The Two Good Things About Christians…

…are that they publicly acknowledge that they are awful, but that there is a perfect role model to serve as a perpetual source of hope and encouragement.

The older I get, becoming wiser and seeing firsthand the nature of men and women, the more I think Christianity is the diagnosis and prescription. Other worldviews lack something essential.

For example, there are secular humanists who think humanity is basically good, with a few bad apples. Just tweak the social institutions a bit (and that “solution” is the same, for a Marxist or an atheist anarcho-capitalist), and the natural goodness of humanity will come shining through. Yet I don’t think that’s accurate. For just a quick rebuttal, I can point out: Even on its own terms, this worldview shows that humans will choose to engage in monstrous cruelty if the circumstances are right. And it’s weird to say our “natural state” is one of benevolence, when we have yet to find the “right society” to draw it out of us.

On the other hand, there are also atheists/agnostics walking around who are absolutely disgusted with humanity. Think of George Carlin in the parts of his routine where he becomes downright misanthropic. That also strikes me wrong. Every act of kindness, every work of art, shows the potential of humanity.

As in other areas, when it comes to the question of the fundamental nature of humans, I think the Christian view is more accurate and “pragmatic” than the other leading contenders. Left to their own devices, people are evil, self-destructive wretches, but they have a divine spark within them. There is hope for humanity, but their salvation won’t come merely from “trying harder.”

Murphy Sings “Mack the Knife” at Puglia’s in Little Italy

Just for bookkeeping I’m hitting the “karaoke” tag on this post, but actually this was the real deal. This guy Jorge Buccio is the 7-days-a-week entertainment for Puglia’s. He was one of the attendees on the recent financial seminar on the Caribbean cruise, and told me to let him know when I’d next be in NYC.

Potpourri

==> Not sure if I even mentioned it here, because the main event sold out…but anyway I will be at the “Anarchy in the NYC” event this Saturday. Afterward there is a karaoke party hosted by Tatiana Moroz, but you need a ticket to get in. (I am now calling myself a professional singer for this very reason. It’s a technicality, I grant you.)

==> I am sure some would draw parallels to people warning of (price) inflation, and the struggling climate scientists. I am sure Paul Krugman will be coming down hard on the scientists and their 13 years of bad model predictions…

==> Tom Woods takes on the Greenbackers’ “fake quote industry.”

==> Somehow Max Raskin went from the quirky kid at Mises U to the dashing young man all over Bloomberg.

==> Daniel Sanchez gives a tax day talk at the Mises Institute.

==> A neat tribute to Jonathan Winters from Robin Williams (HT2 Doug French).

==> As someone who does a lot of work involving Excel tables, this story horrifies me. You can choose not to believe me, but I would feel bad if this happened to Krugman. I mean, sure I go back and check for just this type of thing–make sure I didn’t inadvertently copy the wrong formula, try to get the same number by a different order of operations, etc.–but ultimately it’s tough to guard against something like this. You can say, “What about peer review?!” but in that case, you’ve never refereed a paper…

==> Speaking of Krugman: I guess it’s not a huge deal in the grand scheme of things, but in his hit piece on Bitcoin, we have yet another Kontradiction. Early in the piece Krugman remarks on the “strangeness” (his word) of Bitcoin because they “derive their value, if any, purely from self-fulfilling prophecy, the belief that other people will accept them as payment.” Then he concludes the article by saying:

Goldbugs and bitbugs alike seem to long for a pristine monetary standard, untouched by human frailty. But that’s an impossible dream. Money is, as Paul Samuelson once declared, a “social contrivance,” not something that stands outside society. Even when people relied on gold and silver coins, what made those coins useful wasn’t the precious metals they contained, it was the expectation that other people would accept them as payment.”

So it’s kind of a weird article. Krugman wants to mock the Randian libertarian types who like Bitcoin, and early on he says it’s not like gold because it’s utterly dependent on its role as a medium of exchange, and then he concludes by saying the people who like Bitcoin need to read Samuelson, who explained that money is ultimately valued because it is a medium of exchange.

Again, not a contradiction per se, just a Kontradiction. Sort of like, “It actually makes sense to like Bitcoin, but the people who like it right now are doing so for the wrong reason.”

Krugman Gloating on Gold

This really makes no sense. As everybody knows, gold just had the biggest one-day drop in three decades. Here’s Krugman’s reaction:

So, the slide in gold has turned into a rout. As Joe Weisenthal says, this should be seen as really good news, because it offers strong evidence that the goldbug/inflationista view of the world — which says that we need to stop all efforts at monetary and fiscal stimulus lest we turn into Weimar — is, in fact, all wrong.

…

Maybe, just maybe, the gold crash will finally bring intellectual capitulation. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

OK how would an inflationista explain the movements in the price of gold? He’d say it was connected with Bernanke’s wild money printing, right? So what would you expect the price of gold to do, if that theory were right?

Well, when the Fed announced a major new initiative, like QE3, you’d expect gold to shoot up. And then when the minutes came out from a Fed meeting saying they had discussed stopping asset purchases this year, you’d expect the price of gold to tumble.

And that’s exactly what happened, as even Bloomberg framed it: “On April 12, gold slumped into a bear market on concern that Cyprus may sell bullion holdings to cover a bailout, and the Federal Reserve signaled that that U.S. monetary stimulus may be scaled back this year.”

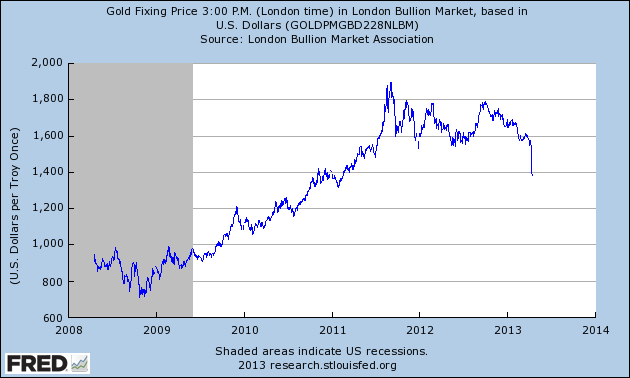

Here’s the price of gold over the last 5 years:

So even with the recent drop, it’s still up about 75% from when the Fed really kicked in with quantitative easing. You can see it zoomed up around September 2012, which was when QE3 was announced. I’m getting ready for a trip, but you guys can check and see if the timing of QE2 works also.

In contrast, what was Krugman’s theory about gold prices? Well for the first few years of the crisis, he just said ‘volatility, who the heck knows.’ (That’s a paraphrase, not an exact quote, but that’s really what he said.) Then, he blamed it on Glenn Beck (really). Finally, he was relieved when somebody suggested it was due to very low real interest rates, because then Krugman could finally give a wise, elegant model to explain why the goldbugs were confused (focusing on the Fed’s asset purchases as the trigger, instead of the falling real interest rates).

Now since Krugman congratulates himself for his willingness to admit when his model is wrong, somebody should let him know that rates across the entire yield curve slightly fell over the recent drop in gold. (Same for real yields.) This goes in the wrong direction, according to Krugman’s model. In other words, falling interest rates should mean gold prices go up. (NOTE: That link to the Treasury yield curve data isn’t time-stamped, so it will be obsolete soon after this post runs.)

So there you have it: The qualitative movements in the gold price generally fit the “goldbug, crazy Bernanke” story, including the fact that gold is still way up from its level pre-crisis. In contrast, Krugman’s own model of gold prices doesn’t even go in the right direction for the recent crash.

Look, no simple model is going to explain every zig and zag of the price of gold, and obviously I don’t endorse a long-term rational expectations approach to commodity prices; of course there are bubbles and busts possible in any asset class. (I’m also aware of speculation about rigging the market, but I just don’t know enough to comment on these claims.)

My simple point is, once again, Krugman is running a victory lap for data that generally match his opponents’ worldview, but are completely at odds with his own. Isn’t that weird?

Potpourri

==> Whether North Korean officials actually said this, or whether it is US propaganda to get Americans mad, either way it’s hilarious: They allegedly called the US mainland a “boiled pumpkin.” Who can drop bombs after such a funny insult?

==> Robert Higgs looks around at today’s libertarians, and he’s none too impressed. His op ed reminded me of Alec Baldwin in Glenngarry Glenn Ross (naughty language).

==> I did an interview on financial topics with a guy named Mo, but alas, he didn’t call me a wiseguy.

==> All joking aside for the moment, this abortionist grand jury stuff is pretty shocking. I can understand why people are outraged that it isn’t getting more media coverage.

==> David R. Henderson points out that “crying wolf” warnings from government are counterproductive. I thought the same thing when I was growing up, because there was a definite point at which I noticed the disclaimers on TV commercials got ubiquitous. All of a sudden, every product had an announcer speed-reading a list of awful things that might conceivably happen if you took Product X. At first comedians made fun of it, but after a while you got desensitized, such that nobody even listened to the warnings anymore. Hey, everything causes cancer. You shouldn’t take anything if you’re pregnant or have a heart condition. Etc.

==> Some of my favorite bloggers have been having a war over interest rate theory. As this was the subject of my dissertation, you’d think I’d be hip-deep in it by now. (In the sense that I would be commenting, not that any of them would acknowledge my existence.) I understand quite well what Krugman and DeLong are saying, but unfortunately I am not really clear on the Cowen/Andolfatto/Williamson position (and in fact I wonder if the latter three even have the same position, since I think Williamson embraces fiscal policy while the other two say their diagnosis leads to a different prescription).

But none of that matters. The important thing is the following, hilarious exchange:

First, DeLong took Cowen out to the woodshed for (allegedly) failing to make a distinction that Knut Wicksell made in 1890. Then DeLong ends with, “This is not rocket science. This is basic Geldzins und Guterpreis…”

Then, Cowen shoots back with a long post containing this quick line amidst all of the boring econ chatter: “Brad also chides me for neglecting “basic Geldzins und Guterpreis”, but speaking of basics he neglects the umlaut and also the plural on “price”, so it should be “Güterpreise“, the German-language title then being translated somewhat inexactly into “Interest and Prices.””

DA-YUM! That may not sound snippy to you outsiders, but that was the academic equivalent of Tyler saying, “Hey Brad, I got your Knut right here.”

Bitcoin From an Austro-Libertarian Perspective, Part I

[NOTE: If my memory is right, two or three years ago Chris Brunner encouraged me to write an article on Bitcoin since it was getting popular. I started an article, intending Chris and Silas Barta to be co-authors, since both of them had expertise in certain areas (Chris from a network / commercial point of view, Silas from an individual miner’s perspective) and I really needed to understand the mechanics of Bitcoin before I could pontificate on its economic and political ramifications. I did a bunch of research and had a few phone calls with Chris, and started an article that began with an elaborate analogy to explain the nuts and bolts of Bitcoin without using any scary mathematical or cryptography terms. Silas Barta worked with me on refining the analogy, but then the article stayed buried in my hard drive until a few days ago. With the recent, renewed interest in Bitcoin, I hoisted the article out of its dusty folder, and Silas and I finished just the first section. This is what I am now running as Part I in a series on Bitcoin. Silas is currently writing up the main draft of Part II, which will deal with mining. Eventually we will get around to discussing the economics–does Bitcoin violate the regression theorem? is it a fiat currency? etc.–and the implications for liberty activists.—-RPM]

by Robert P. Murphy and Silas Barta

One of the hottest topics lately in Austro-libertarian circles is Bitcoin, which its official website describes as a “peer-to-peer virtual currency.” Supporters claim that Bitcoin is the ultimate free-market money of the computer age, because its scarcity is mathematically guaranteed and is virtually impervious to government counterfeiting efforts. Detractors argue that it is a fad, and that only a physical commodity can last as a true money.

In the present article we’ll try to explain what Bitcoin is, and how it works. The topic is tricky because Bitcoin’s implementation relies on distributed computational procedures (carried out by a network of different machines) and encryption. So in this first article of a series, we will simply try to give an analogy for the big-picture understanding of how Bitcoin actually works, where we hope to strike a balance between accuracy and comprehension for those not familiar with “mathematical trapdoor functions” and “public/private key protocols.” In future articles, we’ll talk more about its implications, and how it relates to commodity monies like gold in an Austro-libertarian framework.

How Bitcoin Works: An Analogy

The first thing we want to stress is that—contrary to the impression one might have gotten—all of Bitcoin’s “bookkeeping” is done in full public view. Far from being encrypted, every Bitcoin transaction is out in the open, subject to independent auditing by anyone who downloads the software. In fact, that’s the very strength of Bitcoin, and why its proponents say that it relies on no central authority: Precisely because no single organization is “in charge” of Bitcoin, it will be extremely difficult to stamp it out of existence if Bitcoin should ever become a commonly accepted currency. Friedrich Hayek talked of privately-issued fiat currencies, but his vision still involved management of each (competing) currency by a particular issuer. In contrast, no single group manages Bitcoin; this is the sense in which it is “decentralized.” (However, it’s true that a commodity money like gold is also decentralized in the same sense.)

To gain a full appreciation of how Bitcoin works, it’s necessary to go into the mechanics of public key cryptography, which one of us has done (in a very accessible way) here and here. In the present article, we’ll keep it as painless as possible by using an analogy, which we hope will get across the essence of Bitcoin without losing too many readers in the technicalities.

Imagine a community where the people don’t use tangible money: there are no gold coins, but not any green dollar bills, either. Instead, the money in this community is based on the 21 million integers running from 1, 2, 3, …, 20,999,999, and finally up through 21,000,000. At any given time, one person “owns” the number 8, while somebody else “owns” the number 34,323, and so on. To speak this way doesn’t mean that people have to pay for the privilege of engaging in arithmetic with these numbers. (In other words, this isn’t some weird thought experiment about Intellectual Property taken to the extreme.) Rather, we simply mean that when commercial transactions do occur, the medium of exchange is the community’s notion of “ownership” or “assignment” of these 21 million integers to specific individuals.

For example, suppose Bill wants to buy a car from Sally, and the price sticker on the car reads, “Two numbers.” Bill happens to be in possession of the numbers 18 and 112. So Bill trades the two numbers—18 and 112—over to Sally, and Sally gives Bill the car. The community recognizes that the title to the car has transferred from Sally to Bill, and it also recognizes that Sally is now the owner of the numbers 18 and 112.

Now we come to the really interesting part. With the car, the title was a piece of paper; when she sells the car, Sally has to sign over the title to Bill. In principle this piece of paper could be destroyed, stolen and altered, or fraudulently produced. But with the numbers, things are different; the mechanism through which Bill transfers his ownership of 18 and 112 to Sally is complex. What happens is that the community keeps track of ownership through an industry of thousands of accountants. They each keep enormous ledgers (in Excel files or giant pieces of paper if you like), with 21 million columns running across the top from left to right—one for each number.

So the columns run across the top, from 1 to 21 million. At the same time, the rows of the ledgers record every transfer of a particular number. For example, when Bill bought the car from Sally, the accountants who were in earshot the of the deal wrote down (or entered into their Excel file), “Now in possession of Sally” in the next available row, in the column for 18 and also the column for 112. In these ledgers, if we looked one row above, we would see, “Now in the possession of Bill” for these two numbers, because they were originally owned by Bill before he transferred them to Sally.

Besides documenting any transactions that happen to be in earshot, the accountants also periodically check their own ledgers against those of their neighbors. If they ever discover that their neighbors have recorded transactions for other numbers (regarding deals for which the accountant in question was not in earshot), then the accountant fills in those missing row entries in the column for that number.

Given this arrangement, at any given time there are thousands of accountants, each of whom has a virtually complete history of all 21 million numbers, from the first owner up through the present owner. The only reason the ledgers might differ from one accountant to another, is if one of them had recorded a relatively recent exchange, which had not had time to propagate (through the copying process) throughout the entire community. But any commercial transaction that is at least a few hours old (let’s say), has had time to be copied by every accountant, and so all of the ledgers in the community will have a record of the sale.

Now in this hypothetical world, if someone asks, “Who keeps track of the money?” the answer would be, “The accountants.” But if even half of the accountants and their ledgers were killed in a giant explosion, the financial system would remain intact, because all of those records were massively duplicated across the whole industry of accountants. The only things that might be lost would be sales that had occurred only an hour or two before the explosion, because these might not have had time to propagate over to the accountants who end up surviving the explosion.

Explaining the Relevance to Bitcoin, So Far

Let’s pause in our analogy to make sure the reader understands why we’ve constructed it this way. When all of the Bitcoins have been “mined”—which will happen in the year 2140—there will be 21 million of them in existence. That is a mathematically guaranteed, fixed quantity of them. (To facilitate trade, each Bitcoin can be divided into 100 million sub-components, representing up to eight decimal places. In other words, people have the technical ability to transfer ownership of 0.00000001 of one of their Bitcoins, but that is the smallest “unit” possible within the Bitcoin protocol. In this sense, there will actually be—in the year 2140 when all Bitcoins have been mined—a grand total of 2.1 quadrillion fundamental units of the currency.)

In our analogy above, we aren’t dealing with the complicated issue of “mining” Bitcoins. Instead, we are focusing on the steady-state where all of the 21 million Bitcoins have been mined, and the community functions economically just by transferring ownership of the forever-fixed quantity of these mathematical objects.

So in the real world, people transfer their ownership of a certain amount of Bitcoin to other people, in exchange for goods and services. This transfer is effected by the network of computers performing computations and thereby changing the “public key” to which the “sold” Bitcoins are assigned.

In our analogy, we captured this aspect of things by saying the accountants entered the new owner of a particular number in the next-available row in that number’s column. In the real world, the entire Bitcoin network has an entire history of each Bitcoin’s “life cycle,” from the moment it was mined, through every owner it ever had, down to the current owner. In our analogy, we captured this aspect by saying that you could look at the number 18, for example, and see its first owner in row 2, its second owner in row 3, etc. (We assume the first row is reserved for listing the integers themselves.)

Where Does Encryption Come In? The Problem of Anonymous Owners

Now in our fictitious world, there is still one glaring problem we need to address: How do the accountants verify the identity of the people who try to buy things with numbers? In our example, Bill wanted to sell 18 and 112 to Sally for her car.

Now Bill really is the owner of the numbers 18 and 112; he can afford Sally’s car, because she’s asking “Two numbers” for it. (And by the way, in this community when people quote a price in terms of “numbers” everybody knows it means “between 1 and 21 million,” because any integer outside this range is not considered legitimate money.) The accountants will verify, if asked, that Bill is the owner of those numbers; it says “Bill” in the last row which has an entry in it, under the “18” column and the “112” column in all of their ledgers.

But here’s the problem: When the nearby accountants see Bill trying to buy the car from Sally, how do they know that that human being actually IS the “Bill” listed in their ledgers? There needs to be some way that the real Bill can demonstrate to all of the accountants that he is in fact the same guy referred to in their ledgers. To prevent fraudulent spending of one’s money by an unauthorized party, this mechanism must be such that only the real Bill will be able to convince the accountants that he’s the guy.

In the real world, this is where all of the complicated public/private key encryption stuff comes in. Again, if you are feeling up to the challenge, read these more technical posts (here and here) for an explanation of the computational mechanics behind Bitcoin transfers. But for our article here, we’ll try to water it down to give the essence of what’s happening, without scary mathematical terms.

Unfortunately, at this point our story gets a little silly, which just means we haven’t been able to come up with a good analogy for this aspect of the Bitcoin process. But without further ado, suppose the following is how the people in our fictitious world deal with the problem of matching the names in the ledgers with real-world human beings:

Each time one of the numbers is transferred in a sale, the new owner has to invent a riddle that only he or she can solve. The thing is, the people in the community are clever enough to recognize the correct answer to the riddle when they hear it, but they are not nearly creative enough to discover the answer on their own.

For example, when Bill himself received the numbers 18 and 112 from his employer—Bill gets paid “two numbers” every month in salary—the accountants said to Bill:

“OK, to protect your ownership of these two numbers, invent a riddle that we will associate with them. We will embed the riddle inside the same cell in our ledger as the name “Bill,” in the columns under 18 and 112. Then, when you want to spend these two numbers, you tell us the answer to your riddle. We will only release these numbers to a new owner, if the person claiming to be “Bill” can answer the riddle. Keep in mind, Bill, that you might be on the other side of town, surrounded by accountants you have never seen before, when you want to spend these numbers. That’s why our seeing you right now, isn’t good enough. We need to put down a riddle in our ledgers, which will also be copied thousands of times as the information pertaining to this sale reverberates throughout the community, so that every accountant will eventually have “Bill” and your riddle, embedded in the correct cell in his or her ledger.”

Bill thinks for a moment and then has an ingenious riddle. He tells the accountants, “When is a door not a door?” They dutifully write down the riddle, which then gets propagated throughout the community.

A few days later, some villain tries to impersonate Bill. He wants to buy a necklace that has a price tag of “one number.” So the villain says to the accountants in earshot, “I’m Bill. I am the owner of 112, as everyone can see; these spreadsheets are public information. So I transfer my ownership of 112 to this jeweler, in exchange for the necklace.”

The accountants say, “OK Bill, just verify your identity. What is the solution to your riddle? Tell us, ‘When is a door not a door?’”

The villain thinks and thinks, but can’t come up with anything. He says, “When the door isn’t a door!” The accountants look at each other, scratch their heads, and agree, “No, that’s a dumb answer. That didn’t solve the riddle.” So they deny the sale; the villain is not given the necklace.

Now, a few weeks later, we are up to the point at which our story originally began, at the beginning of this article. The real Bill wants to buy Sally’s car for “two numbers.” He announces to the nearby accountants, “I am the owner of 18 and 112. I verify this by solving my riddle: A door is not a door when it’s ajar.”

The accountants all beam with delight! Aha! That is a good answer to the riddle. They agree this must be the real Bill, and allow the sale to go through. They write down “Sally” in the next-available rows in columns 18 and 112, and then ask Sally to give them a new riddle, to which only Sally would know the answer.

Explaining the Relevance to Bitcoin, Once Again

Even though we had to strain the story a bit—since in reality, it would be pretty easy for someone to guess the solution to Bill’s riddle—we think this is a decent analogy to how Bitcoin actually works. Without getting into the details, there is a way that the actual owner can perform an operation mathematically, which can only be reversed with possession of a specific number. This special number is the “private key.” In our story, the private key would be analogous to Bill’s mental ability to solve his own riddle, and the actual solution to the riddle would be his “signature.” In the real world, once given a “signature” that can only be generated by someone with the private key, the computers in the Bitcoin network can recognize that the owner is legitimate, but it would take thousands of years of computing power (with current technology) for an outsider to guess the private key and hence produce a “valid” signature. Even the CIA with its supercomputers thus couldn’t transfer someone else’s Bitcoins.

One final twist of realism: In the real world, people don’t need to use their actual names such as “Bill” to identify themselves as the owner of a particular Bitcoin. Instead, they can use any old identifier. This identifier is the “public key,” which all can see. In our analogy, it would be as if Bill told the accountants, “Call me ‘CoolKat’ in your ledgers.” Then, to prove that he was in fact “CoolKat,” Bill would have to answer the riddle, just as before.

The reason libertarians are so excited about this aspect, is that Bill can disguise how many numbers he possesses. He can slap the label “CoolKat” on 18 and 112, but he can throw “JamesBondFan” on his other numbers 45 and 974. So Bill owns four numbers total, but nobody else in the community—not even the accountants—would know this. As far as the records indicate, 18 and 112 are owned by “CoolKat,” while “JamesBondFan” owns 45 and 974. Nobody but Bill realizes that these point to the same human being.

This wraps up our present post. We hope we’ve given an intuitive, yet accurate, explanation of the basic mechanics of Bitcoin. In future posts we will address Bitcoin’s relevance to Austro-libertarians.

Not a Shred of Evidence for God?

One of the things that amuses me in “science vs. religion” debates (in quotation marks because I think that’s a false dichotomy, like have a debate between Superman and pizza) is the overblown rhetoric coming from the supposedly objective, rational, empirical side. (I’m sure the theists do it too, but they’re supposed to be the emotional hotheads, so it’s not as ironic.)

For example, in discussing evolutionary biology and Intelligent Design, you will hear things like, “the Darwinian theory of common descent is as well-established as the law of gravity,” which is insane.

Another typical example goes like this: “I do not reject the existence of God out of hand, and in that weak sense I’m an agnostic, not an atheist. I can’t prove there is no God. But if he does exist, why isn’t there a shred of evidence?”

On this blog, I’ve brought up things like the fine-tuning argument, the unexpected beauty of mathematics, my own personal experiences (which I realize shouldn’t convince any of you guys much, but they were certainly evidence to me), as well as the whole legacy of a guy named Jesus thing. But how about these two recent items instead?

==> An account from a neurosurgeon who had an out-of-body experience while in a coma. An excerpt:

As a neurosurgeon, I did not believe in the phenomenon of near-death experiences. I grew up in a scientific world, the son of a neurosurgeon…I understand what happens to the brain when people are near death, and I had always believed there were good scientific explanations for the heavenly out-of-body journeys described by those who narrowly escaped death.

Although I considered myself a faithful Christian, I was so more in name than in actual belief. I didn’t begrudge those who wanted to believe that Jesus was more than simply a good man who had suffered at the hands of the world. I sympathized deeply with those who wanted to believe that there was a God somewhere out there who loved us unconditionally. In fact, I envied such people the security that those beliefs no doubt provided. But as a scientist, I simply knew better than to believe them myself.

In the fall of 2008, however, after seven days in a coma during which the human part of my brain, the neocortex, was inactivated, I experienced something so profound that it gave me a scientific reason to believe in consciousness after death.

…

I’m not the first person to have discovered evidence that consciousness exists beyond the body. Brief, wonderful glimpses of this realm are as old as human history. But as far as I know, no one before me has ever traveled to this dimension (a) while their cortex was completely shut down, and (b) while their body was under minute medical observation, as mine was for the full seven days of my coma. [Bold added.]

===> But that’s just another anecdote, from a self-professed believer, right? So how about this NPR interview with the scientist who studied many such reports?

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Terry Gross. What happens when we die – wouldn’t we all like to know? We can’t bring people back from the dead to tell us but in some cases, we almost can. Resuscitation medicine is now sometimes capable of reviving people after their hearts have stopped beating and their brains have flat lined. And some of those people report being conscious during the period after their heart stopped, before they’ve been restarted.

These experiences are popularly known as near-death experiences. But my guest, Dr. Sam Parnia, prefers to call them after-death experiences. He’s a critical-care doctor who is the director of resuscitation research at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine. He’s conducting research into optimal cardiac arrest care, and into the experiences some cardiac arrest patients report they have brought back from the other side of death.

…

[PARNIA:] Now, what we study is not people who are near death. We study people who have objectively died. These people have been dead for tens, sometimes hours – tens of minutes and sometimes hours of time. And therefore, what we’ve understood is that the experience that these people have of going beyond the threshold of death, entering the period after death for the first few minutes, tens of minutes or hours of time, provides us with an indication of what we’re all likely to experience when we go through death.And that’s why I call these an actual death experience, because the physiology and the biology of the human brain is very well-studied, it’s very well-understood, and it’s standardized, which means that we can study it in a scientific fashion.

…

And what I find most fascinating about the experiences are the cases where people have come back and described to their physicians, with astonishing detail, of what had been going on. And they described watching things, and described hearing conversations – and recalling them incredibly accurately.GROSS: When you say what had been going on, you mean going on in the hospital room after the patient’s heart had stopped, while doctors were trying to resuscitate them?

PARNIA: Absolutely. So they may describe events that were going on while they were being resuscitated. They may describe events that were going on outside their room, family members’ conversations that were going on that were not even in the room they were in, but things that have been verified.

And although a lot of people had traditionally tended to discard these experiences – and possibly for the right reasons because we didn’t have a science to explain it. But if you look at it scientifically, there are now millions and millions of people around the world who have had these experiences, sometimes children less than 3 years old, who have had very accurate descriptions of what was going on that were similar to what adults have described. And therefore, it’s important for scientists like ourselves to bring them into the mainstream and study these objectively.

The general trend of what they describe, aside from the sensation of being very peaceful, is seeing a bright light; sometimes a very warm, welcoming, loving being that they describe as being full of compassion, that guides them through their lives. They often describe having a review of their lives, everything that they had done from early childhood to that point. And interestingly, the way they describe their review is very much like they experience, sometimes, everything that they had done. So for instance, if they had hurt somebody’s feelings, even inadvertently, without purpose, they feel the pain that they had given somebody else. And therefore, they judge themselves, in effect, and their actions. And that’s why when they come back, many of them are motivated to lead their lives in a completely different way. I remember one person who said that, I particularly wanted to make sure that I don’t fail again; and I want to make sure that I at least end up with a C, when I get back there again. [Bold added.]

I submit that there is far more objective, “scientific” evidence of an afterlife than there is of many things that atheists believe in without hesitation. And for that last part I put in bold, let’s recall what I said about such matters on this very blog, when I wrote:

Suppose for the sake of argument then when you die, there is indeed an afterlife. You are still conscious. However, you suddenly have access to all of history; you can contemplate, in one fell swoop, every event in the universe, from the moment of its creation to its destruction.

Now, from that newfound perspective–which is so far beyond our current abilities that we can barely even talk about it, let alone really imagine what it would feel like–you become acutely aware of the ramifications of people’s free choices. There are obvious things, of course, like seeing the effect of Karl Marx putting his views down on paper, when history might have unfolded very differently if he had written commercial jingles instead.

But there’s more. You realize, to your absolute horror and astonishment, how much extra misery YOU brought into the world. Even if you thought you were a “good person,” the effects of your relative slips were that much more severe. You see that when you were in a bad mood one morning, and honked on your horn unnecessarily when a lady cut you off in traffic, that set in motion a chain of events that ultimately led to a bicyclist getting paralyzed 8 minutes later.

Can we admit that that was a pretty good guess that I had? I had never heard of that from others; that was “my” idea (in quotation marks because I actually thought it was inspired at the time the notion occurred to me, and I really do mean that it “felt different” from how I come up with thoughts about overlapping generation models or Say’s Law).

Finally: I hardly expect this blog post to change anyone’s mind on the ultimate question of whether there is God or an afterlife. But can we at least stop saying, “There’s no evidence for your irrational beliefs.”? There’s a bunch of evidence, it’s just that many atheists apparently can’t even see it.

A Quick Note on the Free-Market Discussion of Say’s Law

[UPDATE in the text.]

In my last post I linked to a critique of my position on Say’s Law, and said that because the writer (“Smiling Dave”) went so far as to wonder aloud if I had even *read* Say’s Law, that it wasn’t worth my time debating him.

In the comments, long-time commenter “Major Freedom” encouraged me to point out the problem, since he (MF) thought the guy had a point. So, lest I come off as a snob, here it is. (But one quick clarification: Look at how the guy handles himself in the comments. My reluctance to engage in scholarly debate isn’t because “waaaa he hurt my feelings,” but because it is crystal clear he won’t change his mind. I stand by my original cost/benefit analysis: An additional hour of my time spent with Team Brittany would be much better for the world.)

So here’s the progression of the argument over Say’s Law, and why I thought Gene Callahan’s post was interesting.

1) People from time immemorial have blamed depressions on a “general glut,” i.e. too much production of every good and service.

2) J.B. Say made some observations about markets, out of which popped the notion that a “general glut” was actually impossible. What was possible is that some markets were producing “too much” (in a sense that economists could precisely define), but the corollary was that other markets were producing “too litte.” The way to fix that wasn’t to scale back “total output” per se, but simply to redirect resources from the “over” to the “under” lines. Flexible prices and absence of government intervention were great ways to hurry that process along.

3) Now at this point, Smiling Dave interjects that my point (2) shows that I have forgotten Austrian business cycle theory, and makes him wonder if I even read Say’s Law in the first place. (Note: Smiling Dave says he edited his original post to take out the snark, so it might not be there now. But these are claims he made in the original critique.) This is ironic, since point (2) above wasn’t original with me, it comes from Murray Rothbard’s description:

But if there can be no general overproduction short of the Garden of Eden, then why do businessmen and observers so often complain about a general glut? In one sense, a surplus of one or more commodities simply means that too little has been produced of other commodities for which they might exchange. Looked at in another way, since we know that an increased supply of any product lowers its price, then if any unsold surplus of one or more goods exists, this price should fall, thereby stimulating demand so that the full amount will be purchased. There can never be any problem of “overproduction” or “underconsumption” on the free market because prices can always fall until the markets are cleared…Those who complain about overproduction or underconsumption rarely talk in terms of price, yet these concepts are virtually meaningless if the price system is not always held in mind. The question should always be: production or sales at what price! Demand or consumption at what price! There is never any genuine unsold surplus, or “glut,” whether specific or general over the whole economy, if prices are free to fall to clear the market and eliminate the surplus.

So, if Smiling Dave is right that even my recapitulation of the “typical free market response” on Say’s Law shows my ignorance of Austrian business cycle theory, then Murray Rothbard must have missed the boat too. Again, that’s *possible*, but I’m going to go with Rothbard and myself, over Smiling Dave, on this one.

4) Gene Callahan gave a little thought experiment, that made me think in terms of present and future goods and services. (Note how “Austrian” this is…) We also needed to deal with the fact that leisure is a present consumption good. In light of these subtleties, I realized that maybe it’s a bit odd to say, “No, a general glut is impossible, there can be overproduction in some lines, but only if there is underproduction in others lines,” if it so happens that all of the overproduction is concentrated in present goods (including leisure), while the underproduction is concentrated in future goods. If you think through what that would look like, why it has the same observable features as “an economic depression.”

5) The point here isn’t to say, “Ha ha, J.B. Say was an idiot and Keynes kicks butt!! Obama Stimulus Package for the win!” No, the point (at least my point) was that the way I had always handled Say’s Law, and its place in the history of economic thought regarding the analysis of economic depressions, needed to be more nuanced. I had always thought of it exclusively in a static sense, with markets for present goods and services only. But once you introduce the time element, it’s a little trickier and makes people who talk about an excess demand for money or for “safe assets” not seem as crazy after all.

UPDATE: I should have re-read my original post more carefully before giving this summary. The type of example Gene gave isn’t really one resembling a depression, but rather is a more intuitive example of people producing “too much stuff” in the present (or recent past, if you prefer). If every human being worked 20 hours a day for the next year, and we burned off 90% of the depletable natural resources (crude oil, natural gas, etc.) on earth, there would be a definite sense in which “we produced way too much this year.”

Now the way to salvage Say’s Law–in the conventional free-market handling of it–is to say, “No, we produced too much of all of the goods and services that are conventionally for sale, and we underproduced the goods ‘present lesiure’ and ‘oil and natural gas that could have been sold in the future.'” There’s nothing objectionable to that, per se, but it’s a little funky, and in any event it redefines terms from what a lot of people mean when they say, “A general glut is possible.”

So, this really has nothing to do with diagnosing a depression, so much as it was a quirky little thing to show that the standard way free-market people dispose of the idea of a “general glut” is more nuanced than the usual exposition shows.

Recent Comments