Defending the Fine-Tuning Argument for God

Last week I alluded to the fine-tuning argument for the existence of God, without mentioning my responses to standard objections. So I’ll do that today. Before diving in, I want to remind people that I used to be a “devout atheist” (my terminology), and if I do say so myself, I could talk a good game. That doesn’t mean I’m right, now that I’ve flipped sides, but it does mean that I honestly understand why the atheists/agnostics think they have knock-down arguments; I used to think so too. But after further review, the play is overruled. First down, Jesus.

First let’s deal with Aristos, who–as a good Catholic–wasn’t doubting my conclusion, but wanted to make sure we were using a valid argument. He asked:

Wasn’t it Feynman who posed something like, “What are the chances that a vehicle with that exact license plate passed before me at that exact time?”

I’m not rejecting God. I just wonder at the argument. Many things that are quantifiably unlikely (if that’s even a reasonable expression) are possible and occur everyday.

Yes, that was physicist Richard Feynman, a guy very high on my list of dead people I’d like to meet. I don’t remember the context of his observation, i.e. whether he was commenting on objections to evolutionary biology, or just about innumeracy in general.

But by all means, let’s delve into that analogy. Suppose a license plate has seven slots, any of which can be a number or a letter. So there are 36^7 ( = ~78 billion) possible license plates.

You and I are sitting in traffic. I remark, “Heh, I bet that guy in front of us didn’t vote for McCain.” You wonder how I can possibly know that. I say, “Look at his license plate–it says ‘LUVBAMA’. The chance of that happening randomly is 1 in 78 billion. It can’t be a coincidence.”

Now it would be silly for you to say, “Bob, no matter what sequence of digits and letters we observed, the probability of that particular string would be 1 in 78 billion. So we have no reason to deduce that that string gives us information.”

It’s the fact that the string of symbols appears meaningful that makes its improbability an indication of a mind at work. To be sure, there are lots of phrases that would have made me equally surprised, such as “HOPECHG” or “DEMOCRT”. So it’s not quite right to say the chance is 1 in 78 billion; maybe it’s more like 10,000 in 78 billion. Then when you throw in the fact that you will see (say) 5,000 different license plates this year, you can say, “The probability of me seeing a message that (apparently) meaningful, at any time during this year, is 1 in 1560.” So now it’s not so ridiculous to attribute it to pure chance, but it’s still pretty tenuous.

(Note I’m being a little vague on how we incorporate our prior knowledge about how typical it is for people to get vanity plates, etc. For example, if you were pretty sure that a state didn’t allow vanity plates, then you would be more willing to believe an apparently meaningful license plate was random.)

Anyway, I hope I’ve given enough to make my position clear: Yes, no matter what happens, it must have been possible–that’s what happened. But look at how we use our common sense in everyday life: If we’re walking along the beach, and see a bunch of rocks and shells arranged in order to spell “SHIPWRECKED PLEASE SEND HELP”, we are going to be dead certain that a human being did that. Somebody who said, “No, it could have been the waves randomly depositing the shells and rocks in that position, and we know it must be possible because it just happened” would be ridiculous.

This is probably a good time to throw out a thought experiment I came up with to challenge (what I consider to be) the untenable position of a lot of the “scientific” critics of Intelligent Design theory. (BTW, of course I acknowledge that a lot of the “Darwin’s from the devil!” crowd haven’t read much of evolutionary biology before spouting off.)

Anyway, suppose a biologist is doing some standard data entry on the human genome project, and is just screwing around playing with the DNA sequences that apparently don’t serve any purpose. I.e. everybody thinks this particular string of nucleotides is just taking up space. In fact it’s a compelling argument against those Bible-thumpers: Why would an intelligent God give us vestigial organs, and noisy stretches of DNA to boot?

So anyway, the analyst is playing around and on a lark he runs the sequence of A, C, G, T through a decoding algorithm that he had been working on, as part of his spy hobby. He almost has a heart attack when the following output shoots out:

1In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

2And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

3And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

4And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

The analyst starts checking other parts of the sequence, and he realizes that the entire King James Bible is embedded in the human genome, in an area that scientists previously thought served no evolutionary purpose.

The analyst stays up through the night, making sure he is using the same “neutral” algorithm that he had been working on when he was pretending he was cracking the Enigma code; he wants to be sure someone isn’t playing a trick on him.

Finally, at about 6 am he makes the most important blog post in world history–he puts up his algorithm, and gives other biologists instructions as to where in the human genome to start applying it.

Within days word has spread from beyond the scientific community into the pulpits. Preachers who don’t know the first thing about the Intertubes are proclaiming absolute victory in the debate over the existence of God.

Yet the atheists aren’t flustered one bit. They explain–quite correctly–that the conditions of the earth must have been such that those nucleotides conferred an evolutionary advantage. In fact, it was a repudiation of science itself to start looking for mythical men in the sky to explain findings in the laboratory. In any event, there is a lot of room for “messages” to be embedded in DNA; it is an elementary fallacy to be shocked at the “unlikelihood” of the particular codes.

(In case the point of my story isn’t clear: Yes, of course we can “explain” our bodies, including our brains, by reference to the conditions of the material earth and what would have conferred an evolutionary advantage. But if the result still contains an incredible amount of information, then it just pushes back the problem one step: Why should it be, that we evolved in a world that favored the development of creatures like us?

This, incidentally, is Michael Behe‘s position. As I understand it, Behe isn’t bothered by the theory of common descent–which says that all living things on earth today, come from a single cell. What he is saying is that if this is true, then that single cell–in conjunction with the environment in which it started reproducing–had a heck of a lot of information packed into it, which can’t be due to blind chance.)

OK and now very briefly, let me deal with the anthrophic principle: This view says, “Of course we live in a universe where the charge on an electron is just right, and Jupiter protects the earth from killer comets. If we didn’t, then we wouldn’t be alive to wonder at our good fortune.”

The only way this works, is if we also buy into the many-universes view. For example, if every possible universe exists, then of course there will be intelligent beings in some of them.

I have said this before, and I’ll repeat it here: Of course I can’t prove that there aren’t an infinity of alternate universes; by definition, we can’t observe them. But notice that this view–which is critical to the entire edifice of the atheist’s worldview–is the epitome of (a) non-falsifiable and (b) a violation of Occam’s Razor.

In other words, it is literally impossible to come up with a theory that is more fundamentally non-falsifiable than that of the multiverse; you can’t possibly observe something that is not in your universe.

Second, as far as a theory relying on “other stuff” to work, you couldn’t possibly come up with something that requires more than the theory saying we must assume an infinite number of other potential universes in order to work.

So I admit, that doesn’t rule out the theory. But it’s a bit odd coming from people who often champion the criteria of falsifiability and Occam’s Razor as the hallmarks of science (as opposed to faith).

First Sliced Bread, Now This

I know I know, you go to a cocktail party, and you tell people about the Murphy-Krugman debate, but you can’t do justice to all the funny videos and the serious article exchanges. Well, now you just take the person’s hand and write “KrugmanDebate.com” on it. You’re golden.

Different Analytical Frameworks

I’m doing this as a separate post because I want to keep the arguments distinct… Let’s go back to this example from Scott Sumner:

NGDP is $10, and each of ten workers [gets] a dollar in wages. Now they negotiate a 10% wage increase, in anticipation of 10% more NGDP. So wages rise to $1.10. Now there is only enough NGDP to emply nine workers, because NGDP unexpectedly stayed flat at $10. And that is true no matter how high productivity rises.

What is so intriguing to me about Scott’s worldview is that he looks at things that, in my mind, are effects, and attributes causal power to them. And yet, it’s hard for me to attack his position, since our differences are almost metaphysical.

So for one thing–and I don’t mean this as a cheap shot–when is the last time you negotiated a wage increase “in anticipation of 10% more NGDP”? It’s not even true that employers do that. They might concede to wage hikes because they anticipate higher P, and for sure if they anticipate higher PxQ of their output, but I don’t think too many people are walking around, thinking about what NGDP will be next year. I say this, because I have to be careful to define NGDP whenever I write about Scott in polite company.

Let me reiterate my reasons for bringing up productivity in the original gauntlet I threw down to the quasi-monetarists. Remember, they are saying that the main problem with the economy is that total spending fell in late 2008. They concede that with perfectly flexible wages and prices, that wouldn’t be a problem; it would just change nominal values, but nothing “real.” But shucks, in the real world, some prices and especially wages don’t fall easily, and so a sudden drop in total spending (NGDP) will lead to high unemployment.

OK, so then I pointed out that NGDP has recovered, and in fact is currently the highest in US history. So why hasn’t full employment resumed?

Now if I were going to explain this, using sticky prices and wages, I would give a simple numerical example like this: Before the recession, each of ten workers got $1/hr in wages, each produced 1 widget per hour, and the price of widgets was $1.

But now, productivity has risen. Each worker can produce 1.1 widgets per hour. Yet because wages and prices are stuck at $1, the employer can’t afford to keep all ten workers employed. Since he is stuck paying them $10 total per hour, consumers only have $10 to spend on each batch of widgets. That was fine before, when widgets cost $1 each and there were ten produced per hour.

But now, if the employer holds all 10 employees, every hour an extra widget piles up, because the workers produce 11 per hour but can still only collectively afford to buy 10 per hour.

Now if things were flexible, it would be simple: The employer could either raise wages to $1.10 per hour, or he could cut the price of widgets to about 91 cents each. Either way, the real wage would increase, and workers would earn enough income to be able to buy enough product to keep them all employed.

Now note, I hate thinking in these terms, but if I were forced at gunpoint to do it, this is how I would go about it. I don’t even know what it means to talk about, “What if total spending is $10, but everyone expected it to be $11?” We know what the determinants of “total spending” are, so I would rather discuss theories of what moves those things.

Let me make sure you get what I’m saying: In my example above, I think you could tell an NGDP story to “explain” why there was unemployment, and then how it got solved. When W and P were stuck at $1 each–while worker productivity went up 10%–NGDP didn’t grow; it stayed flat at $10.

Now consider the solution scenario where W goes up to $1.10 per hour. In this case, the workers are earning $11 total per hour, and they produce 11 widgets total per hour, so they spend the $11 buying it. So NGDP (per hour) rose from $10 to $11. “Aha!” Sumner exclaims. “Once we boosted NGDP by 10%, the unemployment problem was solved!”

Now consider the other solution scenario, where P drops to 91 cents per hour. In this case, the workers are still getting paid $1 per hour. They can each afford to buy 1.1 widgets per hour, and so the 10 workers collectively buy 11 widgets for $10 total. So NGDP stays constant at $10. Sumner says, “Aha! Just as my theory predicts. Constant NGDP is consistent with rising real GDP and full employment, so long as prices can adjust downward.”

I haven’t quite put my finger on it… I just think there is something fishy in reasoning from “NGDP.”

Let me take one more stab at this and I’ll drop it for a while… If I’m looking at the world in terms of NGDP, where “total spending” is a concept that has explanatory power, I might reason like this: “During a recession, consumers are only spending, say, $13 trillion on output, but at the current level of output prices, that only corresponds to 97% of last year’s output. So that means employers have no choice but to lay off, say, 10% of the workers, so that the remaining (and most productive) 90% of the workers can produce 97% of last year’s output. So the unemployment rate goes up to 10%, and real output falls by 3%; we’re in a bad recession. The way to fix this, is to reduce the unit price of output. That way, with $13 trillion in spending, consumers can now afford to buy the same amount of stuff as last year. So employers can go ahead and hire back those laid-off workers, since there is now the demand to soak up the excess capacity.”

I think that has a certain plausibility, if you reason in terms of NGDP causing recessions. But if you think of it in terms of microeconomics, it makes no sense: It says the way to fix a glut in the labor market, is to make real wages go up. When macro reasoning seems to contradict micro reasoning, I feel on much safer ground by going with the micro.

Now I think there must be some resolution to this apparent paradox, in that things happen with “the velocity of money” (another term that doesn’t make sense at the individual level) and so on, so that NGDP changes as it needs to, to correspond with what we know from micro analysis.

Either that, or I’m going down a blind alley. It’s been a long week, you guys can hash it out in the comments.

Sumner Provides an Answer…Or Does He?

Apparently there are a fixed number of comments to be posted on this blog per week, and so if I don’t keep the posts flowing, you guys pile up 58 comments in a single one.

Because of this, many readers may not have seen Scott Sumner’s reply to my queries. (If you need to refresh your memory, here ya go.)

This was Scott’s response (I fixed a typo), and then I reproduce my reply below it:

1. NGDP growth slowed steadily. It was lower in the first half of 2008, then in 2006 and 2007. That slowdown in demand helped slow RGDP growth. Because of the slow growth in overall demand, the fall in housing construction (and autos due to high oil prices) was not fully offset by gains elsewhere. Hence RGDP was flat in the first half of 2008. Housing and autos declined, other output rose, but only about the same amount. Flat RGDP is a very mild recession.

2. I don’t understand why you think the rise in productivity solves the sticky-wage problem. The rise in productivity does help boost output, but it doesn’t put people back to work. If national income is barely higher than two years ago, and people who are employed make often make more than two years ago, and profits have risen due to productivity, then as a matter of sheer arithmatic won’t there be fewer people employed?

3. Follow up to previous example. NGDP is $10, and each of ten workers ge s a dollar in wages. Now they negotiate a 10% wage increase, in anticipation of 10% more NGDP. So wages rise to $1.10. Now there is only enough NGDP to emply nine workers, because NGDP unexpectedly stayed flat at $10. And that is true no matter how high productivity rises. Obviously the real world was more complex, but that’s what I see as the flaw in your logic.

And my reply:

Scott,

Thanks for the replies. Quick responses:

On (1): So housing construction has nothing to do with it, right? If NGDP had grown at the same rate through early 2008, then RGDP wouldn’t have gone flat? So rather than having two explanations–a real one for the mild recession and a nominal one for the sharp recession–you have one explanation, I think. Specifically, NGDP slowed in early 2008, so there was a mild recession, and then when NGDP crashed, there was a bad recession. Right?

On (2) – (3): You are misunderstanding me. I said right in the beginning that rising productivity would hurt things, if one thought people needed to spend enough to “buy all the products” to keep everybody employed. But my point was, in that case, you should be rooting for CPI to fall, and yet you don’t.

Last point–not to Scott, but to people who thought I was an idiot for saying Scott would think rising productivity would hurt things–I told you so.

I Demand Answers From the Aggregate Demanders

Just to clarify, when I say I’m an aggregate demand skeptic, I don’t mean to deny that aggregate demand exists, at least in principle (though we might not measure it well). I also don’t mean to deny that it does indeed sometimes fall sharply. Further, I concede that these falls are caused by human activity, and not sunspots. However, what I am skeptical about is that these anthropogenic falls in aggregate demand are damaging to human welfare, and what I outright deny is that Ben Bernanke can make things better if we gave him a printing press and just let the guy do his job, for crying out loud.

I am going to write up a careful response to the quasi-monetarists (people like David Beckworth and Scott Sumner), but first I want to make sure I understand their worldview. So some questions:

(1) For Scott, you say that the recession that officially began in December 2007 was due in part to a fall in housing construction. But can that be, since you have demonstrated that housing construction started collapsing back in 2006? Why didn’t the maintenance of NGDP growth all through that period ensure that the decline in housing construction was offset by increases elsewhere in the economy? (Note: I know you distinguish between a mild “real” recession starting in late 2007, and the big boy “nominal” recession starting in June [?] 2008 when NGDP growth collapsed. So put the later recession aside. Just looking at the first one, how does your timeline work? How can a collapse in housing construction that started in early 2006, explain a recession that didn’t start until December 2007? And of course, whatever reason you give, then explain why I can’t use the same reason to get out of the cage you thought you had put over Arnold Kling and me, regarding unemployment. E.g. is a one-year lag OK, but a two-year lag is pushing it?)

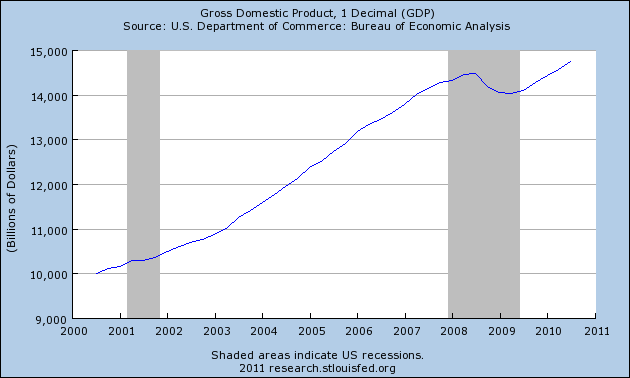

(2) As I understand Beckworth and Sumner, their position is that nominal income collapsed in 2008, and so there wasn’t enough total spending to keep everyone fully employed. It’s true, if all prices and wages were perfectly flexible, there’d be no problem. But since wages in particular are sticky downward, the drop in total spending is accommodated by a fall in real output. Yet in that case, the following chart is interesting:

Nominal GDP–i.e. total spending–is now the highest it has been in US history. So why is unemployment still so high? I can imagine one possible answer: Because productivity has grown in the meantime, so that the mid-2008 level of total spending is now only sufficient to employ 91% of the workforce. Yet if that is the answer, then doesn’t it solve the “sticky wage” problem? In other words, if the problem as originally conceived was that falling prices combined with sticky wages led to above-equilibrium real wage rates, the shouldn’t an increase in productivity mitigate that problem? Employers just keep nominal wage rates at their “stuck” level, and the ever-improving workers raise the equilibrium wage rate up and up, shrinking the gap.

So to repeat, I think the explanation–at least if Beckworth/Sumner like the “productivity has grown” answer for why record-breaking NGDP hasn’t pulled us out of the recession–is internally inconsistent. If stagnant NGDP is only a problem because of sticky wages, then it doesn’t make sense (at least to me) to say, “Oh shoot, if only productivity hadn’t grown the last 2 years, we’d now be at full employment.”

This is a crucial point, so let me put it differently. Suppose there had never been any problem with AD. Instead, back in mid-2008, all of a sudden there was a huge leap in worker productivity–namely, workers back then suddenly became as productive as they are (in reality) right now. Now with sticky prices and wages, this could lead to a big spike in unemployment: The fully-employed factories are cranking stuff out, and inventories are piling up, because employees still have the same take-home pay, and the owners refuse to cut prices. So the workers don’t have enough total income to buy the higher output, at the original prices. So in this case, wouldn’t the goal would be to reduce the price level? But if so, then why in our environment, does Scott (not sure about David) think the Fed’s policies are starting to work when price inflation ticks up? (I have seen him say that on his blog; I’m not conflating “I think the Fed needs to do more to boost AD” with “I want higher price inflation.”)

(3) For my third question, I want David and/or Scott to give me their take on this graph:

Isn’t it a bit weird, if the alleged problem is one of wages and prices that are rigid downward, that both CPI and average hourly wage rates are at all-time highs? If we have a glut in the labor market, because at least one of those things (wages or prices) is stuck against a binding constraint, then why are they both moving upward? Furthermore, even the gap between the two has grown back to its level of the period during the peak housing bubble years, when there was no unemployment problem.

I think Scott may say, “When we speak of wages being ‘sticky downward,’ that’s sloppy. Actually wage contracts have built-in increases, and there is an expectation among workers that they will get raises. So it’s not that wages are flat and can’t sink to restore equilibrium, it’s worse than that: Wages are ‘stuck’ on an upward trend.”

If that is indeed his answer, then fine, but then I repeat my question from (2): If the problem is that nominal wages are rising too quickly, then wouldn’t the solution be to boost productivity? In that way, the workers could deserve their nominal wage increases. And yet, I thought we had to cite “rising productivity” as the reason for why record-high NGDP hasn’t gotten us out of the rut yet.

NOTE: I am not claiming that I’ve found actual contradictions in the Beckworth/Sumner worldview; I know there are internally consistent formal models with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed. But I’m saying from the verbal discussion of those models, I can’t keep things straight. So please enlighten us, you monetarist Keynesians you.

I Agree With Krugman

…when he writes:

[M]onetarists — old-style Friedman-type monetarists who focus on monetary aggregates, or the new style which says that the Fed can and should target nominal GDP — are, whether they realize it or not, part of the axis of monetary evil as far as the demand-deniers are concerned. They may believe that they can limit the scope of demand-side reasoning, making it a case for technocratic policy at the central bank but no more than that. But from the point of view of those who can’t see how demand can possibly matter, they’re essentially in the same camp as Keynesians. And you know, they are; once you’ve accepted the idea that inadequate demand is the problem, the role of fiscal as opposed to monetary policy is just a technical detail (albeit one of enormous practical importance).

This is exactly why I classified David Beckworth’s National Review article as “monetarist Keynesianism.” Beckworth thought that was a contradiction in terms,* but no it isn’t. Don’t take my word for it, ask the Nobel laureate.

Now of course, Beckworth might still be totally right; tagging him with the K-word isn’t the end of the story. I was mostly making the point in my original critique of him, that it’s going to be hard to appeal to conservatives with arguments that would justify the Obama stimulus package. At some point in the near future I will address the purely technical aspects of Beckworth’s views.

* Actually it might not have been Beckworth who used the phrase “contradiction in terms,” since I can’t find him saying that right now. But I swear that one of those guys (Woolsey, etc.) responded to my critique of Beckworth by saying “monetarist Keynesian” is a contradiction.

Murphy Moving Mainstream?

If I were a male model, Will Ferrell would lean to his right and comment, “He’s so hot right now.”

* The Economist magazine’s blog discusses the tag-team showdown between Kling and me, versus Scott Sumner. But then David Beckworth comes in and hits me in the back of the head with a steel chair.

* Pete Boettke wants me to take the battle to the academic journals.

* Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge says my reply to Krugman is “must read.”

* In fact, I am so relevant these days–part of the conversation, at the table, you get the idea–that Tyler Cowen assumes there is an 87% probability that his readers know all about me.

I am waiting for MSNBC to offer me Olbermann’s slot.

Recent Comments