Did Jesus and the Early Christian Church Renounce Violence Against Non-Believers?

Bryan Caplan is sure that they didn’t. In a recent post at EconLog, he first quotes Nathan Smith who wrote:

The Old Testament, to be sure, contains some hair-raising passages that seem very much opposed to religious freedom, but that’s part of the Mosaic law, which St. Paul’s epistles clearly and insistently establish is not comprehensively binding on Christians, but has been superseded, fulfilled, replaced by the higher ethical teachings of Jesus. The early Church never used violence.

Bryan disagreed. In fact, Bryan didn’t merely say, “I think this is slightly inaccurate.” No Bryan said, “Nathan grossly overstates the incompatibility between Christian doctrine and religious violence,” and then went on to write:

Yes, St. Paul did “clearly and insistently establish” that the Mosaic law “is not comprehensively binding on Christians.” But he focuses almost entirely on dietary requirements, circumcision, and the like. If Paul (or Jesus) meant to spearhead a culturally novel rejection of religious violence, he would have explicitly said so. And to make “The early Church never used violence” true, you would have to torturously gerrymander both who counts as “the Church” and when counts as “early.” [Emphasis in original.]

I must admit I was surprised by Bryan’s reaction, especially how confident he was with his claims. I’m going to list a bunch of Bible passages referring to the views of Jesus and Paul, but first I like how Joseph Porter in the comments responded to Bryan’s claim about the early Church:

…I am not aware of any violence perpetrated by any Christian—Orthodox or not—between the time of Jesus’ death (AD 30/33) and the rise of Constantine almost 300 years later. (The earliest Christians, in fact, certainly sound quite opposed to violence.) And I’d say “any self-identified Christian” and “almost 300 years” aren’t tortuous construals of “the Church” and “early.” Of course, my knowledge of the early Church is not encyclopedic—do you have some particular act (or acts) of violence in mind committed by “the early Church”?

Regarding Jesus, there are a bunch of things I could cite, but just some obvious ones:

==> From the Sermon on the Mount He taught, “Blessed are the meek,” “Blessed are those who show mercy,” “Blessed are the peacemakers,” and let’s quote this one in full: “Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. 12 Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

And then we must quote in full starting at verse 38:

38 “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.’[h] 39 But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. 40 And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. 41 If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. 42 Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.

43 “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor[i] and hate your enemy.’ 44 But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, 45 that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. 46 If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? 47 And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? 48 Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

Does Bryan really think Jesus needed to say, “By the way, if you encounter someone who doesn’t proclaim that I am Lord, I don’t want you to stab him”?

And in one of my most favored Bible passages, where we see the combination of Jesus as both merciful and an irresistible force, He rebukes Peter for drawing his sword when the mob assembled by the chief priests comes to arrest Him (after Judas led them there). Here’s what Jesus had to say about Peter using violence to try to prevent this injustice:

52 “Put your sword back in its place,” Jesus said to him, “for all who draw the sword will die by the sword. 53 Do you think I cannot call on my Father, and he will at once put at my disposal more than twelve legions of angels?

If you’re just skimming and the above didn’t do anything for you, you need to stop and re-read it. That passage makes my eyes water.

Now you might say, “Well that’s not really fair Bob, because sure Jesus can call down angels but we can’t. What did Jesus tell His followers to do when they encountered non-Christians?”

Try this passage:

16 “I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves. 17 Be on your guard; you will be handed over to the local councils and be flogged in the synagogues. 18 On my account you will be brought before governors and kings as witnesses to them and to the Gentiles.

And how is the world to identify a follower of Christ? “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.”

But here’s the clincher. Jesus did do exactly what Bryan wanted. Look at this story from Luke 9:

51 As the time approached for him to be taken up to heaven, Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem. 52 And he sent messengers on ahead, who went into a Samaritan village to get things ready for him; 53 but the people there did not welcome him, because he was heading for Jerusalem. 54 When the disciples James and John saw this, they asked, “Lord, do you want us to call fire down from heaven to destroy them?” 55 But Jesus turned and rebuked them.

Is it any surprise to the reader of the book of Luke by this point that Jesus would have rebuked James and John for such a ridiculous suggestion? Would it not have been monstrously out of character for Him to agree with their idea?

As far Paul, read this one-and-three-quarters chapters on what he thinks about the people of Israel who have not accepted Christ. It’s too long for me to quote, but it’s impossible to read that and think violence is acceptable against non-believers.

For one thing, if you believe in Christ and are saved, you can’t be proud of yourself (according to Paul). You deserved hell as much as anybody who rejects Christ. So it would be weird to think that gives you the moral authority to kill somebody on that account. In any event, though you should click the link to get the full spirit of it, here’s how he wraps up. In context he is explaining how God is letting (some) Gentiles come to Christ to be saved, in order to goad the Israelites to come home:

Just as you who were at one time disobedient to God have now received mercy as a result of their disobedience, 31 so they too have now become disobedient in order that they too may now[t] receive mercy as a result of God’s mercy to you. 32 For God has bound everyone over to disobedience so that he may have mercy on them all.

So if you want to argue about the existence of hell and how arbitrary you think this system is, OK we can have that discussion, but there’s no way you could think Paul has left the door open for followers of Christ to spread the gospel with the sword.

UPDATE: It’s possible by “early Church” Bryan meant once the Catholic Church was up and running and had some earthly power. I could understand someone saying, “Oh sure, the Christians were all meek and humble when they were helpless, but once they had the ability they used violence to get their way.” Right, but my point is that just proves how humans are awful hypocrites. It doesn’t mean Jesus, Paul, or other writers in the New Testament were vague on using violence against non-believers.

Being a Liberal Means Never Having to Say You’re Forgiven

[UPDATE below.]

Now that Tom Woods and I have a hugely successful podcast analyzing Paul Krugman’s columns, I have hardly been paying attention to his blog posts. So while I was killing time today waiting for the Texas Tech parking lot to clear out after their heartbreaking buzzer-beater loss to Baylor, I got caught up on the Conscience of a Liberal. It reminded me why I’m not the man’s biggest fan.

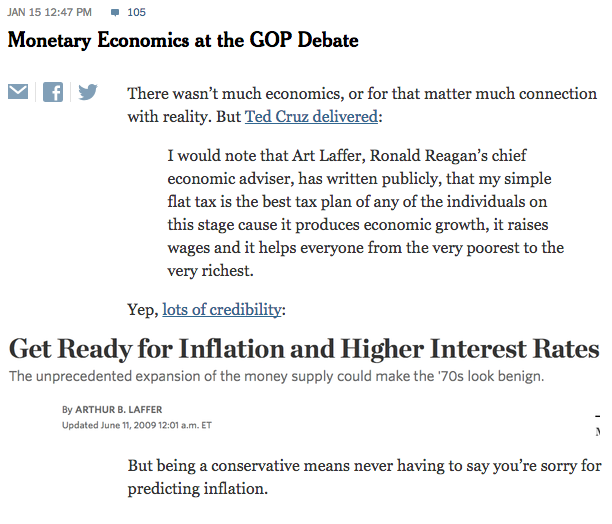

In order to make sense of his Jan. 15 post, I need to give you the screenshot:

So to be clear, Krugman is quoting Ted Cruz, then he’s posting a screenshot of a June 2009 Wall Street Journal column from Laffer predicting high inflation and interest rates, then Krugman comments, “But being a conservative means never having to say you’re sorry for predicting inflation.”

Now you know what’s funny about that? Two things. First, Ted Cruz was invoking Arthur Laffer’s authority on supply side tax cuts. That has absolutely nothing to do with monetary policy, and there is no one in human history more qualified to tell Republican voters which candidate’s plan is best from a supply-side perspective.

Second, Arthur Laffer did publicly acknowledge that his inflation predictions were way off, such that he would rethink his model. In other words, he did exactly what Krugman has been demanding such people do. And you can’t say, “Well, maybe Krugman missed that,” because Krugman publicly praised Laffer for doing so–in a blog post titled, “In Praise of Art Laffer,” and it was only two years ago. So you’d think Krugman might remember that one.

It’s because of stuff like this that it’s clear to me Krugman is completely insincere in his moral posturing and pleas for intellectual honesty. Yes, if writers (like me) made erroneous predictions about price inflation or anything else, we should be honest with our readers about what we think happened and how we’re trying to avoid such mistakes going forward. But the point certainly isn’t to curry favor with guys like Krugman. The only way to get on his good side is to switch to his policy prescriptions, which is why Kocherlakota is a good guy now.

UPDATE: After I posted the above, I saw at EconLog that David R. Henderson had similar remarks, though he pointed out Krugman’s (with Larry Summers) own warnings of an inflation time bomb (the actual phrase they used) in the early 1980s.

Potpourri

==> For those in the Houston area, I’m going to be at the Mises Circle on January 30. Other speakers include Ron Paul, Lew Rockwell, and Jeff Deist. Details here.

==> Speaking of the Mises Institute, they’re trying to get updates from any alumni who have been through Mises U.

==> A lot of people were passing around this FEE piece by Daniel Bier on Powerball, which was fine as far as it went. Yet it too overlooked the pretty simple (but important!) point I made: That if the pot gets so big that “now it’s a good bet,” everyone else can do the same arithmetic and would also buy a ticket, if that were actually the full story. In other words, the probability of splitting the pot with someone else goes up, the bigger the pot gets. And sure enough, there were three winners. If you look at the history of Powerball jackpots–assuming I’m interpreting the results correctly–the jackpots with multiple winners tend to be large. For example, in 2015 the biggest jackpot was the only one that was split (three ways). In earlier years the pattern isn’t perfect but it’s pretty close. Of course, ideally you’d really want to test to see how many tickets were sold, as a function of jackpot size, but I think looking at the actual splits is pretty good to make the point that the probability of splitting is clearly not independent of the size of the pot.

==> This was a really good–and hilarious, near the end–Glenn Greenwald piece on the U.S. media’s treatment of the Iranian government seizing American sailors.

Mystery Explained

Thanks to Captain Parker and E. Harding, they were telling me the answer to my previous query, but I was not receptive until yesterday for some reason.

Here’s a chart showing the drop in official “total reserve balances” and how it is largely explained by a rise in Treasury deposits (with the Fed) and reverse repos (that the Fed engages in with Federal Home Loan Banks and other institutions that aren’t eligible to receive interest on reserves):

So, it’s not that reserves are leaving the banking sector, it’s just that some are being held in different ways that don’t get counted in the normal metric.

For a great explanation of the mechanics/accounting of how the Fed is actually raising interest rates, see this Econbrowser post by James Hamilton. (Again, thanks to Captain Parker for the link.)

Federal Reserve Banks: Total Assets vs. Reserve Balances

Here’s something interesting, possibly disturbing, that I just noticed while prepping for a radio interview:

The red line shows that since the “taper” ended, the Fed has been treading water with its assets, rolling over bonds as they mature but not letting its total holdings drop.

On the other hand, the blue line shows the total reserves in the banking system. I’m not sure why it bounces around so much, or why it has dropped ~$230 billion since late December. There is no seasonal adjustment on the blue line, but the other dips didn’t occur in Dec/Jan.

Any thoughts?

Inverted Yield Curve and Recessions

The 3-month and 1-year Treasury yields have gone way up in the past year, but the overall spread (say between them and the 10-year) is still quite positive, so the classic warning of an impending recession is still not here. Here’s a long-term chart:

In the chart above, the red line is the 10-year yield, the green line is the 3-month yield, and the blue line is the difference between them.

So, if you just look at the blue line and the recession bars, you can see that the blue line always goes negative before a recession.

But by decomposing it, you can see that specifically what happens is that short rates zoom upward to exceed long rates. (In principle the yield curve could invert if long rates collapsed below short rates. But this chart shows, that’s not how it actually happens historically.)

In this paper, I argue that the Austrian business cycle theory, among its other virtues, can explain the predictive power of the yield curve. Specifically, central banks have more control over short rates than long rates. So in standard Austrian theory we say the central bank “raises rates” and this causes the boom to turn to a bust. Well, when you get more specific about it, that would mean short rates go up while long rates (which are a combination of expected real growth and price inflation) will stay put or possibly even go down.

So, if you buy the basic story of ABCT, then out pops the fact that an inverted yield curve “predicts” recessions as a bonus.

** For a full explanation of the Austrian theory of the business cycle, see my new book Choice from the Independent Institute.

Potpourri

==> I realize I am trained at this point to perceive tension between our popular Keynesian writers, but isn’t there a problem reconciling this DeLong piece with this Krugman op ed?

==> This Vox piece is happy to report that (apparently) employers aren’t penalizing full-time work in response to ObamaCare mandates as many analysts (including me) warned would happen. Yet look at this part in particular:

But [the study] also tries to dive a bit deeper and look not just at the overall economy but at very specific subgroups that seem more likely to be affected. This includes people who work just above 30 hours per week and don’t get insurance at work, who might see their hours cut to dodge the employer mandate. Or workers who gained Medicaid coverage — and might be less inclined to keep their job now that they have an alternative source of health insurance.

But Simon says that neither of those groups showed a clear employment pattern. Take the group that worked just above 30 hours per week and didn’t have insurance in 2013, right before Obamacare hit. Their hours went down a little bit in 2014, but bounced back in 2015 to 2013 levels.

“These are the people right on the margin, and we’re not showing any clear trend,” Simon says.

This is really incredible. To their credit, the people associated with the study–and others quoted in the article–are being very guarded about the results.

But in light of the gleeful tweets from people like Noah Smith, I have to ask those who ridicule people warning about minimum wage/ObamaCare: Suppose the federal government said employers had to pay an additional $5,000 for every racial minority on their payroll. Would it be crazy for civil rights groups to get upset about that? Would you say we need to go run some regressions a few years after the experiment?

Recent Comments