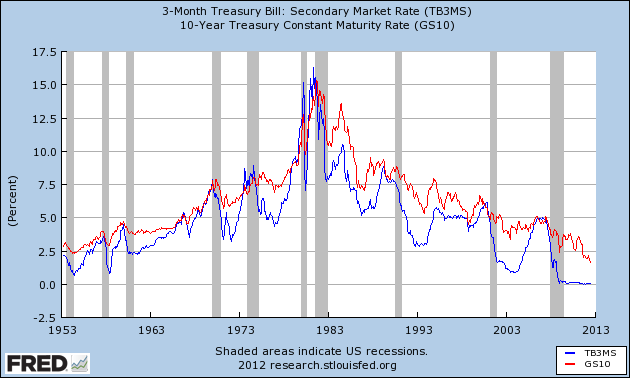

Updated Yield Curve Chart

For my Anatomy of the Fed class, I showed how the Austrian theory of the business cycle actually has a very natural explanation of the yield curve’s ability to “predict” recessions. (Details in my paper here.) Some people asked me to update the charts. Here ya go:

Revisiting the Economics of Climate Change: Nordhaus, Tol, and Surprising Findings

I have a long post up at MasterResource, revisiting the issues that came up in my earlier response to Nordhaus. If you are interested in climate science, particularly the economics of climate change, I would immodestly recommend that you wait till you have a good 15 minutes and read this thing through. It’s by no means a “light” piece but I think there are some important issues that I cover.

For the economists reading, let me reproduce a large portion of one of my arguments:

In a standard economic regression analysis, we typically approach things the way one is taught in high school when learning basic statistics. Namely, you set up a null hypothesis that is the opposite of the causal relationship you (the researcher) actually think exists. Then, if there is an apparent relationship in the data (such that you get a positive value on the coefficient for a certain term in a least-squares regression, say) you can see if the result holds up at a 90 percent, 95 percent, or 99 percent confidence interval.In this normal context, the higher the confidence interval, it means the more confident you are that the apparent relationship between two measured variables isn’t spurious….Yet in charts of climate model projections, the “confidence interval” works the other way around. Here, the higher the number, the less confident we can be that an apparent match between the model and nature is due to the underlying accuracy of the model. To put it in other words, here the null hypothesis is that “this suite of climate models is accurately simulating global temperature.” Thus if we make it harder to reject the null (by ramping up the confidence level), then it gives more wiggle room for the models.Specifically, the “95% range” in the second graph above comes from looking at all of the observed “runs” of the suite of climate models, and then plotting the gray boundary that captures the realizations of 95% of the runs centered around the average. Ironically then, the less agreement there is between the individual climate models, then the wider the gray zone would be, and the harder it would be for Nature to “falsify” the suite of climate models.…Suppose for the sake of argument that one particular model accounted for 3% of the total simulated runs, and it predicted global temperature anomalies of 20 degrees Celsius from the year 2010 forward, while another particular model accounted for a different 3% of the total simulated runs, and it predicted global temperatures of minus 20 degrees C from 2010 forward.In this (absurd) situation, the RealClimate post would show a massive gray zone covering the “95% confidence interval,” and (barring an asteroid collision or a massive change in the sun), it would be inconceivable that temperature observations would fall outside of this range. Yet that would hardly shower confidence on the suite of models.

How to Amaze Jesus

I read a familiar gospel passage the other day, but took something away from it that had previously escaped my notice (in bold below):

Mark 6:1-6

New King James Version (NKJV)

Jesus Rejected at Nazareth6 Then He went out from there and came to His own country, and His disciples followed Him. 2 And when the Sabbath had come, He began to teach in the synagogue. And many hearing Him were astonished, saying, “Where did this Man get these things? And what wisdom is this which is given to Him, that such mighty works are performed by His hands! 3 Is this not the carpenter, the Son of Mary, and brother of James, Joses, Judas, and Simon? And are not His sisters here with us?” So they were offended at Him.

4 But Jesus said to them, “A prophet is not without honor except in his own country, among his own relatives, and in his own house.” 5 Now He could do no mighty work there, except that He laid His hands on a few sick people and healed them. 6 And He marveled because of their unbelief. Then He went about the villages in a circuit, teaching.

Normally gospel accounts talk about people marveling at Jesus, not the other way around. And unfortunately, this isn’t a good type of marvel. (You do see the opposite in the famous story of the centurion asking Jesus to heal his servant, where Jesus marvels at his faith.)

Now the reason this resonated so much for me is that when I argue with some of you on these Sunday posts, I marvel at your unwillingness to even consider what it would mean if you were wrong. The problem here is that we are dealing with the most important, foundational issues of someone’s worldview. It’s one thing if, say, you and I are both Austro-libertarians, and you say you think fractional reserve banking doesn’t cause business cycles but I say maybe it does. We agree on 99% of how to approach the problem, and we just diverge right at the moment when we’re putting the punctuation mark at the end of the sentence.

In contrast, if I think a loving God created all of the universe, and every bad thing happens because it fits into God’s beautiful plan of mercy and redemption, and furthermore that we can see God’s fingerprints screaming out from every area of intellectual inquiry…whereas you think that we are statistical quirks in one of an uncountably infinite number of possible universes, that “the real world” consists of atoms in motion and nothing else, that there is no purpose to existence at all, and that things like love, mercy, and the aching for knowledge of the divine are at best useful behaviors that cannot be justified rationally, but at worst vestigial emotional wiring that at one point conferred an evolutionary advantage… Well holy cow, it’s going to be hard for us to have a conversation.

Anyway, back to the passage quoted above: I hope this underscores one of the main points I have made time and again on these Sunday posts. Despite the claims of the “rational, empirical” atheists, when a religious person speaks of “faith,” he does not mean “a willingness to throw one’s reason out the window.”

No, not at all. In the context of the story (which is the only way to judge this, because we’re talking about how religious people use words right now), Jesus had been going around performing all kinds of miracles. So in light of that empirical evidence, it is the height of absurdity for someone to say, “Wait a minute, this guy couldn’t possibly be a big deal. So what if we’ve heard that he healed a bunch of people, or that we’ve seen him give astonishing sermons with our own eyes. I mean, we knew him when he was 5 years old!” What kind of argument is that? It causes one to marvel. Jesus is amazed because He can see that no matter what He does or says, these people absolutely refuse to consider that He might be telling the truth.

Last thing: I know a bunch of you are going to say things like, “This is silly. Jesus never healed anybody. Those are claims in a story. Do you believe in Hercules too Bob?” That’s not the point I’m making here. I’m saying that religious people use “faith” the same way Vader does in that famous scene. The point is, it’s actually quite anti-empirical and “superstitious” for that guy to doubt Vader, in the context of the story that George Lucas is telling. We shouldn’t applaud that “skeptic” for his devotion to the scientific method; instead we should tell him that his pigheadedness and refusal to consider the wealth of evidence staring him in the face, almost got him strangled to death.

Krugman Was Against Peak-to-Trough Calculations Before He Was For Them

Here I am, in beautiful Florida minding my own business, when Krugman comes out with yet another Kontradiction screaming for a reaction. So even though I’m on vacation, and yet spending 6 hours a day on my “real work,” duty compels me to comment. On July 3 Krugman started out a blog post like this:

I’m in Madrid, doing 45 trillion interviews, so not blogging much. But I was alerted to a remarkably stupid attack on me over the subject of Iceland from the Council on Foreign Relations — and I use that term advisedly.

Whoa! I can’t dig it up right now, but I have said in the past that I don’t think Krugman is part of the global Soros conspiracy, simply because he’s too arrogant and a loose cannon; they couldn’t trust him to keep his mouth shut. (It’s possible I am not in the Inner Circle of the Vast Right Wing Conspiracy for similar reasons.) This right here is stellar confirmation of my earlier judgment. Dr. Krugman, it’s one thing to politely disagree with the CFR. But to call one of their pieces “remarkably stupid” and then to go on and actually mock their very name?! Are you mad, bro? Hillary Clinton referred to their HQ in New York as the “mother ship.” Let me put it this way, Dr. Krugman: You know how you think to yourself, “Yeah, I blew up that opponent the other day…” ? Well, the CFR guys think that too–except they’re not being metaphorical. You think this is some academic disagreement over peak vs. trough? Not so, my good doctor. You are challenging the euro project, and the globalist elite isn’t taking kindly to such criticism.

Anyway, back to Krugman’s post:

The CFR people take me to task for measuring economic performance in Iceland and the Baltics relative to the pre-crisis peak, which they suggest is some kind of scam. Why not measure relative to the post-crisis trough, under which the Baltics look better?

Oh, boy. Economists have been studying business cycles for something like 90 years, and done comparisons to previous peaks all that time; apparently these guys don’t know about any of that. So let’s try this slowly.

First of all, we think of a recession as a period in which the economy falls below its potential; the natural way to gauge a recovery is to see how much of the lost ground has been regained.

Better yet, compare two hypothetical countries — call them country I and country L. Both suffer from a severe economic setback, but country I does a better job of responding to the shock, so that output falls only 10 percent in I but 20 percent in L. Then both economies recover. In that recovery, output in L grows more from the trough than output in I — but only because the country did so badly in the first place. Yet the CFR people would have us believe that L, not I, is the success story.

Or do a bit of history. The US economy grew 10.9, yes, 10.9 percent in 1934. The New Deal triumphant! Or maybe not. Real GDP was still about 20 percent below its 1929 level.

So by comparing output to the previous peak I’m doing the obvious, natural thing; the CFR alternative makes no sense.

A few things:

(1) Krugman is, as usual, treating his opponents as 3rd graders. I’m pretty sure the author(s) of the CFR piece understand full well the general framework of how economists might look at the business cycle. Go read the article and see if the author(s) are being as dumb as Krugman implies. In particular, they are talking about his disparaging of the euro project, and that’s why they are including the data from the year 2000 onward. Yes, if Krugman pretends their point is something else, then they look stupid. That’s pretty easy to do, if you distort when somebody else’s point is.

(2) The point about the New Deal is absolutely hilarious. That type of argument is precisely what Keynesians cited when arguing over the Obama stimulus. For example, when warning us not the repeat the “mistakes of 1937,” Christina Romer wrote:

[T]he recovery in the four years after Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933 was incredibly rapid. Annual real GDP growth averaged over 9%. Unemployment fell from 25% to 14%. The second world war aside, the United States has never experienced such sustained, rapid growth.

However, that growth was halted by a second severe downturn in 1937–38, when unemployment surged again to 19% … The fundamental cause of this second recession was an unfortunate, and largely inadvertent, switch to contractionary fiscal and monetary policy. [Spending cuts and tax hikes] reduced the deficit by roughly 2.5% of GDP, exerting significant contractionary pressure.

And yet, right in that same time frame, Krugman was approvingly citing her analysis in his NYT op eds. I guess the Ombudsman took out Krugman’s attacks on Romer for being “remarkably stupid” since it is impolite to say such things about a lady.

(3) Krugman should understand where the CFR people are coming from, when they specifically explain that the previous peak might not be a good measure in this case, since they had argued at the time that it was above “potential GDP.” I say that Krugman should get the general gist of this, since, in an earlier post when he was championing Iceland as the poster child for his policy recommendations, Krugman put up a chart of its GDP path over the years and commented:

GDP is still below previous peak, but I think one could argue, much more so than in say America, that a significant part of that peak involved a Ponzi financial sector that isn’t coming back.

I think I was one of the first outsiders to notice that Iceland’s heterodoxy was yielding a surprisingly not-so-terrible post-crisis outcome.

Scott Sumner busted him at the time, but in the present context we can simply say: Paul Krugman must have been remarkably stupid when he wrote that.

Feynman Bask

OK you scores of atheist readers, now’s your chance to make up for your hurtful Sunday commentary. I am trying to get my hands on Richard Feynman’s discussion (in one of his pop books, I’m almost certain) of when he was in a South American country, and the president (?) asked him what he, Feynman, thought of their educational system. Feynman said he was sorry to report, but the only promising grad student he had encountered while visiting, was someone who came from a European (?) country. Feynman’s basic point was that this South American country’s culture raised students to be very deferential to the textbooks and established authorities in science, and that that was a recipe for stagnation.

So, can people give me the citation and, if possible, a few paragraphs of the exact text? I made need to actually quote it for something for which I have a tight deadline.

Thanks. (And FYI the atheist references are because of lot of you cite Feynman to make me feel bad on Sundays.)

God, the Hidden Tyrant?

Just a quick note: A while ago I linked to a 10-minute Christopher Hitchens video, in which he set out to disprove the existence of God. What he actually did was argue why the God of Western monotheism was a tyrant, and why he (Hitchens) was glad such a God didn’t exist. One of the reasons Hitchens gave, was that if the God of the Bible were true, then He would be a worse tyrant than Kim Jong Il–at least you could die if you were stuck in North Korea.

Yet something wasn’t sitting right with me, and today I put my finger on it. It’s very odd that atheists condemn the God of the Bible for being such a tyrant, and they also ask Christians, “If your God exists, then why is He hiding?” That’s an odd sort of tyranny to be exercising, that a lot of people doubt the tyrant exists. I imagine nobody in North Korea had any doubts that there really was a government that would lock them up if they stepped out of line.

Now look, I understand the atheist position: He is saying (a) the stuff that the God of the Bible does, in that fictitious book, is crazy and tyrannical, and (b) thank goodness there is no scientific evidence that such a being actually exists.

But I can just flip it around and ask the atheist to see things from the Christian perspective. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that we are right. Then your case falls apart. You can’t accuse God of micromanaging our lives, when you also demand that He show Himself.

Let me put it this way to try to make my point clearer: There are atheists who recoil at horror at the idea that there could be some being in ultimate control of the universe. At the same time, there are atheists who recoil at horror at a being that stands idly by with the power to prevent wars and infant mortality, yet chooses not to. It would make sense if these were different groups of atheists. And yet, I think just about every modern atheist falls into both camps simultaneously. Isn’t that a bit weird?

(Note well, I am using the term atheist quite consciously. If there are people who are really just not sure, OK fair enough. In this post, I am talking about the people who are confident that there is no God, for the types of reasons above.)

What’s really ironic is when libertarian, free-market atheists hold the above positions. One way of describing their views is that they (a) think God should be intervening a lot more to punish evildoers on Earth, but (b) can’t believe that He apparently punishes people in the afterlife for not having the right belief system. So it’s not that they are “for” or “against” intervention; they rather think God should be intervening differently.

Again I ask: Suppose for the sake of argument that there really were a God, who literally knew everything. Isn’t it just possible that there are a few pertinent details escaping our notice, when we have observed one droplet of human existence in an ocean of history, and we have almost no idea of what the future holds? For people who recognize the fatal conceit and the problems of central planning in human affairs, it is funny to hear them second-guessing God and say things like, “Well geez, if humans and other organisms were actually intelligently designed, they would look like XYZ. So clearly they weren’t.”

Last point to deal with an obvious retort: The atheist libertarian can’t just flip this around and say, “Right Bob, you of all people should know the dangers of central planning, so why do you revere the ultimate central planner?” And the answer is, because He’s God. That’s a pretty good response. It’s why we have expressions like, “That’s dangerous because we’d be playing God.” If anyone is allowed to play God, it is…God. Maybe He doesn’t exist, but if He does, then, yes, it’s OK to have an omniscient, omnibenevolent being running the show. In fact it gives immense relief and comfort to know that He is.

Potpourri

==> Oh boy, here we go again, flirting with the event horizon in economics known as capital & interest theory. If I were an academic, puffing on my pipe and flaunting a tweed sportcoat, I could really get into this. As it is, you will have to content yourself with my comments in Nick Rowe’s post. Anyway, here is Nick and then David Glasner talking about the Sraffa-Hayek debate. (Others like Daniel Kuehn are involved, but you can follow the links to see all the blogosphere fun.) I am pretty sure I agree with everything those two guys say, except when they conclude (Nick explicitly, David implicitly) that Sraffa’s point wasn’t so hot, in the famous debate. As I point out here in this heretical paper, yes it was a big deal, and in particular, Ludwig Lachmann’s attempt to solve the problem fails completely. I am not throwing out Austrian business cycle theory–that’s what I try to rehabilitate in that very paper–but I don’t think Austrians have done a good job at all in responding to Sraffa’s challenge, which was perfectly fair in the context of that debate. To wit, Hayek had recommended that the monetary authority do something that was impossible. I don’t see why Sraffa is out line for bringing up that awkward fact.

==> This guy at The American Conservative didn’t like my utopian approach to the marriage question.

==> Speaking of TAC, here is a piece from a while back that I forgot to post. I take on the claim by Lawrence Summers, Brad DeLong, and Gene Callahan that governments should borrow more right now, and be acting like smart businesses.

==> This article condemning the Confederacy for going to war is amazing because it never occurred to the author that all of his arguments could be used…to condemn the North for going to war. The Confederate states didn’t invade the North in order to protect slavery, rather they wanted to secede and be left alone. The North said, “Nuts to that,” and sent in generals who burned their cities to the ground. If the author wants to say today’s libertarians shouldn’t be talking about this, because it’s strategically silly for us to waste time “defending” slave owners, OK I’ll listen to that argument, but as it is this piece makes no sense to me. If anything, it proves the opposite of what the author intends.

==> Mario Rizzo reminds us that Bloomberg’s soda ban isn’t the only dumb thing going on in New York.

==> The crafty veteran economist David R. Henderson shows me how to find a Krugman Kontradiction old-school style. The topic is what the “Keynesian” prediction on inflation was in the early Reagan years, and it is simply breathtaking how confidently Krugman yells at his opponents and accuses them of making stuff up, when he himself spouted the views that they are attributing to Keynesians. Wow.

==> Another Henderson post, this time on the oft-heard claim that if we had conscription, the politicians would think twice before plunging us into another war. I give David and his co-author some pushback in the comments, just keeping them honest.

==> Apparently Tom Woods has had people ask him about Webster Tarpley too.

Recent Comments