How Economists Treat Interest

I got an email from a colleague (reprinted with permission):

Dear Bob:

Please settle a bet between me and [another colleague]. One of us maintains that without borrowing and lending, no interest rate could arise. The other of us takes the view that there is always time preference, and this guarantees an interest rate, even in the absence of borrowing and lending (for example, this option has not yet been discovered). Even in this case, one of us maintains, there will be a gap between what workers are paid for goods that are immediately sold, and what workers of equal productivity are paid for goods that don’t come onto the market for a year.

Before I jump in, I want to note that this writer is committed to objectivity; notice that he didn’t say, “I think X, but so-and-so thinks Y, who’s right?” Because then he would have biased me in favor of either the guy I like more, or the guy who is scarier.

But, I will in turn be crafty, and not simply choose which position I endorse. Rather, I will make a series of what I hope are true statements about the way economists should approach these issues, then I will let my colleagues determine who wins the bet.

(1) Economists often make a distinction between an actual market price in a transaction, versus a “hypothetical price” that we imagine must be the case in order to complete our model. For example, suppose we have a group of potential workers and potential employers, and that we know their preferences for leisure/wages and output/money. Every day we can compute what the market-clearing wage is. Now suppose that on a religious holiday, the market-clearing wage is $82/hour, at which price the total quantity supplied and demanded of labor is 0 hours. (Nobody wants to work on this very holy day, and the wage needs to be $82/hour in order to make no employer want to hire even a single hour of labor.) So it’s fine to academically say, “The wage is $82/hour even though no wages are paid,” but on the other hand, in the real world we would have no way of actually knowing that. We couldn’t actually observe what the wage was, so if someone said, “Nope, I don’t see any wages being paid today, so they don’t exist,” then that would be a perfectly defensible statement too.

(2) It is possible for people to earn what everybody would describe as “interest on their invested financial capital” even in situations without explicit lending at a contractual interest rate. For example, suppose it’s December 1 and people would pay $110 for a mature Christmas tree right now, but would only pay $100 for an airtight claim entitling them to delivery of a mature Christmas tree in a year. Furthermore, everyone expects (correctly) that this structure of market prices will be the same, a year from now. In equilibrium, this means that a capitalist could spend $100 today buying a Christmas-tree-that-needs-another-year-to-grow and then hold it for a year. (I’m neglecting any other expenses, including the opportunity cost of the land on which the tree grows.) After a year passes, he sells the mature tree for $110. In general this type of discounting will be applied to factors of production (including labor), and that’s how capitalists earn interest even when they don’t formally lend out a sum of money at a contractual interest rate. Indeed, this is what Bohm-Bawerk referred to as “originary interest” which he (and subsequent Austrians) thought of as more general than the specific offshoot of contractual loans. If you want to see more on this, read up on Bohm-Bawwerk’s masterful demolition of the socialist exploitation theory of interest.

(3) Ah but let me come back full circle: Austrians tend to argue that without money prices various things are metaphorical at best. For example we can vaguely talk about economic calculation in a barter world, but you really need explicit money prices for true accounting to take place. So that’s why I argue in my dissertation for a monetary (as opposed to a “real”) approach to interest theory, where ultimately the market rate of interest is “set” in the explicit, contractual loan market and then the implicit discounts (which also include risk) are adjusted in other intertemporal markets.

“Poor Little Fool”

At my parents’ retirement community I finally found a crowd who liked my kind of music:

Two Kwik Krugman Kontradictions

Nothing earth-shattering, but if criticizing Krugman were an academic discipline, this post would be part of what Kuhn would describe as “normal science.”

==> Scott Sumner explains Krugman’s unfair blanket condemnation of “inflationistas” by reminding us that Krugman (famously) doesn’t read stuff by economists from the other side, but I point out to Scott that Krugman can’t actually rely on that excuse in this case.

==> In this post on US health care Krugman makes two specific claims:

(1) The “pre-ACA system drastically restricted many people’s freedom, because given the extreme dysfunctionality of the individual insurance market, they didn’t dare leave jobs (or in some cases marriages) that came with health insurance. Now that affordable insurance is available even if you don’t have a good job at a big company, many Americans will feel liberated — and this hugely outweighs the minor infringement on freedom caused by the requirement that people buy insurance.”

and

(2) “But no discussion of this latest argument should fail to mention the original insurance-is-slavery campaign — Operation Coffeecup, in which the AMA recruited doctors’ wives to gather their friends and listen to a recording of Ronald Reagan declaring that Medicare would destroy American liberty.”

Does anyone see why that’s at least a Kontradiction, if not an outright contradiction? (Here’s a hint: Medicare went into effect before the Affordable Care Act.)

A Note on the “Real” Rate of Interest

In my Mises Canada post walking through problems with the typical neoclassical approach to capital & interest, I came up with a simple thought experiment in which there are capital goods (nets) that have a positive marginal product–the workers can catch more birds with nets than without. This explains why the nets can earn a positive rent, and why workers would pay a positive spot price for the nets if they wanted to buy them outright.

However, I deliberately designed the example so that the consumption good (birds) trades at par across time periods. This is because the quantity of birds that the workers catch declines each period, perfectly offsetting the natural tendency for positive time preference.

The point of the example was to show that in this contrived setup, where capital goods had positive marginal product but the real interest rate was 0%, the capitalists would earn no net financial return from investing in nets. For example, someone buying a net at the start of period 9 would pay 20 birds for it. During the period, he could rent the net out and earn an income of 10 birds (which is the net’s marginal product for one time period). But the capitalist wouldn’t have earned a net (no pun intended) return on this operation, because the market value of the net would have fallen by exactly 10 birds during the period as well. So his original investment of 20 birds in buying the net, would land him at the end of the period in possession of 10 birds and a net worth 10 birds, i.e. for total wealth of 20 birds which is what he started out with.

I didn’t get into money prices because I wanted to keep things simple, and mainstream neoclassical economists think in terms of simple models like this. (My model is actually more complex than theirs; they usually think in terms of a one-good economy, whereas mine had two–birds and nets.) But I captured the essence of Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of the “naive productivity theory of interest.”

Now in reality, interest payments accrue in the form of money. (Indeed, my dissertation chides even Mises and Rothbard for adhering to a “real” as opposed to a monetary theory of interest.) Let’s think through how we normally correct for price inflation (or changes in “the price level”) when contrasting the nominal versus real rate of interest.

Suppose the nominal interest rate is 10%. So you lend someone $100 today, and get paid back $110 next year. Ah, but in the meantime, “prices” have risen by 3%. So, we say that the “real” or “inflation-adjusted” interest rate is actually only about 7%. More specifically, most economists would look at a basket of consumer goods to gauge the “price level” and say that it has risen 3%.

So if you step back and consider, what we’re ultimately doing is figuring out how many more units of consumption goods people get, if they are willing to postpone consumption for a year. For example, if we start with something that had a price of $1 originally, then the consumer gives up 100 units of consumption by lending out the money. Then next year the lender gets paid back $110. You might think he can buy 110 units of the consumption good, but nope, he can’t get that many, because instead of $1 each now they are $1.03 each. So if he spends the whole $110 on them, he can buy 106.8 of them. (Notice it doesn’t equal exactly 107.0 units; that’s the vagaries of dealing with percentage growth like this. It’s why I said “about 7%” above.) This simple numerical example shows that the person was able to “sell” 100 units of present consumption and “buy” 106.8 units of future consumption. Thus what it means to say “the real rate of interest is about 7%” is to say that units of real consumption trade at 100 units today for (about) 107 units one period later.

Now notice in the discussion above, I didn’t have to specify what was driving the increase in the “price level” and the nominal rate of interest. I didn’t have to explain what the utility function or preference rankings were. If you took my report at face value, namely that the nominal interest rate was 10% and that the price of consumer goods rose 3%, then that was all you needed to conclude that the real interest rate was (about) 7%.

That’s what’s going on with my bird and net example. I cut right to the chase and deliberately designed it so that 1 bird in period 1 trades exactly for 1 bird in period 2, etc. Thus the real rate of interest is zero.

If you want me to give you a story about money prices, I can certainly do that, but it doesn’t affect the essence of the thought experiment. For example, you can suppose that the birds have a price of $1 in period 1, and that the nominal interest rate is 10%. But then the price of birds rises to $1.10 in period 2. So a capitalist who starts out in period 1 with $100 can lend it out to receive $110 next period. That means he sacrifices 100 birds he could have eaten in period 1, in order to have the ability to eat…100 birds in period 2. The real rate of interest is 0%.

Potpourri

==> Richard Ebeling talks about the great Austrian inflation.

==> The Tennessee chapter of NORML put out this publication on quick facts about marijuana legalization. Let me know if you guys spot anything that should be tweaked, because I know these people.

==> A blog post from Mises.org about “the time Murray Rothbard schooled James Buchanan.” The title isn’t misleading; Rothbard wrote to Buchanan, who agreed that Rothbard’s critique was technically correct.

==> Scott Sumner tries to big-tent me. I agree he and I both belong to the category, “Blogging economists who have a very high opinion of themselves.”

==> I obviously disavow the concluding remarks, but in this post Matt Yglesias does a decent job summarizing the Cambridge Capital Controversy. I bring this up mostly to say that I’m not being partisan when I claim that Thomas Piketty literally doesn’t know the first thing about it.

==> I was never jealous that Tom Woods’ Politically Incorrect Guide book outsold mine, but boy that’s neat he gets to interview Pat Buchanan. (I used to watch Crossfire back when my friends were going on dates in high school.) There’s an amazing part where Buchanan says something like (and I’m paraphrasing), “Churchill deliberately misled his own people about Stalin. I mean, there are certain things you have to do diplomatically. For example, I had to write toasts for Richard Nixon to give to communist leaders that would turn your stomach…”

The Kids Can’t Get Enough Murphy

Dennis Foster emails me (and gave permission to quote):

Message: Hi Bob,

I’ve had the pleasure of taking many of your on-line classes with the Mises Institute over the years (I can’t believe it’s actually been years!). In my Public Choice Theory class, we finish the semester with your Chaos Theory book, to illustrate the extremes to which we can push the idea of minimizing the role of the state. On the final exam, which we just finished, I have an essay question on your notion of a private defense system and I thought I’d share with you the opening paragraph one of my students wrote in addressing this topic:“When I first read about Murphy’s idea of a private defense system, I was a little skeptical because I did not understand it. But now that I do understand it, I could advocate (for) it. The idea of having a privatized defense system is really interesting. The fact that it would be through firms and not the government is interesting.”

Dennis Foster

Here is the PDF of my pamphlet Chaos Theory. But, before you read that, I recommend these two articles I did for Mises.org which will provide a better foundation for the mechanisms I discuss in the pamphlet.

Bill Cosby Dispelled the Evil Spirits Keeping Him Down

This isn’t exactly religious, but it’s spiritual in a way. I found this very moving. It’s Cosby’s acceptance speech for the recent American Comedy Awards.

YouTube’s Embed info isn’t loading for some reason, so I’ll send you directly to the link.

Piketty Can’t Even Get His Basic Tax History Right

The more I read of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the worse it gets. Try this excerpt:

[T]he Great Depression of the 1930s struck the United States with extreme force, and many people blamed the economic and financial elites for having enriched themselves while leading the country to ruin. (Bear in mind that the share of top incomes in US national income peaked in the late 1920s, largely due to enormous capital gains on stocks.) Roosevelt came to power in 1933, when the crisis was already three years old and one-quarter of the country was unemployed. He immediately decided on a sharp increase in the top income tax rate, which had been decreased to 25 percent in the late 1920s and again under Hoover’s disastrous presidency. The top rate rose to 63 percent in 1933 and then to 79 percent in 1937, surpassing the previous record of 1919. [Piketty pp. 506-507]

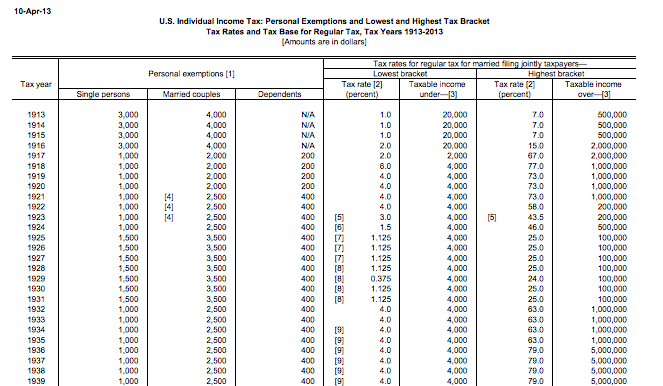

Look, I don’t mean to be a stickler, but the above tax “history” is totally wrong. Here is the actual history of the top federal income tax rate, from the Tax Policy Center:

The column you want to look at is second from the right. A few things:

(1) The top rate was lowered to 25 percent in 1925, not exactly “the late 1920s” and certainly not by Herbert Hoover. (I think the brief 24 percent rate in 1929 was a one-off adjustment in the surtax, but I am not certain and I’m not going to go look it up right now.)

(2) The top rate was jacked up to 63 percent in 1932, not 1933, and it was done by Herbert Hoover, not by FDR. (Note that the 63 percent rate applied to the 1932 tax year, so we can’t rescue Piketty by saying he was referring to the first year of impact rather than the passage.)

(3) The top rate was raised to 79 percent in 1936, not 1937. (If you want to cross-reference another source, this page also agrees that the 79 percent rate kicked in in 1936.)

Now if there had just been one instance of Piketty being off by a single year, I would excuse it by saying maybe he got mixed up in interpreting how US tax laws work. But to say (or did he merely imply?) that Hoover was the one to lower tax rates to 25% is just crazy; Hoover wasn’t inaugurated until March 1929, and the top rate was lowered to 25% back in 1925.

Furthermore, notice that this isn’t an “arbitrary” screwup on Piketty’s part: On the contrary, it serves his narrative. It would be really great for Piketty’s story if the right-wing business-friendly Herbert Hoover slashed tax rates to boost the income of the 1%, thereby bringing in a stock bubble/crash and the Great Depression. Then FDR comes in to save the day by jacking up tax rates. Except, like I said, that’s not what actually happened.

So let’s see: The #1 Amazon bestseller is a work involving a theoretical mechanism that explains how interest rates will interact with GDP growth in order to yield an ever-rising share of capital income, and this is embedded in what is (we are told) a masterful historical analysis of tax policy and income distribution. So far we’ve seen:

(a) Piketty’s theoretical structure suffers from basic confusion, which was so bad that Nick Rowe declared in the comments here: “If an economist writes a whole book about capital and the functional distribution of income, you would think he would at least understand the very basics of the theory of capital and interest. He does not.

Bob is absolutely [right] about this. How come anyone takes this stuff seriously?”

(b) Piketty truly doesn’t know the first thing about the Cambridge Capital Controversy.

and

(c) Piketty botches basic historical tax facts, in a way that helps his narrative.

But hey, it’s all good. He gives us a scientific justification for taking property away from rich people. Why let the above quibbles get in the way of worldwide confiscation?

Recent Comments