John Lennon Was Cooler Than I Realized

I love every part of this excerpt, especially the very end. (HT2 JH Huebert)

Call me crazy, but is Yoko citing Say’s Law??

Is Krugman Just Lying Now?

I read Krugman’s latest NYT op ed in amazement. It seems this notion that “it’s a myth Obama is trying to expand government” is catching on. Look at this excerpt:

Here’s the narrative you hear everywhere: President Obama has presided over a huge expansion of government, but unemployment has remained high. And this proves that government spending can’t create jobs.

Here’s what you need to know: The whole story is a myth. There never was a big expansion of government spending.

OK, so at this part you think we’re just quibbling over “big expansion,” right? In other words, you expect Krugman to go on to argue that yes, government spending went way up when Obama came into office, but it was too little, too late.

But no, that’s not what Krugman says. Look:

Ask yourself: What major new federal programs have started up since Mr. Obama took office? Health care reform, for the most part, hasn’t kicked in yet, so that can’t be it. So are there giant infrastructure projects under way? No. Are there huge new benefits for low-income workers or the poor? No. Where’s all that spending we keep hearing about? It never happened.

To be fair, spending on safety-net programs, mainly unemployment insurance and Medicaid, has risen — because, in case you haven’t noticed, there has been a surge in the number of Americans without jobs and badly in need of help. And there were also substantial outlays to rescue troubled financial institutions, although it appears that the government will get most of its money back. But when people denounce big government, they usually have in mind the creation of big bureaucracies and major new programs. And that just hasn’t taken place.

Consider, in particular, one fact that might surprise you: The total number of government workers in America has been falling, not rising, under Mr. Obama. A small increase in federal employment was swamped by sharp declines at the state and local level — most notably, by layoffs of schoolteachers. Total government payrolls have fallen by more than 350,000 since January 2009.

Now, direct employment isn’t a perfect measure of the government’s size, since the government also employs workers indirectly when it buys goods and services from the private sector. And government purchases of goods and services have gone up. But adjusted for inflation, they rose only 3 percent over the last two years — a pace slower than that of the previous two years, and slower than the economy’s normal rate of growth.

So as I said, the big government expansion everyone talks about never happened. This fact, however, raises two questions. First, we know that Congress enacted a stimulus bill in early 2009; why didn’t that translate into a big rise in government spending? Second, if the expansion never happened, why does everyone think it did?

Part of the answer to the first question is that the stimulus wasn’t actually all that big compared with the size of the economy. Furthermore, it wasn’t mainly focused on increasing government spending. Of the roughly $600 billion cost of the Recovery Act in 2009 and 2010, more than 40 percent came from tax cuts, while another large chunk consisted of aid to state and local governments. Only the remainder involved direct federal spending.

And federal aid to state and local governments wasn’t enough to make up for plunging tax receipts in the face of the economic slump. So states and cities, which can’t run large deficits, were forced into drastic spending cuts, more than offsetting the modest increase at the federal level.

…

But if they won’t say it, I will: if job-creating government spending has failed to bring down unemployment in the Obama era, it’s not because it doesn’t work; it’s because it wasn’t tried.

OK upon my second reading, I think I see his escape hatch. But c’mon, a casual reader would surely conclude from the above that total government spending had actually dropped because of the recession, right? That yes, federal spending went up a bit, but it was more than offset by the decline in state & local spending.

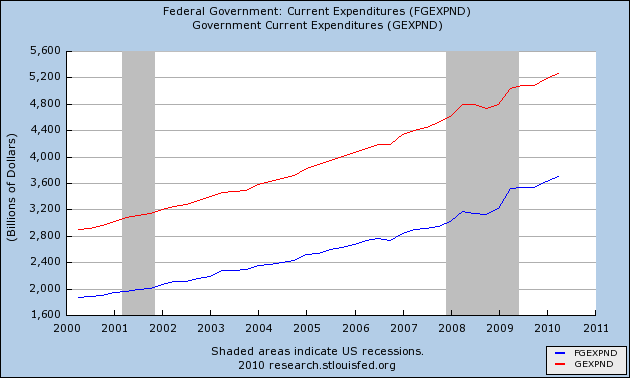

Except, that’s not what happened, at any point in this recessionsince Obama was elected, at least according to the seasonally-adjusted quarterly figures put out by the trusty bureaucrats:

Thoughts on Hell

Aristos writes to me with a suggestion for today’s post:

[H]ow about addressing this one that [my daughter] brought me. God loves us so much that he sent his Son to die a painful and humiliating death. He knows that we are “screwed up,” so why does He hold the threat of Hell over our heads? She asked me if, once everything was revealed, anyone would deny God’s majesty. I said “I doubt it,” to which she said, “Then the idea of Hell is unfair, for in the end all is revealed.”

It made me think. Either there is no Hell, or God is not so merciful.

This is of course a tough one. (Though for me personally, the toughest one is God ordering the Israelites to kill babies. Yikes.)

OK, if we take the Bible at face value, then Aristos was right to tell his daughter that everybody would know exactly what the deal was, after death. There are at least three passages saying that, at some point, every knee shall bow and every tongue shall confess to God. And of course, if the events described in Revelation come to pass, even Christopher Hitchens might raise an eyebrow.

So I would agree with Aristos and his daughter, that everybody will realize upon death that the Christians were right. (Of course, I am assuming for the sake of argument that…the Christians are right. What we are doing in this post is exploring whether God is fair, if reality is structured the way that Christians believe it to be.) Incidentally, this doesn’t mean that every Christian is going to say, “Ah, God is just as I imagined Him.” Of course not; our puny minds can’t possibly comprehend a Being of infinite power, goodness, and intelligence. (Personally, I can’t decide if I would find it horrifying or hilarious if God ended up looking like Alanis Morissette.)

So here are some of my thoughts on this issue:

* It seems that the critics of God want it both ways. On the one hand, they are mad that He allows bad things to happen; why does He let bad people get away with stuff? But on the other hand, they are mad that God ultimately punishes the bad people.

* If we are going to have any type of free will, then it seems the world has to have the general attributes that it currently does: Evil is seductive and advantageous in the short-run, but it is actually self-destructive in the long-run. Now a lot of evil’s corroding effects take place even in this world, but ultimately things get settled up–good is shown to be the right course of action–in the next world, for all of eternity.

* There are several places in the Bible where “doing God’s will” is likened to an intellectual feat. In other words, person A obeys God not because he’s a “good person” but because he knows something that person B, who disobeys God, does not know. (For example see my favorite verse.) So in this sense, our time in this world really is a test, in every sense of the word. Yes, after the teacher grades our answers, we’ll all get our scores back and see if we passed. Everyone will know, at that time, if he or she did well on the test.

* Now if we were bound under the Mosaic law, then I think Aristos and his daughter might have a valid point. It does seem a bit unfair that an omnipotent being sets up this system, whereby we have to follow an incredibly complex set of rules or else get punished for eternity.

* However, evangelical Christians (I can’t speak for other groups) think that, in a sense, we had the coolest TA ever come to our study group before the big exam, and he gave us the answer to every question. Instead of answering the really tough questions, we just have to put, “See the work of the TA,” and the teacher will give you credit on it. So yes, if that TA had never shown up, then the whole thing might seem horribly unfair. But with the TA–and the teacher knew all along he’d send the TA to help his students–things are radically different. (This analogy works on some levels, but not on others. Discuss.)

* OK but let’s get down to the nitty-gritty: How in the heck is it fair for God to threaten eternal torment, especially when a lot of people don’t believe in Him for purely intellectual reasons? In other words, why should they be punished for an honest mistake?

Well this is a tough one. Here’s a few things. First of all, I view hell as the absence of God. In other words, if you die and “go to heaven,” what that really means is that you are in the intimate presence of God Himself, for all of eternity. (If that’s not heaven, what would be? Heaven could be nothing more nor less than that.)

So, if that’s what heaven is, then I think all hell “need” be is that you spend the rest of eternity not with God. You sit there and sulk in your own narcissism, forever. Yes, you’re “free” and “independent,” and you realize that it is pure agony.

I admit I do not fully understand it all. There are plenty of things that seem questionable to me about God’s plan. But part of what I mean when I say I “have faith” is that I trust in the character of God. More specifically, I trust the character of Jesus. The guy who spoke the parables, the sermon on the mount, and so forth, was definitely a much better man than I am. And He said that no one is good except God, i.e. the same person who did some pretty serious things in the Old Testament.

As far as the narrow point of current atheists being honestly unaware that God exists, all I can say is this: Now that I have flipped, I find my previous views to be shockingly simplistic. I can remember how confident I was that I had “blown up” my Christian friends’ worldview, and in retrospect I can’t believe I didn’t see the invalid leaps in my own position.

So that’s partly why I write these Sunday posts. I want to disabuse current atheists of the idea that “only morons could possibly be Bible-thumpers.” Maybe I’m totally wrong, but this isn’t something you can dismiss in a few moments. For sure, studying science does not automatically lead one to reject the existence of God.

Speaking of which, if any cynics want to point me to digestible blog posts or articles attacking either Christianity or theism in general, I’d be happy to try to tackle them in upcoming Sunday posts. I’ve got one in the queue already.

I Have Never Felt So Irrelevant

The dystopian von Pepe sends me Karl Smith’s taxonomy of various explanations of the business cycle, which I’ve seen people linking but I hadn’t actually read. The following excerpt took the wind out of my sails:

Recalculation

There are some people, I am thinking Arnold Kling here, who believe in what I might call a neo-Austrian view. I don’t think there are any formal models here and I might be mistaken but I think many in this camp eschew formal models. What there is, is a basic sense that markets work as an evolutionary process.

Within that process transitional pains are to be expected and recessions are just a big version of that. Arnold is currently the most vocal intellectual in this School but if you had to nail down what the Peter Schiffs of the world are thinking, its probably closest to something like Recalculation.

If anyone says that the government caused a bunch of people to buy houses they couldn’t afford and now we are working through the pains of that, they are effectively a Recalculationist.

In summary, for these guys recessions are caused by mistakes which take time to be corrected. There is no treatise as such but you can try:

And then if you click on the link–which yes, in this day and age is an unclothed URL, which simply gives me the willies in its indecency–you go to a google search for Arnold Kling’s various posts at EconLog on “Great Recalculation.”

What’s really so depressing about this, is that this guy Smith is obviously not trying to put down the Austrians. Go read his post; he’s really just trying to honestly answer Ezra Klein’s question about the different models for explaining the business cycle.

Yet Smith either doesn’t know about the various treatises laying out the Austrian theory of the business cycle, OR, he thinks they are so useless that Ezra Klein should just go read Kling’s blog posts.

This isn’t just a failure of Mises.org, it’s also a failure of the GMU guys. I mean, why doesn’t Smith know about Tyler Cowen’s book on Austrian business cycle theory?

I haven’t felt like this since high school.

Volokh Conspiracy Throws Brad DeLong Into the Briar Patch

Ah, yet another missed opportunity in the geeconosphere. Today during my lunch and dinner breaks–I drove to Auburn for the Supporters Summit starting tomorrow–I read a string of blog posts initiated by a link from Arnold Kling.

At first I was very excited. Continuing his war of choice against Todd Henderson–a U of C law professor who has a high income but doesn’t feel he is “rich” and so shouldn’t pay higher taxes–DeLong really stepped in it. His post was so over-the-top that, handled properly, I actually think even some of DeLong’s faithful would have questioned the Dear Leader’s magnanimity and evenhandedness.

But alas, “our side” managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. This will be a bit cumbersome for me to convey to you folks, but picture me as George Washington explaining why we’re all freezing our butts off in Valley Forge. This is important stuff–and maybe I’ll inspire one of you to write, “These are the times that try bloggers’ fingers…”

OK, so let’s start at the beginning. Brad DeLong gave a list of nine points about Todd Henderson that causes him to “marvel.” DeLong’s ninth point was, “I genuinely do not understand why Henderson has his job.”

So what’s DeLong’s beef? Well, you need to know that Henderson was (until recently) a blogger at “Truth on the Market.” Whether because of the controversy caused by his woe-is-me-I-only-make-$450k-a-year stuff or not, Henderson has recently hung up the keyboard and called it quits.

In a going-away tribute, Henderson’s fellow blogger J.W. Verret wrote:

I am saddened that our co-blogger Todd Henderson is putting up his blogging hat. He leaves us with an academic reputation that is unsurpassed, unfortunately I can’t say that the reputation of everyone involved has held up very well in light of the very personal nature of attacks…. I do think, however, that this is a good opportunity to focus the world on the wide range of scholarly work from Professor Henderson…. Here are a few papers of his on ssrn worth reading (this certainly won’t be the last time we link to his work at TOTM [Truth on the Market]):

In “Insider Trading and CEO Pay,” Prof. Henderson examines the effectiveness of insider trading as a compensation device using a study of 10b5-1 trading plans. His findings are in line with Henry Manne’s original thesis from nearly 40 years ago that insider trading didn’t diminish firm market value on net and may serve a useful purpose as an executive compensation device to motivate managers to maximize the value of the firm…

OK, stay with me kids–like I said, this is important. (Not because of the content of the disagreement, but because of the poorly executed attack.)

After quoting the above farewell from Verret, DeLong says (and I reproduce it in its entirety):

To which my first reaction is simply: Huh?!

And my second reaction is: No! No! No! Ten-thousand times no! That is simply wrong.

Giving firm managers the freedom to use information they privately have as a result of their jobs to decide when to buy and sell shares of stock does not motivate managers to manage the firm in the interest of shareholders.

If managers free to engage in insider trading know that the next piece of news to be released will cause the stock price to rise, they will buy. If they know that the next piece of news to be released will cause the stock price to fall, they will sell and then buy back later. They don’t care whether the news is good or bad–either way they will profit, and either way they will profit equally.

What the ability to engage in insider trading does is that it gives managers an incentive to make the price of the stock vary–they don’t care which way. Thus it cannot “serve a useful purpose as an executive compensation device” and cannot “motivate managers to maximize the value of the firm” to shareholders.

Insider trading makes executives’ portfolios’ long not the company but long the volatility of the company. And shareholders don’t want executives making decisions that make the value of companies they own more volatile: stock market investments are risky enough as it is without giving executives reasons to boost the volatility pot.

This claim that freedom to engage in insider trading aligns executives’ interests with those of shareholders is so basically wrong, so obviously erroneous, so simply stupid that–well, words fail me.

OK. Well. Clearly here, DeLong has overstepped. He is dismissing an entire literature as stupid–in fact so stupid, that someone who writes a paper within this literature ought to be fired.

So far, so good. I am not the only one who can see DeLong has just wound up and punched the tar baby square in the jaw. Jonathan Adler at the Volokh Conspiracy goes in for the kill, in a post featuring the fabulous title, “Why Oh Why Can’t We Have Better EconProf Bloggers?”:

Would you consider it sound for one academic to attack a paper written by another, calling it (among other things) “obviously erroneous” and “simply stupid,” based upon a third-party representation of what it says? And would you consider it responsible to use the third-party representation of said paper as Exhibit A for questioning why the author has a tenured job at a prestigious academic institution? You would if you were University of California at Berkeley economics professor J. Bradford DeLong, who has continued his series of attacks against University of Chicago law professor M. Todd Henderson. “I genuinely do not understand why Henderson has his job,” writes DeLong, pointing not to anything Henderson himself wrote but instead to what another academic blogger wrote about Henderson’s scholarship. [Yes, this is the same Professor DeLong who repeats baseless accusations against other academics and then, when asked to substantiate his charges, selectively edits his comment threads and then dissembles about said editing when called on it.]

According to University of Illinois law professor Larry Ribstein, DeLong’s attack on Henderson’s scholarship is quite off base:

the most remarkable thing about DeLong’s post is that it accuses Todd of being “stupid” and unfit for law teaching because of an argument Todd didn’t make!

If DeLong had bothered to look even at the abstract of Todd’s article, perhaps he would have noticed that the article’s not about alignment of incentives, but about whether boards bargain with insiders over their gains. Todd finds evidence consistent with the hypothesis that “boards pay executives in a way that reflects the profits they are expected to earn from informed trades.” . . .

I will leave it to the reader to decide what we should make of a Professor of Economics at U.C Berkeley, Chair of Berkeley’s Political Economy major and former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury who is willing, in print, to accuse somebody of being “simply stupid” for a position he does not take expressed in a blog post he didn’t write. [Bold added.]

Eek! Sorry guys, you just threw DeLong into the briar patch.

You guys were going great up until that last point. Yes, DeLong was being a jerk. Yes, he was being incredibly sloppy in dismissing an entire literature while shooting from the hip, especially given that it was his reason for questioning someone’s academic position.

But you guys went too far when you tried to argue, “And not only is DeLong wrong for criticizing that point, it’s not even in Henderson’s paper! In fact, all DeLong had to do was READ THE ABSTRACT to see that’s not what the paper was about!!!”

That sort of response would have been fantastic if (a) it were true and (b) the allegedly incorrect summary of Henderson’s paper had been written by, say, Paul Krugman. In that case, it would have been perfectly appropriate to bust DeLong on relying on the sloppy summary by an enemy of his target.

But no, in this case, what fellow Truth on the Market blogger Ribstein was saying is this: “DeLong should be ashamed of himself for thinking that Henderson’s paper made that argument, even though my fellow Truth on the Market blogger Verret thought that’s the conclusion that the paper supported when he was praising Henderson for writing it.”

In other words, if Ribstein is right, then that means Verret was either dumb or lazy himself. (Verret himself rolled with the punches and thanked Ribstein for pointing out the ambiguity in his original post. Nice attempt at damage control, Verret, but your teammates still turned the ball over.) We can hardly work up moral outrage against DeLong for taking Henderson’s fellow blogger’s praise as an accurate representation of Henderson’s position.

Because of this confusion, DeLong had an easy escape hatch. He simply quoted the paper’s abstract, and argued that it was consistent with Verret’s initial description, meaning that DeLong was perfectly fair in using that as the springboard of his criticism.

So now, instead of us being able to focus on DeLong dismissing a whole body of work with some quick syllogisms–and using that procedure to question a guy’s job–we are bogged down in trying to figure out who said what when. Someone who initially thought DeLong was right, would have no reason to spend 20 minutes getting to the bottom of this complicated mess.

One final point: Here’s the real travesty. It’s not as if DeLong didn’t exhibit any other weaknesses in his post. But because Adler and Ribstein thought they had the coup de grace, they missed the exposed jugular when DeLong wrote:

Henderson’s ignorance about American government policy. He talks about “the vast expansion of government [Barack Obama] is planning…” But if you look at the laws that Barack Obama has lobbied for and gotten Congress to pass, in the long run they don’t expand but shrink the government relative to what it would otherwise be. Quantitatively, the biggest legislative initiative by Obama so far has been very large long-run cuts in Medicare spending. Henderson is either so ignorant that he does not know this, or so mendacious that he doesn’t want his readers to know this. I bet on ignorance.

Just look at the part I put in bold, and marvel at what a slippery fellow this DeLong is.

But OK fine, let’s play by DeLong’s rigged rules. Even if we just look at the health care legislation, is it really true that it shrinks government? I am not going to bother looking it up, but I seem to recall that the reason ObamaCare was supposed to reduce the deficit was that it–and I’m making these numbers up–would increase spending by only $950 billion over 10 years, while it would increase revenues by $1 trillion.

So is DeLong right, even on the narrow terms that he wants to use in the above quote? Is it really true, say, that the CBO projections of total government spending through 2050 were higher in October 2008, than they are now? I find that hard to believe, but then again I am ignorant and mendacious.

Yet Another Murphy Twin Spin

I wrote this op ed commenting on the Fed’s turnabout in late August, but it just ran today on MarketWatch. It’s funny, I can really tell the difference between a regular newspaper versus this website; the edits that the WSJ people make are a lot more financially-savvy than those that “regular journalists” make. (BTW check out the comments to the article. They are pretty funny.)

Then over at Mises I talk about the claims (by Yglesias and others) that TARP “made the taxpayers money.”

Donald Duck Re-Enacts My Own Experience With Glenn Beck

Thanks to Sam T. for sending me this. It starts out a little slow in the first 2 minutes or so, but give it a chance. It’s really funny starting at about the halfway point.

Recent Comments