Two Views of R&R

[UPDATE below. Make sure you read that if you are just now stumbling upon this post.]

Man, Reinhart and Rogoff are getting hammered by the Keynesians lately. First of all, you’ve got commentators (here’s but one example of many) who are making it sound like all the “austerity” the last 3 years was due to an Excel mistake. This is simply ridiculous, as the R&R headline number only changes “a few tenths of a percent” when you correct the spreadsheet formula.

Although (to his credit) Krugman didn’t lead his readers to believe all of R&R’s results hinged on that Excel mistake, he too has been just blasting them. In this post on “Knaves” and “Fools” Krugman says, “And so you have the spectacle of…powerful officials instantly canonizing research papers that turn out to be garbage in, garbage out”, a clear reference to R&R. And let’s not forget this post where Krugman summed up the lessons of the R&R fiasco:

Notice, however, that the problem with the original [R&R paper] wasn’t that it failed to convey the nuances. The problem was that it was just plain wrong — wrong about America after the war, wrong about what a debt-growth correlation means. (It turns out that there was other wrongness too, but that was enough).

So the moral of the story should not be, “Don’t take strong positions”. It should instead be “Don’t take a strong position that some people want to hear if the position isn’t supported by theory and evidence”. Or maybe, even more briefly, “Don’t pander”.

And the trouble with where I think [Tyler] Cowen, at least, is going is the apparent suggestion that everyone who develops a prominent public profile in economics has to do it by pandering. No, they don’t — and specifically, I don’t think that’s what I do. I’ve taken very strong positions over the years; I’ve been wrong on some occasions; but I can’t think of any cases where I took a stronger position than my actual beliefs warranted.

So you see, it’s not just that these researchers were wrong, but that they were consciously pandering to politicians, telling them what they wanted to hear in their quest to hurt the underprivileged and reward the fat cats, when R&R knew that they were taking a stronger position than their actual beliefs warranted. Man, what horrible people!

In the interest of evenhandedness, I guess we should try to find the views of someone else to counterbalance Krugman’s strong accusations. Now to be fair, we can’t just quote from some adjunct professor at Hillsdale College. Let’s get, say, a Nobel laureate, and one who has read the entire literature on financial crises and macroeconomic policies to get us out of a depression–this is the kind of guy (or gal) we need, to give a balanced view.

Oh, I’ve got an example of just such a person, who wrote in July 2010:

Regular readers will know that I’m a huge admirer of Ken’s work, both theoretical and empirical. Obstfeld and Rogoff is the definitive work on New Keynesian open-economy macro; Reinhart and Rogoff the definitive empirical history of financial crises and their aftermath. It was largely thanks to my study of Obstfeld-Rogoff that I realized, from the get-go, that many of the arguments we were hearing about how modern macro had proved Keynesianism wrong were just ignorant; it was largely thanks to my reading of Reinhart-Rogoff that I realized, early in the game, that this was going to be a prolonged slump rather than a V-shaped recovery.

I’m reminded of Truman’s request for a one-armed economist. (HT2 Scott Sumner and James Hamilton)

UPDATE: I had not clicked through the link of Krugman’s July 2010 quote. (You can choose whether to believe this or not, but yesterday the NYT wasn’t letting me read his stuff because it said I had exceeded my monthly limit, so I didn’t think it would let me. But, for some reason today–still April–it’s letting me.) I was just relying on the quotes from the other blog posts on this.

The quote is accurate, but later in the same post Krugman says:

Unfortunately, the Reinhart-Rogoff paper now being cited all over the place – the one that suggests that there’s a critical level of government debt, at around 90 percent of GDP — doesn’t follow that strategy. All it does is look at a correlation between debt levels and growth. And since debt levels are not sharp extreme events, there’s no good reason to believe that they’re identifying a causal relationship. In fact, the case they highlight – the United States – practically screams spurious correlation: the years of high debt were also the years immediately following WWII, when the big thing happening in the economy was postwar demobilization, which naturally implied slower growth: Rosie the Riveter was going back to being a housewife.

It’s just not up to the standard of the other work. And yet Ken is leaning hard on that paper to justify his pro-austerity position.

So, had I realized that upfront, I wouldn’t have made this post. I would take it down now, except that seems Orwellian.

Ariel Rubinstein Has Amazed Me

At NYU my “field” was Game Theory, because I figured, if we’re going to formally model economic actions, then let’s get nuts. I have elsewhere criticized the big guns of game theory when they try to talk to the layperson.

So, when Tyler Cowen linked Ariel Rubinstein’s article titled, “How Game Theory will solve the problems of the Euro bloc and stop Iranian nukes,” I was getting ready to knock it out of the park. (Here’s an ungated copy of it.)

If you understand where I was coming from, then just click that link and be amazed. Read the whole thing, the end is the best part.

Heads Krugman Wins, Tails Austerians Lose

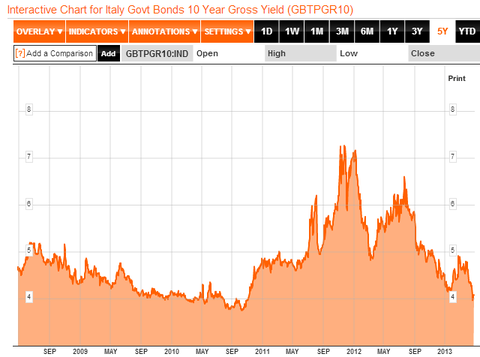

Man I am just really down lately, because the great experiment in European austerity has proven to be a disaster for “my side” of the debate. You had all these austerians predicting that the way to reassure bond markets and get yields down on fiscally suspect European nations was to make bold promises about reform. But it’s not like this “unprecedented experiment in austerity” produced something that could be described as “The Italian Miracle,” right? It’s not like Krugman would write a blog post like this:

Italy is a mess. Yes, it has a prime minster, finally; but the chances of serious economic reform are minimal, the willingness to persist in ever-harsher austerity — which the Rehns of this world tell us is essential — is evaporating. It’s all bad. But a funny thing is happening:

What’s going on here? I think that we’re seeing strong evidence for the De Grauwe view that soaring rates in the European periphery had relatively little to do with solvency concerns, and were instead a case of market panic made possible by the fact that countries that joined the euro no longer had a lender of last resort, and were subject to potential liquidity crises.

What’s happened now is that the ECB sounds increasingly willing to act as the necessary lender, and that in general the softening of austerity rhetoric makes it seem less likely that Italy will be forced into default by sheer shortage of cash. Hence, falling yields and much-reduced pressure.

So here’s how you deal with data if you’re Paul Krugman:

(A) Describe what Europe is doing as the dream plan of right-wingers, even though I can’t think of any Austrian or Chicago School guy saying that raising tax rates was a good idea for Europe.

(B) Find any example of bad economic news in Europe, and blame it on “unprecedented austerity.”

(C) Find any example of good economic news in Europe–even falling bond yields, which is exactly what the politicians claimed would happen if they implemented their “austerity”–and attribute it to the ECB doing just enough to offset the horrible fiscal policy.

(D) Then, just for kicks, claim that only a liar or a fool could possibly ignore the mountains of empirical evidence that the Keynesians have been totally vindicated by events in Europe.

Just the Facts, Ma’am: “Testing” Keynesian Theory

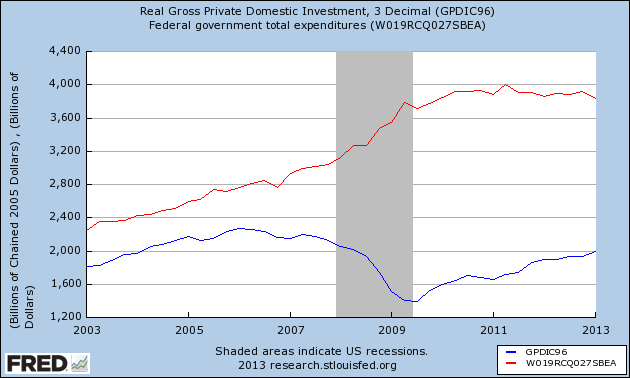

I realized that I was being too fair to “Lord Keynes” in the last post, since total GDP statistics include government expenditures. To really test whether the Obama stimulus episode seems more consistent with the Keynesian versus the Austrian story, let’s look at what happened to gross private investment (I couldn’t find any FRED series for total private GDP) when the Obama stimulus kicked in, in early 2009. Here ya go:

Again, this doesn’t prove a darned thing. But remember what Lord Keynes had said to me: “If stimulus is counterproductive, then why didn’t real output plunge even further when the stimulus was implemented?”

So my point here is that if you are a Keynesian and think the data are overwhelmingly on your side, I think you need to take a second look. There is a reason a lot of us still cling to the notion that giving politicians control over resources is hardly the path to prosperity, when the economy is already reeling.

Believing Is Seeing, Part II

“Lord Keynes” provided the most beautiful confirmation possible in the comments of my recent post. Recall that I had teased a guy for simply assuming the Keynesian theory was correct, when interpreting the economic statistics. Lord Keynes upbraided me:

As opposed to your last post, where the data strongly confirms the Keynesian story, but not yours?

If stimulus is counterproductive, then why didn’t real output plunge even further when the stimulus was implemented?

Here’s the chart of total federal expenditures vs. real GDP:

So, the data did exactly what Lord Keynes denied had happened. Yet he literally can’t see this, because he is so sure that extra government spending, other things equal, will boost a depressed economy. He’ll look at that chart and “see” that real GDP was poised to collapse even further, but finally bottomed out (after a lag) because of the Obama stimulus in early 2009.

Also apropos, let’s consider the counterfactuals: The Keynesian economists with their names on the White House analysis of the stimulus package, infamously predicted that the economy without stimulus would have a lower unemployment rate, than what the economy actually ended up getting with stimulus. There could not be a better example of exactly what Lord Keynes had demanded. The economy looked like it was on trajectory A, they implemented the stimulus, and all of a sudden “oh shoot, the economy was worse than we realized.”

(Yes yes, some Keynesians said it wouldn’t be enough. Just like some Austrians and fellow travelers [like Vijay Boyapati and Mish] said deleveraging would lead to tame CPI increases, if not outright price deflation. Yet I don’t see Lord Keynes or Krugman pleading for nuance when discussing the predictions of “the austerian camp” regarding the economy in the last four years.)

Jesus Attempts to Explain Why God Allows Evil

I was going to read my son another chapter from the second Harry Potter book, but he requested a story from “the Bible…your Bible.” (By which he meant, not the children’s animated book of Bible stories in his room.) So I flipped through and read him this, from Matthew 13: 24-30:

24 Another parable He put forth to them, saying: “The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seed in his field; 25 but while men slept, his enemy came and sowed tares among the wheat and went his way. 26 But when the grain had sprouted and produced a crop, then the tares also appeared. 27 So the servants of the owner came and said to him, ‘Sir, did you not sow good seed in your field? How then does it have tares?’ 28 He said to them, ‘An enemy has done this.’ The servants said to him, ‘Do you want us then to go and gather them up?’ 29 But he said, ‘No, lest while you gather up the tares you also uproot the wheat with them. 30 Let both grow together until the harvest, and at the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, “First gather together the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them, but gather the wheat into my barn.”’”

Look, the problem of the existence of evil is a problem. But atheists drop that like it’s a conversation ender, when in fact theologians have grappled with it all along. Indeed, Jesus Himself tries to explain it to the layperson with the above story.

My son wasn’t satisfied with the above, so I tried explaining that there couldn’t be superheroes if there were no bad guys. For example, there could be a guy “Superman” who could fly and was really strong, etc., but without any villains we wouldn’t think he was great.

In the comments last week, I pointed out that great literature always has villains or at least antagonists who present conflict for the protagonist. For some reason, people expect God–the author of history itself–to not obey an obvious rule of human creativity.

Believing Is Seeing

Presumed “wonk” Neil Irwin writes:

The [latest GDP] report details this stuck-in-neutral economy. It’s not without bright spots, but there aren’t enough of them, and they aren’t bright enough to make up for the forces dragging the recovery, most significantly a drop in government spending.

Indeed, the biggest culprit in the weak report was the government sector, which fell at a 4.1 percent rate, after a 7 percent pace of decline in the fourth quarter. The fall was universal — at the federal, state and local levels. The U.S. government is in pullback mode, and whatever one thinks about reducing the size government in the long run, for now it is unequivocally the villain in slowing growth. If there’d been no change in government spending over the last six months, GDP growth would have averaged a respectable 2.55 percent, not the current soft 1.45 percent. [Bold added.]

Why yes, Mr. Irwin, I agree: If you simply assume without even realizing it that the Keynesians are right, and that their opponents are wrong, then the Keynesians will be vindicated “unequivocally” by the data.

Why Economists Will Soon Be Lynched

I am going to accelerate my transition into stand-up comedy, because the public is going to turn on economists very, very soon. Look at this:

1) Krugman argues that severe US fiscal austerity explains our dismal economic growth.

2) I say no, there hasn’t been fiscal austerity. In fact, we have record-high spending, and that explains our dismal economic growth.

3) Mike Konczal says the authorities have done exactly what the market monetarists wanted: The federal government has engaged in severe fiscal austerity, while the Fed has aggressively upped its purchases. The latest GDP numbers show what an abysmal failure this has been. The Keynesians were right, after all: We need budget deficits to get out of this mess.

4) Scott Sumner says no, we haven’t gotten level targeting of NGDP, which is what the market monetarists want. But anyway, Scott continues, the government’s severe fiscal austerity and easing of monetary policy has led to the recent GDP numbers, which are better than last year’s. So the market monetarists were right, after all: We don’t need budget deficits to get out of this mess.

I don’t care whether you’re Austrian, Keynesian, or Sumnerian: The above is messed up. If Joe Schmoe tried to follow the economic debate on the blogosphere, he would be very upset, as you can understand, and rightly so.

Recent Comments