American People Don’t Know Basic Economics Because Economists Have Misled Them

[UPDATE: As Keshav and David pointed out in the comments, I made a bonehead mistake in the original draft of this post, which ironically strengthens my underlying point rather than hurting it. I’ve corrected the mistake below, and in a follow-up post I’ll deal with this issue more directly.]

Steve Landsburg recently wrote a post entitled, “In Defense of Gruber.” Now Steve likes to write provocative things, so I was curious to see how he could possibly approach this seemingly impossible task. I think Steve failed–badly–but it’s because he is not really being fair with the average non-economist. Precisely because you’ve got ostensible giants in the field misleading Americans about the state of the economics literature, it’s not the average person’s fault for believing the deception that Gruber helped foster.

Below, I’ve excerpted the gist of Steve’s post. For the context, remember that Gruber (among other controversial things) told an audience that taxing insurance companies for high-premium employer-provided health plans (tax on “Cadillac plans”) was the same thing as eliminating the favorable tax treatment of those plans, which they currently enjoy because employer contributions to premiums are not considered taxable compensation to the employee. Gruber thought it was hilarious that the American people were too ignorant to see that these were the same policies, and his audience laughed along with him. Now Steve favors eliminating this special tax treatment that encourages employers to pay in the form of insurance premiums rather than salary, and so Steve agrees with Gruber that it’s a good part of ObamaCare to crack down on these Cadillac plans. So here’s how Steve justifies Gruber’s participation in this scheme to obfuscate what this “Cadillac tax” would actually do to average Americans:

7) So — here we have two different policies with exactly the same effects — tax the consumer or tax the insurance company. Gruber et al. believed that the voters would oppose one and support the other. It does not seem to me, under those circumstances, that it’s especially dishonest to choose the package that you think will sell. If voters have opinions that are completely incoherent to begin with, then neither Gruber nor anyone else can be accused of confusing them. They were, after all, maximally confused in the first place.

8) I do think that those of us who are paid to teach economics have something of a moral obligation to, you know, teach economics. So it would have been better if Gruber, like so many of the rest of us, had made some effort to explain to the public that there is no difference between paying a tax and having a taxed passed on to you. On the other hand, the public is confused about enough different things that we can’t all be explaining all of those things all the time.

9) I want to say this again. If the voters favor a law that says all drivers must be licensed, but oppose a law that says nobody without a license is allowed to drive, then I don’t think it’s immoral to propose the first law instead of the second. That’s basically all Gruber did. I would prefer that he had tried to point out the inconsistency, but Gruber is under no obligation to live by my preferences.

10) Bottom line: The Cadillac tax is a good thing and Gruber found a way to make a good thing politically palatable, without telling any out-and-out lies (as far as I know, he never tried to claim that the tax would not be passed down). I see no sin in that.

No, this is a terrible analogy, even if we agreed with Steve’s moral stance (which I don’t). It’s not “incoherent” for the average American to (a) not want a tax to be levied on him and (b) be OK with a tax levied on the insurance company. You can disagree with the selfish, unprincipled morality of such views, but there’s nothing contradictory about them.

In order to believe these views to be contradictory, you have to subscribe to a particular economic theory of cause-and-effect. Namely, you have to think a tax levied on the insurance company will be fully “passed on” to the consumer market prices adjust in either case such that the consumer is equally affected by a tax levied on him versus the seller.

Rather than focusing on the narrow issue of tax incidence in the health insurance market, consider the following “facts” about the world that a reader of Nobel laureate Paul Krugman would understandably believe. And note carefully, I said “understandably believe,” which is not the same thing as “correctly interpret as the finely nuanced position that Krugman was actually stating.”

==> Imposing energy efficiency mandates that force businesses to buy new equipment and install insulation on their buildings would actually stimulate the economy, as well as help the environment. [Sorry I can’t find link right now to Krugman saying this, but trust me he has–citing liquidity trap and obsolescence leading to forced investment.] Don’t let the right-wing think tanks tell you such mandates will stifle growth or job creation; they are lying.

==> More than doubling the minimum wage to $15 would have hardly any effect on employment in the fast food industry. The right-wingers warning of job losses are ignoring all of the best research.

==> There is “zero evidence” that marginal income tax rates have an effect on economic growth. In fact, if the government raised the top income tax rate to 70 percent or possibly even 91 percent, there’s no reason to expect it to have a big effect on how much rich people work, or the growth of the overall economy. Don’t believe those lying conservatives when they tell you we need low taxes on rich people in order to spur job creation. (In fact, to argue that rich people somehow contribute on net to the economy contradicts free-market economics; that’s how idiotic these right-wingers are.)

==> Strong measures to limit carbon dioxide emissions would be very cheap, possibly even free. Don’t listen to the right-wingers who keep warning about a carbon tax somehow hurting the economy. These people haven’t studied the literature, or they’re lying.

==> Advocates of fiscal austerity keep warning that the invisible bond vigilantes might suddenly attack the currency, and that’s why we need to get government debt under control. What these morons don’t realize is that a speculative attack on the USD or Japanese yen would actually help our countries. Man these right-wingers are cruel and stupid.

==> People keep lambasting government waste, saying we should only invest in smart, cost-effective public projects. No, that’s wrong. Compared to the status quo, it would be preferable if we erroneously believed aliens were about to invade, so we could all build up our militaries with–what turned out to be–useless equipment. That would stimulate the world economy and end this depression now. I don’t need to tell you–but I will–that the people arguing that wasteful government spending is wasteful, don’t understand that economics has advanced since 1936.

Now suppose you are a regular reader of Paul Krugman. He won the Nobel Prize in economics, taught at Princeton for a long time, and has sold a bunch of books, both popular books and texts that other professors adopt. So Joe Sixpack would understandably think that this guy Krugman is no slouch. If Krugman has led Joe Sixpack to believe all of the above, over the years, and then Jon Gruber comes along with his fancy computer models telling everybody how much premiums will go down with ObamaCare…then Steve Landsburg is going to come along and scold Joe Sixpack for holding “incoherent” values if he simultaneously doesn’t want the government to levy a new tax on him, but instead to put it on the rich insurance companies?

Couldn’t Krugman come up with some kind of liquidity trap argument, or cite the famous Kenneth Arrow paper that “proved” the free market doesn’t work when it comes to health care, or talk about cartels and market power among the health insurers…to argue that these two taxes aren’t equivalent as a matter of logic?

Sorry Steve, but if you want to write “In Defense of Gruber,” I think your only chance is to go like this:

(1) Gruber is the economist equivalent of Count Dooku–trained as a Jedi to protect the weak, yet instead serves the Sith lord.

(2) The one good thing about Gruber is that he was shockingly frank about how he and his clique had deceived everybody, and the contempt with which they hold average Americans.

(3) Therefore, Americans will now take people like me more seriously when I warn them about these nasty characters.

(4) I’ve even got a catchy title, Steve! “More Lying Is Safer Lying”

Yes Scott Sumner Is “the NGDP Guy”

I explain why he has been pigeonholed. For example, he has said the Fed is more powerful than God because it controls NGDP.

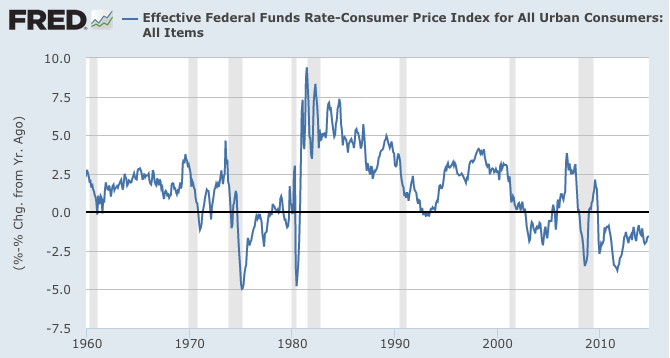

More substantively, I produce the following chart:

So yes, Scott is right that some economists foolishly thought monetary policy was tight in the Weimar Republic because nominal interest rates were high. But if we adjust for Consumer Price inflation, we can see that the “real” fed funds rate lately has been quite low. The only other times (since 1960) it’s been like this, have been in the late 1970s–when Scott agrees Fed policy was too loose–and during the peak of the housing bubble years. Why, it’s almost as if the Austrian narrative makes perfect sense…

Potpourri

==> Dan Sanchez weighs in on Bitcoin and the regression theorem.

==> CATO’s monetary conference.

==> Some Protestant pastors want to separate marriage and State.

==> I’m not going to bother writing it up, but you can see in the comments here how I try to resolve Scott Sumner’s running feud with Paul Krugman. I am a peacemaker.

==> At this point, I have broken beyond the narrow Austro-libertarian world. I’m…kind of a big deal.

==> I agree heartily with Jeff Tucker’s review of the new “Hunger Games,” though be careful there are mild spoilers. Don’t read if you plan on watching the movie soon (and haven’t read the books).

==> The podcast I did at the Acton Institute following my talk on sound money.

Landsburg Agrees That Paul Krugman (Often) Is an Anti-Economist

Since I’m still getting ready to hammer him for his defense of Gruber post, I want to make sure to heap kudos on Steve’s most recent post on Krugman, regarding Krugman’s post defending Obama’s immigration announcement. Some key excerpts:

Dammit, I hate this stuff. Krugman says (and I agree with him) that it’s cruel to deport people. He ignores the fact that it’s also cruel to keep other people out. Krugman says (and I agree with him) that letting more people in would put pressure on the welfare system. He ignores the fact that allowing people to stay also puts pressure on the welfare system. Why should we prioritize kindness to those who are already here over kindness to those who are clamoring to get here?

There might be a really good answer to that question, but you’d never know it from reading Krugman. In fact, the takeaway from Krugman’s column is that the cruelty of deportations is unacceptable only because Krugman says so, and the cruelty of closed borders is a necessary evil only because Krugman says that too. So the next time you want to know whether some other policy is unacceptably cruel or not, the only way to find out is to ask Paul Krugman.

…

According to Krugman, if you support the cruelty of deportations, you’re an evil person, but if you support the cruelty of closed borders, you’re a pragmatic adult. Why? Because Paul Krugman said so. Might there be a subject — like, oh, say, economics — that can help us think more clearly and systematically about such issues? If so, you’d never learn about it by reading Krugman. He wouldn’t want to risk teaching his readers to think.

BTW, I really have not studied the immigration issue enough to comment on Obama’s announcement per se. The only thing I would reiterate is that I think it’s a bad idea for ultra-libertarians to refer to their position as “open borders,” since it’s not really what they believe and it is a red flag to those supporting a stronger State-enforced border.

“The Historical Case for the Resurrection of Christ”

One of my (online) students sent me this essay from his brother, Ashby Camp. Besides the content of the essay, I appreciated its very nature, which Camp describes in the opening:

When I say “the historical case for Jesus’ resurrection,” I mean I am going to approach the question without relying on the inspiration or inerrancy of the Bible. Though I certainly believe in the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture, I think it is important to see that one need not start from that position to conclude that Jesus was resurrected. Even if one treats the New Testament documents as one would treat any other ancient documents, there are very good reasons for believing that Jesus rose from the grave.

I say this because I actually heard a Christian (I think it was on the radio) say something like, “Sometimes people ask me how can I know the Bible is true? Well it says in Psalm such-and-such…” I almost drove off the road.

Camp advances several independent arguments in his essay, but one of the central points is that either the early Christians truly believed Jesus had come back from the dead, or they were deliberately inventing falsehoods to try to give credibility to their (dead) Teacher’s message. But the problem with that second option (Camp shows) is that there are several obvious stumbling blocks in the gospel accounts–for example, the original eyewitness testimony being from women, who were not considered credible witnesses in that culture. If the story were a complete fabrication after the fact, it is odd that Jesus’ disciples would have included awkward details such as this.

I also enjoyed Camp’s dwelling on the fact that even those who believed Jesus to be the Messiah weren’t expecting Him to be crucified (and then resurrected); this was inconceivable to them, since the promised Messiah was supposed to deliver them from their oppressors.

The fact the disciples were not expecting Jesus to be resurrected within history, despite what he had told them, is confirmed by their reaction to his death. None of them said, “Don’t worry; he’ll be back in a few days.” Rather, their hopes were crushed; they went into hiding. You can feel the despair in the disciple Cleopas’s statement in Lk. 24:21. He said to the unrecognized Jesus on the road to Emmaus that they “had hoped

that [Jesus] was the one to redeem Israel,” the implication being “but they crucified him so he could not have been.”Even when the women reported to the apostles and the others that the tomb was empty and that angels had announced Jesus’ resurrection, they did not believe them (Lk. 24:1-11). Thomas had everybody telling him that the Lord had risen, and he said he would not believe it unless he could see that the allegedly resurrected Jesus had distinguishing marks of crucifixion and could feel those marks and the solidity of Jesus’ body (Jn. 20:24-25).

Anyway, let me know what you guys think in the comments.

Potpourri

==> My wise-guy post over New York City’s goal to reduce CO2 emissions.

==> My post on conservatives and carbon taxes. (More academic.)

==> Greek philosophers playing Texas Hold ‘Em. Super geeky.

==> Elon Musk says we’re close to killer robots.

==> Richard Ebeling talks about the Berlin Wall.

==> Good news! New peer-reviewed paper suggests climate models may have been overstating the equilibrium climate sensitivity because of poor modeling of soil feedbacks. I didn’t delve into the paper but others have told me if the results are correct, the effect is very large compared to the ostensible human contribution. All of the scientists should be either rejecting this study or breathing a huge sigh of relief that we don’t need massive government interventions in the energy sector after all.

Steve Landsburg Reminds Us How Little Math We Know

This is a really neat post, if you want to see Steve explain the accomplishments of the recently deceased mathematician Alexander Grothendieck. It would be pointless for me to try to convey the substance of the post; you should just read it if you are interested.

However, let me once again observe that Steve is the most religious atheist I have ever known. Here’s how he opens his post:

I never met Alexander Grothendieck. I was never in the same room with him. I never even saw him from a distance. But whenever I think about math — which is to say, pretty much every day — I feel him hovering over my shoulder. I’ve strived to read the mind of Grothendieck as others strive to read the mind of God.

Those who did know him tend to describe him as a man of indescribable charisma, with a Christ-like ability to inspire followers. I’ve heard it said that when Grothendieck walked into a room, you might have had no idea who he was or what he did, but you definitely knew you wanted to devote your life to him.

Krugman Shows How Consumption Taxes Raise and Lower Price Inflation

Back in 2012, some people were worried that rising price inflation in the UK meant that the Bank of England should tighten. But Krugman explained why that was wrong:

But, say the small-[output]-gap people, if Britain is deeply depressed relative to potential, we should be seeing deflation, whereas there’s actually inflation. Is this a decisive argument?

Well, the great bulk of UK inflation these past few years reflects one-off factors: VAT increases, commodity prices, and import prices. Domestically generated inflation is low, and headline inflation is declining too. [Bold added.]

Everyone got that? Krugman was saying that Britain’s increase in the Value Added Tax (VAT) contributed to a spike on headline price inflation, so it could safely be ignored and there was no need to tighten.

Now regarding Japan, Krugman gave his advice right to the Prime Minister:

With a handful of aides and secretaries present at the reception room on the fifth floor of Abe’s residence in the Nagatacho district southwest of the Imperial Palace, Krugman began by praising Abenomics, describing how much he respected the program to revive Japan after 15 years of deflation, Honda said.

The only problem was the sales tax, Krugman said, according to Honda. Honda, Hamada and another aide, Eiichi Hasegawa, kept quiet. Honda says that by the end of the meeting, he was convinced Abe would decide on postponement.

Hamada, who had advised Abe on his pick for Bank of Japan governor, said that “Abe listened to Krugman’s view very carefully.” Hamada said in an interview Nov. 18 that “he probably helped the prime minister make up his mind.”

Abe himself highlighted his discussion with Krugman when speaking on the national public television broadcaster NHK three days ago.

Escaping Deflation

“He said we should be cautious this time in raising the sales tax and if we weren’t it would break the back of the economy,” Abe said. “He said if that happened, we wouldn’t escape deflation, it would be uncertain whether we could revive the economy and repair the nation’s finances. I think that’s the case.” [Bold added.]

So Krugman was urging for the continuation of stimulative fiscal policies, because increasing the sales tax would lead to (price) deflation.

It looks like a general consumption tax either raises consumer prices or reduces them, based on what the answer needs to be to justify the extension of Krugman’s policies.

Recent Comments