Potpourri

I’m going on a long trip so not sure what blogging will be like for a few days… In the meantime:

==> David Glasner has a nice Alchian post. Man, there were some heavy hitters at UCLA back in the day. I used Jack Hirshleifer’s textbook when I taught intermediate micro. It had the cool diagram showing how you could turn a 3-dimensional utility mountain into a 2-d set of indifference curves. Ah, Mises would be proud of me.

==> Want more on Alchian? Sure.

==> David R. Henderson gets sarcastic about foreign policy.

==> Speaking of foreign policy, check out these thoughts on the drone debate.

==> Daniel Sanchez doesn’t turn the other cheek when Krugman calls us a cult.

==> Many of you will find econ giant Ed Prescott’s 2006 list of “myths” to be amusing.

==> I really like Garett Jones’ blogging style. Like me, he comes up with an odd take on issues, but then builds up a pretty specific example to illustrate exactly what he means. Once he writes a One Act Play talking about fiscal multipliers, we’ll know he is ready for the Jedi Council.

==> I’m such a model for Catholics.

==> The other R. Murphy has some good points on the minimum wage debate.

==> David R. Henderson wants you to “respect my authority!”

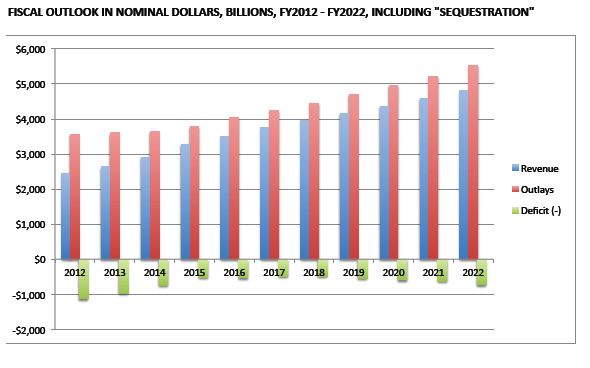

Sequestration Analysis

Man the CBO makes it tough to figure out what absolute spending levels will be. Their analysis of the December/January budget deal–the one that spared us the horrors of the fiscal cliff–is couched as changes relative to the then-current baseline. So I took that as the August 2012 CBO Outlook, and constructed the following:

I have a more comprehensive analysis that may be published soon at a different site; I’ll link it from here when that happens. But in the meantime, I wanted to reward diligent Free Advice readers with a sneak peak.

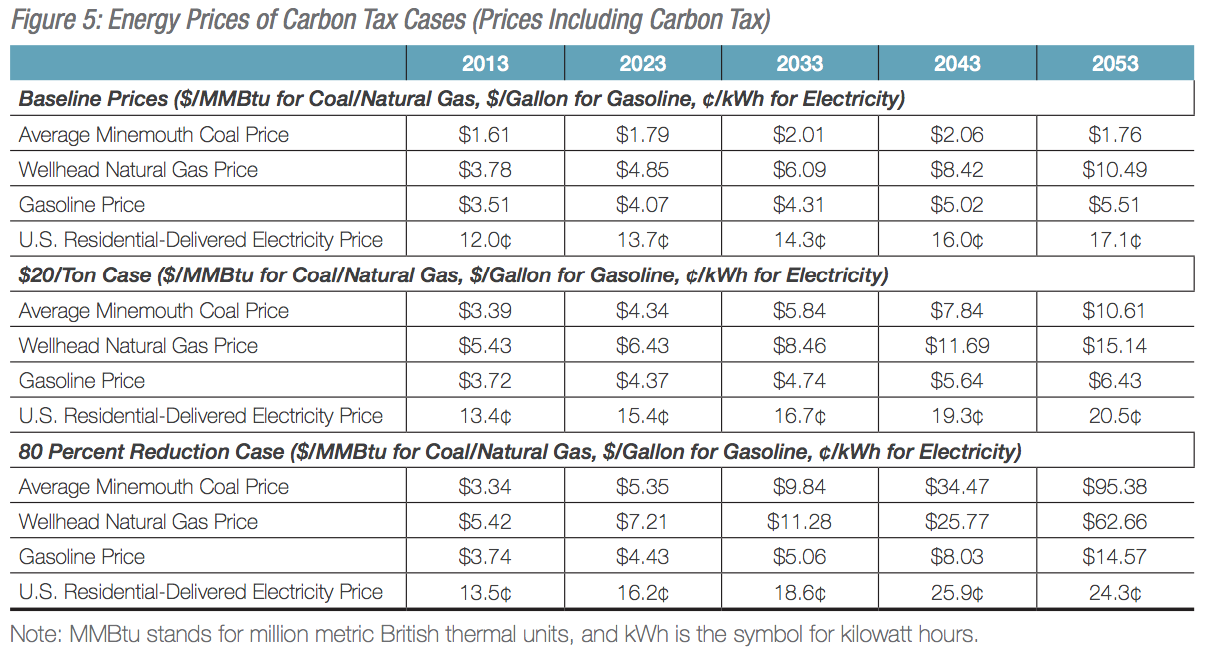

New NERA Study on Two Carbon Tax Scenarios

NERA Economic Consulting is out with a very nice study on two carbon tax scenarios. I know this modeling team (well, at least the lead author) and I think they are very nuanced in their analysis; if you scroll through the paper you can see they explain exactly what their charts are saying, etc. This is an above-average study in this genre, just in terms of its attention to detail and transparency.

Here’s a money chart:

As I explain in an IER blog post discussing the study:

[T]he 80% [emissions] reduction case shows drastic increases in electricity and gasoline prices in the coming decades, should the US government seriously try to meet the emission reduction targets that many groups are proposing as “sensible climate policy.” By 2053, the NERA study anticipates residential electricity prices having risen 42 percent relative to the baseline, and gasoline pries at a whopping $14.57 per gallon (compared with $5.51 in the no-tax baseline, because of rising crude market prices).

And of course, if someone is interested in the coal industry—forget about it. The price of coal in the high-tax scenario eventually ends up being 54 times higher than it would be without the carbon tax. Such a punitive tax rate will obviously destroy the coal industry, which after all is one of the stated objectives for those who want to drastically reduce US emissions.

Ironically, I conclude by pointing out that the NERA study understates the economic damages from their hypothetical carbon tax scenarios:

The most obvious reason is that the NERA study assumes the carbon tax receipts will be used to either (a) reduce the federal deficit from what it otherwise would have been, holding spending constant and/or (b) reduce other taxes. In terms of supply-side economic analysis, given that there is going to be a new carbon tax, then the very best things one could do with the revenues is use them to cut other tax rates and/or to make the deficit smaller, so that the government doesn’t siphon off as much from the capital markets away from private investment.

In other words, NERA’s projections of economic outcomes under the two carbon tax scenarios has the government behaving very responsibly, doing just what a free-market economist would want, given that it was imposing a carbon tax.

In reality, of course, the government won’t keep its spending trajectory the same, (for reasons I explain here) in the presence of hundreds of billions of new annual revenue in the modest scenario, and even trillions of dollars in new revenue in the aggressive case. Specifically, the NERA projections show that the 80% Emission Reduction scenario has the federal government taking in $1.8 trillion in inflation-adjusted revenues by the year 2053 from its carbon tax.

Does anybody seriously believe this flood of new revenue won’t lead to higher federal spending than would otherwise be the case? Note that such spending would include any “transition payments” to help poorer households or certain industries adjust to the new carbon tax, which will surely be part of any politically feasible deal.

I Am Officially in the Twilight Zone: Callahan and Glasner on Sraffa-Hayek

[UPDATE: I’m slightly editing the “exchange” (which are my words of course) between Hayek and Sraffa to make it closer to their actual words…]

It’s a weird situation, I grant you, but I’ve been running around for years saying that the Austrians have never given a good response to Sraffa’s critique of Hayek. (I summarize my views in one of the sections in this paper.)

It’s not surprising that the Austrians haven’t thought much of my view. But what is freaky is that Gene Callahan and David Glasner think I’m wrong too.

But wait, it gets better (worse). Here is my summary of the Hayek/Sraffa debate (on this point of “own rates of interest,” I’m not talking about their broader disagreements), with the vocabulary updated to our terminology:

HAYEK:

To avoid causing an unsustainable boom, the monetary authorities should set the money rate of interest equal to the natural rate.The unsustainable boom occurs when the banks charge a money rate of interest lower than the natural rate.SRAFFA: What the heck are you talking about? Outside of the steady state–but even in an intertemporal equilibrium, where there are no arbitrage opportunities–there are as many “natural rates” of interest as there are goods.

HAYEK: I know that, I’m not stupid.

SRAFFA: So…when you say the

centralbanks should set the money rate to the natural rate, I guessit hasthey have to set the nominal rate of interest equal to different numbers, simultaneously?HAYEK: OK, well, what I’m trying to say is…

Now in fairness to Hayek, he really did get the problem, and he gave a hint of an answer. But that was it. I claim that no one since has ever followed through, certainly not Lachmann who didn’t see the problem. (I tried to sketch what a more comprehensive answer would look like, in my paper that I linked in the beginning of this post.)

OK so assume for the sake of argument that I’ve correctly summarized Sraffa’s criticism. Look at how Glasner and his co-author think they’ve exonerated Hayek:

However, as Ludwig Lachmann later pointed out, Keynes’s treatment of own rates in Chapter 17 of the General Theory undercuts Sraffa’s criticism. Own rates, in any intertemporal equilibrium, cannot deviate from each other by more than expected price appreciation or depreciation plus the cost of storage and the service flow provided by the commodity, so that the net anticipated yield from holding assets are all are equal in intertemporal equilibrium. Thus, the natural rate of interest, on Keynes’s analysis in the General Theory, is well-defined, at least up to a scalar multiple reflecting the choice of numeraire. However, Keynes’s revision of Sraffa’s own-rate analysis provides only a partial rehabilitation of Hayek’s natural rate. Since there is no unique price level in a barter system, a unique money natural rate of interest cannot be specified. Hayek implicitly was reasoning in terms of a constant nominal value of GDP, but barter relationships cannot identify any path for nominal GDP, let alone a constant one, as uniquely compatible with intertemporal equilibrium.

The way I am reading that, it is saying, “Sraffa was wrong to think Hayek had given no guide on how the central bank should set the nominal rate of interest. We can indeed define it, up to a scalar multiple. Really, the problem here is that Hayek didn’t realize there was no unique natural rate of interest outside of the steady state.”

!!!

In other words, they conclude what–I claim–was Sraffa’s original point.

My theory is that it is so mentally taxing for people to work through the relative price change / storage cost stuff, that the 8 people* who have done so since the 1940s think that no one else must have been able to.

* The 8 people being Sraffa, Hayek, Keynes, Lachmann, Gene, Glasner, Glasner’s co-author, and me.

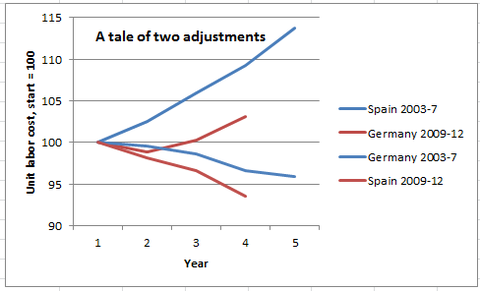

It’s Monday, So Krugman Thinks Labor Costs Hurt Employment

Commenter “Xan” draws our attention to today’s post from Krugman, in which he writes:

A commenter on my last euro post asks a good question: didn’t Germany once have a problem of excessive unit labor costs, which it cured with a protracted squeeze? And in that case, why is it so terrible if Spain is asked to do the same thing?

The answer is basically quantitative. I’d make three points:

1. Thanks to the giant housing bubble, Spanish costs got much further out of line than Germany’s ever did, so the required adjustment is much bigger.

…

Here’s a figure that illustrates that point. According to Eurostat data, German unit labor costs peaked in 2003, Spanish costs in 2009. So here’s what the adjustments looked like in each episode, with blue lines representing the earlier case and red lines the later:You can see just how much harsher Spain’s adjustment is, and how much less help it’s getting from rising wages in the rest of the eurozone. Basically, Germany is refusing to do for Spain what Spain did for Germany in the past.

And the result of all that is incredibly high unemployment.

Now it sure sounds like Krugman is saying that high labor costs make employers less likely to hire workers. Quantitatively, from that chart it looks like having labor costs that are 14% too high, is a problem that will lead to “incredibly high unemployment.”

But when it came to discussing President Obama’s call to make low-skilled American workers have 24% higher labor costs, here’s what Krugman said:

[W]hile there are dissenters, as there always are, the great preponderance of the evidence from these natural experiments points to little if any negative effect of minimum wage increases on employment.

Why is this true? That’s a subject of continuing research, but one theme in all the explanations is that workers aren’t bushels of wheat or even Manhattan apartments; they’re human beings, and the human relationships involved in hiring and firing are inevitably more complex than markets for mere commodities. And one byproduct of this human complexity seems to be that modest increases in wages for the least-paid don’t necessarily reduce the number of jobs.

So what’s the story? Aren’t there human beings in Spain? Do workers there act like bushels of wheat? Won’t it hurt worker morale to see the prices of food and energy go through the roof, while their nominal wages stay flat (Krugman’s preferred solution to the Eurozone problems)? Is there monopsony in the US, but not in Europe?

You almost get the sense that Krugman grabs whatever argument he needs, to justify his preferred policies–a minimum wage hike for the US, more monetary inflation for the ECB. But that’s what the guys at right-wing think tanks do, not Krugman!

A Christian vs. Skeptic on Heaven and Hell

CHRISTIAN: Praise God! He sent His only Son to die for our sins, so that we could have eternal life.

SKEPTIC: That is a repugnant doctrine. Putting aside all the scientific and logical flaws, look at what a tyrant your so-called God is. He is saying that if we don’t worship him, he burns us forever. What the heck is that?

CHRISTIAN: No, you’re looking at it the wrong way. God isn’t sending you to hell for your failure to worship Him or to accept Jesus. Rather, He sends you to hell because you are objectively a sinner. You broke the law many many times during your life, knowing full well what you were doing, and thus He is going to punish you as the criminal you are. However, although He is infinitely just, He is also infinitely loving, merciful, and self-sacrificing. Jesus is willing to take your punishment for you, because He is the best friend you could possibly have. Yet even here, God respects you as an autonomous individual. If you don’t want Jesus’ offer of help–to take your punishment so that you can enter into paradise on His behalf–then God will respect your decision. If you think you don’t need Jesus’ help, and you want to face the judgment of God on your own merits, go right ahead. God will let you choose that door, if that’s what you want.

SKEPTIC: *sigh* OK fine, God isn’t officially torturing you forever, because you didn’t accept his son. Rather, he tortures you forever, because you–what? Ate pork? Didn’t go to church? Said “go*dammit” in anger? Even if you did something that Christopher Hitchens would agree is bad–like you were a serial killer–it is still monstrous that you should get punished for eternity. Whatever happened to punishment fitting the crime? I can’t even believe I’m arguing with you, but you seem like such a fair, rational person, except when it comes to the Jesus stuff.

CHRISTIAN: This is just another great example of how you’re reaching the wrong conclusion, because you’re not being consistent. You will accept one or two things about my worldview for the sake of argument, without taking my entire worldview in one fell swoop to give it a fair shake. You and I have already argued about whether the notion of a Christian God is compatible with Misesian economics. My answer to you then was that God is outside time–He created time as we know it, just like He created space. So it wouldn’t make sense to have God put you in hell for, say, 3 years if you were a serial killer, but only 2 months if you were just an adulterer. There’s no such thing as “3 years” once you’re in the afterlife. It’s just one everlasting moment of total consciousness.

SKEPTIC: OK fine fine, if you believe a guy could walk on water and feed 5,000 people with some fish, I guess it doesn’t shock me that you could say time doesn’t exist in hell. Still: We agree that God set up the rules, right? So what kind of messed up system has a person be in agony when he honestly thought the weight of scientific evidence and rational inquiry, came down on the side of atheism? Why should such a person be subjected to, what you yourself stress, is infinite torment?

CHRISTIAN: I grant you that hell is often portrayed in this manner, like you’re the same guy you were on earth, but now you’re being dipped into a lake of fire. However, suppose that’s just a metaphor to scare you straight. Suppose that what hell really is, is something more like this: After you die, you achieve “total consciousness,” in the sense that you gain a complete understanding of everything that happened in the material universe from the moment of creation until the final judgement. You realize just how inconceivably wonderful life on earth could have been, for all those thousands upon thousands of years of human civilization, had everyone simply obeyed the rules God gave them. But instead of that, of course, people disobeyed. And it’s not just that they broke seemingly arbitrary commands. No, they did things that they themselves knew were wrong, according to their own professed moral code. The difference is, from their elevated perspective in the afterlife, people can see just how damaging their transgressions were. One offense, which seemed minor to the offender at the time, magnified over the centuries into a mountain of total human suffering, in the sense that had the person not committed that teensy weensy violation of his own professed moral code, then millions of humans over the next few centuries would have had much better lives on the margin. So can you imagine what it would feel like, to see just how wonderful life could have been–no wars, no crimes, no broken homes, no sickness in the sense we think of (because you now realize that too is a product of fear, anxiety, poverty, substandard sewage systems, and other things ultimately traced to immoral behavior)–but we humans screwed it up in our ignorant, spiteful pride? And that the person realizes his own role in that? I submit such a realization–which would be eternal, since time no longer passes–would be pure hell.

SKEPTIC: (pauses) Hmm, that’s very clever, I see how you’re trying to turn it around, so that it’s not God punishing you, but you punishing yourself. Let’s ignore that rhetorical trick for the moment. Even if I stipulate everything you just said, why wouldn’t the same perpetual hell ensnare the Christian? After all, you think your actions on Earth are depraved–you know that even now, with your limited knowledge of how human actions relate to each other, and how the “cycle of sin” perpetuates itself. So how does the fact that you said a prayer inviting Jesus into your heart when you were 8, counteract all of the grief and despair that should hit you like a ton of bricks after you die and realize just what a scumbag you were on Earth?

CHRISTIAN: The person who previously acknowledged he was a sinner, and needed the help of Jesus, can handle the psychological shock of seeing the depth of his crimes. He didn’t realize how much of a sinner he had been, but at least he hadn’t fooled himself into thinking he was “basically a decent person” while alive. And since he has accepted Jesus’ gift of salvation and acknowledged that Jesus is God, such a person in the afterlife now stands in the direct presence of an omnipotent Being who is the source of all truth, beauty, goodness, wisdom, mercy, and love. That is such an awesome moment of comprehension that he literally forgets about all of his crimes on Earth; that stuff is no longer important.

There are two possible states in which one can exist in the afterlife. Since there’s no time in the sense we perceive it in this life, these states are eternal. In one state–called “hell”–you are completely narcissistic, focusing on your transgressions and realizing what a fool you had been, over and over and over again, throughout your life. You are filled with an infinite amount of regret, agony, sorrow, and fury at the horrible system that let this outcome occur.

In the other state–called “heaven”–you are completely selfless, focusing on something that is far more important than anything that ever happened on Earth. You are in the direct presence of a Being that is the fulfillment of every spiritual, philosophical, rational, benevolent, logical, creative, poetic, and romantic yearning that humans have ever had, in their greatest moments. You are filled with an infinite amount of awe, adoration, joy, gratitude, and love at the wonderful system that let this outcome occur.

In which state do you want to exist, forever? The choice is yours.

Mario Rizzo’s Ludwig Lachmann Impression

There’s some other stuff about Israel Kirzner in here you might find interesting, but in yet another contribution, the wry von Pepe points us to 45:00 in this video:

Minimum Wage Analysis: Killing Econ 101 Via the Magic of Econometrics

I tried working my way through the Dube, Lester, and Reich (2010) paper that I think is a good representative of the “latest research” that allegedly overturns the old consensus. Now that I am pretty sure I know what happened, I have to say that if these results are allowed to guide the debate, then something really wrong is going on here.

First, let’s make sure we understand the context. Here’s their abstract:

Abstract—We use policy discontinuities at state borders to identify the

effects of minimum wages on earnings and employment in restaurants

and other low-wage sectors. Our approach generalizes the case study

method by considering all local differences in minimum wage policies

between 1990 and 2006. We compare all contiguous county-pairs in the

United States that straddle a state border and find no adverse employment

effects. We show that traditional approaches that do not account for local

economic conditions tend to produce spurious negative effects due to spatial heterogeneities in employment trends that are unrelated to minimum

wage policies. Our findings are robust to allowing for long-term effects of

minimum wage changes. [Bold added.]

That part I put in bold is crucial. When Dube, Lester, and Reich look at contiguous county-pairs that straddle a state line (and hence can have different minimum wage laws applicable to them), they too find that a “naive” regression will show that minimum wage hikes will retard the growth in unskilled employment.

However, they “correct” this result by putting in an additional explanatory variable that picks up the effect of the “state-specific trend” in employment. Once you do that, all of a sudden the point estimate of employment turns slightly positive, or at least is close to zero (depending on the specification). Now these authors don’t ever really spell it out in plain English, so let me quote from the John Schmitt CEPR literature review that Krugman liked so much. The CEPR paper says what Dube, Lester, and Reich did, and how their findings (allegedly) turned the original, anti-minimum-wage findings on their head:

Dube, Lester, and Reich’s study also identified an important flaw in much of the earlier minimumwage research based on the analysis of state-level employment patterns. The three economists

demonstrated that overall employment trends vary substantially across region, with overall

employment generally growing rapidly in parts of the country where minimum wages are low (the

South, for example) and growing more slowly in parts of the country where minimum wages tend to

be higher (the Northeast, for example). Since no researchers (even the harshest critics of the

minimum wage) believe that the minimum wage levels prevailing in the United States have had any

impact on the overall level of employment, failure to control for these underlying differences in

regional employment trends, Dube, Lester, and Reich argued, can bias statistical analyses of the

minimum wage. Standard statistical analyses that do not control for this “spatial correlation” in the

minimum wage will attribute the better employment performance in low minimum-wage states to

the lower minimum wage, rather than to whatever the real cause is that is driving the faster overall

job growth in these states (good weather, for example). Dube, Lester, and Reich use a dataset of

restaurant employment in all counties (for which they have continuous data from 1990 through

2006), not just those that lie along state borders and are able to closely match earlier research that

finds job losses associated with the minimum wage. But, once they control for region of the country,

these same earlier statistical techniques show no employment losses. They conclude: “The large

negative elasticities in the traditional specification are generated primarily by regional and local

differences in employment trends that are unrelated to minimum wage policies.”

This, I submit, is crazy talk, assuming I correctly understood what Dube, Lester, and Reich actually did in their study. Here’s my list objections:

#1)==> We are already supposed to be comparing apples to apples, by focusing on contiguous county-pairs across state lines, right? That’s why we did it this way. Yes, if the minimum wage laws all happened to be raised in an area that had a bunch of oranges to be picked, and then there was a bad harvest every time the minimum happened to get increased, then you could get a spurious negative result. But if you’re looking at contiguous county-pairs, then this shouldn’t happen. If there’s a bad orange crop in one county, then there should be a bad orange crop in the next county over (which happens to be in an adjacent state). To find the pairwise negative effect on employment that the old literature documented quite clearly, but then to correct for “state-wide” employment trends due to good weather, is crazy. You are overcorrecting.

#2)==> What Dube, Lester, and Reich are really saying here, is that maybe for some reason minimum wage hikes happen to be concentrated in regions that have lower than average employment growth. Hence, just because we find that teenage employment grows more slowly in regions with higher minimum wages, doesn’t mean we can blame it on the relatively higher minimum wage. But hang on a second. Minimum wage hikes aren’t randomly distributed around the country, such that we might happen to get an outcome where they tend to be concentrated in slow-growth regions. On the contrary, minimum wage hikes are implemented by “progressive” legislatures, who also (given my economic worldview) implement other laws that retard adult employment growth.

For example, suppose that if a state legislature jacks up the minimum wage, then it is also likely to pass “pro-labor” stuff like laws giving unions more organizing power, laws allowing unfairly terminated employees to receive years of back pay, and laws granting extra perks for maternity leave. Now, these last three items I listed: Would they reduce the employers’ incentives to hire teenagers or adults, more? On the margin, they would make it costlier to hire adults, because if penalties are expressed in years of back pay, or have to do with paid leave, or strengthen unions who traditionally are going to organize adults…You get the picture. Adults make more than teenagers, and so these rules will penalize adult employment more than teenage employment.

Thus, if my model here is correct, it would produce the pattern we actually see: Looking narrowly at minimum wage laws, they seem to retard teenage employment. But then when you ask if states with high minimum wage laws have a bigger slowdown in teen employment versus adult employment, the signal becomes much weaker. It looks like, by dumb luck, for some reason all the minimum wage hikes happen in states that also have slower-than-average employment growth among adults. And hey maybe this is due to weather, even though the weather doesn’t seem to be slowing the adult or teenage employment growth in the next county, which is in a right-to-work state with no minimum wage law.

Recent Comments