Potpourri

==> Mark Spitznagel is the subject of this DealB%k post. (Recall that I was a consultant on Spitznagel’s new book The Dao of Capital.)

==> Indian Central banker Rajan is wary of ultra-low interest rates.

==> I didn’t set this up, but here’s where you can get all of your Macho Man Murphy memorabilia.

==> Steve Mariotti details the rescue of Mises’ papers from the Soviets.

==> According to this empirical research, economists are not hot by any stretch, but we’re more attractive than you would expect, given our high intelligence.

==> Berkshire Hathaway’s Charles Munger (a billionaire himself) says Americans should thank God for the bailout of the banks, but that the little guy needs to suck it up and not take government handouts. (Really.) I actually have to give a hat tip to Paul Krugman on this one (don’t have the link to his post on it).

SHOCKER: Price Controls Lead to Shortages in Venezuela

The news is rife with stories of the awful shortages of basic essentials in Venezuela. For example, the BBC World Service did an extended report, and the following comes from a Guardian article:

It’s the rainy season in Venezuela and Pedro Rodríguez has had to battle upturned manhole lids, flooded avenues and infernal traffic jams in his quest for sugar, oil and milk in Caracas.

…

In Avenida Victoria, a low-income sector of Caracas, Zeneida Caballero complains about waiting in endless queues for a sack of low-quality rice. “It fills me with rage to have to spend the one free day I have wasting my time for a bag of rice,” she says. “I end up paying more at the re-sellers. In the end, all these price controls proved useless.”In 2008, when there was another serious wave of food scarcity, most people blamed shop owners for hoarding food as a mechanism to exert pressure on the government’s price controls, a measure that former president Hugo Chávez adopted as part of his self-styled socialist revolution.

This time, however, food shortages have gone on for almost a year and certain items long gone from the shelves are hitting a particular nerve with Venezuelans. Toilet paper, rice, coffee, and cornflour, used to make arepas, Venezuela’s national dish, have become emblematic of more than just an economic crisis.

Although people often use the phrase merely for rhetorical points, this episode really is Econ 101. The price controls instituted under former president Chavez are the ultimate source of the shortages. Naturally, Chavez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro, blames everything on a “wider plan concocted by the CIA to destabilise his government,” according to the Guardian piece.

As any intro economics textbook explains, when the government sets the price of a good below the market-clearing level, you get a shortage. That is, buyers want more units of the good than sellers want to provide. This is playing out in literally textbook fashion in Venezuela.

As a final note, this isn’t Monday morning quarterbacking on my part. Back when Chavez devalued the currency and ramped up price controls, I said it would lead to shortages. Here’s an excerpt from an article I wrote back in February 2010:

“The bourgeois are already talking about how all prices are going to double and they’re closing their businesses to raise price,” Chavez said on state-controlled television. “People, don’t let them rob you, denounce it, and I’m capable of taking over that business.”

True to his word, Chavez sent troops into retail shops to inspect prices. Economists know the effect this will have. Chavez will find that no amount of populist rhetoric or military might can overturn the laws of economics.

By definition, the market-clearing or equilibrium price is the one that equates supply and demand. By using soldiers to intimidate businesses into keeping their prices below the (new) market-clearing level, Chavez will cause demand to exceed supply, creating a shortage. Venezuelans will find that the items in question will simply disappear from the shelves, and will be available only in the black market.

Political rulers can violate the laws of morality, but they can’t overturn the laws of economics. If Venezuelans want to once again readily obtain toilet paper and food, they should demand that their government allow the market to function.

A Tale of Two Krugmans

When it comes to investors worrying about the federal government paying its debts, Krugman says it is the best of times, and the worst of times, depending on whether it’s due to big-spending liberal Democrats (best of times) or budget-slashing conservative Republicans (worst of times).

When writing a somewhat technical piece in November 2012 about the power of bond vigilantes to suddenly realize the debt was a problem, Krugman said that even if this happened (which he doubted), it would rescue the economy from the liquidity trap first. To be sure I’m not misquoting him, I’ll post from a follow-up blog where Krugman clarified his position:

A skeptical correspondent asks whether I really truly believe what I’m saying in my post about how an attack by the bond vigilantes is actually expansionary when you have your own floating currency. How does this jibe with the experience of the Asian financial crisis of the 1980s, he asks? And do I really believe that Japan would be better off if markets became less confident in the value of its bonds?

Good questions — but ones that I and others have already answered.

On financial crises past: the key question is whether you have large debt denominated in foreign currency…

The point, of course, is that America doesn’t have a lot of foreign-currency debt. Neither does Japan — which is why I would say yes, reduced confidence in Japanese bonds would actually help their economy.Right now, as I’ve written in the past, the collision of deflation with the zero lower bound means that Japan actually offers investors a higher real interest rate than they can get in other advanced countries. The result is a strong yen that is really hurting Japanese manufacturing. Some loss of faith in those Japanese bonds, whether default risk or fear of higher inflation, would be a blessing. [Bold added.]

Everyone got that? As of last November, a loss of faith in Japanese (and American) government bonds, even if due to fear of default, would be a blessing.

Well then, you would think Krugman would be excited by the prospect of the Republicans causing fear of default and thus blessing the economy, right? Of course not. Here’s a good example of Krugman’s commentary on the most recent “debt crisis,” this one from September 25, 2013:

Add me to the chorus of those puzzled by the lack of market alarm over the possibility of U.S. default, induced by failure to raise the debt ceiling. The best story I’ve heard came from a government official who put it something like this: “Business types come to Washington, and they talk to Boehner, or Paul Ryan, or Eric Cantor – all of whom are very hard line, but not insane. So they go home reassured. What they don’t realize is that those guys aren’t in control, and that they’re running scared of a large faction of the party that is indeed insane.”

That makes sense to me; if most political reporters are still in denial over the real state of affairs, one can imagine that businesspeople are having an even harder time realizing the extent to which the inmates have taken over the asylum.

But suppose that markets were giving the possibility of default the attention it deserves; how should they be reacting? That’s not actually all that obvious, at least as far as interest rates are concerned.

What everyone stresses is that U.S. government debt, until now regarded as the ultimate safe asset, suddenly becomes not so safe. That could drive up short-term interest rates, at least a bit, because T-bills could start to trade at a discount relative to cash. Although maybe not. Is there a reason the Fed can’t serve as bond buyer of last resort, standing ready to buy T-bills at par, so they remain fully liquid?

Meanwhile, what about long-term interest rates? A lot of people seem to assume that they’ll go up, because who’ll buy debt that might face delays in payment? But see above. Meanwhile, think about the macro impact. Here’s federal receipts and outlays:

[Chart…]

If the feds are forced to slash spending, one way or another (and probably semi-randomly) to match receipts, that’s about $600 billion in cuts at an annual rate, or 4 percent of GDP. That’s a huge case of unintended austerity, quite aside from the disruptions, surely enough to push us back into recession if it lasts for any length of time.

And a double-dip recession would, in turn, push back the date of Fed rate increases far into the future, which would normally cause a big drop in long-term rates.

So I’m not at all sure that we’re looking at an interest rate spike; maybe even the opposite.

But for sure we should be looking at a plunging dollar, and probably carnage in the stock market too.

I quoted the entire post above, so there’s no doubts about me taking him out of context.

As just about always with Krugman, he can pull the shark repellant from his utility belt to get out of this particular jam. He can make some assumptions about what government spending would do if the bond vigilantes attacked because of large debts versus attacked because the Republicans refused to raise the debt ceiling, blah blah blah. But the crucial point is that back in November, when he wanted to pooh-pooh the people warning about investors suddenly doubting the US government’s ability to pay off its bonds, Krugman didn’t say one word about the government having to slash spending in such a scenario. No, it was all about the counterintuitive result that our economy would be helped by such an outcome.

Now, when he wants to attack Republicans for threatening a debt default in the fight over ObamaCare, Krugman doesn’t even devote a sentence to the technical paper he showcased for his readers back in November, explaining how Krugman thinks about a debt default in a modern economy with its own fiat-denominated debts. Instead, he focuses on the attendant slash in spending and how this will cause a double dip recession and “carnage.”

Sometimes the newcomer is confused by the apparent randomness in Krugman’s posts, about when he makes certain assumptions and when he makes others, and when he focuses on effect X while at other times he focuses on effect Y. But there actually is a pattern… I’ll leave it as an exercise to the reader.

Nick Rowe: It’s the End of NK Models as We Know Them, and I Feel Fine

[UPDATE: See Nick Rowe’s comments in the post for further clarification, plus I tweaked a few things in the post itself in response to his comments.–RPM]

In a previous post, I explained that the academically respectable, formal New Keynesian model of the economy was collapsing before our very eyes. I mentioned that Nick Rowe was fully aware of–indeed was a chief contributor to–this collapse, and yet he didn’t think it a very big deal. Now I realize that the two go hand in hand: Precisely because Nick has the temperament of Confucius, he can afford to be completely frank about the state of mainstream macro theory. It’s not good.

In this recent post, Nick walks through some of the deep problems with various models, and in doing he gives his take on John Cochrane’s recent critique of liquidity trap models. Here’s Nick:

What John Cochrane is saying is that inflation is indeterminate in the Neo-Wicksellian/New Keynesian model, even if you just assume that the output gap asymptotes to zero.

…

John Cochrane proposes an alternative solution to the same set of New Keynesian equations…John Cochrane is not (as I read him) saying his solution is the right one. He is saying it is no less right than the standard solution.

Both those solutions are consistent with the IS curve and Phillips curve of the New Keynesian model. Both are mathematically correct. Neither of these solutions is “pathological” in the sense of causing inflation to go to plus or minus infinity. Both solutions would be equally stable or unstable in the sense of staying or not staying on that path if the central bank threatened to respond if they strayed from the equilibrium path. And those are just two solutions from an infinite number of solutions. And there is nothing in the model itself that tells us which of those solutions is the “right” one. There are multiple equilibria.

Now there are some models with multiple equilibria where the modeller knew there were multiple equilibria right from the start, and proudly called the readers’ attention to the fact that the model had multiple equilibria, because he thought it was an important and desirable feature of the model that reflected something about the world. The Diamond-Dybvig model of bank runs (which has two equilibria, one with a bank run and one without) is like that.

But the New Keynesian model is not like that. Nobody said “Hey look! I’ve just built this New Keynesian model which is a really neat model because it has an infinite number of equilibria, and so it can explain why sometimes we get recessions and sometimes we get booms, and those recessions and booms just happen; they aren’t caused by anything at all, except animal spirits, or sunspots! And you can get totally different responses to exactly the same shocks and exactly the same monetary policy responses to those shocks, just because!” The New Keynesian model was never taught that way. It was taught as saying that recessions and booms and inflation and deflation were caused by bad monetary policy which didn’t or couldn’t respond to shocks correctly and quickly enough.

How should we respond to all this?

…and then Nick lists some options.

Let me just shine the spotlight on Nick and say that this is really important, folks. Unfortunately, this is analogous to the Great Debt Debate, when a grumpy economist (Don Boudreaux then, John Cochrane now) challenged something very fundamentally that Krugman et al. have been saying throughout the crisis. Nick (then and now) joined in, with his own analogies and idiosyncratic way of putting it. However, I’m afraid that because Nick is so immersed in the literature, that only professional economists will really get what he’s saying. The problem there is that professional economists are the last people on earth to judge a dispute on whether a big chunk of professional economics has been spinning its wheels for the last few decades.

Some open questions that I would love to resolve if I had tenure:

1) Is Nick right that the standard New Keynesian model predicts that a sudden an expected and large drop in future government spending can restore full employment in the present? If so, isn’t that kind of important? If both sides of the fiscal policy debate actually believed their rhetoric, this should solve everything: We cut announce cuts to government spending for next fiscal year and fix the debt problem, and we put everyone back to work right away.

2) Krugman has been claiming with a large degree of confidence that Keynesian models show that the normal laws of economics are turned upside down once we hit the zero lower bound. Cochrane and Nick Rowe are claiming that actually, if you write out the equations of a standard New Keynesian model, there are an infinite of equilibria. Yes, some behave the way Krugman says, but others behave the way Fama says. (Furthermore, Cochrane claims that the Krugman-esque equilibria have some really weird properties, such as things blowing up when you introduce epsilon of price stickiness, whereas the Fama-esque equilibria don’t blow up. But Nick didn’t confirm that aspect of Cohrane’s post.) So, is there a contradiction here? It’s true that Krugman doesn’t usually call himself a New Keynesian, but then again when he took Casey Mulligan out to the woodshed he was happy to lump “old or new, it doesn’t matter” into the same category of Keynesian models against Mulligan’s (alleged) ignorance.

3) Both Cochrane and Krugman (sic) have said that the standard Keynesian models (at least if we are looking at “liquidity trap-esque” equilibria) imply large price deflation in the kind of slump we’ve had. Krugman has dealt with that problem by adding what (to me) is analogous to Einstein’s cosmological constant: Krugman sees that prices aren’t falling as fast as the model originally predicted, so he plugs in an assumption that wages can’t fall fast. So, is it better to say–for economists who pride themselves on being good empiricists–that we should rule out the liquidity trap equilibria as being unfaithful to the data?

Unlike with the Great Debt Debate, I don’t think I can get sucked too much into this one, at least not until I clean off my consulting plate and that will take at least a month. So for those of you who can actually understand technical macro papers, do it for the children!

The Most Important Failure to Communicate Ever

I was reading the story of Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus, which leads to the famous John 3:16 verse (which you’ll see cited at baseball games etc.). But on this reading I was struck by how Jesus and Nicodemus barely seem to be talking to each other; each response seems to have little do with what came before it:

1 There was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews. 2 This man came to Jesus by night and said to Him, “Rabbi, we know that You are a teacher come from God; for no one can do these signs that You do unless God is with him.”

3 Jesus answered and said to him, “Most assuredly, I say to you, unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

4 Nicodemus said to Him, “How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother’s womb and be born?”

5 Jesus answered, “Most assuredly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God. 6 That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. 7 Do not marvel that I said to you, ‘You must be born again.’ 8 The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but cannot tell where it comes from and where it goes. So is everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

9 Nicodemus answered and said to Him, “How can these things be?”

10 Jesus answered and said to him, “Are you the teacher of Israel, and do not know these things? 11 Most assuredly, I say to you, We speak what We know and testify what We have seen, and you do not receive Our witness. 12 If I have told you earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if I tell you heavenly things? 13 No one has ascended to heaven but He who came down from heaven, that is, the Son of Man who is in heaven.[a] 14 And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up, 15 that whoever believes in Him should not perish but[b] have eternal life. 16 For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life. 17 For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through Him might be saved.

18 “He who believes in Him is not condemned; but he who does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God. 19 And this is the condemnation, that the light has come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. 20 For everyone practicing evil hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his deeds should be exposed. 21 But he who does the truth comes to the light, that his deeds may be clearly seen, that they have been done in God.”

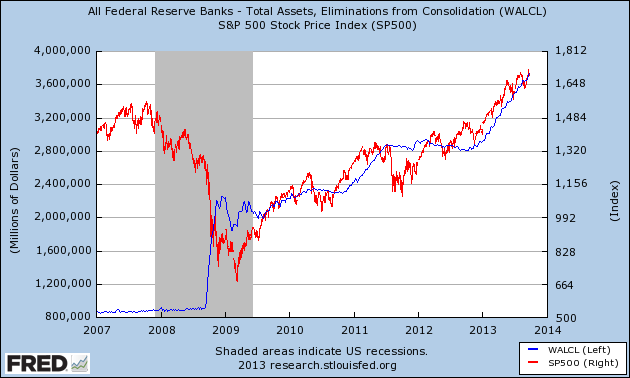

Yes Virginia, Bernanke Is Indeed Driving the Stock Market

In a recent post where I linked to Peter Klein’s commentary on the non-taper, at least one person challenged the idea that the so-called recovery was being fueled completely by Fed inflation. Well, check out the following chart, which plots the Fed’s total assets against the S&P500 index:

Recent Comments