War Is Not Conservative

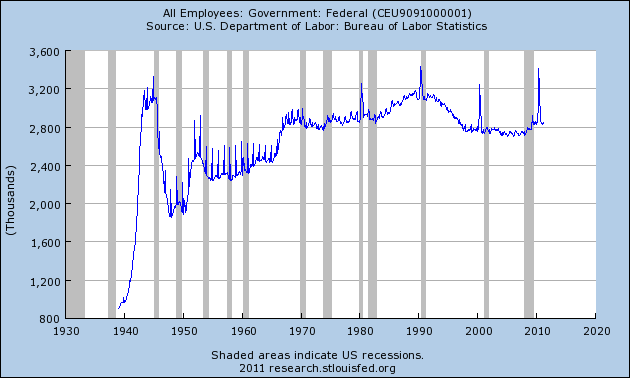

Brad DeLong linked to an interesting post by Karl Smith, which showed that total government employment has apparently gone down the last few quarters. (Note that I am not familiar with these data, so I can’t say whether they are accurate.) I wanted to see how much of the effect was due to state and local cuts, so I just asked FRED to show me the Labor Department’s tabulation of official federal employment. Check this out:

So I will admit that–if accurate–the employment growth under Obama is less than I would have thought. However, what’s more interesting is the incredible explosion going into World War II, and how Bob Higgs’ “ratchet effect” is in full force.

War is the health of the state. Tom Woods is right: If you believe in limited government, you should oppose the warfare state as much as the welfare state.

Paul Krugman, Inflation Denier

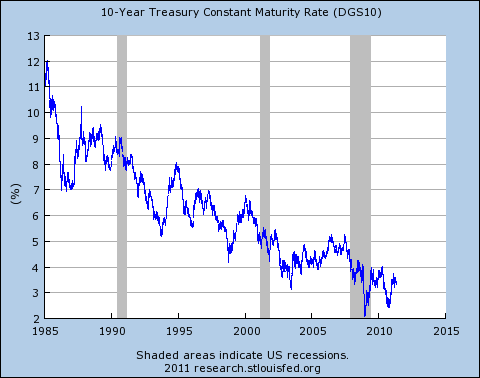

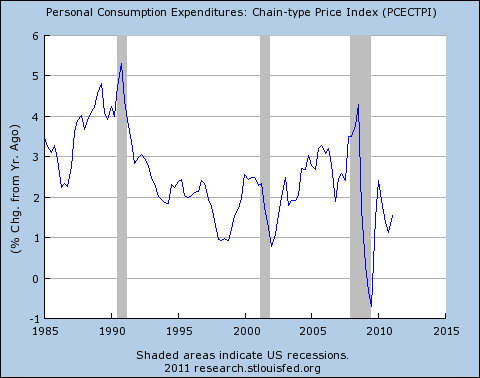

In a recent blog post, Krugman provides some graphs of the things “we’re supposed to be worried about,” which he means sarcastically. Namely, bond market confidence and (price) inflation. Here are the charts:

Then Krugman concludes:

A naive observer might note that interest rates are low by historical standards, making you wonder why we’re obsessing about the bond market; that inflation is also low by historical standards, making you wonder why it’s an issue at all; and that unemployment is immensely high. But Washington has its priorities.

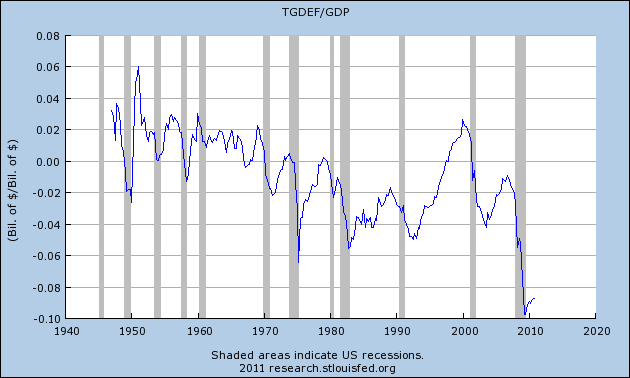

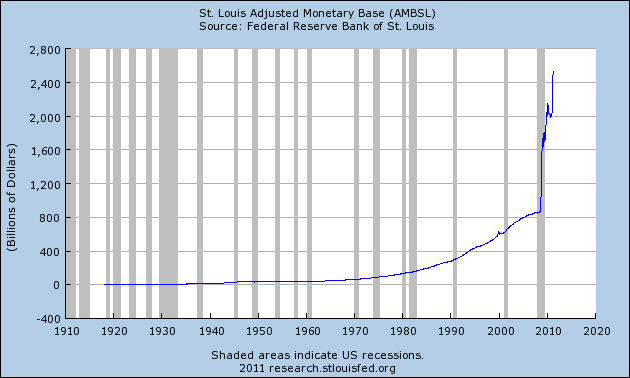

Hold on a second, Professor. It’s not as if those of us wringing our hands over the bond market and (price) inflation don’t have our own empirical reasons for alarm. To wit:

The first chart (i.e. third chart in this blog post) has an obscure title generated by FRED, but it is “Net Government Saving” divided by Real GDP. So it is basically showing how big the deficit is (a negative number) as a share of the economy. The second chart above (i.e. fourth and last in this blog post) shows the monetary base in absolute dollar terms.

So we see that the deficit as a share of the economy is the highest it’s been since World War II, while Bernanke’s monetary activities have literally been unprecedented and in fact have added more to the base in the last 3 years than humans have added since the Model T.

It is a basic tenet of economics that, other things equal, the more money you pump in, the higher price the price level. Indeed, we currently have the highest CPI in recorded history, and five of the years with the highest CPI were in the last five years.

Now Krugman can come up with all sorts of sophisticated models explaining why these basic theoretical and empirical trends aren’t really there. And I’m sure he and the other inflation deniers will pounce on that awkward email I sent to Bob Wenzel, saying that, “I used John Williams’ ShadowStats’ trick to hide the decline in core CPI.” That email line has been taken out of context and I assure all of you, Wenzel and I are committed scientists. A special commission set up by the Mises Institute has cleared us of any wrongdoing.

The peer-reviewed literature is on our side. Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. We have case studies of what happens when societies become saturated with too much money. Already we can see food riots around the world, and even in the United States people are hurting because of high gas prices and heating bills. How long will the inflation deniers bury their heads in the sand, and ignore the suffering their policies have wrought?

The truth will out, and we need to stop injecting so much fiat pollution into our banking system. Don’t let the Soros-funded deniers convince you that our reckless fiscal and monetary behavior is sustainable.

White House Releases Video of Bin Laden Capture

Turns out “SEAL Team 6” was one man. A very small man. (HT2 Viresh Amin.)

Family Guy Osama Bin Laden Clip (Banned from TV)

Tags: Family Guy Osama Bin Laden Clip (Banned from TV)

Potpourri

* Casey Mulligan and I apparently are alone on this issue of New Keynesians (I’m a cricket in the comments)…

* I think this was the first Megan McArdle post (on the neat creation of a fake MLK quote) that didn’t annoy me for some reason.

* Speaking of pacifism, here’s Tyler Cowen criticizing Bryan Caplan in a way that is very typical in this debate: He points to regions that are racked by war, and then uses these examples to “prove” how awful pacifism would be. Tyler could very well be right, of course, I’m just pointing out the structure of his argument. He can recognize all too well how goofy it is when Keynesians point to the fate of the 2009 stimulus package as “proof” of the multiplier.

* Brandon Harnish has a post up about the relationship between Christianity, economics, and libertarianism. I haven’t read it carefully yet, but I thought Major Freedom (recently promoted from Captain) needed a good jab going into the weekend.

* Speaking of religion and politics, this is a funny t-shirt.

* Here’s Mario Rizzo thoughtfully criticizing George Soros’ talk on Hayek. Here’s Tom Woods being a meanie.

* I had to document my claim (for a forthcoming response to James Galbraith that will run in the American Conservative) that Christina Romer had said the Obama stimulus package would keep unemployment under 8 percent. My google search led me to this Krugman post made in early January 2009, which I don’t think I ever saw before. Check it out. I think I may have been far too willing to buy Krugman’s version of history on this. Yes, he thought the stimulus should have been bigger all along, but in this post, does it sound as if he’s disputing Romer et al.’s claims about the unemployment rate?

* In the interests of balance, let me admit that Krugman has indeed been fairly consistent over the years, though perhaps through luck (I’ll explain that in a second). A while ago he made a post where he said words to the effect, “I am only in favor of government deficits when we’re in a liquidity trap. In normal times, we just rely on the Fed to cut interest rates and boost aggregate demand that way. I haven’t changed my tune at all.” Both Bob Wenzel and I were surprised by Krugman’s claims. I did some digging, and I have to admit that I could find no smoking gun. In fact, in this article Krugman actually ridicules Dick Cheney for believing in vulgar Keynesian demand management. (!!) Now having admitted that, I think we can really only fail to convict Krugman, as opposed to declaring him innocent. After all, the beef against Krugman is that he’s partisan. So the fact that he was using “standard” economics to blow up Dick Cheney’s call for a tax cut is hardly surprising. A real test would be when a liberal Democrat were in the White House and wanted to increase government spending, while Republicans in Congress wanted to cut it, at a time when the federal funds rate was, say, 4 percent while the unemployment rate was 7 percent. Would Krugman in that scenario agree that the feds should slash the budget but have the drop in AD be offset by expansionary monetary policy? I still have a hard time visualizing that.

* David Kramer plays a great speech from Sir Thomas More that is obviously relevant to our times (and to the asteroid-hating economists amongst us):

On Pacifism (part III of III)

[This was an article I originally wrote for LewRockwell.com in grad school.]

In two previous articles (here and here), I described my evolving opinion of pacifism. Since my childhood (and no doubt due to my Roman Catholic upbringing), I had always viewed pacifists as courageous people, but thought that their philosophy was hopelessly naïve. But lately, the more I think about it, the more I believe that pacifism works. I tried to explain this conversion in my previous articles. I’d like to take this final installment to address some lingering issues (many of which came up in discussion of the first two columns).

Now, before I get going, a disclaimer: In this article, I am going to talk about what “the pacifist” would do or say in a certain situation. That doesn’t mean I necessarily endorse his actions, nor does it mean that I myself would behave as the pacifist. (For example, if someone were attacking my younger brother, I would probably use violence to assist him if I saw no alternative.) My point with these articles has never been to lecture the reader on the morality of pacifism, but merely to show that an individual pacifist or society of pacifists could get along just fine. I am not arguing (here) that the virtuous person must become a pacifist. (Hopefully this caveat will forestall those emailers who politely informed me that I am “the lowest form of evil.”) All I am arguing is that the standard dismissal of pacifism as “impractical” is not as obvious as it first seems.

Terminology

At this point, some distinctions are in order. I define a pacifist as someone who refuses to engage in violence. In arguments over my original articles, I realized that many people thought the “true pacifist” had to basically roll over and die at the hands of evildoers. But this doesn’t follow at all. Although actual pacifists (such as Jesus) believed that you should love your enemies, strictly speaking the pacifist as such need only refrain from using violence against his enemies; he is perfectly free to resist and/or avoid them in any nonviolent way.

This definition of pacifism requires a precise concept of violence, in order to know exactly what sorts of actions are permitted. Although actual pacifists may disagree with me, I believe there is an important difference between force and violence. I take force to mean the application of physical pressure, while violence is force that causes bodily harm. And to relate to the libertarian reader, I can make another distinction and classify violent acts that violate property rights as aggression.

(In this framework, then, armwrestlers would use force against each other, professional boxers would engage in violence against each other, and barfighters would engage in aggression against each other.)

The significance of these distinctions is that it allows pacifist police agencies to use force against suspects. For example, suppose we have a community committed to pacifism. Nonetheless, a certain individual finds this philosophy absurd, and holds up a convenience store. As I have defined pacifism, it would be perfectly consistent for police to respond to the scene. Although they couldn’t carry conventional weapons, they could still protect themselves with body armor. Moreover (and more controversially), I am claiming that they could use nets, foam spray guns, or other devices to restrain the suspect, or could even form a human shield (perhaps with bulletproof sheets of glass) to bring him into custody. The point is, I am claiming that a police department could get by without ever inflicting actual harm on anyone, that is, without ever using violence.

True Pacifism?

A few of my critics claimed that what I am advocating isn’t “true” pacifism. To the extent that my position differs from that of typical pacifists (who might, e.g., not condone the existence of a police force at all), then I agree. Were I writing for something other than the Internet, perhaps I’d use a more accurate term for this philosophy of life, such as nonviolence.

But before leaving this issue, I want to point out a certain inequity. One of the techniques that my critics used to point out that I personally wasn’t a “true pacifist” was to ask, “Suppose your wife were going to be raped. Would you still refuse to use violence?” To this, I had to admit that I would not.

But why does this disqualify one from being a pacifist? If someone claims to be a vegetarian, i.e. one who refuses to eat meat, it is common for skeptics to ask, “What about eggs? Would you eat fish?” But I’ve never heard anyone say, “Suppose someone were going to rape your wife unless you ate a burger. Would you still be a vegetarian?”

In fact, it is only because historically there have been many pacifists who were just that committed in their refusal, that we hold “true pacifism” to such a higher standard than “true vegetarianism” or even “true libertarianism.” (On the last point, I asked my critic—a self-professed anarchist—if he would rather allow the existence of government than allow his wife to be raped. He answered yes, and so I pointed out that he’s therefore not really a “true anarchist.”) The fact that many people have been willing to die rather than use violence shouldn’t somehow discredit pacifism; it should rather strengthen it.

Now, there is a sense in which my critic’s question was more legitimate than if he’d used the same technique against a professed vegetarian. Most people generally condemn the use of violence, except in certain situations. Therefore, if one is going to call himself a pacifist, the critic wants to know exactly how his stance differs from the typical one.

I would answer that the pacifist is one who views violence as unsavory per se. If you like, we can say that the types of cases in which such a person would actually use violence would be a gauge of the “purity” of his pacifism. But I don’t think it’s helpful to merely divide the world into “those who wouldn’t use violence to prevent the rape of a spouse” and “those who would.”

To illustrate: Libertarians agree that it is immoral to initiate aggression. But the pacifistic person would say that this principle, though valid, is too permissive of defensive force. He would not, for example, shoot someone for breaking into his car. The extremely pure pacifist wouldn’t even punch an attacker to avoid a vicious beating. And of course the purest of pacifists (many of whom have actually lived and died) wouldn’t use violence even to save their lives.

Gun Control

For some reason, many people who read my original articles thought that the pacifist must advocate gun control. But this is quite false. The pacifist believes that violence is an unacceptable tool to achieve one’s ends. And so, even though the pacifist would prefer a world without guns, he cannot condone the use of violent gangs of government employees to (attempt to) bring about such a world.

Private Defense

Some of my readers were puzzled that I had defended pacifism, shortly after writing a pamphlet that discussed the advantages of private (versus government) military defense. But this is similar to the confusion over gun control: In order for the government to engage in “national defense,” it must use (the threat of) violence to keep out competitors, and to extort revenues from taxpayers. So the pacifist must obviously object to government defense.

Now, as a value-neutral economist, I can predict that in the absence of government militaries (and prohibitions on private counterparts), the free market would provide efficient defense services to (non-pacifist) customers. This involves no contradiction on my part. I can advocate the legalization of crack cocaine, while at the same time preach that consumption of such a drug is immoral and counterproductive to one’s “true” aims in life.

Moral Reprobates?

Some people accept that pacifism is a viable strategy, but only if the pacifist relies on the (defensive) violence provided by others. I argued in my first two articles that this claim isn’t true; I claimed that pacifism becomes more practical the more people who adopt it.

In this article, I want to add that I see nothing hypocritical about a pacifist taking advantage of the current situation. For example, I claimed (in on-line debates) that a pacifist could reduce the chance of muggings by living near police departments. Critics objected that this was pure hypocrisy.

But why is this so? Suppose a pacifist is being chased by a mugger who can’t swim. Is the pacifist allowed to jump in a lake, knowing that his predator dare not follow? If so, then why can’t the pacifist run to the nearest police department, knowing his mugger dare not follow? So long as the pacifist believes that the police officers ought to resign, I see no reason he has to ignore the fact that, in the present world, police officers do not share his opinions on nonviolence.

I must say that I was surprised at the disgust with which some people met my original articles. As I said in the beginning, I had always respected pacifists; I just thought they were naïve. This clash is illustrated by an exchange I had with one of my on-line critics:

Critic: Someone asked Tolstoy [a pacifist] if he would use force to stop a drunk from kicking a child to death. He thought about it for a while and then answered, “No.” But, what kind of person wouldn’t use force to stop a drunk from kicking a child to death? [bold original]

Murphy: Simple: The kind of person who writes War and Peace and The Kingdom of God is Within You. Now that I’ve answered your question, are you still so sure the pacifist is a coward…or a moral degenerate?

And of course, those who embrace pacifism on religious grounds certainly shouldn’t be accused of moral degeneracy. After all, God Himself allows evil things to happen.

Conclusion

My reflections on pacifism have led me to reverse my childhood opinion. There is no reason that a society of pacifists couldn’t function. Even if they were occasionally prone to invasions, their superior technology and economy would allow them to ultimately outbreed rival cultures.

As I have stressed in each of these articles, I am not claiming that pacifism is the only way to live. I am claiming that it is an entirely practical option. The power of violence is greatly overrated. Pacifism works.

On Pacifism (part II of III)

[This was an article I originally wrote for LewRockwell.com in grad school.]

In my last article I shared my thoughts on pacifism. Judging by the response I received—one longtime reader told me it was the worst article he had ever seen by me—I thought a second essay was in order.

First of all, my main point was not to lecture everyone on the sins of violent behavior. I realize I may have come off like that, but it was truly not my intent. Rather, all I was trying to show was that the ostensible “noble but naïve” doctrine of pacifism was not so impractical, after all. I argued that pacifism, the refusal to engage in violence for any reason, was an effective approach to social affairs. Although many actual pacifists adopt their stance for religious reasons, this was certainly not the argument I was making.

Second, I was not using a game theoretic model—in which I viewed people as agents choosing whether to be Hawks, Doves, or Snapping Turtles—in order to “prove” the case for pacifism. On the contrary, I was showing the limitations of such an analysis. A typical objection to pacifism is that it could not serve as a universal code of conduct; if everyone were a pacifist, so the thinking goes, then a few strong individuals would easily exploit such a population of Doves. Thus it is only “natural” for Hawks and Snapping Turtles to evolve, until the point when an equilibrium is reached, and individuals on the margin are indifferent between a life of violence or a life of pacifism.

Again, I objected to this game theoretic treatment, on the grounds that one of its conclusions is empirically falsified. I argued that the Doves of this world earn much greater lifetime “payoffs” than Hawks or even Snapping Turtles. For normal people, this is evident in the greater life expectancy of people who lead peaceful lives, and eschew all conflict. For extraordinary people, this advantage is demonstrated by the superior influence of pacifists such as Jesus and Gandhi versus aggressors such as Hitler and Stalin. Because of this empirical evidence, I argued, the standard game theoretic analysis—and hence refutation—of pacifism was thrown into doubt.

* * *

Now for some more interesting objections: One guy told me I was a hypocrite, because everyday my immune system engages in “warfare” with deadly microbes. Just as I repel micro invaders with “violence,” he claimed, it is only natural to treat macro invaders (i.e. aggressive humans) the same way. Well, all I can say is that by pacifism I mean the refusal to engage in violence against fellow human beings. If you want to come up with a more specific term (that explicitly allows “violence” against parasites and, I suppose, allows violence against farm animals) be my guest.

A related objection was that a society of Doves is clearly unnatural, since we do not see this in the animal kingdom. In other words, if I’m right, how come there are still predators and prey? I think this objection takes the terms Hawk and Dove too literally. There is a qualitative difference in the cognitive and communication abilities among human beings versus other animals, which makes the strategy of pacifism far more effective for homo sapiens. After all, a communist could just as well argue that money is clearly “unnatural,” since other animals manage to feed their young without its use.

Another popular criticism of my last article was that the examples of Jesus and Gandhi were far from typical. (No kidding.) My critics claimed that Gandhi and Martin Luther King were only able to achieve their political objectives with nonviolent civil disobedience because they lived in democratic societies. [Correction: The critic meant that Gandhi was appealing to the conscience of democratic Brits.] Had such people lived under Stalin, their weak defiance would have met with instant death, and no one today would know their names.

This may be perfectly true, but so what? All the critics have shown is that pacifist activists will sometimes meet with failure. The critics did not show that violent resistance would have been more prudent in the Soviet Union. Indeed, the absolute worst thing to do in a repressive regime is take up arms against the government, unless one is assured of military victory. No, the prudent thing to do is to follow the example of Ludwig von Mises when he was threatened by the Nazis: run like a gazelle. (Mises and his wife fled Europe and immigrated to the United States, where he led a productive career advancing the cause of liberty.)

I find this alleged counterexample of the Soviet Union to actually strengthen my case. How was the Evil Empire actually brought down? Was it through violent insurrection? Or was it through a gradual (and peaceful) erosion of the ideological support for the communist regime? Opinions will differ, and no doubt many angry readers will email me and claim, e.g., that without a hawkish U.S. foreign policy, the Soviets would have taken over the world. Even so, in the end it was not Air Force bombers, but the Russian people who had finally had enough, that spelled the end of the U.S.S.R.

The best objection I received concerned the truly nightmarish scenarios when (defensive) violence seems to be absolutely necessary. To be blunt, many people wanted to know if I were advocating pacifism in the face of someone raping a daughter or beating a child.

Of course one shies away from even thinking of such cases, but they are an unfortunate fact of life. But let’s be logical about it: Most rapists (or child abusers or kidnappers) do not perform their dastardly deeds in front of the victims’ parents, or anyone else for that matter. And those that do—for example soldiers in Bosnia or other areas suffering civil war—are heavily armed, and the parents can’t do anything about it, anyway.

Whether or not you as a parent own a gun and are prepared to kill to defend your family, the very best thing (it seems to me) you can do to protect your children is to teach them to use their head in order to avoid such situations in the first place. Instructing children to avoid strangers, stay in groups, learn to identify suspicious behavior, etc. is far more important than keeping a gun in the house, for the simple fact that all of the awful scenarios described above will probably not happen in the household, but out in public.

But what about the home intruder? Isn’t a gun necessary to repel him? No, not necessary. Pacifist families can move to rural areas where crime is nonexistent. If that is impractical, they can have alarm systems, watchdogs, and “panic rooms” installed. Plenty of households currently manage to get along without guns.

(To forestall any hostile emailers: Please, for those of you who own gun(s) and feel very strongly about it, I am not saying you are immoral or endangering your family. I am merely pointing out that the pacifist lifestyle doesn’t leave one nearly as vulnerable as it first appears.)

* * *

The above reasoning may strike some readers as a bit odd. Yes, they may say, pacifists can get along in the modern world. But that’s only because people are rarely called upon to use defensive violence. And in those rare cases—such as being stuck on an airplane with hijackers, or on a train with a crazed gunman—it is certainly better to be armed and willing to kill. After all, the Snapping Turtle acts like a Dove most of the time, except when he needs to use violence to defend himself.

I believe that this argument leaves something out: the corrupting effects of violence. Even before I had adopted my current stance, I decided I would never carry a gun on me. I have lived in some fairly sketchy neighborhoods in my day, but nonetheless decided that it would be safer for me to remain unarmed.

Why? Because I knew that carrying a gun would give me a heightened sense of security and confidence. There have been days when I, in a particularly pissy mood, have walked around dangerous areas almost hoping someone would mess with me, so I could (with justification) fight the guy.

Don’t misunderstand me: There’s no way I would ever have shot someone who wasn’t immediately threatening my life. But the point is, having a gun would have made me more likely to encounter such situations in the first place. When I lived in Crown Heights, for example, the young punks there would often swear at me, spit in my general direction, and even (on one occasion) threaten to shoot me. At the time, I simply ignored the affronts, or otherwise defused the situation as quickly as possible. But if I’d had a gun, I may have “stood up for myself,” and ended up shooting somebody.

Now here’s the point: It’s not so much that I would have felt bad for killing somebody; like I said, I wouldn’t shoot anybody unless he were threatening my life first. But nonetheless, I would have had to move immediately. For the rest of my life, I would have worried that the deceased’s family or friends might hunt me down. And of course, no matter how “justified” the shooting may have been, I probably wouldn’t go a day without second guessing my actions.

So for these reasons, I decided I would never carry a gun. Now I’ve come to realize that this reasoning holds for the use of violence in general. Simply put, if you promise yourself that you will never, under any circumstances, cause injury to another human being, then that stance forces you to reevaluate your lifestyle. You choose which routes you walk home more carefully, you choose not to go to certain neighborhoods, you don’t go to a poker party if you know your buddy cheats people, etc. And, I would venture, in the long run it’s just possible that taking away the option of violence makes you safer.

(For the skeptics out there: You needn’t adopt full-blown pacifism to see my point. Perhaps a simpler step would be to promise oneself never to kill another person, or never to use violence unless one’s life were in immediate danger. Thus, shooting a thief as he runs away would be unacceptable.)

We see that pacifism is not nearly as crippling as the critics would have us believe. In fact, precisely because it is so underrated, its practitioners enjoy a tremendous advantageous when they interact with “normal” people. This is why Gandhi and others like him wielded such tremendous moral authority.

* * *

The above has demonstrated that pacifism can work on an individual level. That is, I have argued that someone who immediately switched from Snapping Turtle to Dove in the game of life would do much better for himself.

But doesn’t this philosophy lack integrity? After all, the only reason pacifists currently avoid domination is their protection from others who are willing to use violence. Without police and armies, the argument goes, pacifists living in prosperous regions would soon realize the weakness of their approach.

I believe this argument is incorrect. As I explained in my previous article, surely pacifism can only become more practical as greater numbers adopt it. That is, as more and more people became Doves, the world would become a less violent place. It would seem less and less foolish to become a Dove and (supposedly) leave oneself at the mercy of Hawks, because fewer Hawks would be around. As more and more individuals unilaterally “disarmed,” the cycle of violence (a trite but accurate expression) would be reversed, and pacifism would no longer seem to be “for suckers” as it is now. Every succeeding generation would see less and less violence first hand, and thus would be less likely to find it normal and “acceptable.”

“But what if everyone became a pacifist??” the critic demands. I respond that that would be wonderful! In such a world, there would be no governments at all (since government relies on an initiation of force to collect taxes). There would be no need for armies or weapons. Such a world would enjoy prosperity and tranquility that almost defies modern comprehension.

But why wouldn’t new Hawks emerge in such a world, to dominate the weak and establish a new government? Simple: a group of Hawks would be unable to do this. Without the ideological support for government given voluntarily by the masses, no government is sustainable.

And what of common thieves? Well, there are plenty of “defensive” measures that people can take, short of violence. Houses could still be locked, banks would still have safes, and police (unarmed, of course) could still track criminals. An extensive rating system could be developed, to notify areas when violent people entered their midst. Economic sanctions and other nonviolent responses could be used to punish violent offenders and thus deter their behavior.

* * *

I hope the above has demonstrated that, contrary to popular belief, pacifism is a practical lifestyle, and only becomes more so as more and more people embrace it. It is true, a world of pacifists would occasionally endure theft, rape, and murder at the hands of evil and sadistic individuals. But this happens in the present world, too. I am not claiming a pacifist world would be perfect, merely that it would be better than the current one.

Finally, let me reiterate that I am not claiming any flaws in the standard libertarian position, which claims that defensive force is justified. All I have shown is that a rival philosophy—that of pacifism—is internally consistent and also pragmatic. (In a sense, pacifism is like vegetarianism: You may think it a sissy lifestyle choice that’s not for you, but you can’t prove that those who adopt it—whether for moral or simply health reasons—are in any way making a “mistake.”)

The power of violence is greatly overrated. Pacifism works.

On Pacifism (part I of III)

[This was an article I originally wrote for LewRockwell.com in grad school.]

I have always been fascinated by pacifism. We all know that if everybody refrained from violence, we would all be much, much better off. But pacifists go further and say that even if other people are going around stealing and killing, you will still always be happiest (or most successful in whatever way you define success) if you renounce the use of violence. I enjoy bold conjectures in general, and in particular ones about society; and there is nothing bolder than the theory of the pacifists.

Yet, although fascinated by pacifism, I could never fully accept its conclusions. I knew that pacifism was where I was “headed,” that it represented the logical fruition of my intellectual development. I had started out by studying free-market economics, then became slowly convinced that the government shouldn’t do much of anything, and finally started thinking the government shouldn’t exist.

But if you step back and look at it, I was really just limiting the scope of acceptable uses of violence. In the first stage, I realized that it’s counterproductive to use men with guns to threaten people into paying unskilled workers a certain minimum for their labor. In the second, I realized that it’s even counterproductive to use men with guns to collect money from everyone in order to pay companies to build fleets and nuclear bombs. And in the last step, my acceptance of full-blown anarchy, I realized that there’s no need for an institution of organized violence (i.e. government) at all; we can get along just fine without one, thank you.

These political (or anti-political) views could be subsumed by the ethical doctrine of (radical) libertarianism. The non-aggression axiom ruled out the initiation of force, and oops! there goes the State. But it went further and proscribed a whole class of actions in one’s private life, too. The non-aggression axiom forbade the institutional theft of taxation, yes, but it also ruled out theft on an individual scale.

However, even radical libertarianism allows for the use of defensive force. But not pacifists. Even if someone is punching and kicking you, the true pacifist says, you should just sit there and take it (or perhaps run away if you can). But never are you justified in injuring (or even threatening to do so) your attacker to get him to stop.

Now, most people probably respect the courage of the true pacifist, but nonetheless think that he’s being naïve. Most people would argue that cold hard reality makes (at least the threat of) defensive force necessary.

* * *

This is actually one of those situations that could benefit from formal analysis. So with apologies to any Austrian economists who may be reading, I’m going to look at this from a typical game theorist’s point of view:

Let’s suppose the world is populated by agents who can pick one of three “strategies”: Hawk, Dove, and Snapping Turtle. If you’re a Hawk, you spend your time enhancing your strength, and you use your power to intimidate those weaker than you. If you’re a Dove, you are completely helpless in the event of an attack, and so you spend your days building alliances and learning how to avoid conflict. Finally, if you’re a Snapping Turtle, you spend all your time preparing for your retaliation against any attack.

Now, to figure out what the “optimal” strategy is, we need to know how these agents interact with each other. If Dove meets up with another Dove or Snapping Turtle, they engage in peaceful cooperation and gain some utility. If Hawk runs into Dove, Hawk gets a lot of utility and Dove loses a little. If Hawk runs into Snapping Turtle, the stronger Hawk gains just a little utility (since even a successful mugging is stressful if the victim resists) while Snapping Turtle loses a moderate amount. Finally, if two Hawks run into each other they both lose a tremendous amount of utility.

Now if we chose “reasonable” numbers to plug into a model along these lines, we would find that a society of Doves is unstable. In a world of Doves, any individual could defect and become a Hawk, and thereby take whatever he wanted from anyone he met. Since there were only Doves around, he would never be punished for this aggression. Therefore (the standard game theorist would argue) pacifism as a universal code of conduct is impractical.

(Incidentally, I point out that even in this standard setup, the libertarians could defend their view. Given appropriate numbers, it is entirely possible that the unique equilibrium occurs when everyone is a Snapping Turtle. Anyone who turned into a Hawk in such a world would instantly lose out on the large benefits from cooperation with all his neighbors, and every one of his encounters would be a battle against a foe who resisted.)

The implication one draws from this analysis is that the present society—with its mixture of Hawks, Doves, and Snapping Turtles—is in equilibrium, that on the margin there are individuals who are indifferent between the various strategies. Even if we believe that childhood rearing and other social forces limit the discretion over the lifestyle “strategy” one chooses, nonetheless we would expect (so says the typical game theorist) the success of the various populations of Hawks, Doves, and Snapping Turtles to compensate for this lack of choice on the individual level. Simply put, there aren’t more Doves because too many of them die at the hands of aggressors. And there aren’t more Hawks because too many of them are killed out of fear or vengeance, often by subordinates who despise them.

* * *

But does this really stand up to scrutiny? Is it really the case that a child destined to be a peacemaker is expected to have the same fortunes in life as a child destined to be a bully?

To ask the question is to answer it. In purely “material” terms, the Doves of the world earn much higher “returns” than anyone else. Just because you are a Dove doesn’t mean you need to advertise the fact, and so Doves are no more attractive to a mugger than a Snapping Turtle. And during the course of a mugging, the “safest” strategy we can recommend ex ante is to give the guy your money.

The reason many people would resist the mugger is to uphold the principle of the matter; but these are not monetary considerations. And the standard objection against pacifism is that it’s idealistic. Well, what’s more pragmatic than recommending losing face in order to stay alive? All of the “glamorous” professions of violence—such as politics and drug dealing—have a much lower life expectancy than the “weak” lifestyle of the schoolteacher or priest. In a sense, the person who lives the life of violence takes an incredibly risky gamble, a gamble where the odds are (at least in the modern world) heavily stacked against the player.

Not only does the average pacifist prosper more, but the most “successful” people the human race has ever produced are pacifists. Jesus and Gandhi will have a far greater impact on humanity than Hitler or Stalin. People have said that entire villages would change when Mother Theresa walked through.

Clearly then, the standard game theoretic analysis is leaving something out. And I think one neglected factor is that a true pacifist signals to others his integrity. People aren’t really divisible into three broad types like Hawk or Dove; it would be more accurate to classify them on a spectrum ranging from evil to honorable. And there are certain types of cooperation (e.g. marriage) that can only work if there is a sufficient degree of trust in the character of the other party.

It would thus appear that the pacifists are sitting on one of the best-kept secrets ever discovered.

* * *

It’s rather ironic, when you think about it. The basic idea of pacifism is so simple and intuitive, that skeptical humans reject it as too good to be true. But it clearly “works” if a few implement it, as proved by Gandhi (I leave out Jesus because one could argue that He had an “advantage” since, e.g. He could conquer death). Now surely pacifism can become only more “practical” as greater numbers adopt it. In the limit, if virtually everyone were a pacifist, then a group of totalitarians couldn’t possibly hurt many of them, since the would-be tyrants would have no soldiers to carry out their orders.

In a very literal sense, the peacemakers shall inherit the earth.

Is Coercion Inevitable?

I came across this interesting clip from a Western journalist interviewing a Soviet physicist in the 1960s. The part that caught my attention:

It amuses me when I go abroad for conferences and hear my American colleagues prattle on about the “scientific method.” I don’t doubt their sincerity. They genuinely believe that the “best science” will rise to the top through experiments and an objective weighing of the evidence. They genuinely believe that there could be a physics without politics. But in reality, of course, physics–and all science, regardless of the discipline–is whatever the dominant group says that it is. If some scientists believe Theory A, while others believe Theory B, then there are only three possible outcomes: (1) The proponents of one theory bite their tongues and pretend to believe in the oppose theory, or (2) they forfeit their academic positions or (3) they emigrate to another country where their preferred theory is the dominant one. No other outcome is possible. All science is coercive.

Now, does anybody buy the above view of science? Living as the Soviet physicist did, in a highly politicized world, you can understand why he would utter such nonsense–but clearly it is nonsense.

Well, now you know my reaction to this Gene Callahan post on libertarians and property rights, which my (genuinely) favorite pseudo-Keynesian Daniel Kuehn is swooning over.

I don’t think Gene (and Daniel) are being fair to sophisticated versions of Rothbardian libertarianism; Mattheus von Guttenberg tries to make the case here. But I have a much simpler response: Gene and Daniel don’t even mention the fact that there are real-life pacifists who not only reject explicit violence but also hatred itself. (If you don’t believe me, skim this story.)

If Gene and Daniel were simply making an empirical claim that in practice, a non-coercive society would break down, that would be one thing. But if you read their posts, it sounds like they are saying far more than that. Indeed, they seem to be saying that by its very nature social life requires coercion.

In order to rebut this view, I will re-post some of my old essays on pacifism.

Recent Comments