The Irrational Doubting Thomas

I can’t put my finger on a good example right now, but over the years I have come across atheists/agnostics who praise “Doubting Thomas,” the apostle who demanded proof when the other apostles said they had seen the resurrected Jesus. To refresh our memories (John 20: 19-29):

19 Then, the same day at evening, being the first day of the week, when the doors were shut where the disciples were assembled, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood in the midst, and said to them, “Peace be with you.” 20 When He had said this, He showed them His hands and His side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.

21 So Jesus said to them again, “Peace to you! As the Father has sent Me, I also send you.” 22 And when He had said this, He breathed on them, and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. 23 If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

24 Now Thomas, called the Twin, one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came. 25 The other disciples therefore said to him, “We have seen the Lord.”

So he said to them, “Unless I see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and put my hand into His side, I will not believe.”

26 And after eight days His disciples were again inside, and Thomas with them. Jesus came, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst, and said, “Peace to you!” 27 Then He said to Thomas, “Reach your finger here, and look at My hands; and reach your hand here, and put it into My side. Do not be unbelieving, but believing.”

28 And Thomas answered and said to Him, “My Lord and my God!”

29 Jesus said to him, “Thomas, because you have seen Me, you have believed. Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

To repeat, unfortunately I can’t point to any quotes as examples, but many times I have seen skeptics saying that “Doubting Thomas” is being quite rational and scientific, because “everybody knows” that somebody can’t come back from the dead.

Yet I want to argue that Thomas is being quite irrational and anti-empirical. In the context of the gospel accounts, he has seen (or heard about) Jesus performing countless miracles. These included feeding thousands of people from a few loaves of bread, healing the blind, healing the paralyzed, healing lepers, and walking on water.

Moreover, Jesus had raised others from the dead, before His own death. Most famously He brought Lazarus back from the dead, after he had been in the tomb for four days–even those who trusted Jesus the most were trying to wave Him off, because “obviously” it was too late. But Jesus also raised a young girl from the dead, quite publicly. (I.e. everybody knew she was dead, then Jesus went in and healed her.)

Finally, on different occasions Jesus predicted His own death and resurrection to His apostles, so it should have been perfectly reasonable for Thomas to believe them when they said He had returned.

Now of course, today’s atheists/agnostics will say that the above links are to fairy tales, and that those miracles never happened. OK fair enough; I don’t want to argue that in today’s post. But then it doesn’t make sense to say Doubting Thomas is your role model, because he’s a fairy tale too. It would be like saying you respect Han Solo for not believing in all that mumbo-jumbo about “using the force”; everybody knows you need a good blaster to defend yourself from Storm Troopers.

In conclusion, I am saying that either you take the gospel accounts at face value–either as morality tales containing a great deal of wisdom about living a good life, or as actual historical events–in which case Thomas was (understandably) obstinate in his refusal to accept reality. Or, you can reject the stories as absurd and useless for modern life.

But in no case does it make sense to praise the disbelief of Thomas.

Murphy vs. Fed Economist

This was my debate with Gerald Dwyer, an economist who worked for the Atlanta Fed back in February. I am at a hotel right now for a Mises Circle event so I haven’t been able to watch any of this.

On the off-chance that some new readers haven’t heard about it, I have a campaign to debate Paul Krugman. Make your pledge today!

A Satisfied Customer

I recently got this email from Ryan, reproduced below with permission. I like reading his email a lot more than the comments from David S. on this blog.

Good afternoon Dr. Murphy,

I am currently reading your book (as we speak in fact) Lessons for the Young Economist and am currently on page 42.

Ever since I began reading LewRockwell.com and Mises.org in early 2003 it was, to some extent, difficult to grasp the fundamental concepts that underlies so-called “economic thinking.” As a result, it was extremely difficult, though not impossible, for me to go into greater depth on the subject.

Despite reading literally 6000+ (this is not an exaggeration) LewRockwell.com articles and a couple of thousand articles at Mises.org my mind could not quite grasp the ‘scholarly” articles as well as a great deal of Mises’ work. However, after being just 42 pages into your book it is now becoming very clear. Your ability to provide substantive explanatory power to the reader is extraordinary. Many intelligent individuals are unable to instruct their students due to an inability to speak in terms a non-economist would understand. Clearly your teaching skills are exquisite as well as possessing a brilliant mind.

to conclude, allow me to present to you thanks for your hard work ad dedication to instructing others on the importance of economics as well as teaching subject itself to prospective economics students and layman alike.

a friend in liberty,

RyanP. S. While I have the free PDF and am currently reading it on my computer I also purchased a hardback. The reason for the latter is two-fold. First, the book can be read while being away from the computer. Second, because in my opinion you deserve some form of compensation for the excellent work that is Lessons for the Young Economist.

I explained to Ryan that although I appreciated the gesture, I actually got a lump sum payment for writing the book. So he could stick it to The Man for all I cared.

Update on (Price) Inflation

I know I’m supposed to hang my head in shame at how some of us have been Chicken Littles on price inflation, but I’m still not sure it’s time to throw in the towel. (For the record: Yes I have definitely been wrong in the specific timeframes I gave for when we’d see certain things happening with CPI.)

For example, looking at the latest numbers from the BLS, coming from the Producer Price Index and Consumer Price Index, we get the following 12-month changes:

Consumer goods except food and energy: +1.3%

Consumer goods: +3.2%

Finished goods: +6.8%

Intermediate goods: +9.4%

Crude goods: 23.7%

And in light of all this, I’m supposed to just roll over and say, “Yep there is clearly no sign of price inflation in the system.” ? I don’t mind people saying, “I think this is a one-time blip in commodities that will work its way through the headline numbers,” like so.

But Krugman et al. are going much farther than that, acting as if only Newt Gingrich could be so stupid as to think there is any sign of inflation. Steven Chapman (HT2 David R. Henderson) goes so far as to say, “The last epidemic of inflation, in the 1970s and early ’80s, was a searing experience, from which the Federal Reserve learned lessons it has no desire to repeat. Is inflation coming back? Sure. Right after the Ford Pinto.”

Really? That’s how confident we all are in this guy?

Potpourri

* Silas Barta smells a rat in the official inflation numbers.

* Ha ha, those Austrian economists teach at small schools and have funny names for their dogs. QED.

* I have written in several places that the Fed is responsible (at least in part) for rising commodity prices and oil in particular. Jerry Taylor and Peter van Doren disagree, saying that speculators have nothing to do with oil prices. It can all be explained by fundamentals and elasticities.

* Bob Wenzel linked to this piece on excess government properties.

* William Grigg has been following this disturbing story of a SWAT team barging into a guy’s house and killing him. Apparently they held the medics at bay for an hour while the guy died. Does anyone want to play devil’s advocate and offer some rival interpretation?

* The nightmare is over. And remember, they hate us for our Walkers. (BTW the top comments are better than the article.)

* My article at Mises today talks about privatizing transportation in New York City. I didn’t make this assertion in the piece, but I honestly believe the crime rate would drop significantly over time if they implemented my ideas. A highlight:

As an economist, it appalls me how wasteful the current system is. Every weekday, millions of very productive engineers, doctors, writers, and other workers sit in traffic jams going into and out of Manhattan. Under private ownership, the tolls on bridges and tunnels, and the fees (however allocated) for driving on the normal roads would reflect the actual demand for the scarce product.

There would be time-varying prices, too, so that people who could rearrange their schedules to avoid rush hour could save money and thereby reduce peak congestion. (Such pricing structures have slowly been introduced even by the government’s transportation authorities, but not very quickly.) Yes, the month after a full-scale privatization of all the roads and bridges, it might be very expensive to drive from Wall Street to the Hamptons at 4:45pm on the Friday of a three-day weekend. But at least it could be done in a very smooth fashion, without having to stop-and-go for an hour or more.

Even better, the high prices would only be temporary. Entrepreneurs would see the demand (signaled by the high prices) and would devise new ways of catering to it. After a few years of genuine private ownership in transportation systems, Manhattan would look like a science fiction movie. There would probably be multiple layers of new bridges and tunnels, and extremely clean subway systems that were never too crowded, because of appropriate pricing and customer management. (Do you ever go to a movie theater — even for a popular film on opening night — and have someone try to squeeze into your seat? Of course not: the theater owners don’t allow patrons to crush each other. But that happens all the time with government subways.)

Tom Woods Plugs “Night of Clarity” and Murphy Karaoke

Remember, there is a 10% discount if you sign up for this year’s event by May 15th.

AP Lerner Explains Alleged Crowding Out Chart

Well, if it had turned out the other way, I certainly would have blogged it, so I feel compelled to report that frequent commenter and MMT defender “AP Lerner” poked a big hole in the comments of my previous post.

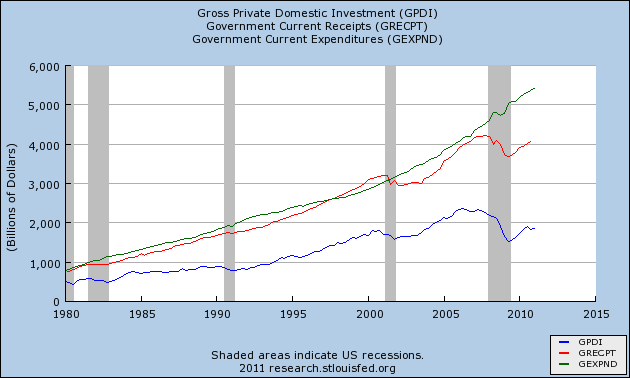

Recall that I had posted a chart showing that Gross Private Domestic Investment tracked the (inverse of the) government budget deficit very closely. So it seemed to support the standard “crowding out” argument, whereby a government deficit siphons off resources from private-sector investment.

AP Lerner thought this was a bogus interpretation of the chart, saying:

If crowding out was occurring today, then why aren’t rates higher? Why is there such demand for corporate AND treasury bonds are oversubscribed by 3x?

All your chart above shows is private sector investment falls when tax revenue falls, which makes perfect sense since tax revenues always fall during a recession.

I looked into his latter claim, and yeah it seems he is right:

To be sure, one doesn’t need to abandon the “crowding out” hypothesis on the basis of the chart above. But AP Lerner is right that the tight correlation between government surpluses and private investment, can in turn be explained by a relatively constant trend of rising government expenditures amidst volatile revenues that are tightly correlated with private investment.

Final Thoughts on MMT

[UPDATE below.]

I kept telling myself that I didn’t have a problem, that I could stop reading the comments in this post whenever I wanted. Well I think I need to go cold turkey. So let me make three main concluding points:

POINT #1: The accounting identities don’t prove the things that the MMTers think they prove, at least not by themselves. They must be supplemented with a particular macroeconomic theory. Rival theories, which yield the opposite conclusions, are just as consistent with the accounting identities.

That was of course the main point of my Mises article, but in the comments at the blog discussion, “MamMoTh” unwittingly illustrated it beautifully. Commenter Eli was arguing with Mammoth, saying that regardless of the government’s behavior, the private sector could save more if it just reduced its consumption.

Mammoth disagreed, saying: “Any individual can adjust his/her saving/consumption ratio. But the whole private sector can reduce consumption, which will reduce income but leave savings unchanged.”

To drive home the point with math, rather than mere words, Mammoth then wrote:

Income:

Y = C+I+GSavings:

S=Y-C-T

=I+(G-T)So consumption does not affect aggregate savings.

But in Eli’s framework, when consumption goes down, investment goes up, and Y stays the same. That is totally consistent with the first equation above. Mammoth looks at Y = C+I+G and thinks a drop in consumption is handled by a drop in Y, but it could just as well be handled by an increase in I.

And so then in the reduced form, where S = I + (G-T), when I goes up, savings can go up on the left hand side to keep the equation balanced.

POINT #2: Neither the Austrians nor the Keynesians deny that the Fed could print whatever amount of money is necessary, in order to avoid a technical default on government bonds. We are saying that it’s possible this would cause large price inflation, and that’s why it’s dangerous for the government to run huge deficits year after year.

In several places, the MMTers took umbrage when I (repeating Krugman) said that they believed “deficits don’t matter.” They came back and said yes government budget deficits do matter, but not because of “solvency” issues, rather because of the purchasing power of the USD.

If that’s really the argument, then we can all shake hands and go home. Krugman acknowledges that in his critique of MMT:

[O]nce we’re no longer in a liquidity trap, running large deficits without access to bond markets is a recipe for very high inflation, perhaps even hyperinflation. And no amount of talk about actual financial flows, about who buys what from whom, can make that point disappear: if you’re going to finance deficits by creating monetary base, someone has to be persuaded to hold the additional base.

If you don’t believe me, I encourage you to go back and re-read his post. Krugman isn’t saying, “Deficits eventually matter, once we get out of the liquidity trap, because Uncle Sam might default if he gets in over his head.” No, Krugman specifically concedes that the Fed could just monetize all the debt. His point is, that could lead to runaway price inflation.

Now maybe Krugman is wrong for thinking that, but you don’t advance the argument by saying, “A government issuing its own currency can’t go insolvent.” Nobody is denying that.

POINT #3: Even in its textbook version, “crowding out” is consistent with higher private sector saving. What is being crowded out is private investment.

In a completely unrealistic, everybody-is-a-rational-robot Chicago School model, when the government [UPDATE: A few minor edits because it matters whether the government deficit is due to a tax cut versus a spending increase…] doesn’t raise taxes and yet increases deficit spending maintains its current spending level but gives a deficit-financed lump sum tax rebate, that will cause taxpayers to save more, in order to pay for the higher taxes down the road needed to finance the additional debt. OK, so MMTers aren’t at all scoring points against the “crowding out” hypothesis by showing that private sector savings rates went down during the Clinton surplus years, and up during our recent period of massive government deficits.

Now if we relax the perfect Ricardian equivalence, a more real-world scenario in which “crowding out” occurs, goes like this: The government runs a deficit and thus increases the demand for loanable funds. This pushes up interest rates higher than they otherwise would be. People expect higher taxes, and so they save more, which partially offsets the interest rate hike. However, the effect isn’t perfect, and on net interest rates are higher than they otherwise would be. Therefore private business invests less. In effect, the government has diverted some of the private sector savings that would have gone into private investment, and instead it is being spent as G, not I.

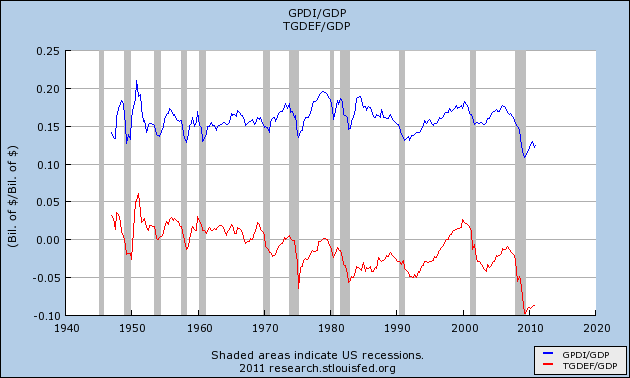

The data are totally consistent with that interpretation. The following chart shows Gross Private Domestic Investment as a share of GDP (top line), versus “net government saving” as a share of GDP (bottom line). Note how they move in close tandem. When the government deficit shrinks, private sector investment goes up. When the government deficit balloons, private sector investment collapses.

So look, I can use the same sectoral balance equations, and I can point to empirical data going back decades, which incorporates periods of government surpluses and massive deficits. The MMT crowd should stop thinking they have a monopoly on accounting truisms and historical evidence.

Recent Comments