Federal Government Changes Own Recommended Discount Rate When It Comes to Climate Change

[UPDATE below.]

As I explained when the May update came out, the Obama Administration’s “working group” on the “social cost of carbon” reports figures that vary crucially depending on the discount rate we choose. According to the updated document, the negative externality associated with one ton of carbon dioxide emissions in the year 2010 was:

==> $11/ton at a 5% discount rate,

==> $33/ton at a 3% discount rate,

==> $52/ton at a 2.5% discount rate.

You can see how much the discount rate matters on this issue. (The reason is that the computer-simulated damages don’t really start accruing until several decades in the future.)

Now this raises the interesting question of, “Which discount rate should the government use?” Oh if only there were some guidance!

Fortunately, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) provided the following guidance in its 2003 update to Circular A-94:

2. Real Discount Rates of 3 Percent and 7 Percent

…

As a default position, OMB Circular A-94 states that a real discount rate of 7 percent

should be used as a base-case for regulatory analysis. The 7 percent rate is an estimate of the

average before-tax rate of return to private capital in the U.S. economy. It is a broad measure

that reflects the returns to real estate and small business capital as well as corporate capital.

…

The effects of regulation do not always fall exclusively or primarily on the allocation of

capital. When regulation primarily and directly affects private consumption (e.g., through higher

consumer prices for goods and services), a lower discount rate is appropriate. The alternative

most often used is sometimes called the social rate of time preference. This simply means the

rate at which “society” discounts future consumption flows to their present value. If we take the

rate that the average saver uses to discount future consumption as our measure of the social rate

of time preference, then the real rate of return on long-term government debt may provide a fair

approximation. Over the last thirty years, this rate has averaged around 3 percent in real terms on

a pre-tax basis. For example, the yield on 10-year Treasury notes has averaged 8.1 percent since

1973 while the average annual rate of change in the CPI over this period has been 5.0 percent,

implying a real 10-year rate of 3.1 percent.For regulatory analysis, you should provide estimates of net benefits using both 3 percent

and 7 percent. An example of this approach is EPA’s analysis of its 1998 rule setting both

effluent limits for wastewater discharges and air toxic emission limits for pulp and paper mills.

In this analysis, EPA developed its present-value estimates using real discount rates of 3 and 7

percent applied to benefit and cost streams that extended forward for 30 years. You should

present a similar analysis in your own work.

I have been in close contact with various people who go through all these releases with a fine-tooth comb, and none of us has yet found an estimate of what the SCC would be, at a 7 percent discount rate, even though that is part of the default regulatory requirement.

Also, if you want to argue that we should use Treasury yields, OK–tell me what the yield is on a (hypothetical) 75-year Treasury bond, because that’s (at least) the time horizon involved in climate change regulations and taxes. If we interpolate from the existing Treasury yield curve, it’s not obvious what the yield should be, but one could argue it’s more than 3 percent–especially if we think we’ll get out of the second Great Depression by 2050.

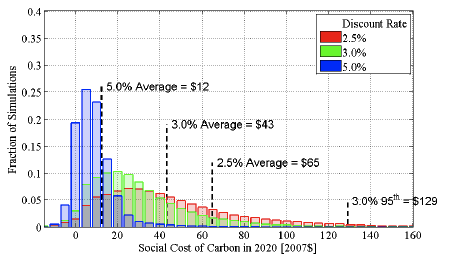

UPDATE: The last time I posted on this, somebody in the comments said the SCC couldn’t possibly be negative, regardless of the discount rate. Well, look at this figure from page 14 of the May 2013 update to the White House Working Group’s estimate:

At just a 5% discount rate, the “average” SCC is reported as $12/ton. (And that’s for a ton of emissions in 2020, when the SCC will be higher than it is right now.) But if you look at those blue bars, you’ll see that this is because around 20% or so of the computer runs (at this discount rate) yield a SCC that is nonpositive, but which is counterbalanced by the 80% or so runs that have a positive SCC.

As you can see from the distribution of the green and red bars, throwing in a 7% discount rate would result in even more probability weight falling on the $0 or negative scenarios. Would the overall result be negative? I don’t know for sure without seeing the actual annual numbers, but the OMB default rule means that the Working Group should have reported that figure.

Does Whole Life Insurance Inefficiently Mix Two Goals?

[NOTE: The following article originally ran in the June 2013 issue of the Lara-Murphy Report.–RPM]

Does Whole Life Insurance Inefficiently Mix Two Goals?

by Robert P. Murphy

June 2013

In last month’s issue of the Lara-Murphy Report, I explained my own history with Nelson Nash’s Infinite Banking Concept (IBC). IBC allows you to “become your own banker” by funding large purchases through the use of a properly designed dividend-paying whole life insurance policy. I received a lot of good feedback on the article, but also some criticism. In this month’s issue, I want to specifically respond to the critique posted at the blog “Libertarian Investments.”

Summarizing the Critique

The post ran on June 15, 2013, and was titled, “Infinite Banking Concept or Whole Life Insurance.” Let me quote extensively from the post to accurately convey the author’s perspective:

I have never been a fan of whole life insurance. I have always thought of it as a rip off. If you need life insurance, then get term life insurance. You don’t need to mix two things – life insurance and savings/ investments.

…

I can possibly see benefits to buying whole life insurance for a limited number of people. Generally, I still think it is a scam though. There are salesmen who solicit people to buy whole life insurance policies and these salesmen make a living doing this. This doesn’t automatically make it bad, but I suppose it is due to the nature of the business.

I understand there are salespeople and there is marketing in almost every industry. A car salesman makes a commission, but it doesn’t mean that you are getting ripped off when you buy a car. But there are significant differences. You can go online and get a quote for a term life insurance policy without speaking to anyone. They will call you up and verify your information. They may send out a nurse to you to get a physical to make sure you are healthy. If you are young and healthy, you can get term life insurance that is quite inexpensive. There really is no need for a salesman…

Whole life insurance is mixing things. It is mixing life insurance and your savings and investments. For this reason, it makes the numbers rather confusing. I think the industry likes it this way. But we all know there is no free lunch (at least those reading this blog who call themselves Austrians). There is no magical rate of return just because it is a whole life policy. There are no special interest rates to be earned. The salesman’s commission has to come from the payments you are making on your policy (so to speak).

…

I am still not really seeing any advantages to the IBC, other than it being a good plan for those who lack discipline in their financial life. If anything, IBC would be a disadvantage because of the commissions and fees that you are handing over, when you can simply do much of it on your own and cutting out the middle man (the salesperson).

In conclusion, I might have to read more of Robert Murphy on this subject. I respect him and I want to make sure there is not something that I am overlooking. But for right now, I would suggest sticking with a good term policy if you need life insurance. Take care of your saving and investing separately. I don’t see a need to combine the two together and confuse them. That is how you get ripped off. [Bold added.]

Thus we see that this critique (the tone of which was far more polite than I lot of the commentary on whole life) falls back on the standard “buy term and invest the difference” recommendation. I specifically addressed that in the last issue, in the context of Dave Ramsey’s critique of whole life, and I’ll end up reiterating some of the key points here in this article.

But the reason I chose to address this specific critique is the writer’s emphasis on the notion that whole life insurance is “mixing” the two different goals of (a) pure life insurance and (b) wealth accumulation. At first this sounds like a very damning point, but as I hope to show, if we moved the context to another arena, it would be an irrelevant bit of trivia.

An Analogy With Real Estate

Most people are familiar with real estate (because we all have to live somewhere), so this is an easy context in which to make my point. Imagine the following hypothetical conversation between two financial advisors:

SALLY: I was talking to a couple last week, who currently live in a small apartment but are now expecting to have a baby. The husband has a stable job, they have a diversified portfolio of financial assets that are on target for their retirement, they hate moving, the husband wants to get a dog, and the wife wants to start a garden. I told them that given all these factors, and especially with the tax deduction on mortgage interest, they should seriously consider buying a house, instead of moving to another apartment.

DAVE: What are you nuts?! Everybody knows home-buying is a scam. For one thing, there are real estate agents who take a nice commission on both ends. But more important, if you buy a house to live in, you are mixing two things: your purchase of shelter services, with real estate investing. There are houses that can be rented; your monthly payment to a landlord is much less than what you’d pay on a conventional mortgage for the same property. If you really want to invest in real estate, then take the money you save on your monthly house payment and go put it in a REIT or something. And last thing: Don’t bother running numbers trying to show me clients who did OK by buying their home, because at any moment Congress could take away the tax deduction and oops, there goes your whole case for why somebody should buy instead of rent. Only suckers own the house in which they live, especially for the poor fools who end up selling their house soon after they buy it. I always tell my clients to rent.

Now let me ask: Does anyone think our hypothetical financial advisor Dave above just “proved” that it’s always a bad financial move to buy a home? Yes, sometimes it’s a bad decision—if someone’s job causes him to constantly travel, or to relocate every other year, then renting probably makes more sense. But we certainly can’t discredit “buying a home” with the observation that it’s mixing the two goals of shelter services and real estate investing.

Notice two that there’s nothing contrived or needlessly complicated about the benefits of buying a home. It’s a straightforward transaction, but if we are to understand its costs and benefits, we need to realize that it’s not just a purchase that provides a flow of shelter services—it can also serve as collateral for loans, it can be bequeathed to heirs, and if the financial picture really changes it can be sold, even before the mortgage is paid off (so long as the owner isn’t underwater). And yes, people need to take the tax code into account when making a major decision such as buying a home, including the deductibility of mortgage interest as well as the (limited) exemption on capital gains for owner-occupied houses. To say this doesn’t concede that “home buying is based on the tax code,” it just reflects common sense.

Let me end this analogy with the final observation: One of the strongest motivations to own one’s house is the peace of mind and security from knowing that, well, you own the place in which you live. If you rent, you had better not get too attached to the place, because you might not be allowed to renew the contract (at least on the same terms) indefinitely. You simply can’t exactly replicate “buying a home” through “rent a comparable property and invest the difference in real estate.” Ultimately, the straightforward transaction of buying a house has certain attributes that are unavailable through other financial strategies.

Back to Life Insurance

The situation is similar when it comes to whole life insurance. It is a straightforward financial instrument: You sign a contract with the insurance company, promising to pay a (level) premium for a specified length of time. In exchange, the insurance company promises to pay a specified amount either when you die, or when you reach a (high) age, such as 121 in recently issued policies. That is the essence of what a whole life insurance policy is; it effectively provides “pure life insurance” for your whole life (since most people are going to die before hitting the maturity date). But in addition, because of its nature, it has other features as well. You can borrow against it, you can specify an heir to receive the death payment, and if the financial picture changes drastically, you can “surrender” the policy and receive what is effectively the “equity” you had built up inside of it thus far.

Now of course, if someone is going to seriously consider buying a large whole life insurance policy, then he or she needs to consider all of the tax ramifications, because there are plenty of advantages with the current code. So long as a policy has not become a “modified endowment contract” or “MEC” (and reputable insurers and agents will ensure that doesn’t happen), then the policyholder is not taxed on the accumulating cash value, policy loans have no tax implications, and dividends can be withdrawn up to the point of the “cost basis” in the policy without tax. (And of course, whether the policy is a MEC or not, the death benefit payment is itself an income-tax free event for the recipient.) None of this is to suggest that whole life is a creature of the tax code, it just means a person’s lifetime financial plan must consider the tax advantages when evaluating whole life as an option.

For many people, particularly those who use whole life in the context of the broader IBC philosophy, its fundamental virtue is control over one’s money. Usually IBC practitioners talk about “control” in the context of being able to access (through loans, dividends, or partial surrenders) the wealth embodied in a policy at any point, without penalties, unlike traditional tax-qualified investment plans.

However, in our present context, whole life’s superior “control” comes in the form of having guaranteed life insurance coverage. If you just buy a term policy, you may not be able to renew it when it expires. You are in the same situation as the renter, who might get kicked out of “his” house by the landlord, because it wasn’t really “his” house to begin with. With a whole life policy, that particular worry is gone.

Conclusion

In closing, let me be clear that I am not saying that buying a house right now in 2013, especially by going to a commercial bank and taking out a 30-year mortgage, is a great idea. In our other writings, Carlos and I have explained that we think Ben Bernanke’s policies have set the U.S. up for another crash, and that taking out loans from commercial banks is itself a dubious practice that contributes to our inflation problem.

All I have done in this article is show that conventional financial discussions, which routinely dismiss whole life on the grounds that it “mixes two goals,” would likewise end up telling people that they should always rent apartments. We can see how absurd such a categorical statement would be, and we can see all the ways that their hypothetical analysis was not actually apples-to-apples.

If you can understand what I mean with respect to buying a home, then you can at least appreciate my claim that an analogous thing has happened with whole life insurance. When people like Dave Ramsey or the blogger quoted above say they are making a fair comparison by buying a term policy, they are simply wrong. You can’t replicate the flow of benefits from a whole life policy by buying term.

To point this out doesn’t, of course, mean whole life is for everyone. For example, a young couple with very little discretionary income and a bunch of young children will need a large term policy, and depending on the numbers it’s possible they have to wait a few years before even thinking about taking out even a modest whole life policy. I have no problem if the financial gurus simply caution people that whole life isn’t for everyone. Yet they go much further than this, and say that only a fool would buy a whole life policy. Such over-the-top condemnations don’t even begin to make a valid comparison, as I’ve tried to show in this article.

Krugman Is Very Influential–Except When It Comes to Economic Policy

Way way way back on July 3, Krugman wrote a post with the sarcastic title “Nobody Pays Any Attention to What I Say.” Here’s the gist of it:

Or that’s what people keep telling me. Actually, one of the odd but revealing things about modern conservatives is the way they alternate between paranoia about the vast left-wing conspiracy and insistence that people who disagree with them are part of a tiny fringe with no real following…

So, on the general principle that if I am not for myself, who will be for me: that left-wing rag the Wall Street Journal has a new assessment, based on some supposedly objective criteria (but not including Twitter followers) of the most influential business thinkers. They see a big change since the last time they did this, five years ago…This time, the top thinkers are:

1.Paul Krugman

2. Joseph Stiglitz

3. Bill Gates

4. Michael Porter

5. Thomas Friedman

6. Eric Schmidt

7. Richard Branson

8. Malcolm Gladwell

9. Robert Reich

10. Jack Welch

11. Muhammad Yunus

12. Niall Ferguson

13. Michael Dell

14. Howard Gardner

15. Jimmy Wales…

Something else…is that the list isn’t just heavy on economists; it’s heavy on liberal economists. I don’t think that’s an accident, and I don’t think it’s purely political. The fact is that in an era of markets gone massively bad, conservative economists don’t have much to offer except excuses.

At the time, I thought this was an odd post. Perhaps the single person on Earth most responsible for the idea that nobody listens to Paul Krugman is…Paul Krugman himself. Think of how he always laments about the Very Serious People listening to the allegedly discredited R&R, John Taylor, Allan Meltzer, even though they’ve “been totally wrong about everything” since the crisis began, etc.

I was going to go find some of these recent posts, to give an example of what I mean, but fortunately today (July 5, a full 48 hours after the above), Krugman writes:

We had what felt like an epic intellectual debate over austerity economics, which ended, insofar as such debates ever end, with a stunning victory for the anti-austerity side — and hardly anything changed in the real world. Meanwhile, the pain caucus has found a new target, inventing dubious reasons for monetary tightening. And mass unemployment goes on.

So how does this end? Here’s a depressing thought: maybe it doesn’t.

OK great. When the depression fails to end, according to the July 3 post, I am going to blame it on the highly influential liberal economists like Krugman, Stiglitz, and Reich. If Krugman then comes back and says, “No no no, nobody listens to what I say, that’s why we are mired in depression,” we can then point out his odd and revealing alternation between smug pride over his influence, and paranoia about people ignoring him.

The Fed’s Equity

Given the recent rise in Treasury yields, I asked Caitlin Long (an Austrian at Morgan Stanley) if they had reevaluated the Fed’s equity. She said (and gave me permission to relay to you folks) that as of mid-June, just over half of the mark-to-market cushion remained. That means an additional 80bps shift in the yield curve from June 15 levels would wipe out the remaining mark-to-market cushion.

Rental Car Gas Options

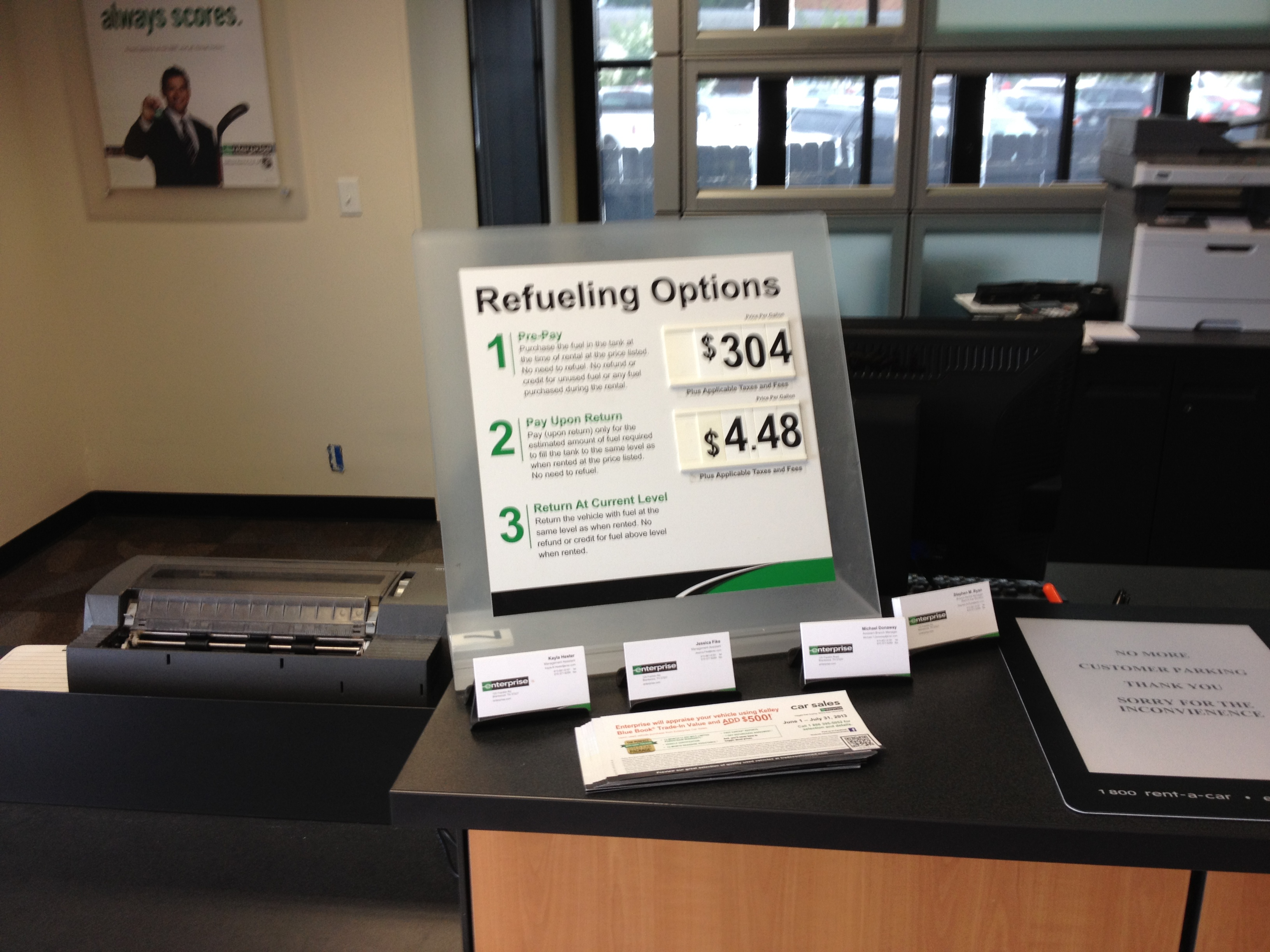

What’s the story with these options? I took a photo at my recent trip to a car rental place:

So if you read the fine print–or if you just use common sense and figure the car rental place isn’t going to sell you gas at below-market prices–then it looks like pre-paying for a “full tank of gas” at an apparently cheap price, only works because they’re actually charging you the price x tank capacity when obviously not everybody is going to return the vehicle as it stalls from running out of gas.

However, when I was explaining this to my business partner on a recent road trip, he was arguing with me, saying that’s not the deal the person at the counter explained to him. I called up the place (we were driving back), and made sure the employee on the phone was quite explicit that they were not charging us for the full tank, but only for the difference (and at the apparently generous price).

Indeed, recently when we rented from the same place, the employee said (as we walked around the vehicle looking for scratches), “Yeah, we won’t charge you for the full tank like they do at the airport.”

So what’s going on? Have we discovered a particular location of this national chain, where the employees are either (a) very generous, (b) ignorant of company policy, or (c) pathological liars? In case it helps explain this post: I was not the one renting the car, so I never really inspected the final bill with a microscope. So I don’t know whether they were actually charging us for the full tank or not.

Another False Victory Claimed Against A Priori Theory

Hans Hoppe (as well as many other living Rothbardians) argues that the purpose of property rights is to resolve disputes over scarce resources. (It is through this channel that Stephan Kinsella argues against the existence of legitimate “intellectual property” rights, since IP isn’t scarce.)

Gene Callahan doesn’t like Hoppe’s claim. Today he writes:

Of course, when property rights are agreed upon, there won’t be disputes — but that really says nothing more than where there is agreement, there is no dispute!

But property rights are often the very source of disputes. Reading Bailyn’s account of the English settlement of Massachusetts drives that point home with great force. In understanding the human world, history trumps theory! [Bold added.]

Yet hold on a second. Bailyn’s account of the English settlement of Massachusetts contributes absolutely nothing to Gene’s point. Hoppe (and Kinsella) obviously doesn’t think the world is free from disagreements over the use of scarce items.

In fact, I’m sure that Gene would agree with me, since on June 14, 2011, he wrote a whole blog post criticizing Hoppe’s position, relying purely on a Socratic dialog. No specific historical experience necessary; Gene’s point (whether you think it silly or brilliant) is obvious enough once it is mentioned.

Last Chance: Sign up for “Adventures in Energy Economics”

One last plug: In a couple of hours we start the first class of my Mises Academy online class on energy economics.

Recent Comments