The Fairest Keynesian in the Land

When I look upon my mirror and ask it to name me the fairest Keynesian in the land, he says Mecha Lekka Hi Mecha Hiney Ho. But when prompted again, he says it’s Karl Smith. For example, in a recent post Karl put a picture of Ron Paul’s End the Fed and then said this:

I have been a staunch supporter of an independent central bank technocratically solving the problem of macroeconomic management

Yet, now I must watch as one of the most powerful Central Bank in the world, the Federal Reserve, can’t come to consensus on what it wants to do and has decided that perhaps Rome should burn just a little bit more while it has additional meetings on the relative merits of bucket brigades versus opening the aqueducts.

Its counterpart the European Central Bank, has apparently decided that what the fire really needs is a bit more oil, lest the people think the bank is more committed to putting out fires than lecturing people on fire prevention.

Let us not even speak of the Bank of Japan which perhaps should be disbanded out of mercy for the central bankers if nothing else.

I have not lost all faith –Sweden and Switzerland still stand – but it is hard to watch this carnival of human suffering and believe that we supporters of central banking are not part of the problem.

And that’s the whole post. There’s not a “P.S. John Taylor drowns kittens for sport” at the tail end. Nope, Karl isn’t throwing in the towel, but he’s at least acknowledging that there might be something wrong with his position.

In contrast, our more famous Keynesians bloggers are so out of touch with their opponents that–get this–Matt Yglesias tries to prove that Paul Krugman doesn’t always support big government, by linking to an article from 2000 (Yglesias has a typo and says 2008) in which Krugman opposed tax cuts. Yes you read that right: Yglesias was trying to show that Krugman sometimes is a fan of smaller government, by linking to an article where Krugman deployed economic analysis to oppose tax cuts.

(In case you are too busy to click the links, I’ll give you the trick: Yglesias subconsciously took “supporter of bigger deficit” ==> “supporter of bigger government” and thus concluded that “opponent of tax cuts that would give a big deficit” ==> “an opponent of bigger government.”)

So in conclusion, I can recognize fair Keynesians when I see them. I don’t pounce on Krugman because he presses for big government–I pounce on him because he is the epitome of a partisan hack (on his blog), and has the audacity to lecture others on their ideological biases. (I also obsess with Krugman because he’s such a good exponent of the Keynesian view. Like Russ Roberts, I claim that Krugman picks his conclusions based on his ideology, but I love Krugman because he tries to demonstrate his conclusions using economic models.)

Karl Smith is a Keynesian, and some of his positions shock me, but I think he is a fair guy and is just honestly mistaken. Maybe give the guy a spell checker, and the truth will eventually out.

The Most Klassic Krugman Kontradiction of All Time

This actually made me get up and pace around the office for a minute. I had to let it sink in, it was so delicious.

First, the context: People have the long knives out for Russ Roberts, who had disputed the evidence that Krugman had given for a Keynesian worldview, and then Russ Roberts concluded:

Krugman is a Keynesian because he wants bigger government. I’m an anti-Keynesian because I want smaller government. Both of us can find evidence for our worldviews.

Now that was a surprising thing for Roberts of all people to say (as even Daniel Kuehn agreed). For example, if you listen to this EconTalk podcast where Roberts interviews a card-carrying Keynesian, Roberts is the model of courtesy. There are lots of people in the liberty movement for whom the above statement might be accurate, but Roberts would not have been near the top of my list.

So perhaps he mistyped, and meant to say something more like, “There aren’t controlled experiments in economics, and to be honest I think we all bring our biases to the table. I can look out and see all sorts of ‘objective’ evidence that Keynesian policies fail, but I have to be fair and admit Krugman can see just the opposite. In the grand scheme, I can’t honestly say my evidence is more objective than his. Of course I truly believe I’m right, but let’s be frank, maybe I can’t help but feel that way.”

Anyway, back to Krugman today and his predictable reaction to Roberts’ candid admission:

What is true is that some conservatives in America have always opposed Keynesian thought because they believe it legitimizes an active role for government — but that’s not what Keynesianism is about, and not the reason I or others support it.

…Russ Roberts may choose his economic views because they support his political prejudices. I try not to. Maybe I sometimes fall short — but I try to analyze the economy as best I can, never mind what’s politically convenient, and indeed to bend over backward to avoid believing things that make me comfortable, to avoid turning everything into a morality play that confirms my political values.

OK here my BS meter was off the charts. Since I have been reading Krugman, I can’t think of a single episode where there has been economic or political controversy, and Krugman used his economic analysis to weigh in on the side of the group wanting smaller government on that particular issue. I’m not saying Krugman is a full-blown socialist, I’m saying that when he jumps into a fight, I can’t ever remember him delivering uppercuts to the people whose position happens to imply a smaller bigger role for government.

(In case you think I’m being a hypocrite, I have–on very rare occasions, to be sure–grudgingly conceded that Krugman/DeLong had a point on something, and that my free-market brethren were being inconsistent in their arguments. It’s true, I have never come out and called for more government powers, but I do try to be mindful of the distinction between economic analysis and moral considerations. I can’t find the best examples of this, but after looking for a few minutes I came up with this post, where I defended Krugman from Scott Sumner and Pete Boettke. Of course, you could claim that my anti-Sumner anti-GMU bias just outweighed my anti-Krugman bias there; perhaps so.)

Anyway, as if sensing that people would be skeptical, Krugman then offers up an example of how he doesn’t make economics a morality play:

Here’s an example: is economic inequality the source of our macroeconomic malaise? Many people think so — and I’ve written a lot about the evils of soaring inequality. But I have not gone that route. I’m not ruling out a connection between inequality and the mess we’re in, but for now I don’t see a clear mechanism, and I often annoy liberal audiences by saying that it’s probably possible to have a full-employment economy largely producing luxury goods for the richest 1 percent. More equality would be good, but not, as far as I can tell, because it would restore full employment.

So I’m trying to figure this thing out, as best I can. If you’re not, we’re not in the same business.

OK, I put the “often annoy liberal audiences” in bold. I want someone to show me one time in his blog where Krugman ever made that point. I’m not betting my life that he didn’t, just saying I can’t ever remember him saying it.

And now, what you’ve all been waiting for. The Most Klassic Krugman Kontradiction of All Time. After the above post, where Krugman pats himself on the back–in contrast to that ideologue Russ Roberts–for his willingness to not mix up issues of inequality with the causes of our downturn, IN THE VERY NEXT #)$(#$* POST, Krugman writes:

A wonderful juxtaposition:

Max Abelson reports on the sorrows of the financial elite:

An era of decline and disappointment for bankers may not end for years, according to interviews with more than two dozen executives and investors. Blaming government interference and persecution, they say there isn’t enough global stability, leverage or risk appetite to triumph in the current slump.

…

Options Group’s Karp said he met last month over tea at the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York with a trader who made $500,000 last year at one of the six largest U.S. banks.

The trader, a 27-year-old Ivy League graduate, complained that he has worked harder this year and will be paid less. The headhunter told him to stay put and collect his bonus.

“This is very demoralizing to people,” Karp said. “Especially young guys who have gone to college and wanted to come onto the Street, having dreams of becoming millionaires.”

Meanwhile, Catherine Rampell reports on Bankers’ Salaries vs. Everyone Else’s, telling us that

the average salary in the industry in 2010 was $361,330 — five and a half times the average salary in the rest of the private sector in the city ($66,120). By contrast, 30 years ago such salaries were only twice as high as in the rest of the private sector.

It would all be hilariously funny if these people weren’t destroying the world.

An interesting juxtaposition indeed. Not an actual contradiction, of course. A Krugman Kontradiction. He can’t be convicted in any court, but boy oh boy 99% of his readers will get the message.

Who Wants to Be My Synthetic Friend?

OK I broke down and joined Twitter. (It has to do with the Washington Times gig; they are really pushing us to be social or something.) So, if you are so inclined, follow me @BobMurphyEcon.

Sumner Plugs the Last Chink In His Inflationist Armor

I know many of you are probably getting sick of my obsession with econo-blogger Scott Sumner, but he is really something else. In previous posts I have shown that Sumner has explicitly declared that even if his policies lead to nothing but rising price inflation, he will have no regrets. Yesterday he made his views even more explicit by declaring:

I often argue that if we do eventually get high inflation, the cause will most likely be tight money over the past few years.

If you’re a “fair” person who likes to read people in context, by all means click on the link; Scott is talking about Sargent and Sims winning the Nobel (Memorial) Prize, and how their work on expectations leads to the line quoted above.

I am bringing this up just to bolster the Austrian faithful. Perhaps you’ve been huddled in your treehouse, double- and triple-checking that you have a can opener to go with your three years’ supply of tuna fish and spam. You’ve been checking the monthly BLS releases, saying, “It’s taken longer than I would have guessed, but eventually even the government won’t be able to hide the skyrocketing prices I see at the grocery store. Then Sumner will admit he’s been wrong all along!”

No he won’t. It will be further proof that Bernanke had a “contractionary” monetary policy from 2008-2011.

On a more serious note, just a comment on the Sumner/DeLong exchange: Scott comes back and defends his approach in this post. If I may paraphrase, Scott is saying that we should define terms like “easy money,” “tight money,” “contractionary monetary policy,” etc. with reference to the goals of the policymakers. In this approach, since Scott thinks the Fed should be aiming to make nominal GDP grow at a steady 5% rate, then Bernanke’s Fed has clearly been too “tight” the last three years.

I understand where Scott is coming from, but I reject his arguments. The primary reason is that what if Sumner’s worldview is totally wrong? By interpreting the policies of the central bank through the prism of Sumner’s preferred goals, we begin to lose touch with reality. It makes it harder for economists to decide whether the goals are the right ones to adopt.

For example, since 2009 Paul Krugman has famously said that the Obama Administration’s fiscal expansion wasn’t expansionary enough. Yes, they ran a big deficit, but not big enough.

OK fair enough. We can debate that (and we have, ad nauseum).

But in Sumner’s approach, we would no longer say that. Instead, we’d say that Treasury Secretary Geither by definition implemented a contractionary fiscal policy since assuming power, because unemployment is below the policy goal. The only way we could classify a deficit plan as “expansionary” is if we got back to full employment.

Does anybody think that would make sense? I hope not. It would be way too confusing, especially since a bunch of economists disagree with the Keynesian approach of using big fiscal deficits to reduce unemployment.

So by the same token, since many Austrians (among others) TOTALLY DISAGREE that expansionary monetary policy is needed for economic recovery, it would be crazy to classify Bernanke’s policies as “tight money.” As DeLong has said, we have plunging nominal and real interest rates, and a tripling of the monetary base. What else would qualify as easy money?

A Tale of Two Krugmans

On Sunday Paul Krugman wanted to nip in the bud the small-government fantasy that the way to deal with reckless bankers is to stop bailing them out:

One line I’ve been seeing in various places, including comments here, is the claim that the real way to deal with Wall Street is laissez-faire economics: no more bailouts! On this view, policy makers should raise their right hand in the air, place their left hand on a copy of Atlas Shrugged, and swear in the name of A is A that they will never again step in to rescue failing banks. And all will be well with the world.

Sorry, but that’s a fantasy.

…[E]ven if you persuade yourself that the moral hazard created by financial firefighting outweighs the benefits of avoiding a 1931-style cascading crisis, the fact is that policy makers will intervene. Hank Paulson set out to make Lehman an example; two days later he was staring into the abyss.

So the only feasible strategy is guarantees and a financial safety net plus regulation to limit the abuse of those guarantees.

So since Krugman gets to just declare that his view is the only politically feasible one, he wins. It’s not like there’s a role for heterodox economists to recommend crazy stuff like letting insolvent banks fail. That could never happen in our modern world, even if you thought it was a good idea.

Then again, Krugman wrote this in November 2010, contrasting the fates of Ireland and Iceland:

What’s going on here? In a nutshell, Ireland has been orthodox and responsible — guaranteeing all debts, engaging in savage austerity to try to pay for the cost of those guarantees, and, of course, staying on the euro. Iceland has been heterodox: capital controls, large devaluation, and a lot of debt restructuring — notice that wonderful line from the IMF, above, about how “private sector bankruptcies have led to a marked decline in external debt”. Bankrupting yourself to recovery! Seriously.

And guess what: heterodoxy is working a whole lot better than orthodoxy.

Now it’s true, Krugman wasn’t recommending a Ron Paul Option for Iceland. But my point is, he was recommending something that would prima facie seem to be politically impossible, according to his post from two days ago.

So, when Krugman doesn’t like a particular measure, he declares it politically impossible. When Krugman advocates something that doesn’t end up getting done (like a bigger stimulus), he doesn’t conclude that the fault is his own (for recommending the impossible), but whines for two years that everybody else is an idiot for not heeding his warnings.

Boehner Boom Baby?

When he’s not trying to be the Moment of Zen clip on the next episode of the Daily Show, University of Rochester economist Steve Landsburg showers some love on Paul Krugman. After quoting Krugman saying:

Here’s a question I haven’t seen asked: If fear of future regulations and taxes is holding business back, as everyone on the right asserts, why didn’t the Republican victory in the midterms set off a surge in employment?

After all, if you really believed that fears of Obamanite socialism were the key factor depressing employment, the GOP victory — with the clear possibility that the party will take the Senate and maybe the White House next year — should greatly reduce those fears. So, where’s the hiring surge?

…Landsburg says to his readers:

…I can come back to the bit about the missing Boehner Boom. It’s a more-than-fair question. How would you respond to it?

Well Steve, the first thing to do is check to make sure the data aren’t the exact opposite of the story Krugman is pushing. “What the heck are you talking about, Bob?” you ask. Well, you tell me. Suppose that there were in fact a “Boehner boom.” What would the data look like?

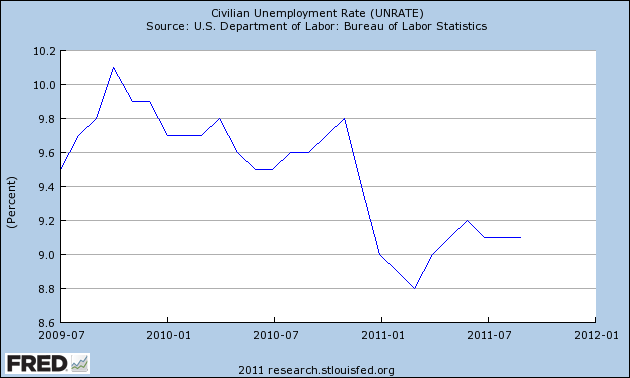

I suppose–hypothetically speaking here–that if, say, unemployment had been steadily rising, then stopped on a dime in the month when the Republicans won big in the 2010 elections, and then had the largest sustained drop of any period since the recession began, in fact far larger than any drop or surge that Krugman has used to vindicate his predictions regarding the stimulus coming and going…then that might be prima facie evidence for a “Boehner boom.” Of course it wouldn’t prove anything definitively, since there was QE2, people started anticipating a Republican rout as the elections got closer, everything in economics is ceteris paribus, etc.

Still, if unemployment had been steadily rising, then peaked in November 2010 and fell like a stone thereafter, dwarfing any other swings in unemployment since the recovery officially began, then surely that would put the Keynesians on the defensive, and it would bolster the people blaming the interventions of the Obama Administration for the sluggish economy, right?

Anyway, here’s the chart:

I actually have a surge in “real work” so I won’t be able to blog much for a while. I will let the professional pundits do what they will with the above, but I thought it was worth bringing up.

Tom Woods and Stefan Molyneux

I had this going while I balanced my checkbook yesterday. Good stuff. Tom makes some eloquent points, and Stefan has a few hilarious one-liners. The only strange thing is that Stefan seems to be constipated throughout the interview; watch his face as Tom speaks.

Fiat Money and the Euro Crisis

My article today at Mises:

Lost in all the analysis of the theory of “optimal currency area,” the possibilities for a structured default, the consequences of a collapse of the euro, etc., are two simple questions: Why does the behavior of the Greek government have anything to do with taxpayers in Germany? Why did the original Maastricht Treaty have rules about fiscal policy as part of the criteria for monetary union?

The answer is that the euro is a fiat currency, and as such it will always provide rulers with the temptation to monetize fiscal deficits.

and

I tried to illustrate the point to my Slovakian audiences with a thought experiment: Suppose that instead of the fiat approach, the euro from day one had been backed 100 percent by gold reserves. In this arrangement, an organization in Brussels would have a printing press and a giant vault. Anybody around the world — whether private citizens or foreign central banks — could order up euros, so long as they deposited the fixed weight of gold in the vault. Thus, at any given time, every single euro in circulation would be backed up by the corresponding gold in the vault in Brussels.

In this scenario, the people issuing the euros wouldn’t have to run a background credit check on the people applying for new notes. So long as the requests were made with genuine gold, the people printing euros wouldn’t care if the applicant were the German government or Bernie Madoff. Even if some other country had adopted the (gold-backed) euro as its own currency, and then that government defaulted on its bonds, there would be no repercussions for the other regions using the euro as money. People would know that their own euros were backed 100 percent by gold in the vault in Brussels, just as always.

Recent Comments