Shocking Quotes from Piketty

You know how some of you have been saying, “What the heck Murphy, why do you keep talking about this Piketty book? So what if it was #1 on Amazon, and all the progressives are giddy about it? He just wants to raise tax rates right?”

Uh, no. Check out my latest Mises Canada post. You need to realize what is in this book. It’s not simply that he has a bad theory of interest or ignores supply-side effects on estate tax bases (as Martin Feldstein points out, correctly). Here I’ll give you just three examples, but click the link for more:

“Taxation is not a technical matter. It is preeminently a political and philosophical issue, perhaps the most important of all political issues. Without taxes, society has no common destiny, and collective action is impossible.” (p. 493)

“When a government taxes a certain level of income or inheritance at a rate of 70 or 80 percent, the primary goal is obviously not to raise additional revenue (because these very high brackets never yield much). It is rather to put an end to such incomes and large estates, which lawmakers have for one reason or another come to regard as socially unacceptable and economically unproductive…” (p. 505)

“From the standpoint of the general interest, it is normally preferable to tax the wealthy rather than borrow from them.” (p. 540)

2014 Night of Clarity — Featuring David Stockman

This is the annual event that Carlos Lara and I put on, in downtown Nashville. Here is the official event page.

Other confirmed speakers: Tom Woods, IBC founder Nelson Nash, and FEE’s Larry Reed.

Is God Funny?

Since I’m such a wiseguy, I would like to think this activity is encouraged (if it’s in good fun of course), but it’s not obvious that it is. Here are some of my quick reflections on the question of whether God is funny:

==> If God is funny, His humor is definitely of the deadpan variety. (On Facebook I once imagined meeting God after death and asking, with all due humility and respect, if He could explain His plan which had made no sense on Earth. God replies, “Oh that? I was just trolling you guys.”)

==> Jesus was obviously very clever–look at His battle of wits with his interlocuters–but He didn’t really walk around cracking jokes, at least not in His recorded sermons. Now maybe that’s because He would warm the crowd up with observational humor, then hit them with the really deep stuff, and the people writing the gospels obviously focused on how to get into heaven, rather than remarks on the difficulty of making a level table. But I also recall Oscar Wilde’s line: “If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you.” Since Jesus’ mission was to provoke the religious leaders into plotting His death, He couldn’t really be a standup comedian.

==> There are different roles for the Jester versus the King. Just because the King doesn’t crack jokes doesn’t mean he has no sense of humor; if he keeps around the Jester, we think he does.

==> And on that note, let me make my final observation on the issue of whether God has a sense of humor: Look at the group He made His chosen people.

Even More Inventory Scenarios

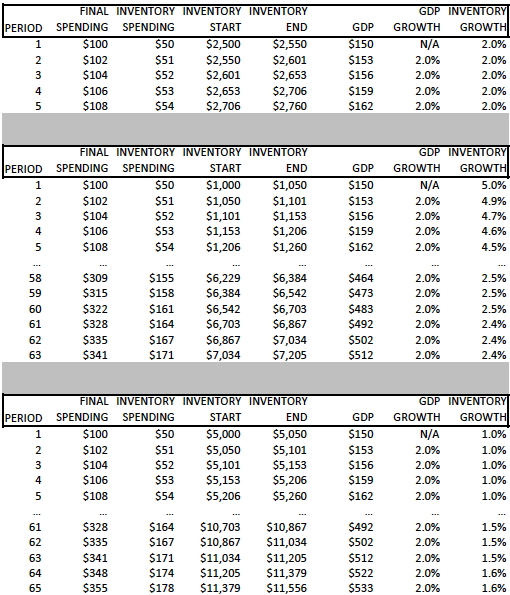

Tel and I have been going back and forth in the comments… He pointed out that if inventory grows at 2% forever (along with final sales), then GDP growth is a constant 2%. But be careful, what’s going on is that a constant 2% growth in inventories implies a constant 2% growth in the *change* in inventories, which is the relevant issue.

Below the first example shows what Tel is talking about, but the next two show what I am warning about. Note that inventory growth converges to 2% from both ends, even though GDP growth is a constant 2%.

More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Inventory Adjustments in GDP Accounting

Whether it’s government debt-burdened grandchildren, marginally productive capital, or inventory adjustments in GDP accounting, I don’t rest until I have resolved the issue to my own satisfaction–even if the rest of the world has moved on by that point.

Anyway, drawing on a neat idea from “Transformer” in the comments here, I discuss this issue more at Mises Canada. An excerpt:

So what should our hypothetical analyst think, now that he has decomposed the total GDP growth figures into their final purchase and inventory components? I submit that we could tell any story we want. What matters is not the ex post figures, but what the business owners planned ex ante.

Before I explain what I mean, first ask yourself: Why do businesses carry inventory in the first place? One major reason is that they want to have a buffer in between final demand and production. The owners don’t want to lose potential sales while the factories are churning out additional units. So that desire leads businesses to accumulate inventories. On the other hand, they don’t want to carry too large of an inventory, because that ties up capital which could be earning interest. The actual desired level of inventories are an interplay of these (and possibly other) factors.

What these observations mean is that if a business owner expects sales to pick up in the future, he might intentionally bulk up his inventory. For example, the inventories carried by Halloween costume shops are certainly much higher on October 15 than on November 15. This is why we can’t derive much information from looking at changes in inventory per se.

Potpourri

==> Dan Sanchez talks about inflation and milkshakes.

==> In this older interview with Russ Roberts, Pete Boettke lays out a neat analogy for Austrian vs. neoclassical capital theory: Legos vs. Play-Doh.

==> An interesting analysis of government vs. market failure in leading textbooks. Krugman is the Team Leader.

==> Reconciling Hayek and Keynes.

==> David Friedman recommends a method for boarding airplanes, but isn’t that how they do it with “zones”?

==> Alchian had a pretty sweet idea to find out classified information. Go market!

==> Science doesn’t support the National Climate Assessment’s scare tactics. I explain at IER.

Larry Summers Unwittingly Blows Up Piketty’s Whole Book

…but he still thinks Piketty should get a Nobel Prize. The gory details are at Mises Canada. An excerpt:

Piketty wants to scare his readers into believing that the percentage of income each period going to the capitalists will increase over time, meaning that “the workers” will earn a lower portion of total output in, say, 2100 than they do right now. So he needs to argue that the parameters on his assumed production function are such that an increase in the capital stock of x% will lower the return to capital “r” by less than x%. In the jargon of economists, Piketty needs to argue that empirically, the “elasticity of substitution” is greater than 1.

Piketty does indeed try to show this, by pointing to some of the high-end estimates in the literature putting the elasticity at 1.25. Yet as Rognlie the MIT grad student points out, this is confusing gross with net returns. If you are a capitalist who owns a bunch of machines, your *net* income each year is equal to

==> your gross rental income from your machines

==> minus the drop in the market value of your machines, either due to a change in prices or physical depreciation.

So as Rognlie and now Larry Summers confirm, there are no empirical estimates of an elasticity in substitution being so much above 1 that the share of *net* income (after accounting for physical depreciation) going to capitalists would be expected to indefinitely increase over the coming decades, as the capital stock accumulates.

The Absurdity of Conventional GDP Accounting

In two weeks the BEA will announce an update on its estimate of 1q 2014 GDP growth, but I want to point out a problem with the “advance estimate” (of a dismal 0.1%) that they issued at the end of April. Here is how Forbes reported it at the time:

The U.S. economy grew in the first quarter — but very, very, very slowly. Most economy watchers blame frigid winter weather for dampening forward progress but not everyone is convinced weather tells the whole story.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis’ advance estimate of first quarter 2014 real gross domestic product shows output produced in the U.S. grew at a glacial 0.1% rate. This is growth relative to fourth quarter 2013, when real GDP increased 2.6%. Economists were anticipating growth around 1.1%.

…

Most of the weakness came from trade and inventories which subtracted 80 basis points and 60 basis points from overall GDP respectively. According to BEA, the slowing growth also reflected a downturn in nonresidential fixed investment growth, as well as lower state and local government spending. [Bold added.]

The fundamental confusion in conventional GDP accounting is that it relies on spending as a measure of economic output. Yes, there is a certain logic in this; if businesses sell $15 trillion worth of stuff, then their customers must be buying $15 trillion worth of stuff. Yet it is still a very dangerous game, because it leads people to confuse accounting tautologies with economic causality: they think that the way to boost economic growth is to hike government spending, for example.

Yet things are even worse. Because policymakers and the pundits routinely refer, not to GDP itself, but to GDP growth, then “contributions to” or “subtractions from” GDP growth are actually second derivatives of the various variables involved.

For example, consider the recent GDP report. The Forbes article tells us that “inventories” subtracted “60 basis points from overall GDP.” What the heck does that even mean? How can goods sitting on warehouse shelves affect the ability of workers to take resources and produce output?

Of course, the ultimate explanation here is that the first pass at calculating GDP looks at the final spending by customers. Then, we look to see how much inventories changed during the period. For example, if customers spent $15 trillion on final goods, but during that period inventories fell by $1 trillion, then actual new production that period must only have been $14 trillion.

OK, so since inventory was apparently responsible for shaving 60 basis points off of GDP in the 1st quarter, I guess inventories across the US fell from 4q 2013 to 1q 2014, right?

Nope, that’s not right. The BEA report tells us (and note that that hyperlink will only be valid until the next BEA news release): “The change in real private inventories subtracted 0.57 percentage point from the first-quarter [2014] change in real GDP after subtracting 0.02 percentage point from the fourth-quarter [2013] change. Private businesses increased inventories $87.4 billion in the first quarter [of 2014], following increases of $111.7 billion in the fourth quarter [of 2013] and $115.7 billion in the third [quarter of 2013].”

Now we see why I was talking about second derivatives. Private inventories have been increasing in each of the last three quarters. But the increase (in dollar terms, and a fortiori in percentage terms) has itself been shrinking each quarter. That’s why inventories “subtracted” 2 basis points from GDP growth in 4q 2013, and “subtracted” 57 basis points (which the Forbes article rounded to 60) in 1q 2014.

If you want to see a more careful exposition of these ideas, and a simple numerical example to pinpoint the craziness, read my article at Mises.org cleverly titled, “Inventories Don’t Kill Growth–People Kill Growth.”

Recent Comments