Murphy to Be on Robert Wenzel Show

Next Sunday (not tomorrow), January 13. We’ll be discussing Krugman/DeLong and other things, no doubt. In case you have never heard his interviews, Wenzel is a pitbull.

Thoughts on the New Budget Deal

==> Scott Sumner and Steve Landsburg are none too happy.

==> David R. Henderson takes a different perspective.

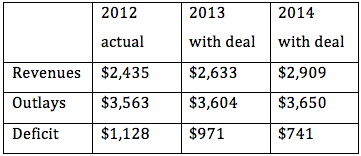

==> I come down on the side of the whiners in this IER post, though I understand what David is saying. (I think we’re mostly just disagreeing about what the relevant baseline should be. Compared to 2012, this deal is bad, and compared to the possibilities of genuine reform, it’s awful. But David is comparing it to the “fiscal cliff” scenario.) Here’s the money table I calculated, because the CBO did everything relative to the fiscal cliff baseline, which turned it all into huge tax cuts. No, compared to 2012, there are tax hikes. To wit:

Those figures are in billions. So, according to the CBO’s own projections, I commented in the following way:

[R]elative to Fiscal Year 2012 (which ended last September), in Fiscal Year 2013 the budget deficit will fall by $157 billion. This will be achieved through (a) a spending increase of $41 billion, and (b) a revenue increase of $198 billion. Some of the projected revenue increases are due to assumptions of economic growth, rather than tax rate hikes per se, but even so, the fact remains that under the new budget deal, the government is still going to fleece the taxpayers of even more money, while ramping up its spending. To top it all off, the projected deficit will still be just about a trillion dollars.

And think back, everybody, to when those fiscally conservative Republicans OH SO RELUCTANTLY gave in on the debt ceiling hike, back in 2011. Remember all that drama, everyone? When the credit rating got reduced? Here’s Boehner back then:

“An increase in the debt limit without major spending cuts will hurt our economy and destroy jobs,” Boehner said in a statement. “A credible agreement means the spending cuts must exceed the debt-limit increase.”

As I pointed out at the time, the Republicans clamoring for a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced budget, etc. are just putting on a show. All they had to do was not raise the debt ceiling and we would have automatically had a balanced budget requirement.

Instead, they went along with raising the ceiling, but put in place a committee–why, a super committee–to give all sorts of expert recommendations, and if those wily Democrats didn’t listen, why, there would be massive, draconian, across-the-board spending cuts…

…which they just avoided, by simply voting not to implement them. (And remember, the cuts would have meant a $9 billion reduction in federal spending in 2013.)

Why Aren’t There More Libertarian Girls?

Oh wow, this issue is exploding. Tom Woods expresses his feelings, and Bryan Caplan weighs in. In case you haven’t seen it, this is the video that annoyed Steve Horwitz and Sarah Skwire:

I am going to offer some quick thoughts. But first, a disclaimer: I am not going to keep writing “in general” or “for the most part” or “have a tendency to.” Obviously, this post will be full of sweeping generalizations. Don’t stereotype-shame me in the comments!

==> I rushed to Julie’s defense, not because I care about the particular issues over which others are arguing, but because (a) I’m her “Facebook friend” so I automatically was defensive and (b) I know what a pain it is to make videos like that. If you’ve never done it, you really have no idea. It would take me probably 6 hours to get something approximating the above. Oops, was your iPhone turned on? Well you gotta do it all over, because now there’s a buzzing in the audio. So, knowing how much effort she is putting into these things, and seeing exactly the little details and tricks she uses to build up her fan base, it is crazy when I was reading comments on FB etc. from people making completely asinine “suggestions” that would ensure no one watches her videos again.

==> Julie is cranking out videos that consistently get more than 10k views, and she talks about “the Budget Control Act of 2011” and “Title IX.” She makes it cool to rip on Republicans for being for “small government” and yet freaking out over defense cuts. If you have never worked in a Think Tank environment, you don’t undersand how important that is. There could be a bunch of people all secretly thinking that, but if a few loudmouths set the tone about “that wuss Obama weakening our national defense!” then they’ll keep quiet. That’s why I am so happy with her video series.

==> The people saying, “I would never send that video to my non-libertarian friends!” are totally missing the point. This video is aimed at LIBERTARIANS. That’s why at the end she says her strategy is “how we win.”

==> If you say, “OK Bob, but then why the rant about the big purse? Why did she put lipstick all over her face? Why doesn’t she just read from cue cards with a stick up her butt?” I refer you again to her Views.

==> Julie is part of a broader trend that delights me. People are making it cool to talk about politics and economics. That’s why I adore Jon Stewart. If you told me in 2000 1998 that a comedian would have a very successful show, largely based on running clips of Fox News and making fun of speeches taken from the Congressional floor, I would have said you were nuts. Just like, if you had told me I’d one day be giving a talk at an event in Nashville with a bunch of musicians who hated the Fed, and where there were 23-year-olds smoking pot in their car beforehand listening to a black guy’s remix of Ron Paul speeches, I would have really thought you were nuts.

==> Right now, for whatever reason, it is cool in our culture to be a progressive. That’s why Matt Damon is being hailed for his anti-fracking movie, whereas Clint Eastwood is mocked for his views. Since libertarians (in our minds) are actually the ones who “know the street” and have the inside scoop on rich guys screwing everybody over, we should be the intellectuals to whom the cool kids turn when they want to learn how the world works. But they don’t trust us right now, because we are boring and out of touch.

==> Having said all that, I actually don’t think this issue–i.e., the need to make libertarianism cool in the popular culture–has much to do with girls not being in the movement. That I think is more explained, by the fact that girls don’t like to argue as much as guys do.

==> Lots of guys like science fiction, and some girls do too. But if I post on my Facebook status, “Who would win in a fight? The Enterprise (Galaxy Class) or a Super Star Destroyer?” it is going to be all guys, except for an occasional girl who makes fun of us for being such dorks. Notice, if I said, “Who could provide the most assistance to a space station with a flu outbreak?” no guy would care. But when I make it about a fight, now we’re interested.

==> So, right now libertarianism as a movement is like my question about the Enterprise vs. the Super Star Destroyer. “Suppose you had a fractional reserve bank versus a 100% reserve bank in a world with no government. Who wins?” Hell yeah, I’m going to make lifelong enemies debating that question. But most girls are going to think, “You guys are dorks.”

==> I think it would be interesting to study Marxism, because there are clearly sectarian squabbles there, but there are a bunch of women in it. So somebody explain that to me. I am quite sure I’m hitting something important above, but it’s not decisive since I can’t explain Marxism.

==> Last point: Say I’m right or wrong, but this is why I “make such an ass” of myself on the Internet. Sometimes I get the impression that certain critics think I got drunk and accidentally posted a video of myself in the bathroom taunting Krugman. Maybe that’s a dumb strategy, or maybe it’s brilliant, but please spare me the lecture, “Bob, don’t you realize that you don’t sound like a stuffy academic? Why would Harvard invite you to guest lecture next year with this video floating around?” Give me a break.

Inside a Mob Family

I was listening to this Fresh Air interview with the son of mobster Frank Calabrese. The interview was from 2011 but Frank Sr. apparently just died on Christmas, so they re-broadcast it. It’s pretty good stuff; there are details about loan sharking and killing a guy who is wily, etc. The mob movies are always fun to watch, but I like to actually hear accounts from real mobsters about how that world works. Here’s a taste where it differs from the stereotype:

JR.: OK. In Chicago, we call it juice loans, and a juice loan is a high-interest loan that’s not through a bank or a credit card company. And you’d get it on the street, preferably from somebody like my dad or somebody from organized crime. In New York and some of the East Coast cities, they’d call it vig. So it’s just a term that we use for juice.

DAVIES: So who were your customers? Who would borrow from you?

JR.: You know, we had all kinds of customers. A lot of customers were degenerate gamblers that couldn’t pay after they gambled that week. So we’d put them on juice right away. Or they were businessmen that needed some quick cash and didn’t want to show it.

We used to have hundreds of guys on juice, some for as little as $100, some for as much as $100,000. And my father was – he taught me a lot of good stuff in that business because a lot of people would say: Well, if you don’t pay, you’re going to get your legs broken. And my father didn’t look at it like that.

What he looked at was if I break the guy’s leg, and it’s going to scare him, how is he going to pay? So he’d always figure out different ways and show us different ways to present to the juice loan customer if he couldn’t pay.

Say a guy had $1,000 and he was supposed to pay $50 a week, and he couldn’t, he couldn’t pay that $50 a week – and it was only interest. Well, what we would do is – my father would double the amount that he owes to $2,000, and he tells him: OK, you pay $10 a week, but you’ve got to pay every week, and that whole $10 comes off the $2,000. So he’d never try to back guys in a corner, if he could.

And then the stuff everyone wants to hear about:

DAVIES: You know, it’s – you’re probably a free man today because you never actually killed anybody, but there was this one occasion where it could have happened, John “Big Stoop” Fecarotta. Do I have the name right?

JR.: Correct.

DAVIES: Yeah. Now, why was that different? What was your role there?

JR.: OK, I was – I had bought into everything at that point. And you know, I was ready to follow my father no matter what. Whatever he said, I would do. The problem was, John was an old-time gangster. And he was smart. He carried a gun on him all the time, and he could catch what we call plays. If somebody was up to something, he could catch on real quick.

And so while we were practicing and coming up with the way it was going to go, it was going to go – my father was playing John Fecarotta in our little role, and my uncle was sitting in the passenger seat. And then I would sit in the backseat, and then I would shoot John in the back of the head.

DAVIES: So they were setting this up so that you were going to actually shoot this guy, right?

But rather than read the transcript, if you are interested in this, I think you should listen to the interview. It gives you more insight to hear the guy actually talk.

I think libertarians tend to be “into” mob stuff, partly because the kind of person who studies the State with morbid fascination should also enjoy analyzing organized crime families. Here’s my review of Diego Gambetta’s economic analysis of the Sicilian mafia, which touches on Rothbard.

“Token Libertarian Girl” on Fiscal Cliff

Julie Borowski put this video up in mid-December, but I just saw it. I was perusing her videos after Steve Horwitz (and Sarah Skwire) sent her to the time-out corner for her most recent video (not the below one).

Julie’s big-picture objective is to make libertarian ideas more appealing in the popular culture. I think the above video is a great example of what she’s trying to do.

Potpourri

==> I want to call your attention to a major UPDATE I made to my response to DeLong/Krugman, inspired by Nick Rowe’s thoughts on macroeconomic disputes.

==> Justin Merrill makes some good points about Cantillon Effects. One thing I had meant to mention myself: The people objecting to the “simplistic” Austrian critiques love to say, “Hey you morons, it’s not like Bernanke is literally handing out money to the bankers. He’s doing an asset swap!” But no, not in the case of paying interest on excess reserves. That is a huge income flow–what I guess would be “fiscal policy” in Scott Sumner’s framework–to the banks, that would be very much appreciated by any other industry.

==> David Glasner (quoted by Callahan) has a nice take on the “efficient markets” hypothesis.

==> I stumbled across this a few weeks ago (honest! This isn’t about the Krugman debacle) and thought it was interesting. Russ Roberts quotes from a Keynesian apologist explaining what went wrong with the WW2 forecasts.

==> At IER, I discuss the funny reaction to the supposedly good news that the US is predicted to become oil independent.

==> Gene Callahan gives a good compilation of smart guys who apparently never read the crushing arguments of Christopher Hitchens. Also this.

==> Tom Woods takes down the modern Greenbackers.

==> David R. Henderson and Scott Sumner clash over taxes.

Learning From Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman

[UPDATE below.]

Rather than have a long series of posts discussing the fallout from my (price) inflation bet with David R. Henderson, I decided to do one comprehensive reply to Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman. I had toyed with not even responding, but two things ruled that out: (1) This isn’t a case of two guys challenging me on some academic point; they are publicly impugning my character. (2) My supporters have pledged (as of this writing) more than $81,000 that will go to a food bank in NYC if Krugman ever debates me on business cycle theory.

If I just walk away from this incident, they might worry that Krugman is holding a trump card against me, and their enthusiasm for promoting the debate will wither. So to be clear, I would still love for Dr. Krugman to publicly debate me on Keynesian vs. Austrian business cycle theory, and if he ever did try to bring up this inflation bet, I have lots I can say in reply, as I discuss below. Because this post will be long, I am organizing it into sections.

I. The Pot Calling the Kettle a Pot

It is simply astounding to me that I am being accused of ideological dogmatism and a refusal to see the merits of my opponent’s position by these particular gentlemen. Brad DeLong is notorious for deleting people’s comments on his blog who say things that disagree with him. This is not an urban legend. It’s happened to me, to Mario Rizzo (you know, that bomb-thrower Mario Rizzo), and other people who are being completely courteous and on-topic. DeLong also has a running series where he nominates the “Stupidest Man Alive” (here’s an example), and he routinely mischaracterizes his opponents’ positions in arguments ranging from economics to politics to philosophy–for example, implying someone was a creationist (who in reality was an atheist) but not actually saying so explicitly, proving that DeLong knew exactly what he was doing. (If you really want a fun anecdote, here I explain DeLong’s outrageously selective reading from Herbert Hoover’s memoirs.)

Paul Krugman, for his part, tells us, “Some have asked if there aren’t conservative sites I read regularly. Well, no. I will read anything I’ve been informed about that’s either interesting or revealing; but I don’t know of any economics or politics sites on that side that regularly provide analysis or information I need to take seriously. I know we’re supposed to pretend that both sides always have a point; but the truth is that most of the time they don’t.” Beyond that, Krugman routinely dismisses his critics as idiots or liars who literally don’t understand intro macro, even if they are expressing a stance he himself held within the previous 15 years.

Let us not forget what the former New York Times Ombudsman Dan Okrent had to say about his professional dealings with Dr. Krugman. He said that after some serious haggling, he once got Krugman to “reluctantly” issue a correction on something in one of his columns, and then Okrent comments on that word, “I can’t come up with an adverb sufficient to encompass his general attitude toward substantive criticism.” (I can find people quoting Okrent, but the links to the original seem broken.) But don’t take Okrent’s word for it; just go read Krugman’s blog for a week, and then you tell me if he’s the kind of guy who freely admits when his critics had a good point on something.

So in summary, I am being hauled in front of a tribunal, being accused of dogmatism and an unwillingness to see when my opponents have the better of me…by Brad DeLong and Paul Krugman?! Can this really be happening? I’m hoping Rod Serling can make an appearance and shed some light on these events.

II. Austerian #1 vs. Austerian #2: No Matter Who Loses, Krugman Wins

I made a bet on official CPI and lost. Brad DeLong wants me to announce on my blog, “I have been totally wrong, about everything. I am closing down this weblog for five years to avoid misleading readers while I intellectually retool. You will find me sitting at the feet of Paul Krguman, chanting ‘om mani padme hum’ until I achieve enlightenment.”

But wait a second. I didn’t bet against Paul Krugman, I bet against David R. Henderson. So why wouldn’t I have to sit at David’s feet?

Well, the answer is that David is an “austerian” (in Krugman’s terminology) too. And I don’t just mean if you grabbed him on the street and asked him. I mean, he wrote a study for a DC think tank on how Canada solved its fiscal crisis mostly by actual cuts in federal spending, and he went on John Stossel’s show to preach this message of austerity. That’s the guy who won the bet.

Since David just won a bet, that’s a feather in the cap of his model, and now Brad DeLong has updated his Bayesian priors on David’s worldview, right?

So to summarize, two economists who both have written studies urging fiscal austerity based on the Canadian example (mine here) had a bet. When one of the austerians lost–which had to happen, since ties were impossible–DeLong and Krugman thought this proved austerity doesn’t work.

(In related news, I am trading public trash talking with Chris “Ron Paul’s Freaking Giant” Lawless on Facebook for a game of P-I-G in basketball at a conference in the summer. When one of us loses, will Rudy Giuliani say, “Aha! I was right about 9/11 after all!” ? If so, Chris and I will cancel.)

III. Price Inflation Has Virtually Nothing to Do With Austrian Economics in General, and Truly Has Nothing to Do With Austrian Business Cycle Theory

When explaining why Christina Romer’s notorious unemployment forecasts have no bearing on Keynesian models, but my price inflation forecast blows up Austrian economics, Krugman writes:

[I]t’s really important to distinguish between fundamental predictions of a model and predictions that an economist happens to make that don’t really come from the model….[T]he unfortunate Romer-Bernstein prediction of a fairly rapid bounceback from recession reflected judgements about future private spending that had nothing much to do with Keynesian fundamentals, and therefore sheds no light on whether those fundamentals are correct.

In short, some predictions matter more than others.

Beyond that is the question of how you react if your prediction goes badly wrong.

The fact is that while Keynesians predicting a fast recovery weren’t really relying on their models…

As Alex Padilla quipped on Facebook, if Romer wasn’t using her model to generate the unemployment forecast, then whose model was she using?

But joking aside, we all get the point Krugman is making here, and it’s a valid one. That’s why I’m going to say it applies to my price inflation bet, a lot more than it applies to someone who was saying we needed the Obama stimulus package because it was going to raise employment.

Simply put, my price inflation wager has nothing to do with Austrian business cycle theory. Mario Rizzo spells it out here, and to his credit Daniel Kuehn (who is a huge fan of Krugman and DeLong) also gives this claim a fair hearing on his blog. Yes, I screwed up in my bet with David–and possibly with Bryan, we’ll see–but it’s not because Mises and Hayek doomed me.

Really. For example, I just wrapped up on online course on ABCT and the Great Depression. The only point I recall making about price inflation that was directly tied to ABCT, was that Mises had explained before the Crash why Irving Fisher’s policy of stabilizing consumer prices could still allow an unsustainable boom.

Krugman thinks that worries over price inflation are essential to the Austrian position, because:

The prediction that huge increases in the monetary base will cause large increases in the price level, and that big government deficits will cause big increases in interest rates, are more or less inescapable if your model of the economy is one in which recessions are supply-side problems, not the result of inadequate demand.

Yes, that would be true, if other things were equal. But you could have a big reduction in supply (due to a discoordinated capital structure bequeathed by the preceding boom) accompanied with a big reduction in demand, because the financial world is collapsing and everyone rushes to dollars and Treasuries. This wouldn’t mean that throwing trillions of dollars in new money at the problem would solve the underlying real problem, nor would it mean that modest consumer price hikes would prove that some more $100 bills was the solution.

The fundamental problem here is that Krugman is using a very simple macro model, with a few aggregate variables, and he’s trying to spin out implications of the Austrian view in such a world. Well, that isn’t going to work because the Austrian theory relies on heterogeneous capital goods and the role that artificially low interest rates play in distorting the sectors into which investment flows. You can’t really test to see if that theory is right, by using a model that has AD and AS moving around and causing “the price level” to go up or down.

In any event, Krugman is hardly qualified to be telling us the empirical implications of Austrian theory. In his last written response to me, Krugman asked, “Why is there overwhelming evidence that when central banks decide to slow the economy, the economy does indeed slow?” To be clear, Krugman thought this would embarrass the Austrians, who must not have been aware of the peer-reviewed, cutting edge research showing that when central banks raise interest rates, the boom turns into a bust. This would be like asking a Christian, “Well if God loves us so much, why did He send His son?”

The problem here is that Krugman actually hasn’t read much of Austrian business cycle theory. I’m guessing–can’t prove it–that he read somebody else summarizing it. This is why Krugman apparently classified it as a “real” theory, relying on underlying technological considerations, as opposed to Krugman’s demand-based theory. Since the central bank raising interest rates doesn’t burn crops or kill workers, Krugman thinks the Austrians must not be able to explain how changes in money can affect the business cycle.

Anyway, if you want to see me give a point-by-point response to Krugman’s erroneous understanding of Austrian business cycle theory, read this essay.

IV. “Then Why Did You Bet Bob?!”

Because I thought I would win $500, duh.

Here’s the bigger context: Back in late 2008 and early 2009, many analysts–including me–were freaking out about the unprecedented actions that the Fed and other major central banks were taking. (For example, in June 2009 I explained why I thought the real economy would be “in the toilet for a decade” and that I expected “20+ percent price inflation.”) Bryan Caplan thought we were overreacting, and wanted to bet on something specific, so that the inflation-mongers couldn’t just issue vague warnings that might someday come true. Understanding that he had a point about non-falsifiable hysterics, I bet Bryan $100 in 2009 that by January 2016, official CPI would rise 10% year/year.

Just to be clear–since these two points come up in every comment section on the issue–I was aware at the time that there are serious problems with the way the government calculates CPI, and I knew that if I won the bet, I would be getting paid in weaker dollars than if Bryan won. (I understand that rising prices means a weaker dollar, yes, I do understand that.) Official CPI inflation rose at almost 15% yr/yr at one point in the early 1980s, and since I think what Bernanke has done will ultimately be worse, I am thinking the government won’t be able to get away with reporting less than a double-digit rise.

Seeing my bet with Bryan, David wanted a piece of the action, but he wasn’t comfortable giving such a big window. So he wanted to shorten the horizon from January 2016 down to January 2013, and bump up the amount from $100 to $500. Obviously I was less confident about this bet than the one with Bryan, but I still thought I would win it so I said sure.

V. What Went Wrong?

I’m not sure yet, which is why I haven’t performed seppuku as DeLong insists. I realized that there were a lot of excess reserves when I made the bet with David, but it was also true that M1 had risen strongly since the onset of the crisis (presumably as people fled to very liquid assets). The big thing is that I did not, and do not, trust Bernanke when he tells us there will be a gentle unwinding of the Fed’s balance sheet, and that if things ever started getting out of hand he has all sorts of “exit strategies.” I thought other investors would eventually agree with me that the Fed was simply printing money to buy time and temporarily stave off disaster, and they’d head for the exits. Back in late 2009, I was sure enough that this would happen within two years that I bet $500 on it.

Well, it hasn’t happened yet, so what does that mean? Are we stuck in a dollar and Treasury bubble that is taking longer to pop than I thought? Or have I been “completely, comprehensively, unmistakably, fundamentally, fatally, totally wrong,” as Gentle Brad puts it?

I don’t know, of course, and none of us can, until the bubble bursts or the Fed unwinds its balance sheet with no major hiccups. So I haven’t been writing much on price inflation in a while, and when people ask me in radio interviews etc., I have been prefacing my remarks with, “Let me just admit, I thought this was going to happen already and it hasn’t, so take my analysis with that caveat…”

VI. Learning From My Mistakes, DeLong and Krugman Style

It’s true, Krugman and DeLong have changed their minds on plenty of issues over the years. For example:

(A) Krugman’s notorious 2002 call for Greenspan to replace the bursting tech bubble with a housing bubble. Then, just to be sure there was no misunderstanding, read the 2006 exchange with a reader to see Krugman’s nuanced view of the matter. Having had to explain this extremely unfortunate statement many many times, Krugman has learned to no longer make flippant remarks about the Fed creating an asset bubble to prop up aggregate demand.

(B) In the late 1990s Krugman thought that there was only dubious theoretical justification, and perhaps not a single historical example, for the view that a large fiscal stimulus could rescue an economy from the liquidity trap. Krugman actually used the term “Krugman solution” to refer to a purely monetary approach. Early in the 2008/09 crisis, Krugman championed fiscal policy. Then later, he came back to monetary. In a similar vein, DeLong in early 2009 said monetary policy had “shot its bolt” and was championing fiscal policy. Eventually though he acted like he’d been bosom buddies with Scott Sumner all along.

(C) When it comes to understanding/forecasting the bond markets, Krugman and DeLong have both admitted mistakes. Read what is now a laugh-out-loud funny article from Krugman freaking out about the US government’s debt and the imminent attack from bond vigilantes back in 2003, and in this piece DeLong explains that he has “gotten significant components of the last four years wrong…federal funds rates at zero I expected, but 30-Year US Treasury bonds at a nominal rate of 2.7% I did not.” (HT2 EPJ)

And there are plenty more I could give you. So yes, it’s true: Reading DeLong and Krugman is like watching a ballet, with one dancer named Fiscal and the other Monetary, and at any moment you’re not sure who will be leading the other. But the title of the ballet is, “The Free Market Needs a Genius Like Me to Fix It.”

Krugman and DeLong have tweaked their views over the years, but they are still interventionists. There is literally no empirical outcome that would ever make either of these guys say, “Oh my gosh, I have been totally wrong about the need to prop up Aggregate Demand. I am going to send Peter Schiff an apology.”

So when Krugman says that his Keynesian colleagues have engaged in “soul searching,” this is the kind of thing he means. They’re not questioning the core premises at stake here. Look at how he handled my question about Christina Romer: He didn’t even entertain the possibility that it was the Obama stimulus package that made the economy suddenly “get worse than we realized” in early 2009. No, we all just know that a big deficit creates more jobs than would otherwise be the case, and so if Romer’s forecast was off, well it was because she plugged in the wrong baseline.

In the spirit then of being as flexible and data-driven as DeLong and Krugman, let me report on how much I’ve changed my own views in just the last few years:

(D) I used to think that unemployment benefits and refundable tax credits weren’t that big a deal in explaining the sluggish recovery, but the empirical work of Casey “Poverty Should Have Risen” Mulligan has made me change my mind.

(E) I used to think that if we were going to have a Fed that did something, it might as well lock in a fixed price of gold. But now I’ve been convinced by other Austrians that this would probably be a bad idea, because the Fed officials would just go off the new gold standard the next time it became really onerous, thus discrediting the reform. If we’re going to push for a massive change, might as well go for complete abolition of the Fed.

(F) I used to think–and even wrote it up in my textbook for young readers–that the only way a government debt could impose a burden on future generations, was through the crowding out of physical investment in private capital goods. But then Don Boudreaux and Nick Rowe showed me that government debt can allow the present generation to effectively transfer wealth from their descendants in a much more direct way. Thanks guys, you made the scales fall from my eyes.

(G) Relevant to my inflation bet, I’ve learned something important: The urgent task isn’t to abolish the Fed, but rather to abolish the IRS. Price inflation wasn’t the clear and present danger I thought it was back in 2009. My priorities have altered. First the IRS, then the Fed.

Now that I’ve exhibited the analogous flexibility in my policy views that DeLong and Krugman possess, I’m sure they’ll let me join their League of Distinguished Scientists, don’t you think?

Ha ha, of course not. They get to “change their minds” by tweaking how they want the government to redistribute income and create new money. But when I get something wrong, they want me to drop my drawers, bend over, and ask, “May I have another stimulus, sir?”

VII. Krugman Wins Price Inflation, But Loses a Bunch of Others

Finally, let me remind people of some issues directly related to diagnosing the cause of the recession–“sectoral imbalance” versus “general shortfall in demand”–where Krugman was simply wrong:

(A) In late 2008 Krugman argued that the housing bust had little to do with the recession, because the latest BLS figures showed that unemployment at the state level bore little relationship to the declines in home prices across the states.

However, I pointed out that looking at year-over-year changes in unemployment at the end of 2008 was hardly the right test. If we looked at changes from the moment the housing bubble burst, then five of the six states with the biggest housing declines were also in the list of the six states with the biggest increases in unemployment.

(B) Later, Krugman once again thought he had dealt the readjustment story a crushing blow when he pointed out that manufacturing had lost more jobs than construction. I pointed out that this too wasn’t a valid test, because manufacturing had more workers to begin with. When we looked at percentage declines, then construction did indeed crash more heavily than manufacturing. Furthermore — and just as Austrian theory predicts — the employment decline in durable-goods manufacturing was worse than in nondurable-goods manufacturing, while the decline in the retail sector was lighter than in the other three.

There are other examples–how about Krugman telling people gold went up (as the “inflationistas” would have predicted) not because of Bernanke, but because of Glenn Beck?–but the above two suffice to make my point. I didn’t pick out the above two tests of our theories; Krugman did, and (I argue) he botched the tests. When you run the tests in what is surely a more appropriate way, Krugman’s theory no longer comes out on top, and moreover, his theory can’t really explain the results the way the Austrian explanation easily can.

So feel free to send those links to Dr. Krugman, and let’s see how much soul-searching they provoke.

UPDATE 1/3/2013:

After reading an excellent post by Nick Rowe explaining why there are no controlled experiments in macroeconomics, I realized there was one crucial point I forgot to make in my original post, above. So let me append one more section, and then hopefully we can all move on with our lives.

VIII. If I Happen to Win the Bet With Caplan, Krugman Will Still Be “Vindicated”

Suppose that by January 2014 (well ahead of schedule for what I need), the dollar has fallen strongly against other currencies, short-term Treasury yields have risen to 7%, headline CPI has risen year/year by 11%, and the national unemployment rate has moved up to 9.3%. So Bryan cuts me a check for $100, my fans have multiple orgasms, and then what does Krugman write on his blog? Does he say, “You may have won this time Murphy, but I’ll be back, I’ll be back!!”

No, that’s not at all what he would write. Rather, it would go something like this:

Oh my. It seems the childish blogger at ZeroHedge–who likens himself to a paranoid schizophrenic movie character, which is actually quite appropriate–is chortling with glee because an austerian won a bet about inflation, and it so happens that it’s the same guy who earlier lost a bet (upon whom Brad DeLong and I heaped justifiable scorn). Even though the austerians and ZeroHedge folks have been totally, utterly wrong for five years straight–see here, here, and here–they now want to argue that I should quit blogging and just play golf, or something.

Um, no. As anyone who has actually, you know, read my blog would understand, I never said the US would forever have modest inflation. Indeed, literally the same week I took this austerian down for losing his first (and bigger!) bet, I explained that inflation would one day become a real threat.

I know the austerians don’t understand the liquidity trap, but the rest of us serious analysts do. I have always said that inflation would remain subdued so long as we were in the liquidity trap. Since the Fed has been steadily raising rates since August, we are clearly no longer in the liquidity trap, and now we return to the normal framework where the austerians won’t make utter fools of themselves.

But here’s the thing: It’s not merely that the IS/LM framework once again comes through with flying colors. In terms of policy prescriptions, the Fed and government have been doing exactly what the austerians have been screaming for, all along. The Fed has been raising interest rates–just like the Hayekian groupies want, to avoid those dastardly “artificially low interest rates”–and as part of the budget deal from late February, discretionary spending has been trimmed by a whopping $850 billion. And yet, unemployment went up. Imagine that–contractionary policy is contractionary. Who knew?

If you doubt that Krugman would write something like the above, then you need to become more empirical. And just to reiterate my main theme here in this final section, Krugman would be justified in so arguing. Economics is not about unconditional forecasts, rather, its core propositions or “laws” are couched in ceteris paribus terms. Economic theory gives us a framework for interpreting the world. So it’s not that Krugman the Keynesian is wrong for being able to explain his way out of any predicament, rather it’s that he is fooling himself for thinking he is a “scientist” as opposed to those medieval Austrians who talk about a priorism.

Last thing, somewhat related: I got burned because I went out on a limb and locked myself into a specific CPI range by a specific date. Obviously, that was a dumb thing to do, both in terms of my bank account and reputation. But Krugman is able to run victory laps partly because he himself has a humongous “error bar” in his stated views. For example, over the last few years Bob Wenzel has comedically pointed out every time Krugman warns of deflation. So: I warned of serious price inflation and was wrong, and mocked accordingly. Krugman for years has been saying price deflation was the threat, that hasn’t come to fruition, and he is hailed as Nostradamus.

Yes yes, of course Krugman and his fans can explain away why his warnings of deflation didn’t pan out. Bernanke saved the day, blah blah blah. But they should then not get so upset when I and my fans explain away my botched price inflation warnings. That’s really the issue here: Guys like Nick Rowe, Russ Roberts, and me understand full well just how hard it is to remove ideology from the estimates of “multipliers” and such, whereas Krugman, DeLong, et al. don’t realize how much they are infused with confirmation bias every time they pick up a keyboard.

Krugman-DeLong Smackdown

Oh my gosh, the Great One has jumped in as well. And perhaps he will bring in enough extra ad revenue to pay my obligation to David?

This part of Krugman’s post made me literally laugh out loud, such that people in Barnes & Noble gave me the stink eye: “The fact is that while Keynesians predicting a fast recovery weren’t really relying on their models, the failure of that fast recovery has nonetheless prompted quite a lot of soul-searching and rethinking.”

But joking aside, Krugman at least gave a good reply to my last post. In other words, Krugman is at least trying to offer a rationale for why the people wrong about (price) inflation since 2008 should be tarred and feathered, whereas Christina Romer (for example) shouldn’t have her credibility harmed because of her bogus argument for the stimulus package.

I really have other work I have to be doing today, and then I’m traveling all day tomorrow, so it might be a few days before I respond to this.

Recent Comments