Economics Laureates in Favor of Raising the Minimum Wage

[UPDATE below.]

The Economic Policy Institute has released a letter signed by 75 economists–including 7 winners of the Nobel (Memorial) Prize in economics–calling for the federal government to raise the national minimum wage from its current level of $7.25 to $10.10 by 2016. In this post I want to explain how this is possible, and why I remain wedded to the (literally) textbook discussion of minimum wages.

The obvious downside of raising the minimum wage is that it would cause unemployment among low-skilled workers, the very people allegedly being helped. Yet according to the EPI letter, the evidence shows that previous increases in the minimum wage have had “little or no negative effect on the employment of minimum wage workers, even during times of weakness in the labor market.”

If you want to see where these economists are coming from, try this survey article. It documents how the consensus through the 1990s used to be just what we all learned (and taught, for some of us) in Intro: Raising the minimum wage reduces the quantity demanded for low-skilled workers, thereby reducing job opportunities.

Yet from the 1990s onward, the literature began shifting. From today’s vantage point, the new consensus is apparently that modest increases in the minimum wage have little impact on employment. Hence, you have progressive economists clamoring for a hike, who say that the critics relying on “textbook economics” haven’t kept up with the cutting-edge literature.

I have several responses to these developments:

(1) Even among the studies that conclude a hike in the minimum wage will have little discernible impact, the outcome is couched as a “modest” hike. I have seen studies say things like “a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage will have such and such effect.” Yet disregarding price inflation through 2016, the EPI letter calls for a 39% increase! I could be mistaken, but I don’t think there exists a single academic study concluding that a 39% hike in the minimum wage would have no appreciable effect on employment. Thus, even if we stipulated all of the recent empirical studies as gospel, the 75 economists have no basis for their recommended policy. At best they should be arguing that, say, a hike from the current $7.25 to $8 per hour (and thereafter adjusted for price inflation) would not measurably hurt employment.

(2) Again, even taking the new generation of studies at face value, they overlook a major drawback to the progressive goal: The studies look at the absolute growth in employment, rather than the unemployment rate, among low-skill workers. So even if it’s true that, say, a Burger King franchise will hire roughly the same number of teenagers between now and 2020 as it otherwise would have, it might not be the same group of teenagers getting jobs. Rather, at the $7.25 level there will be lower-skilled applicants cycling through, with a high turnover rate as the store manager tries to find the few decent workers in the bunch. At the higher rate of $10.10 per hour, higher-skilled kids (perhaps those from affluent families who are home from college) will enter the mix in greater numbers. The manager will be pickier on the front end in giving somebody a bite at the apple, and there will be less turnover. (Note that this isn’t merely hypothetical; the studies finding “no effect” often cite “lower job turnover” as an explanation for how the firm responds.) Thus, even taking the studies at face value, it is entirely possible that there are a bunch of people with low skills who now can’t get a job, who otherwise would have been able to. They are merely being displaced by higher skilled workers who otherwise would not have been interested in a position paying so little.

(3) Finally, I am not convinced that we should take these new studies at face value. I admit that I have not studied them in depth, but if you look at the discussion in the survey article I mentioned above, here’s what it sounds like: You can take all of the adjacent counties in the country for which you have continuous data over a long period (such as 16 years), where the applicable minimum wage is occasionally different in each county (because they fall in different states). If you “naively” run a regression on this dataset, then the classical consensus emerges: It does indeed seem that a higher minimum wage is associated with a slowdown in the growth of employment. However, this could be a spurious result, because states with high population growth might just so happen to also match the federal minimum wage, rather than setting a higher state level. To correct for this, the newer studies introduced a regional dummy variable into the regression analysis, at which point the negative effect of the minimum wage almost disappears.

If indeed what I just described is what’s going on, then that seems ludicrous. The point of matching contiguous counties is to isolate all other relevant variables, except for the applicable minimum wage. You can’t use the weather (one of the explanations given in the survey article to explain the flaw in the original studies, which did not correct for geography) to explain why people would flock to one county versus the adjacent one.

To repeat, I admit I haven’t personally vetted the individual articles and looked at their t-statistics, but I am very suspicious that their procedure is illegitimately dampening the very real result–which accords with common sense–that raising the price of low-skill labor will cause employers to hire fewer such workers. In short, demand curves slope downward.

UPDATE: At the urging of Ken B. in the comments, I dug up a previous post where I walked through my final point on the contiguous county pairs. Here it is.

Potpourri

==> At Mises Canada I publicize the fact that Alan Greenspan’s PhD dissertation apparently discussed a housing bubble. (Was this common knowledge? Thanks to Frank C. for tipping me off.)

==> Speaking of Mises Canada, its president–Redmond Weissenberger–is hosting a show called “Better Red Than Dead.” He’s had me on, as well as Doug French, Jeff Tucker, Dave Howden, and other names you might know.

==> An interesting symposium of articles at Liberty Fund on Mises’ The Theory of Money and Credit. Larry White (in the lead essay) briefly gives me some pushback on my musings on Bitcoin and the Regression Theorem. This doesn’t end here, Larry!

==> Climate scientist Judith Curry is learning about Hayek from her recent interview with Russ Roberts. Incidentally, I think Curry is a good example of a climate scientist who changed her mind on the climate debate. Or at least, she initially was just a rank and file scientist but over the years has come out more and more against what we are being told is the “settled science.”

==> How to Win a War With Iran? Don’t start it.

==> I used to think the people who put tape over their computer cameras were paranoid, but apparently not.

==> Mises was a feminist before it was cool?

==> I think I blogged about this when I heard the NPR story, but in case you missed it: This was a really interesting case where a police detective explained how they had unwittingly gotten an innocent woman to confess to murder. I know a lot of you aren’t fond of cops, but put aside your hate and just try to understand how it happened. It’s very interesting, as well as chilling. I know when I was a young punk self-described conservative, if someone had confessed to murder I would have had very little sympathy for such a person.

==> How to defeat Fallacy Man.

==> New NYC mayor de Blasio picked the wrong issue when he tried to ban horse-drawn carriages. Now he’s got to deal with Liam Neeson. He may have a small army in the NYPD, but that surely will only buy him a few weeks.

==> Ben Powell totally takes over this panel, such that former MTV “VJ” Kennedy is openly hitting on him by the end. If you’re rushed for time, just watch the last 20 seconds.

“The Tension Between Economics and Religion”

The previous post reminded me that I touched on the familiar antipathy of Christianity to usury in my Lou Church memorial lecture at the Mises Institute in March 2006.

Christianity, Money, and Interest

I met Wayne Walton at the Music City Liberty Fest a few years ago. He is a great guy who has committed himself to educating people about the evils in our current monetary and banking systems, and promoting practical ideas for immediate improvements. Wayne is also an outspoken Christian and so we have that in common, as well.

However, as you will see (e.g. listen to this video), Wayne differs from the standard Austrian/libertarian views on money and banking. He views the problem with the Fed as not merely that it rests on government coercion, but that the very idea of having private institutions issuing money upon which they charge interest is dubious. As the video shows, there are numerous places in Scripture to reinforce Wayne’s interpretation of the proper Judeo-Christian view on this subject.

For a while I have been slightly uncomfortable with some of the rhetoric/arguments used by the “alternative/local currency” movement, but since I agree with these people on so much, I didn’t feel like starting a fight. Yet since this is such a crucial topic, and moreover since I’m debating Bill Still this coming Friday, I thought now was a good time to start a dialog.

Before jumping into my concerns, let me share the following interesting trivia: My dissertation at NYU was in capital and interest theory, and arguably could be described as explaining why interest would exist in a free society. (That’s not how I would have described it, but it’s a fair description nonetheless.) When it was nearing completion, and I was emailing myself a copy so I could print it out at the NYU computer lab, the file size was 666KB. Then, after defending my dissertation and filling out NYU’s exit interview forms (or whatever they called them), I had to fill in bubbles to answer their various questions. The internal code to identify the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Economics Department was–you guessed it–666. Do with that trivia what you will.

Anyway, here are my concerns:

==> Are Wayne and his fans making the age-old distinction between usury and interest, or are those terms interchangeable?

==> Is Wayne saying that in a free society, he predicts that there would be no debt? Or is he saying yes it might happen, but that it would be immoral? Or is he saying that as long as people were free they would be economically on much stronger footing, and so the type of debt that they might voluntarily embrace would be acceptable to him?

==> Here’s a really simple example to get our thinking straight: Suppose Bill owns a new car, and John wants a new car but hasn’t saved up for it. So Bill says to John, “I will give you this car so you can begin driving it immediately, but in 10 years time I want you to pay me back two brand new cars.” Is there anything problematic with such a deal?

==> When Wayne calls for people to issue their own currencies, does he mean at the individual level? That I would issue Bob Notes, and my son would issue notes in his name, and so on? If so, doesn’t that defeat the purpose of using money in the first place? How is that different from barter with credit?

Someone Has to Remind Bryan Caplan That No Such Thing as Utils

One of the issues in Bryan Caplan’s famous “Why I’m Not An Austrian Economist” essay (even though he had been one when he was younger) is the issue of cardinal utility functions. A lot of Rothbardians like to roll their eyes at the mainstream for thinking utility is a cardinal entity that can be measured in principle, whereas Austrians know that preferences are ordinal rankings. In a fit of exasperation, the Rothbardian might exclaim that the standard equilibrium conditions in a typical micro book involve dividing by marginal utility!!

But, as Bryan points out in his essay, such jabs misconstrue what the mainstream economists are doing. They don’t actually take a particular utility function seriously; it merely “represents” ordinal rankings over bundles of goods. There’s no special significance if someone has a certain utility function, because you could represent the same ordinal preferences with any monotonic transformation of that same function. (NB: If you’re doing von Neumann Morgenstern expected utility functions then it can only be a positive affine transformation.) Bryan is right, by the way: When I was a young punk down in Auburn my first year, I made sure everybody knew that I knew a bunch of math from NYU.

Anyway, somewhat apropos, today at EconLog Bryan says that there’s little doubt that a<1, when we model spouses' utility function as U=(Family Income)/(2^a). But Bryan wanted to know: "Where does a typically lie in the real world?” Daniel Kuehn reminded in the comments:

“Where does ‘a’ typically fall in the real world” isn’t a particularly meaningful question because it’s a monotonic transformation. Again I think the private/household good entering a utility function is the better approach.

So then the question is maybe something like what is the marginal rate of substitution between some representative (or bundle of… but I’d have to think about MRS’s of bundles) rivalrous and non-rivalrous goods.

The Krugman/Sumner Showdown–In Layman’s Terms

The blogosphere has been abuzz (though nothing compared to the Great Debt Debate of 2012) with activity centered on whether the year 2013 provided a good test of the economic views of Keynesians like Paul Krugman versus Market Monetarists such as Scott Sumner. These things often get bogged down in technical minutiae. In the present post, therefore, I will crystallize the essence of the dispute in simple terms for the lay reader.

THE KRUGMAN/SUMNER SHOWDOWN

The scene opens with Paul Krugman and Scott Sumner parading around the floor of the arena, surrounded by thousands of cheering and bloodthirsty fans. Both men are adorned with giant peacock feathers.

KRUGMAN: I am the manliest man on the Internet.

SUMNER: No, I am the manliest man on the Internet. That’s what the consensus of my peers tell me, and that’s what it means, after all, for a statement to be true.

KRUGMAN: I propose we settle this by armwrestling.

SUMNER: I’m not sure that that’s the best test, but I accept your challenge.

The men sit at a table and begin the match. At first Krugman appears to have the upper hand, as he pushes Sumner’s arm halfway down to the table surface.

KRUGMAN: It’s not looking good for you, is it Scott? Those Twinkies you’ve been eating seem to be taking their toll.

Sumner then twists his wrist, and pushes Krugman’s hand back toward the starting point. Then he quickly slams it down to the table. Sumner jumps up from the table, lifting his hands in celebration, bowing to the crowd and casting suggestive glances at Matt Yglesias.

KRUGMAN: What? Why is everyone cheering? What’s going on?

Krugman sneaks up behind a triumphant Sumner, winds up, and kicks him squarely in the groin. The Keynesians in the crowd erupt with applause, while the Market Monetarists begin booing.

BRAD DELONG (jogging out from the stands to the middle of the arena): Perhaps I can be of assistance? In my opinion, this has been a draw. The real test of manliness would have checked which gladiator could grow the best beard. Since they both shaved this morning, we just don’t have enough data. I realize the Sumner fans are claiming victory, but damned if I can see why.

NOAH SMITH (who had followed DeLong the whole way to the center of the arena, much as a puppy might): I must concur with Referee DeLong. Now in fairness, it is true that Gladiator Krugman suggested the armwrestling. But I must strongly object to the tactics of Gladiator Sumner. I mean, are you wearing a cup or something, for armwrestling? Who does that? Paul could’ve broken a toe.

SUMNER: Mark Sadowski…go get me my gun.

KRUGMAN (hopping out of the arena on one foot): This is no longer a mere match of manliness. This has now become a test of character!

Curtain.

A Brief Note on the “War on Poverty”

In this country, if you want to spend trillions of dollars on an aspect of social life that you dislike, while not solving the problem, then the best thing to do is have the federal government declare a “war” on it. For example, lots of people are commemorating the 50th anniversary of LBJ’s “War on Poverty.” But even by the defenders’ own logic, the underlying problem has gotten worse.

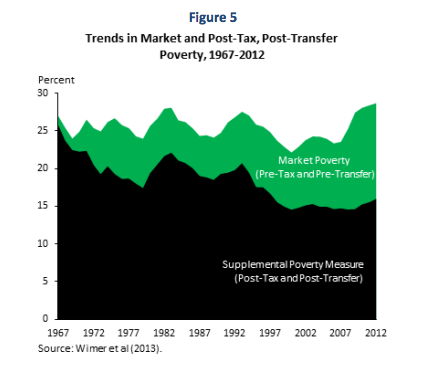

To pick just one prominent example, the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers issued a report that contained the following chart:

Sure, we can quibble with the calculations, but let’s take the chart at face value. What it shows is that the percentage of people in poverty before we look at government measures (i.e. the green) has gone up since 1967, and that this can’t even be blamed on the recent recession (or depression to be more accurate); the number bounced around, but showed no trend toward improvement over the whole period of the “War on Poverty.”

The way the White House (and other defenders of the welfare state, such as Paul Krugman) are trying to spin the above stats, is to look at the black area of the chart, showing that after government taxes and transfer programs, the percentage of people falling below the “poverty line” has gone down. Thus, they declare, the United States government is waging a successful war on poverty.

Yet hang on a second: Surely to actually “win” the War on Poverty would mean that the government could stop spending money, because every household were self-sufficient. The criterion can’t be, “After you account for how much money we’re still throwing at it, the net result is better.”

Switch to an actual military context to see my point. Suppose after Pearl Harbor, the federal government declared war on Japan. Further suppose that 50 years later, U.S. and Japanese forces were still engaged in massive naval battles in the Pacific, and in fact the Japanese had more ships and aircraft than at the start, though they had been pushed back about a third of the distance toward Japan and away from Hawaii. Wouldn’t it be time to declare, “This is not at all working” and sue for peace?

Recent Comments