Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem: The Statement versus Its Proof

Ah! I love this stuff. In a bout of magnanimity I went back and re-read the comments in this Potpourri post, where Keshav and I couldn’t understand why Tel kept asking certain questions about Arrow’s Theorem. (Here’s my follow up which you should also read for more context.) And now I think I get what the problem is. Tel was looking at various proofs of the theorem (such as the one on Wikipedia) and then misunderstanding the definition of a dictator and also the applicability of the theorem.

Let me first make a contrived analogy, which is based on a true story. When I was a little kid, my dad did this trick: “Bob, think of a number. Now double it. Now add 8. Now cut the whole thing in half. Finally, subtract the original number you thought of. You’re thinking of 4.”

That absolutely blew my mind. After he did it a few times, I went and got paper and a calculator, and started picking enormous numbers and then trying negative decimals etc. I couldn’t understand what was going on. [EDITed to add: My dad would change the number that I added each time; I didn’t always end up thinking of 4. So it fueled the illusion that he was literally reading my mind.]

Of course, from my current vantage point, I could easily explain Pat’s Trick using algebraic notation. But suppose the following conversation occurred.

BOB: Ah, I can explain why Pat’s Trick works. Start with some number X. Then double it to get 2X. Now add 8, so you have 2X+8. Cut the whole thing in half–you’ve got X+4. Subtract the original number, you’ve got 4. And yep that’s the number Pat tells you you’re thinking of.

TEL: Sure maybe this works for Ivory Tower PhDs, but when Mark Dice approaches drunk college kids at the beach and says, “Think of a number,” they don’t think of X. They think of a number. Somebody tell me how X is a number? What is it? 1, 2, 3, 4, X? I don’t think so. We don’t count like that in Australia, that’s for sure.

KESHAV: No Tel you’re totally misunderstanding…

CRAW: Actually Tel has a point. According to Pat’s Theorem, it’s possible the person doesn’t know the actual number until the last step. But in the real world, when people think of a number and start manipulating it, at each stage they have a specific number in their minds. So I can see why Tel thinks Pat’s model doesn’t really apply to the world if you tried to have actual people do this trick.

Now to be sure, the above is a bit contrived, and obviously I don’t mean to suggest that Tel/Craw in the real world are being as obtuse as their hypothetical counterparts in the dialog. But I hope the analogy helps.

Specifically, when Landsburg in his proof of Arrow’s Theorem says something like, “But if Mushrooms had come out on top, I could have proved that Bob is an absolute dictator, and if Pepperoni had come out on top, I could have proved that Charlie is an absolute dictator. Regardless of what happened Tuesday, someone must be an absolute dictator,” he didn’t mean that people in society wouldn’t know if they had a dictator on their hands, or would need to see whose preferences get obeyed to figure it out ex post.

Rather, this phrasing is because Landsburg is proving the characteristics of an arbitrary social ranking. He’s assuming we have some rule that generates Social Rankings, and that the rule satisfies the other criteria of Arrow’s Theorem. Then Landsburg uses various considerations to paint it into a corner, and conclude that whatever the rule is, it must be anointing somebody as a dictator. We can’t say in general who the dictator is, because that choice would depend on the specific rule. (E.g. one rule could say, “Social Rankings always match Alice’s rankings,” and another rule could say “Social Rankings always match Charlie’s rankings.”) Landsburg is showing that for ANY rule (that obeys the other conditions), there must exist a dictator. Yes he has to be vague, because we haven’t spelled out the specific rule. Any specific rule would anoint one specific person as the dictator. All Landsburg is showing is that for any rule, there must be such a person.

What Does the Dictator Condition Mean in Arrow’s Theorem?

In the most recent Potpourri post a raging controversy began, which has the ability to rival the Great Debt Debate. The specific motivation was my recent appearance on the Tom Woods Show when I was promoting my Liberty Classroom course on the History of Economic Thought II, and I made a quick mention of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. In the comments of my Potpourri, Tel and Craw said that they thought something was fishy in the way Arrow defined “dictator.” (For what it’s worth, Arnold Kling thinks the same thing–calling it a “swindle.”)

In the interest of education, I am moving the discussion here. I think Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem is one of the most surprising and fun results in formal choice theory, because you don’t need any prior math training to understand the proof. (See Sen’s discussion.) Let me also say that when I first read Steve Landsburg talking about it in The Armchair Economist, I scoffed. “Give me a break,” I thought. “How could a formal proof actually discuss something real-world like elections?” I also spent about 24 hours in grad school thinking I had come up with a counterexample to Arrow’s Theorem. But, I realized my mistake.

So in light of that background, that’s why I am now such an ardent defender of it, because I have been through the crucible.

In one of his comments, Craw wrote:

There is an easy counterexample to your claim. Let there be a unique voter for each ranking and the rule is

Clinton Trump Nader Craw.

Tel had that list so Tel was dictator. If Tel and Kirk swap lists then Kirk is dictator and Tel is not.

It is Kirk’s list which matches the social choice.

No. This is misunderstanding how Arrow’s framework works.

What Arrow is looking for are social choice rules that map from the vector of individual’s subjective ordinal preference rankings (over the elements of some choice set–we can neutrally call it “possible states of the world”) into a ranking of what “society’s” ordinal preferences are. One of Arrow’s conditions (which sounds quite reasonable in some settings but maybe not in others) is that the way Society ranks outcome x versus outcome y should only be a function of how each individual subjectively ranks x versus y.

So for example, a majority-rule social choice function would say, “Society ranks x higher than y if the number of people who subjectively rank x higher than y exceeds the number of people who rank y higher than x.” (Let’s say there is no indifference–where someone thinks x is as good as y–just for simplicity. But Arrow’s framework can handle that.)

Now there’s a problem with using majority-rule as the social choice function. Specifically, if you have at least three citizens and three possible outcomes in the choice set, then you can easily construct a possible list of subjective rankings that lead “Society” to have intransitive preferences. Namely, suppose Person #1 thinks x}y}z (where } means “is preferred to”), while Person #2 thinks y}z}x, and Person #3 thinks z}x}y. There’s nothing weird at the individual level with those preference rankings.

However, if we use a majority-rule social choice function, then we would say Society thinks x}y (because Persons #1 and #3 outweigh Person #2), and we would say Society thinks y}z (because Persons #1 and 2 outweigh Person #3). But oops, our rule also would say Society thinks z}x, because of Persons #2 and #3. So majority-rule social choice functions are in principle vulnerable to constructing intransitive Social preference rankings, and hence Arrow’s framework rules them out.

Another possible social choice rule would simply say, “If Person #2 thinks a}b, for any a,b in our social choice set, then Society thinks a}b also.” This rule would satisfy all of the requirements for a “reasonable” social ranking in Arrow’s framework, *except* it would make Person #2 a dictator. Arrow’s condition of non-dictatorship says that for each person in society, it should at least be possible for there to be a vector of individual preference rankings such that the social preference ranking of some a,b differs from that individual’s ranking. If this is NOT true–in other words, if there exists an individual such that his or her ranking of a,b matches what the Society ranking of a,b is, for all possible a,b in the social choice set and for all possible vectors of individual rankings–then that person is a “dictator” in Arrow’s framework.

So looking again at Craw’s statement above, we see the misunderstanding. Just because in some *particular* listing of ordinal preferences by individuals, the social choice ordering happens to exactly match one individual’s ranking, that alone does not establish that that individual is a dictator.

Let me illustrate by going back to majority rule. Suppose once again the Person #1 has ranking x}y}z. But now suppose Person #2 has ranking x}z}y, and Person #3 has ranking y}x}z. Taking the possible outcomes two at a time, and doing a majority-rule criterion, we determine that Society thinks x}y (Persons #1 and #2), Society thinks y}z (Persons #1 and #3), and finally that Society thinks x}z (Persons #1 and #3). Holy smokes! That means Society thinks x}y}z which is identical to Person #1’s ranking! Does that mean he’s a dictator?

No, it doesn’t. This (I believe) is what Tel and Craw *think* Arrow’s framework implies, and I agree that if it *did*, that would be a pretty screwy definition. (For one thing, if everyone happened to have the same ranking, then every single person would simultaneously be a dictator.) But nope, that’s not what it means to be a “dictator” in Arrow’s framework. With the majority-rule function, we could tweak the individual rankings, and then find that Society ranks some a,b differently from how Person #1 ranks them, and so Person #1 is not a dictator.

Here is Steve Landsburg’s attempt to explain Arrow’s Theorem in simple terms, but again, I point you to Sen’s actual proof that doesn’t require any prior mathematical training. And of course, if you subscribe to Liberty Classroom you can see me explain it–one in plain English, and then again walking through a formal proof using symbolic notation.

Jonah Goldberg on EconTalk on God

Jonah Goldberg is featured in the latest EconTalk, discussing his new book Suicide of the West. It was a very pleasant interview (as these episodes usually are), but there was one thing I found very odd.

Jonah and Russ made several references to God throughout the discussion. (Russ is an observant Jew; I guess I don’t know exactly what Jonah’s beliefs are.) Yet Jonah said he literally opens the book by saying words to the effect that, “God does not appear in this book.” And then near the end of the interview, when the two are discussing whether to be optimistic or pessimistic, Jonah says something like, “Suicide is a choice. There is nothing foreordained about the decline of the West…There is no such thing as a lost cause if people continue to fight.” Jonah also explicitly says more than once during the interview (and in his book) that the birth of liberty in the West was accidental.

I realize this is my Protestant-borderline-Calvinist perspective now shining through, but it seems weird to me that neither of them said, “Of course, since I believe in a loving God, maybe ‘accident’ isn’t the right word, and I’m filled with joy to be alive to see the fruition of God’s plan for humanity.”

Potpourri

Some of these may be duplicates; I have had a hard time keeping up with stuff lately…

==> My latest IER post tackles Krugman’s misleadings claims on renewables. Some pretty graphs!

==> A funny comic on Rothbard, Rand, and Marx.

==> I don’t know how long these have been available, but check out audio clips from Mises!!

==> The only kind of government intervention I support.

==> Contra Krugman 132 goes after the Phillips Curve. Ep 133 is on protectionism (a fun audio clip). Ep 134 has lots of good banter, with some occasional discussion of Krugman to boot. Ep 135 is about renewable energy.

==> My EconLib article on the “power” of statistical tests.

==> David Gordon remembers the recently deceased Leland Yeager, and what Yeager learned from Mises.

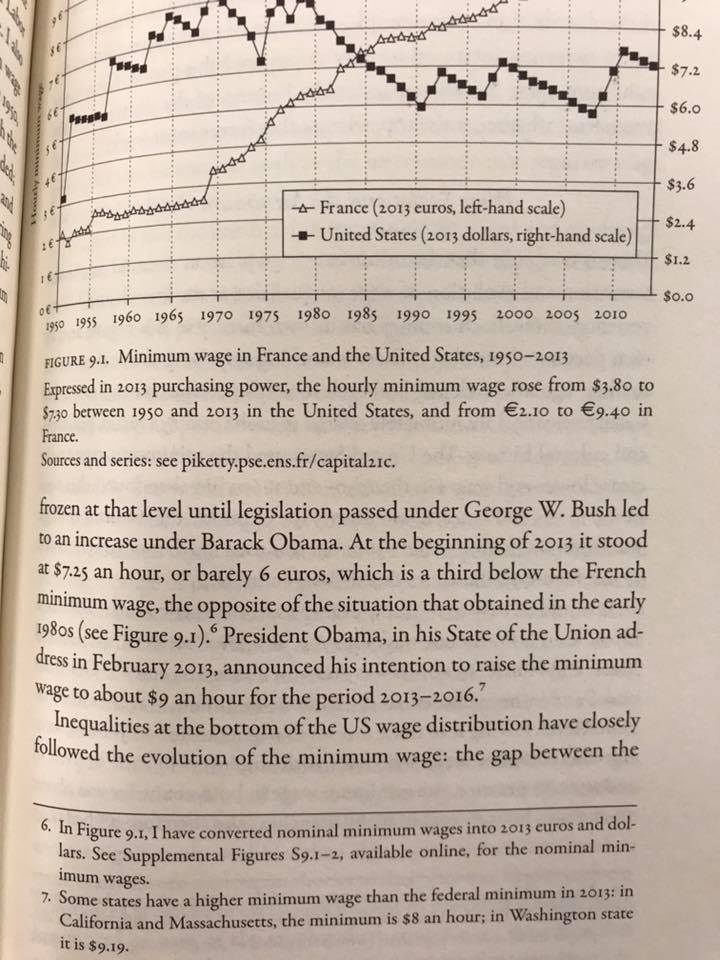

Maybe Piketty Will Fix His Basic Facts in the Third Edition

For the context here, Piketty’s bestseller totally botched the history of the US minimum wage in the post-1980 era, in a way that conveniently praised Democrats and excoriated Republicans. (Phil Magness and I documented it in our paper, but Veronique de Rugy–I think?–was the first person who flagged this one.)

Anyway, someone sent me screenshots of the new edition, and…he fixed some of the mistakes but not all, just in this one section.

My Debate With George Selgin on Fractional Reserve Banking

A good time had by all. Note that comedian Dave Smith warmed the crowd up before we began, and he had a joke in there about a short Mexican guy staring him down. (I allude to the joke twice during the debate; I’m just explaining where that is coming from.)

Christianity and Hell

I have written several posts here on the concept of hell (although the only one I can find right now is this one). I was thinking about it again after watching this trailer of the movie “Come Sunday”:

I think the only way to really make sense of hell is that the sinner in a sense chooses it. Here is CS Lewis: ““In creating beings with free will, omnipotence from the outset submits to the possibility of … defeat. … I willingly believe that the damned are, in one sense, successful, rebels to the end; that the doors of hell are locked on the inside””.

Note that this isn’t merely us being squeamish about the implications of sin. Look at what Jesus Himself said (Mt 23:37, NIV): “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, and you were not willing.”

Reactions to Jordan Peterson’s “12 Rules”

Scott Alexander had a mixed reaction to Jordan Peterson’s book. It starts out very complimentary, but then Alexander ends up wondering whether CS Lewis would view Peterson as an ally or a mortal enemy.

But that’s not really the thing I want to focus on. My own reaction to Alexander’s review was lament. Alexander actually writes this at one point: “But I actually acted as a slightly better person during the week or so I read Jordan Peterson’s book….I tried a little harder at work. I was a little bit nicer to people I interacted with at home.” (Note that the italics is in the original.)

That’s amazing, isn’t it? The book actually made Alexander a slightly better person while he was reading it. So you’d think Alexander would be saluting–

No, that’s not what happened. Here’s the stuff I took out:

Maybe if anyone else was any good at this, it would be easy to recognize Jordan Peterson as what he is – a mildly competent purveyor of pseudo-religious platitudes. But I actually acted as a slightly better person during the week or so I read Jordan Peterson’s book. I feel properly ashamed about this. If you ask me whether I was using dragon-related metaphors, I will vociferously deny it. But I tried a little harder at work. I was a little bit nicer to people I interacted with at home. It was very subtle. It certainly wasn’t because of anything new or non-cliched in his writing. But God help me, for some reason the cliches worked.

And then, here’s the opening of Alexander’s essay:

I got Jordan Peterson’s Twelve Rules For Life for the same reason as the other 210,000 people: to make fun of the lobster thing. Or if not the lobster thing, then the neo-Marxism thing, or the transgender thing, or the thing where the neo-Marxist transgender lobsters want to steal your precious bodily fluids.

But, uh…I’m really embarrassed to say this. And I totally understand if you want to stop reading me after this, or revoke my book-reviewing license, or whatever. But guys, Jordan Peterson is actually good.

Again, the italics is in the original.

And here’s how Alexander ends the essay:

And it makes me even more convinced that he’s [Jordan Peterson–RPM] good. Not just a good psychotherapist, but a good person. To be able to create narratives like Peterson does – but also to lay that talent aside because someone else needs to create their own without your interference – is a heck of a sacrifice.

I am not sure if Jordan Peterson is trying to found a religion. If he is, I’m not interested. I think if he had gotten to me at age 15, when I was young and miserable and confused about everything, I would be cleaning my room and calling people “bucko” and worshiping giant gold lobster idols just like all the other teens. But now I’m older, I’ve got my identity a little more screwed down, and I’ve long-since departed the burned-over district of the soul for the Utah of respectability-within-a-mature-cult.

But if Peterson forms a religion, I think it will be a force for good. Or if not, it will be one of those religions that at least started off with a good message before later generations perverted the original teachings and ruined everything. I see the r/jordanpeterson subreddit is already two-thirds culture wars, so they’re off to a good start. Why can’t we stick to the purity of the original teachings, with their giant gold lobster idols?

So to sum up: Scott Alexander starts off by mocking him, then admits he became a better person while reading the book and that Jordan Peterson himself is a good person who is trying to make the world better and wrote a “really good” book to do so, and still wraps up the essay by mocking him. What the hell? It’s like a high school bully telling the other bullies, “Yeah, I was in the midst of giving Eugene a swirly, and he actually made a decent point, that maybe I should reconcile with my father. I actually called up my dad and said we needed to talk. Then I gave Eugene a wedgie and stuffed him in the locker, that dork.”

For Russ Roberts’ reaction, see here.

Recent Comments