Intro Notes on Economic Inequality

In case you are new to this stuff and don’t like all that book-learnin’, some intro thoughts. Some excerpts:

First of all, there’s a distinction between income and wealth. The top 1% of income earners aren’t necessarily the same group of people as the wealthiest 1%. For example, imagine a small hedge fund manager in his 30s who has a great year, pulling in $20 million in income, even though his net worth is only $5 million. But meanwhile there’s an heiress to a family fortune who owns $500 million worth of property, even though she only earns $1 million in reported income that year. These people would be ranked differently in percentile groups, depending on whether we’re talking income vs. wealth.

…

Another important point to keep in mind in that income and wealth are created, not distributed. People will often make claims along the lines of “the top 1% appropriated x% of the income gains over the last two decades.” That makes it sound as if there’s a fixed pie of income (or wealth), and so if a rich person makes more, it means a poor person makes less. In general that’s not true. Innovators like Steve Jobs didn’t become billionaires by stealing wealth away from everybody else; no, they created it.

…

Another crucial point is that the usual statistics about the “gains of the top 1%” hide the mobility of people within these percentage rankings. Let me give an exaggerated example just to make the point: Suppose the today’s poorest 1% suddenly earn $1 billion each next year. Furthermore, suppose everybody else earns the same amount next year, as they earned this year. In this contrived scenario, the standard statistics would show that “the top 1% absorbed 100% of the income gains in 2015, while the bottom 99% saw zero income growth.”

More Piketty Stuff

==> Piketty only regrets not jacking those trend lines up even more, because of the blockbuster March 2014 PowerPoint.

==> Scott Winship clarifies just how ambiguous the data really are, notwithstanding Krugman’s recent “denier” finger-wagging.

==> Speaking of which, in that article Krugman linked to a Kopczuk paper to bolster Krugman’s claims that everybody knows there’s little mobility among the wealthiest. Awkwardly, Kopczuk on Twitter says the paper didn’t show that, and notes the irony of Krugman calling his opponents intellectually dishonest. But it’s not like Krugman’s getting paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to stay on top of the inequality literature…

Check Your Hurricane Privilege

A lot of people were having fun with this study:

People don’t take hurricanes as seriously if they have a feminine name and the consequences are deadly, finds a new groundbreaking study.

Female-named storms have historically killed more because people neither consider them as risky nor take the same precautions, the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concludes.Researchers at the University of Illinois and Arizona State University examined six decades of hurricane death rates according to gender, spanning 1950 and 2012. Of the 47 most damaging hurricanes, the female-named hurricanes produced an average of 45 deaths compared to 23 deaths in male-named storms, or almost double the number of fatalities. (The study excluded Katrina and Audrey, outlier storms that would skew the model).

The difference in death rates between genders was even more pronounced when comparing strongly masculine names versus strongly feminine ones.

“[Our] model suggests that changing a severe hurricane’s name from Charley … to Eloise … could nearly triple its death toll,” the study says.

I didn’t read the study itself, so I’m hoping they accounted for this, but in any event: It occurs to me that the “sexism” could go the other way: When male researchers see a force of nature that is going to destroy everything in its path for no good reason…they name it after a woman.

See? That’s plenty sexist and it goes the other way!

Do “Productivity” and Lagging Wage Growth Disprove Marginal Productivity Theory?

In response to my book review of Piketty, where I claimed in my cutesy “Jetsons” example that a slow-down in capital accumulation would reduce the growth in workers’ real incomes, people have been throwing BLS charts in my face. To take an example from today, on Twitter:

@libertarianJ @PorphyConob @BobMurphyEcon "more physically productive per hour, and hence will be paid more." No

http://t.co/2mySdSfRns

— Professor Zaius (@ProfessorZaius) June 3, 2014

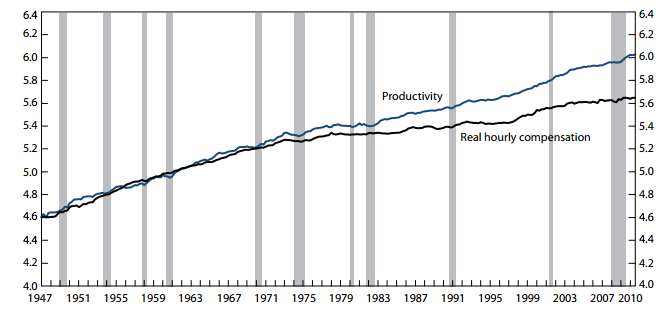

This is the paper to which he links. From that paper, here’s the money chart that supposedly blows up my claim that workers get paid more as capital accumulates:

Yikes! Everyone see the outrage? The productivity of labor has been rising nicely for decades, and yet real labor compensation hasn’t kept up. Therefore, according to my critics, I’ve got my head buried in my Econ 101 textbook and need to look out the window at the real world. Workers apparently don’t get paid more, even as accumulating capital goods make their labor hours more physically productive.

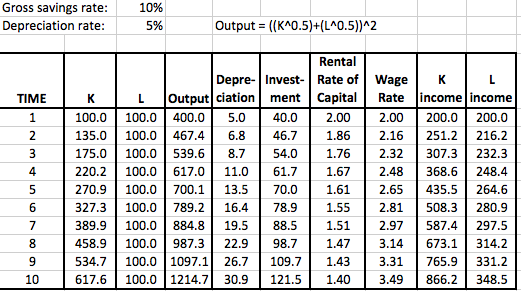

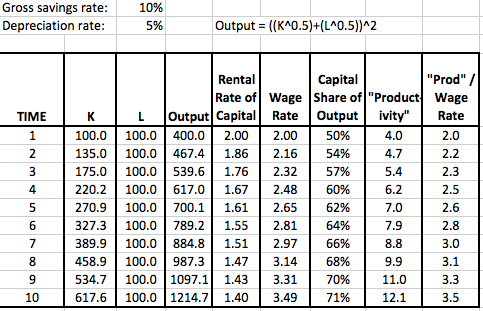

I will do a more comprehensive response elsewhere, but here I just want to post the results of a simple Excel demonstration. I used a version of the Solow growth model, but instead of the usual “Cobb-Douglas” functional form, I picked one that allows for the factors of production (i.e. capital and labor) to earn different shares of total output, depending on which one grows faster.

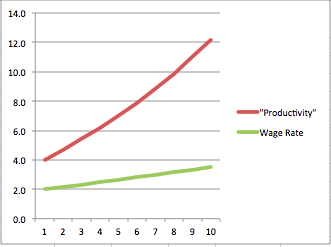

I’m not going to dwell too much here on the meaning of it all. Just note in the screenshots below that capital and labor both earn their marginal products; there is no “exploitation” going on here. And yet “productivity”–which the BLS defines as total output divided by unit of labor input–grows much faster than the real wage rate. So once you wrap your head around my example below, look again at the chart above and see if it changes your interpretation of what it means for marginal productivity theory, and my claims about Piketty.

Scott Sumner Learns the Truth About Piketty Firsthand

I just love it when I see people first read Piketty and post their reactions (on FB or blogs) to the effect of, “Wait a second… Is he really saying that? Am I missing something?” Scott Sumner has such a post; this is truly the third such post I’ve seen from a college professor in the last two weeks.

Here are some of Scott’s reactions:

I’ve started Piketty’s new book, but just finished the first chapter (intro.) Here are a few initial observations:

…

2. He says that “all the historical data” shows that real wages in Britain did poorly in the first 1/2 to 2/3rds of the 19th century. I’m no expert here, but that’s not what I was taught. I was taught (at both Wisconsin and Chicago) that the data conflicted. Some data showed what Piketty claims, and some data suggested that real wages rose, that British workers did better than peasants, and also better than people on the continent. Does anyone know whether all the data supports Piketty’s claim?3. He is rather dismissive of those he disagrees with. At Econlog I extensively discuss his mischaracterization of Simon Kuznets’ views. That’s the post to read if you are a visitor from MR and only have time for one.

…

I had read numerous reviews of the book, pro and con, before I started reading it, so I was well aware of the importance Piketty placed on the r>g relationship. When I first heard about this model it struck me as absurd. I started reading the book, thinking Piketty would provide some sort of persuasive explanation for the model. After all, the book is been very well reviewed, for the most part. And yet right after these two paragraphs, here’s what I found:When the rate of return on capital significantly exceeds the growth rate of the economy (as it did through much of history until the nineteenth century and as is likely to be the case again in the twenty-first century), then it logically follows that inherited wealth grows faster than output and income.

This is even more absurd than I expected. It does not logically follow that inherited wealth grows faster than output and income. It just doesn’t. It’s wrong. I really don’t know what else to say, other than it’s wrong. At some level the Piketty probably understands his claim was incorrect, as he contradicts himself in the very next sentence…

…However I do think it’s a big problem for Piketty’s book. If the book is a model plus data plus policy advocacy, then in my view he’s lost one third of the book in the opening chapter. In later posts I’ll let you know whether he collects the data that is most relevant to the issue of economic inequality, and whether he has good arguments for or against the standard remedy of a progressive consumption tax, with zero taxes on capital.

PS. After writing this I noticed a book edited by Joel Mokyr has a article by Deirdre McCloskey that claims British real incomes rose by two and a half times between 1780 and 1860, but that’s an average, and doesn’t account for changes in income distribution. Another article by Clark Nardinelli suggests that real incomes doubled between 1760 and 1860 and the share of income going to the bottom 65% fell from 29% to 25%. But even that suggest a substantial gain for average people. So I’m not sure that “all the historical data” shows what Piketty claims it shows.

For what it’s worth, in the comments of Scott’s post Mark Sadowski claims:

If anything, there’s been an epic duel (well, “epic” for academics) going on between the “optimists” and the “pessimists” on this very question since the early 1980s.

Lindert and Williamson (1983) argued that real wages soared after Waterloo. Feinstein (1998) and Allen (2001) argued that real wages were stagnant from 1780 and 1830 and after that they rose much more slowly than output. Gregory Clark (2005) used new price evidence to argue that real wages grew more rapidly than Feinstein and Allen thought. Allen responded in 2007 by combining Clark’s price index with Feinstein’s nominal wage estimates to push the pendulum back towards pessimism.

Read Allen’s introduction to get a flavor of the fight back and forth:

http://economics.ouls.ox.ac.uk/12119/1/paper314.pdf

…

However, I would say that the consensus is that there is no consensus. For Piketty to say otherwise is interesting.

Now normally, when you have an academic book from Harvard University press, from a guy whom Larry Summers said should get a Nobel Prize for his work on historical inequality, versus some guy in the comments of a blog…you would trust the former on what the literature on historical inequality has to say. But I hope you’ll forgive me if I put my money on Sadowski.

I think Piketty’s fans at this point are treating his book as if it’s a commercial. Nobody gets upset when the ad man says, “Come to Piketty’s One-Stop Shop for All Your Class Warfare Needs. Our Data Can’t Be Beat!”

Full Review of Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century

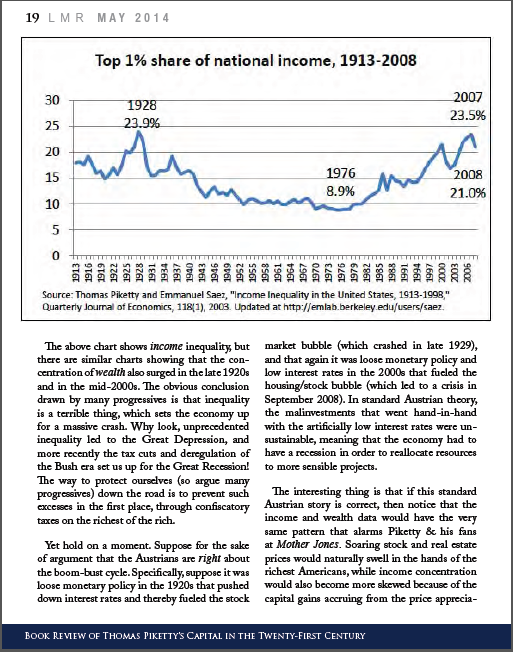

Carlos Lara and I put out a monthly financial magazine, the Lara-Murphy Report. In May I had a full-length review of Piketty. The best way I could think to showcase it here, was to do screen shots of the pages. So here ya go:

“These Austrians Are Funny Guys! Just Kill One of Them.”

Recently someone who is trying to get me a speaking job asked for some samples to wow & impress the event organizer. So since I had to dig these up anyway, here are some of the “funny…for an economist” clips I could remember. (Perhaps my all-time funniest, yet scholarly, talk was contrasting Austrian versus mainstream analyses during the crisis, at a Mises Institute event in Texas. But unfortunately an employee at the hotel turned off the microphone feed in between speakers and so that talk lives only in the memories of those who adored it live.)

So anyway, for all of these, I’m not saying you should watch the whole thing, but the opening remarks were better than average:

Audio Book Bask

What do they do in audio books that have a lot of tables (with numbers, I don’t mean furniture)? I ask because I know an author who is doing an audio book for his self-published book, and it contains–you guessed it–a lot of tables, and these are fairly important to his argument.

Recent Comments