RICH PEOPLE!

Also, wasn’t the recession of 1937 preceded by a massive tax hike and sizable labor supply shock?

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=DTZ (change the intervals on the last two series from yearly to monthly)

http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/docs/historical/eccles/073_08_0001.pdf

Ah, but it is then the 1932 and 1937 tax hikes are called “austerity”. Because Good Progressives, who would never support a tax cut, are the Rational People who Understand the Lessons of 1937.

OK. Point: Murphy. For Krugman “tax the rich” and “stay out of recession” are competing values. He wants to do each, but will only claim to have supported one to the extent that it didn’t affect the other too much.

“The possible harm to the world economy is irrelevant compared to the need to reduce emissions this year, not (say) starting three years from now.” The same argument applies to stopping smoking. It is always better to put it off until tomorrow.

“Notice that in the above graph, everybody saw an income tax hike, not just the “one percent””. Yeah, but his point is “the effective tax rate on the one percent is now back to pre-Reagan levels.” The CBO report says “The estimated rates under 2013 law would still be well below the average rates from 1979 through 2011 for the bottom four income quintiles, slightly below the average rate over that period for households in the 81st through 99th percentiles, and well above the average rate over that period for households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution.” The tax rate for everyone else is lower, but for the top 1% it is higher, which does indicate a different treatment for the 1%.

Harold wrote:

The same argument applies to stopping smoking. It is always better to put it off until tomorrow.

Is it that you guys are slow on the uptake, or are you willfully ignoring my point in all of this?

Look, on any given issue, Krugman is free to pick whatever judgment-call he wants, in terms of procrastination etc. But my point was, when it comes to climate change, Krugman strongly argues that the long-term problem needs to be addressed *right now* if we’re going to save the planet (his term, not mine).

Yet when it comes to Japan’s massive government debt, Krugman strongly argues that the long-term problem doesn’t need to be addressed right now.

And in both cases, the tradeoffs are similar.

Oh – I get it – you are pointing out a contradiction! Why didn’t you say? Sorry – I was woefully slow on the uptake. I will just go and have a smoke.