Murphy Is a Jersey Boy This Weekend

I am doing an IBC Seminar (with Carlos Lara and Nelson Nash) this Saturday in Morristown, NJ. Details are here.

In the Long Run, I Will Always Quibble With Krugman

Although Steve Landsburg is trying to talk me down from the ledge, I think there’s something rotten in economics. (Maybe this is true in every field and I just notice it here because it’s my area; I’m open to the possibility that “humans are disappointing.”)

For example, DeLong and Krugman have accused Mankiw of not simply choosing poor assumptions, but also of committing a basic math mistake. When several people said “no he didn’t,” DeLong tried to get out of by saying (see his tweets down the list here) that a “static analysis” of tax considerations means you allow behavior and hence the tax base to change. (!)

But back to the main point of the present post: In this intriguing post (and I don’t say that sarcastically), Krugman makes a neat argument to end up concluding that it could take “decades” for the U.S. rate of return on capital to be restored to the world’s average rate, following a cut in the U.S. corporate income tax rate. If true, you can see why Krugman (and DeLong and Summers etc.) are flipping out at the simple models from Mankiw et al., which take the baseline assumption that the U.S. is a small open economy and that international capital mobility is perfect.

However, I think there is a huge problem in Krugman’s analysis. To point it out, I think it’s easiest for me to recapitulate his argument:

(1) The baseline is Harberger, who famously showed that if we have a closed economy with a fixed stock of capital goods, then it is the capitalists who bear 100% of capital taxes.

(2) However, nowadays capital is very mobile internationally. In the limit, if we imagine a small open economy, then the after-tax rate of return to capital in that country must be equal to the world average. If the government of this small economy cuts its corporate income tax, that temporarily means a higher after-tax rate of return in this country, compared to the global average. But then capital from foreign investors flows in, pushing down the PRE-tax return on capital in this small economy, until the after-tax rate of return is once again equal to the world average. So this means the capitalists of this economy don’t benefit from a cut in the corporate income tax. Instead, the *workers* do, because the extra capital flowing in yields more investment, so the higher capital per worker means labor is more productive and hence wage rates are higher.

(3) Krugman says this isn’t the full story. What other people have long known is that you have to worry about monopoly rents, and the fact that the US is a huge economy and so capital flowing into it might raise “the” global rate of return. So even in the new equilibrium, when the after-tax rate of return in the U.S. is the same as for the rest of the world, it might still be that U.S. capitalists (and global investors too) are better off, while U.S. workers have not benefited as much as the analysis in (2) would have supposed.

(4) But, says Krugman, there is another element to all of this, that only Krugman has put his finger on. Specifically, you have to ask what is the mechanism by which a “temporarily” higher after-tax rate of return in the U.S. will be whittled away? Sure, you can say “an inflow of capital from abroad,” but in practice that means the USD appreciates against other currencies, in order to cause a current account deficit (flipside of a capital account surplus). Because only a small portion of GDP is in tradable goods, it means the dollar has to strengthen a LOT to get a really big movement in the trade deficit. Krugman uses some plausible numbers and a Cobb-Douglas production function to estimate “about 6 percent of the deviation from the long run eliminated each year. That’s pretty slow: it will take a dozen years to achieve even half the adjustment to the long run.”

====> OK now that I’ve summarized Krugman’s post, here’s my problem: Krugman is assuming that ALL of the growth in the U.S. capital stock (which is needed to push down U.S. pre-tax “r” such that after-tax U.S. “r” once again equals the global average) must come from an influx of foreign saving. In other words, Krugman assumes that the increased investment in the U.S. must work through a capital account surplus, which is limited (as he says) because of the sluggishness of the international flow of goods.

But that wouldn’t be the only mechanism of adjustment. Apparently Harberger’s baseline result assumed a fixed domestic stock of capital, but of course that’s not true in reality. If the U.S. government cuts the corporate income tax rate, that will increase the return to saving and so American “S” will jump up. So the rate of U.S. capital accumulation will increase, not simply because of an influx of foreign capital, but because Americans will save a higher fraction of their income as well.

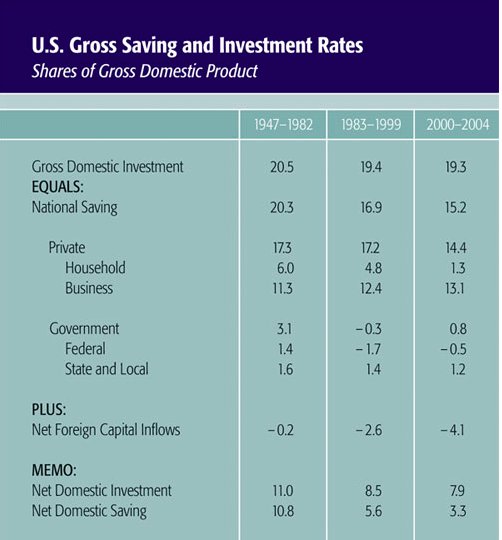

Is this empirically relevant? Well I was googling around and found this from the St. Louis Fed:

So if I’m interpreting those figures correctly, it used to be the case that U.S. saving accounted for almost all of U.S. investment. But more recently (i.e. from 2000-2004), Americans provided about 78% of the saving to finance American investment, while foreigners provided the other 22%. (Gross domestic investment was 19.3% of GDP during this period, while Americans’ saving was 15.2% of GDP and net foreign capital inflows was 4.1% of GDP.)

I think Krugman is telling us that if we have to boost the U.S. capital stock *solely* through the mechanism of larger net inflows of foreign capital, that it could take decades to fully adjust to a corporate income tax cut. OK fine. But at least for the above period, American saving provided 3x the funds for domestic investment. Those figures might have moved a lot because of government deficits but surely we shouldn’t ignore the role of American saving?

Murphy’s “History of Economic Thought Part II” Now Available on Liberty Classroom

Hey boys and girls, the second installment of my course on the History of Economic Thought is now available at Tom Woods’ Liberty Classroom. This second installment is a tour of 20th century thought, covering the following topics:

As the list indicates, some of these topics can get a bit technical. I’d like to think that I struck a good balance, providing the intuitive overview of important concepts (such as the “Lucas critique”) for the layperson, while also giving some of the technical details for grad students and/or other economists who may not have studied some of these areas.

My goal in these lectures is to get the student to pass a Turing test for the material in question. For example, I don’t spend much time at all criticizing Keynes; instead I try to interpret what he’s doing in the sections that I chose to highlight from his book. (I also point out that his infamous “in the long run we’re all dead” was NOT a justification for deficit finance.)

I spend a lot of time on capital and interest theory, since that is my specialty, and I hope I convince the student why the Austrian insights here are so crucial. But I also spend a lot of time on game theory, since I think there is a lot of confusion even among mainstream economists on things like a “mixed-strategy equilibrium.”

The last plug I’ll give is this: After I uploaded the last video, I was much more relaxed when considering the prospect of being hit by a bus. I thought, “I have done my part for humanity by distilling a lot of my knowledge of economics into this 2-part History of Thought course. If I die tomorrow, so be it.”

So go sign yourself up for Tom Woods’ Liberty Classroom.

Two Pacifists Fight on Twitter

I screenshotted (screenshot?) it because I think the embed feature would screw up the order, but this was a pretty big gulf in our worldviews:

Confused by the Confusion

I’ve been busy with traveling (including the super duper awesome Contra Cruise II), and so I am just now catching up on all of the controversy surrounding the economics of a corporate income tax cut. As you can imagine, some conservative/libertarian economists said good things about it, and then DeLong and Krugman pointed out that the assumptions used in these blog posts were false, and furthermore said (quite explicitly) that only their hackery could have led such smart economists to say such stupid things.

But beyond that stuff (which goes without saying), there is something else weird going on here. After Steve Landsburg tried to give the intuition for a result that surprised Mankiw (when he–Mankiw–derived it), I wrote in the comments to Steve’s post:

Steve,

I’m a little bit confused by all of this. And I *don’t* mean by the competing/complementary blog posts, rather, I mean that leading economists seem like they’ve just been presented with the notion of a corporate tax cut for the first time 3 weeks ago. How is it that big shots are arguing over something so basic?

I feel like one of the bestselling textbook physicists just wrote a post saying, “Wow, it turns out, under certain assumptions (such as no air friction), that the mass of an object has nothing to do with its acceleration near the earth’s surface!”

Then another physicist chimes in on his blog, “I spent all morning trying to understand this result, but I think I see it now…”

I hope you understand, I’m not criticizing you or Mankiw. *I* hadn’t thought of any of this stuff before. But am I missing something? How can it be that the economics profession is grappling with the notion of, “How should we even conceptualize a corporate income tax cut?”

I really think mainstream economists are fooling themselves when they imagine that they are sitting atop a body of solid empirical knowledge. Look: Two teams of economists can look at LITERALLY THE SAME RECENT DATA regarding Seattle’s minimum wage, yet reach opposite conclusions–and neither team is lying!

Imagine President Trump said he wanted to send a man to Mars. And then leading rocket engineers started arguing on their blogs about whether you should point the rocket toward Mars or away from it. That is almost where we are, when it comes to economists arguing about the corporate tax right now.

Sure, you can say, “Oh it’s all political,” but the rocket scientists trying to get funding for their plan wouldn’t be able to say rocket thrust goes in the wrong direction.

All of this tells me that Ludwig von Mises was right when he argued that economic science is a logical, deductive science, and that aping physics was foolish.

Once you get to know Him…

In the movies and also in real life, there is a phenomenon where you might think a guy is a jerk/mean/etc., but then you learn more about him and see a different side. (A recent example for me was the Woody Harrelson movie “Wilson.”) Although I think the sentiment is often used in an annoying way to cover up for somebody who really is a jerk, you might hear something like, “Oh I understand why people hate him, but once you get to know him like I do, you’d learn he’s really generous and would do anything for his friends…”

It occurred to me that this is the position Christians are in with respect to the God of the Bible. Sure, in the beginning of the story, He’s doing “crazy” things like flooding the whole world out of anger. But then later you see that He’s willing to send His only Son to be tortured to death, in order to save the people He loves.

And in their own lives, Christians would attest that God has done incredible acts of love and mercy and faithfulness. In my own life, things that originally seemed to be gross injustices were actually–I now realize–necessary for my development. The only things in my past I’d want to change were my own failings, not the bad things that “God allowed to happen to me.”

I realize this will likely not count for much for readers who think we’re talking about a fictitious being, but I’ll say it for the record: You would love and trust the God of the Bible if you knew Him like I do.

Potpourri

==> Even though the Fed has merely been rolling over its balance sheet since the fall of 2014, the ECB continues to buy bonds, recently announcing only that it is cutting the size of its monthly purchases (from the current 60 billion down to 30 billion euros) as of this coming January.

==> The provocative but well-documented speech that Joe Salerno gave at the 35th anniversary of the Mises Institute (recently celebrated in NYC), where he pushes back against the claim that Rothbard dropped out of serious economics by the 1970s and just focused on politics/ideology.

==> A very frank essay by Richard Ebeling (my teacher when I was a student at Hillsdale College), in which he acknowledges the willingness of classical liberal heroes (such as Nock and Mencken) to speak out against the institutionalized racism of their day, and yet (Ebeling argues) they didn’t burn with the same moral fervor as the abolitionists had done. Ebeling concludes:

As a consequence, the debates and discussions concerning race, tolerance and the proper institutional order of a free society in an America whose history has been inseparable from the divide between blacks and whites was left almost by default to opponents of racism on the political “left.”

Arguments concerning freedom of association in markets and personal relationships surrounding race problems in America were all predominantly analyzed through the ideological prism of those who considered political paternalism and coercive reform as the only or best avenues leading to racial justice, peace and harmony.

This has now been mutating into the race-based “identity politics” of contemporary America that really threatens a return to a biologically determined classification of individuals, and the “rewards” or “punishments” to be bestowed on all based on the collectivist group category to which the powerless individual has been assigned by ideologically driven “progressive” social engineers.

Friends of freedom, therefore, in my view, must develop ways of breathing life into the philosophy and politics of individual liberty that takes back the moral passion and principled defense of freedom of association on racial issues with the same sense of right and justice with which the classical liberal enemies of slavery brought down that earlier institutionalized system of human bondage. Otherwise, we shall continue our journey on the ideological train of race-based collectivist government planning.

LIVE FROM THE CONTRA CRUISE: Contra Krugman Episode 109

This was a good one. Tom and I really get into the nuts and bolts of different approaches to economics. We springboard from Krugman’s discussion of “rationality” in economics, spurred by the Nobel going to Richard Thaler.

Recent Comments