Music City Friends of Liberty Pay Tribute to the Liberty Movement

Here you go kids, this should get you fired up for the New Year at work:

God’s Sovereignty and Free Will

One of the most difficult things about the God of the Bible is that He’s sovereign (meaning everything happens according to His will and indeed His design) yet we humans have free will and deserve any punishments meted out to us.

During my Bible study session today we covered Genesis 15, and there was a passage that I think sheds light on this tricky issue:

12 As the sun was setting, Abram fell into a deep sleep, and a thick and dreadful darkness came over him. 13 Then the Lord said to him, “Know for certain that for four hundred years your descendants will be strangers in a country not their own and that they will be enslaved and mistreated there. 14 But I will punish the nation they serve as slaves, and afterward they will come out with great possessions. 15 You, however, will go to your ancestors in peace and be buried at a good old age. 16 In the fourth generation your descendants will come back here, for the sin of the Amorites has not yet reached its full measure.”

I added the bold above. It sure sounds like God is saying something like, “I’m not going to tell my chosen people to wipe out the existing inhabitants and take the Promised Land just yet, for the existing inhabitants should be given more time to turn back from their wickedness–which they won’t do.”

For an analogy, at least this passage suggests that God is like a police officer who just knows the guy is guilty, but waits for him to officially commit a crime before arresting him, in order to satisfy all legal niceties.

P.S. Check out this commentary if you want to see someone else (presumably with much greater training than I have) discuss the same text and reach similar conclusions. An excerpt:

In other words, the promised land had been dominated by an exceptionally cruel and bestial culture for hundreds of years. The Amorites who dominated that land practiced such abominations as the slaughter of virgins and first born children in sacrifice to appease their gods. They were a people who callously tortured and destroyed with long lingering deaths both men and women whom they considered their enemies. They were a nation whose morals and scruples were paper thin. They lived like that for centuries and we have proof of that from archaeology. They were a blot on human history. They were a stench in the nostrils of God, and yet we are told that he did nothing about this for a long time. Why was that? How could the

righteous Lord sit back and do nothing? Surely it matters to him how creatures made in his own image behave? Don’t they live and move and have their being in him, sustained by him? Isn’t their breath in God’s hands? Then how can he supply the energy to hurt others so unspeakably? Surely he should smite them down at once? That is the issue before us, and here we find the divine explanation.Remember it is God who is speaking, not Abram. We may not escape from this question with the answer that God is simply helpless, wringing his hands in horror but unable to intervene. There is no doctrine of the so-called ‘openness of God’ taught in the Bible. It is quite clear from his words to Abram that God knows all that is going on. Nothing escapes the one who hates sin, yet God is waiting patiently for a certain moment in their history, a time when the wickedness of these Amorites has reached its full measure. That is, a time comes both for individuals and for civilizations when God says, “That’s it! Enough!” Until that moment sinners are spared judgment. They are benefiting from the longsuffering and patience of God.

My Inflation Bet: The Gift That Keeps on Taking

Don’t worry kids, I didn’t make another bet. Rather, this was the original wager that David R. Henderson then tweaked (including making the time horizon shorter). I am mailing the check to Bryan this month.

If you want to hear my thoughts on what went wrong, here is my indignant reaction to Krugman and DeLong, and here is my calm contribution in a Reason symposium on people who made faulty warnings about consumer price inflation.

The Fed’s (Belated) Birthday

This ran on the actual anniversary, but I think I forgot to post it here. Anyway, my take in the Daily Caller on the Fed.

Tom Woods and I Short-Sell Krugman’s Analysis of the Housing Bubble

Tom and I give an Austrian take on the bubble.

Step #3 In My Dispute With Beckworth: Moving From Davie on Interest Rates to David on Interest Rates

First, a recap:

==> In Step #1 I made the obvious point that if an employer in late October says that the paycheck will be $1000 higher in November than previously expected, and the paycheck in December will be $700 higher than previously expected, that clearly this is a more generous policy, relative to the path expected the moment before the announcement. The fact that workers now expect a $300 pay cut in December, relative to November, is misleading and irrelevant. What matters is that the workers are getting more money in each month relative to the original baseline. The month-to-month movements in the new path per se aren’t important when deciding whether the information indicates a “looser” vs. “tighter” pay policy. Nobody gave me any argument here.

==> In Step #2, we tweaked the example so it was dealing with the employer’s interest rate policy, rather than paychecks. By analogy with wages, I argued that the important issue was whether interest rates were lower than the originally expected level in each unit of time (either month or the year as a whole). The fact that workers might expect interest rates to rise more quickly later in the year is misleading and irrelevant. What matters is that the workers are paying lower interest rates in each month (or year for the whole) relative to the original baseline.

After some clarification, again, nobody gave me any argument here, in the hypothetical scenario as I constructed it. To be sure, David R. Henderson was getting ready to say that interest rates aren’t a good indicator of monetary policy, but even he conceded that *if* we are going to say “lower interest rates means looser money” and “higher rates means tighter money” then the correct baseline is to look at the originally expected path. It is clearly nonsensical to merely look at the change down the road, if that change still puts us at a lower interest rate. That would be analogous to our Step #1, when Davie argued that the $300 wage cut in December meant he was poorer, even though he actually was making $700 more than he originally expected.

==> Now we are finally at Step #3. (And sorry for the delay, I got sick during my holiday traveling and missed a window when I thought I’d knock out this post.) I am going to argue that David Beckworth in the real world has made a mistake very similar to what Davie in Step #2 committed.

Specifically, Beckworth back on December 10 made two empirical arguments to defend Ted Cruz’s claim that the Fed tightened monetary policy in the summer of 2008. In this post (Step #3), I will tackle the first of Beckworth’s empirical arguments. In the final Step #4, I will tackle Beckworth’s second empirical argument.

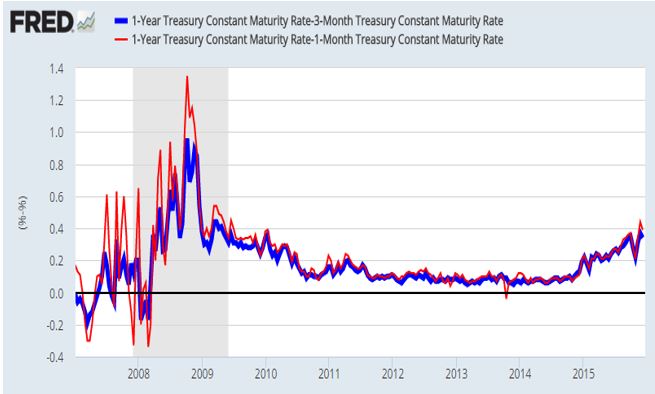

Now then, Beckworth’s first piece of evidence involved the following text and graph:

The [figure below] shows the 1-year treasury interest rate minus the 1-month treasury interest rate. Standard interest rate theory tells us that this spread equals the expected average short-term rate over the next year. That is, if the spread goes up in value then the market is expecting the short-term treasury rate to rise over the next year and vice versa. This figure shows a sustained surge in the expected short-term interest rate over the next year from April to November 2008. It especially intensifies in the second half of the year. Only in December does the spread really begin to fall. For most of the year, then, the market increasingly expected a tightening of policy going forward.

Now does everyone see how that is exactly analogous to Davie’s argument in my hypothetical scenario in Step #2? Specifically, Beckworth has shown–correctly–that the future increase in short-term rates expected by the market went up sharply during the fall of 2008. (It’s not as clear to me what happened before the fall, since the lines bounce violently up and down.) Beckworth seems to believe that his demonstration was the same thing as demonstrating that the market expected higher short-term rates later in the year, compared to the originally expected path.

But we know that in general, those two claims are not equivalent. That was the whole point of my (obviously contrived) scenario in Step #2; I wanted to make it crystal clear that in principle, those two things are not equivalent. If you have lost me here, I urge you to go back to Step #2 and look at the two graphics boxes, and see the distinction. Specifically, the market can simultaneously (A) expect rates to increase more during the year than previously expected and (B) expect future short-term rates to be lower than previously expected.

How is this possible? Simple: If all expected short-term rates drop for the next year, but the closer ones drop more than the further distant ones. Then you get the result that (A) the market expects rates to climb more during the year than it expected as of yesterday and (B) the market expects rates in, say, 8 months to be lower than it expected as of yesterday.

So why do I think that in the real world, this is what happened with Beckworth’s numbers? Well, in the chart below I decompose the spread. That is, I show not just the spread between the 1-year and 1-month Treasury bill yields–which is the red line in Beckworth’s chart above–but I also show the actual values of the 1-year and the 1-month yields:

However, my FRED chart has more information than Beckworth’s. In particular, the spike in the green line in September occurred because short-rates dropped (my red line) sharply, while one-year rates (my blue line) only dropped modestly. So since one-month rates collapsed while one-year rates fell more gently, I think this is similar to what happened in my contrived Step #2 example. Yes, the spread widened and we can interpret that as saying, “As of September 2008, the market expected one-month rates to rise more rapidly over the next 12 months than the market expected as of August 2008,” but that’s not the same thing as saying, “As of September 2008, the market expected the one-month Treasury yield in August 2009 to be higher than the market expected as of August 2008.”

==> In my Step #4–the final in this series–I’ll deal with Beckworth’s second empirical argument, and in so doing I will also shore up my position for this Step #3. Specifically, we will look at futures contracts to back out actual implied market forecasts of certain types of short-term rates in future months, at various points along 2008.

==> Last point for purists: Even my FRED graph is consistent with the claim that the Fed led markets to believe it would tighten and/or was actually tightening, from about March 2008 through June 2008. (That’s because the blue and red lines are both rising during this period, meaning that short rates were rising and the market thought future short rates would follow suit.) But that pattern turned around in June, when the blue line began its gradual fall for the rest of the year. So this is the exact opposite of what Ted Cruz needs for his version of history to make sense. In other words, if you want to argue that the Fed was giving winks to the markets to lead them to think tighter policy was in the works from March to June 2008, but then in June the Fed said, “Ha ha fooled you, actually we’re loosening,” then my FRED chart is consistent with that narrative. Yet that’s the exact opposite of what Cruz said happened, and thus the opposite of what David Beckworth said he was explaining with the Treasury yield curve data.

Contradicting the Ghost of Sumner Past

Poor Scott has been worried that I’m forgetting him with my running series on David Beckworth. But I couldn’t do that to the most prolific Market Monetarist blogger! So two quick observations on his recent posts. (And barring a marathon Euchre tournament, I’ll do Step #3 in my Beckworth series tonight.)

==> In his most recent EconLog post, Scott complains of his fellow economists who “lack an imagination.” In particular Scott writes: “I often find it hard to even have a conversation with my fellow economists. Sometimes their views on “scientific” methodology are so narrow that any claim that doesn’t fit some arbitrary mathematical model is ruled out of order.”

I agree! Now Scott was talking about behavioral economists, but there are money/macro guys guilty of this sin, too. For example, I know a guy who says that if your analysis of an economy dealing with 330 million people can’t be reduced to two lines intersecting on the x-y plane, then it’s bunk. How would you feel about a heart surgeon or car mechanic with this approach?

==> You think I’m kidding, but I’m being serious: I also totally agree with Scott’s second-last post at EconLog, titled, “The Fed doesn’t have a magic wand.” Scott wrote:

Here are the monetary base and interest rates on August 1, 2007:

MB = $855.960 billion, fed funds rate = 5.25%

And here is the same data on April 9, 2008:

MB = $855.411 billion, fed funds rate = 2.25%

Why did interest rates fall sharply? Perhaps one is entitled to say the Fed caused rates to fall, in the very limited sense that some counterfactual policy would have produced a different path for interest rates. But one is not entitled to also call that an expansionary monetary policy, even though expansionary monetary policies do in fact sometimes cause interest rates to fall. [Formatting in original.–RPM]

Again, I love it. But not just for its own sake, but because with some minor tweaks I can apply the above-quoted stance from Scott to help out with my dispute with a certain Market Monetarist. Watch how I can make totally plausible tweaks to spit out an analogous view:

Here are the monetary base and NGDP levels on August 1, 2007:

MB = $855.960 billion, NGDP = $14.6 trillion

And here is the same data on August 1, 2009:

MB = $1,677.1 billion, NGDP = $14.4 trillion

Why did NGDP growth fall sharply relative to the previous trend? Perhaps one is entitled to say the Fed caused NGDP growth to fall, in the very limited sense that some counterfactual policy would have produced a different path for NGDP. But one is not entitled to also call that a contractionary monetary policy, even though contractionary monetary policies do in fact sometimes cause NGDP growth rates to fall.

It’s the same thing as Sumner’s view, right?

Long Lay the World, In Sin and Error Pining

That is my favorite line of any song. For many people, their revulsion at Christianity has little to do with the miracles, but instead that they’re offended to hear that they need a Savior.

Recent Comments