I Demand Answers From the Aggregate Demanders

Just to clarify, when I say I’m an aggregate demand skeptic, I don’t mean to deny that aggregate demand exists, at least in principle (though we might not measure it well). I also don’t mean to deny that it does indeed sometimes fall sharply. Further, I concede that these falls are caused by human activity, and not sunspots. However, what I am skeptical about is that these anthropogenic falls in aggregate demand are damaging to human welfare, and what I outright deny is that Ben Bernanke can make things better if we gave him a printing press and just let the guy do his job, for crying out loud.

I am going to write up a careful response to the quasi-monetarists (people like David Beckworth and Scott Sumner), but first I want to make sure I understand their worldview. So some questions:

(1) For Scott, you say that the recession that officially began in December 2007 was due in part to a fall in housing construction. But can that be, since you have demonstrated that housing construction started collapsing back in 2006? Why didn’t the maintenance of NGDP growth all through that period ensure that the decline in housing construction was offset by increases elsewhere in the economy? (Note: I know you distinguish between a mild “real” recession starting in late 2007, and the big boy “nominal” recession starting in June [?] 2008 when NGDP growth collapsed. So put the later recession aside. Just looking at the first one, how does your timeline work? How can a collapse in housing construction that started in early 2006, explain a recession that didn’t start until December 2007? And of course, whatever reason you give, then explain why I can’t use the same reason to get out of the cage you thought you had put over Arnold Kling and me, regarding unemployment. E.g. is a one-year lag OK, but a two-year lag is pushing it?)

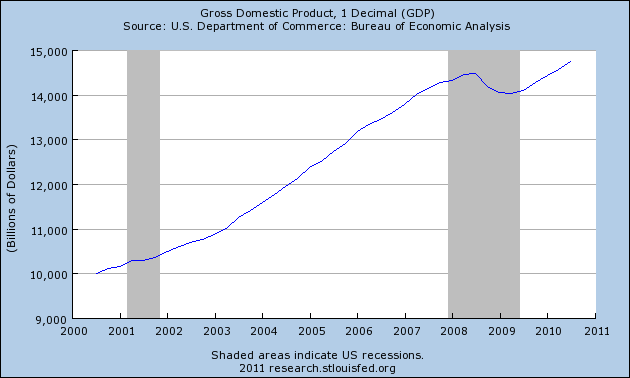

(2) As I understand Beckworth and Sumner, their position is that nominal income collapsed in 2008, and so there wasn’t enough total spending to keep everyone fully employed. It’s true, if all prices and wages were perfectly flexible, there’d be no problem. But since wages in particular are sticky downward, the drop in total spending is accommodated by a fall in real output. Yet in that case, the following chart is interesting:

Nominal GDP–i.e. total spending–is now the highest it has been in US history. So why is unemployment still so high? I can imagine one possible answer: Because productivity has grown in the meantime, so that the mid-2008 level of total spending is now only sufficient to employ 91% of the workforce. Yet if that is the answer, then doesn’t it solve the “sticky wage” problem? In other words, if the problem as originally conceived was that falling prices combined with sticky wages led to above-equilibrium real wage rates, the shouldn’t an increase in productivity mitigate that problem? Employers just keep nominal wage rates at their “stuck” level, and the ever-improving workers raise the equilibrium wage rate up and up, shrinking the gap.

So to repeat, I think the explanation–at least if Beckworth/Sumner like the “productivity has grown” answer for why record-breaking NGDP hasn’t pulled us out of the recession–is internally inconsistent. If stagnant NGDP is only a problem because of sticky wages, then it doesn’t make sense (at least to me) to say, “Oh shoot, if only productivity hadn’t grown the last 2 years, we’d now be at full employment.”

This is a crucial point, so let me put it differently. Suppose there had never been any problem with AD. Instead, back in mid-2008, all of a sudden there was a huge leap in worker productivity–namely, workers back then suddenly became as productive as they are (in reality) right now. Now with sticky prices and wages, this could lead to a big spike in unemployment: The fully-employed factories are cranking stuff out, and inventories are piling up, because employees still have the same take-home pay, and the owners refuse to cut prices. So the workers don’t have enough total income to buy the higher output, at the original prices. So in this case, wouldn’t the goal would be to reduce the price level? But if so, then why in our environment, does Scott (not sure about David) think the Fed’s policies are starting to work when price inflation ticks up? (I have seen him say that on his blog; I’m not conflating “I think the Fed needs to do more to boost AD” with “I want higher price inflation.”)

(3) For my third question, I want David and/or Scott to give me their take on this graph:

Isn’t it a bit weird, if the alleged problem is one of wages and prices that are rigid downward, that both CPI and average hourly wage rates are at all-time highs? If we have a glut in the labor market, because at least one of those things (wages or prices) is stuck against a binding constraint, then why are they both moving upward? Furthermore, even the gap between the two has grown back to its level of the period during the peak housing bubble years, when there was no unemployment problem.

I think Scott may say, “When we speak of wages being ‘sticky downward,’ that’s sloppy. Actually wage contracts have built-in increases, and there is an expectation among workers that they will get raises. So it’s not that wages are flat and can’t sink to restore equilibrium, it’s worse than that: Wages are ‘stuck’ on an upward trend.”

If that is indeed his answer, then fine, but then I repeat my question from (2): If the problem is that nominal wages are rising too quickly, then wouldn’t the solution be to boost productivity? In that way, the workers could deserve their nominal wage increases. And yet, I thought we had to cite “rising productivity” as the reason for why record-high NGDP hasn’t gotten us out of the rut yet.

NOTE: I am not claiming that I’ve found actual contradictions in the Beckworth/Sumner worldview; I know there are internally consistent formal models with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed. But I’m saying from the verbal discussion of those models, I can’t keep things straight. So please enlighten us, you monetarist Keynesians you.

Scott looks to be all wrong about residential construction. He doesn’t have any idea what his numbers mean. “Homes under construction” remained strong in 2007, and didn’t begin to significantly drop until 2008. See this graph:

http://cr4re.com/charts/charts.html?New-Home#category=New-Home&chart=NHSInventory2Dec2010.jpg

and this discussion:

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2011/01/new-home-inventory-by-stage-of.html

Here’s a better version of the “homes under construction” chart.

http://cr4re.com/charts/chart-images/NHSInventory2Dec2010.jpg

And I note again — as a 2 time new home owner — that innumerable construction workers continue to be employed in a house after completion and move in, _especially_ in homes built during the peak of the boom.

Just to clarify, when I say I’m an aggregate demand skeptic, I don’t mean to deny [1] that aggregate demand exists, at least in principle (though we might not measure it well). I also don’t mean to deny [2] that it does indeed sometimes fall sharply. Further, I concede [3] that these falls are caused by human activity, and not sunspots. However, what I am skeptical about is [4] that these anthropogenic falls in aggregate demand are damaging to human welfare, and what I outright deny is [5] that Ben Bernanke can make things better if we gave him a printing press and just let the guy do his job, for crying out loud.

[I’ve added numbering for ease of reference.]

I’m not sure why you are skeptical of #4. Yes, if aggregate demand falls sharply prices and wages will eventually adjust, but this will take time, and will involve a fair amount of carnage (Kling’s recalculation story which you have recently defended requires as a premise that adjustment be a long and somewhat painful process). I can see saying that the pain is unavoidable or that alternatives would be worse, but that doesn’t mean it’s not, to quote Life of Brian, a long slow terrible process.

As for #5, I don’t think the question is whether we should give Bernanke a printing press. He already has a printing press. If the question is whether Bernanke should have a printing press, then I think Scott and Beckworth would probably say no. However, the current situation is that Bernanke does have the printing press and he won’t share and won’t let anyone else build another one (nor will he let someone set up their own mint, etc.). In that case, if you think that they way to stop the pain associated with a fall in aggregate demand is to stop the fall in aggregate demand, Bernanke is the only game in town.

Here is an answer to 4. http://mises.org/daily/3231

As for 5. Dr. Murphy doesn’t believe anyone should have a printing press and also doesn’t believe the problems can be solved by printing money. He was stating his position and not trying to give you Sumner’s or Beckworth’s positions. I’m not sure why you would find it necessary to correct any of these statements when he is spelling out his positions so as to avoid the confusion that came from his previous posts. The debate is over what follows his clarification and not the clarification itself.

Dan,

Thanks for the link. Here are what appear to be the key paragraphs of Hulsmann’s argument:

From the standpoint of the commonly shared interests of all members of society, the quantity of money is irrelevant. Any quantity of money provides all the services that indirect exchange can possibly provide, both in the long run and in the short run. This fact is the unshakable starting point for any sound reflection on monetary matters.

And it is the most important criterion when it comes to dealing with deflation. In light of the principle discovered by the classical economists, we can say that deflation is certainly not what it is commonly alleged to be: a curse for all members of society. Deflation is a monetary phenomenon, and as such it does affect the distribution of wealth among the individuals and various strata of society, as well as the relative importance of the different branches of industry. But it does not affect the aggregate wealth of society.

Imagine if all prices were to drop tomorrow by 50 percent. Would this affect our ability to feed, cloth, shelter, and transport ourselves? It would not, because the disappearance of money is not paralleled by a disappearance of the physical structure of production. In a very dramatic deflation, there is much less money around than there used to be, and thus we cannot sell our products and services at the same money prices as before. But our tools, our machines, the streets, the cars and trucks, our crops and our food supplies—all this is still in place.

Apparently Hulsmann can’t conceive of the possibility that factories might end up idle or that people might end up unemployed. But let’s leave that aside. I would note that inflation is also a monetary phenomenon. So if Hulsmann’s reasoning is correct, no amount of inflation (even hyperinflation) can affect the aggregate wealth of a society. You might think, for example, that Zimbabwe has been made worse off by its recent experience with hyperinflation. But that’s just silliness. Hyperinflation is a monetary phenomenon, and so can’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society. It’s just a coincidence that the hyperinflation coincided with a massive fall in production, increase in unemployment, widespread famine, etc.

Do Austrians really believe this? Does anyone really believe this?

Yep, it’s certainly possible for people and capital to be unemployed. I don’t think Hulsmann is denying that at all. His point is just that the appropriate solution is for these people and goods to redirect toward producing things people want, *not* (as Keynesians and neo-monetarists prefer) to trick people into blowing their money on the existing output that they don’t want (at its current process) with no price drop, prolonging this mis-match of resources.

I mean, that is what the economy is supposed to be about, right? Satisfying wants? As opposed to keeping up an imperfect metric of satisfying wants when we’re in its blind spot?

Silas,

I don’t understand how not allowing the money supply to suddenly drop by a huge amount (which is the scenario Hulsmann was considering) means that people are being tricked into blowing their money on things they don’t want. For example, the money supply did not, in fact, fall by half last night. If it had no doubt people’s purchasing decisions today would be very different. Does the fact that the money supply didn’t fall by half mean that everyone who spends money today is being tricked into blowing their money on things they don’t want?

Silas,

It’s useful to split recessionary effects into two categories. First we have primary or “real” ones which are the result of a drop in productive capacity or an expectation of that. Some would call that a “supply-side” effect.

Secondly, we have the effect of changes in the demand for money. These Hayek called “Secondary Recessions”.

What monetary disequilbrium theory proposes is that we compensate for the secondary recession. We can’t possibly do anything about the primary recession.

Think about it this way…. Suppose an ABCT bust happens and the demand for money remains the same. Each person decides that not much about the future has changed. In this unlikely situation we would get *price inflation* because there would be the same effective amount of money chasing fewer goods. But, in real recessions we often get deflation, that’s because the demand for money doesn’t remain constant, it rises. The effective amount of money therefore falls and although it’s chasing less goods prices fall too.

What we propose is to meet the demand for money with a supply of it. That supply can be provided by monetising assets that are currently being used in other ways.

That would not mean that people would be tricked in any way. It would mean that the effect of the primary recession would be a rise in prices along with unemployment in misallocated industries.

Blackadder,

Hulsmann’s argument is that inflation or deflation doesn’t cause wealth already created to disappear. Rather that it causes a transfer of wealth. For example, he says

“In short, the true crux of deflation is that it does not hide the redistribution going hand in hand with changes in the quantity of money. It entails visible misery for many people, to the benefit of equally visible winners. This starkly contrasts with inflation, which creates anonymous winners at the expense of anonymous losers. Both deflation and inflation are, from the point of view we have so far espoused, zero-sum games. But inflation is a secret rip-off and thus the perfect vehicle for the exploitation of a population through its (false) elites, whereas deflation means open redistribution through bankruptcy according to the law.”

He would argue that inflation would reward the government and politically connected at the expense of the real wealth producers. Thus inflation transfers wealth into the hands of those who will destroy future production and deflation transfers wealth into the hands of those who will further wealth expansion.

I probably made that last statement a little too simplistic and applied my beliefs to his. I’ll let Hulsmann’s words speak for themself. He said,

“With these statements we could close our analysis. We have seen that deflation is not inherently bad, and that it is therefore far from being obvious that a wise monetary policy should seek to prevent it, or dampen its effects, at any price. Deflation creates a great number of losers, and many of these losers are perfectly innocent people who have just not been wise enough to anticipate the event. But deflation also creates many winners, and it also punishes many political entrepreneurs who had thrived on their intimate connections to those who control the production of fiat money.

Deflation is certainly not some sort of a reversal of a previous inflation that repairs the harm done in prior redistributions. It brings about a new round of redistribution that adds to the previous round of inflation-induced redistribution.[18] But it would be an error to infer from this fact that a deflation following a foregoing inflation was somehow harmful from an economic point, because it would involve additional redistributions. The point is that any monetary policy has redistributive effects. In particular, once a deflation of the supply of money substitutes sets in, the only way to combat this is through inflation of the supply of base money, and this policy too involves redistribution and thus creates winners and losers.

It follows that there is no economic rationale for monetary policy to take up an ardent fight against deflation rather than letting deflation run its course. Neither policy benefits the nation as a whole, but merely a part of the nation at the expense of other groups. No civil servant can loyally serve all of his fellow citizens through a hard-nosed stance against deflation. And neither can he invoke the authority of economic science to buttress such a policy.”

Dan,

If I burn down an auto plant this doesn’t make any of the cars that have already come off the assembly line disappear, but it does make producing more cars from that plant a bit more difficult.

Obviously if you have deflation this isn’t going to vaporize goods produced before the deflation. Hulsmann’s claim, though, is that since deflation is a monetary phenomenon it won’t adversely affect production going forward either. As he says: “In a very dramatic deflation, there is much less money around than there used to be, and thus we cannot sell our products and services at the same money prices as before. But our tools, our machines, the streets, the cars and trucks, our crops and our food supplies—all this is still in place. And thus we can go on producing, and even producing profitably, because profit does not depend on the level of money prices at which we sell, but on the difference between the prices at which we sell and the prices at which we buy.”

I’ll put it to you again. The very same argument applies to hyperinflation a la Zimbabwe. If prices double over night, we still would have the same tools, machines, cars, crops, and so on. So by Hulsmann’s logic we would go on producing just as before, and would go on producing profitably, since profit does not depend on the level of money prices at which we buy, but on the difference between the prices at which we sell and the prices at which we buy.

If Hulsmann is right, then hyperinflation hasn’t reduced aggregate wealth in Zimbabwe at all, it’s just altered the distribution of wealth among the members of the society. Do you really believe that Zimbabwe’s experience with hyperinflation hasn’t made the country any poorer? That it would still have 80+% unemployment if it had been on the gold standard for the last decade?

Blackadder,

Hulsmann is not arguing that inflation doesn’t destroy productivity. He in fact would argue the reverse. He would say that inflation transfers wealth to the people who get the new money first like politicians or politically connected businesses. They in turn destroy the productive capacity of a nation.

Inflation doesn’t destroy wealth. It is the fact that inflation transfers the wealth to those who destroy wealth that is the problem. I thought that this point was clear.

Hyperinflation didn’t destroy wealth in Zimbabwe, it prevented them from creating new wealth and also caused them to consume their existing capital. There is a huge distinction here that I think you are missing.

Think about this, Austrians said the housing bubble would eventually lead to a recession and higher unemployment. Do you really think that the biggest opponents of inflation don’t take into account the problems inflation causes? You are trying to infer an opinion of monetary phenomenon that the Austrians don’t hold. They don’t suggest that monetary phenomenon doesn’t cause problems for an economy.

I really think you should reread his whole article because I have never heard any other infer the things you have from it. I’m not aware of anybody accusing of Hulsmann of the views you accuse him of holding.

One other thing. I thought this was absurd and wasn’t going to comment on it but I will just to answer what you wrote. You said,

“If I burn down an auto plant this doesn’t make any of the cars that have already come off the assembly line disappear, but it does make producing more cars from that plant a bit more difficult.”

Does inflation or deflation burn down auto plants? If not, what’s your point? If you mean that inflation or deflation causes changes in future production the Austrians would agree. So I don’t see the problem here.

Hulsmann is not arguing that inflation doesn’t destroy productivity.

I realize that. He is arguing that deflation doesn’t destroy productivity. But the argument he uses would apply equally to inflation as to deflation.

Hulsmann’s argument is basically this:

1. Deflation is a monetary phenomenon.

2. Monetary phenomenon can’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society (either in the short or long term), only its distribution.

3. Therefore deflation doesn’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society, only its distribution.

The same argument, however, can be applied to inflation:

1. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon.

2. Monetary phenomenon can’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society (either in the short or long term), only its distribution.

3. Therefore inflation doesn’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society, only its distribution.

I’m not saying that Hulsmann actually thinks that inflation can’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society. Obviously he doesn’t believe that (nor should he). What I’m saying is that his argument *does* imply that conclusion, whether he realizes it or not. So if the conclusion is false that means there is something wrong with the argument. (I would also add that the fact Hulsmann doesn’t seem to realize he’s just given an argument that, if true, would refute the entire Austrian school suggests he hasn’t thought about the issue very clearly).

Does inflation or deflation burn down auto plants? If not, what’s your point?

My point is that saying deflation “doesn’t cause wealth already created to disappear” isn’t saying much. You could believe that, and still think that deflation has a devastating effect on the economy.

Where does Hulsmann say that monetary phenomenon can’t affect the aggregate wealth in an economy in the short or long term? If you can’t show me this then I rest my case that you are putting words in his mouth.

My guess is that you didn’t understand what he meant when he said that any quantity of money provides all the services that indirect exchange can possibly provide, both in the long run and the short run. This does not have anything do with monetary phenomenon. You can’t just replace quantity of money with monetary phenomenon and act as if they mean the same thing. If you can’t see why his actual words don’t make the wild leap you think they do then I don’t know what to tell you.

Where does Hulsmann say that monetary phenomenon can’t affect the aggregate wealth in an economy in the short or long term?

Quote: “Deflation is a monetary phenomenon, and as such it does affect the distribution of wealth among the individuals and various strata of society, as well as the relative importance of the different branches of industry. But it does not affect the aggregate wealth of society. “

No, no, no, don’t try to slip out of it that way. Where does he say over the short or long term. That is what you said he said. We already know that inflation or deflation doesn’t cause aggregate wealth to disappear but where does he say that future aggregate wealth is not affected, which is what you are saying he said.

We already know that inflation or deflation doesn’t cause aggregate wealth to disappear but where does he say that future aggregate wealth is not affected, which is what you are saying he said.

Dan, are you saying that when Hulsmann claims deflation doesn’t affect the aggregate wealth of a society, all he means is that it doesn’t affect wealth produced *prior* to the deflation?

If that’s the case, then Hulsmann hasn’t offered an argument against deflation at all. No one argues that deflation is a bad thing because affects prior production. The argument is that it is bad because once the deflation occurs it will impede production. On that interpretation Hulsmann might as well have said that deflation isn’t harmful because it doesn’t cause cancer.

I’ll grant you that the Hulsmann article is very very confused (he argues, for example, that inflation can’t affect unemployment because how long workers remain unemployed depends on how long it takes them to exhaust their savings; as if inflation couldn’t affect *that*). But even I have trouble believing that the article was as bad as it would be if when Hulsmann says deflation doesn’t affect aggregate wealth he is referring only to wealth created before the deflation.

Here is what I take hulsmann to be saying.

1. That any stock of money is sufficient to handle all indirect exchange.

2. Changes in this stock of money, ie inflation or deflation is a monetary phenomenon that transfers the current aggregate wealth from one set of people to another.

3. He specifically says, “Neither policy (inflation or deflation) benefits the nation as a whole, but merely a part of the nation at the expense of other groups”

4. Inflation hides the redistribution and is “the perfect vehicle for the exploitation of a population through it’s false elites, whereas deflation means open redistribution through bankruptcy according to the law”.

5. Once the redistribution from deflation has run its course and the money supply is at a fixed amount again then it will be sufficient to satisfy all indirect exchange.

6. He says “the point is that any monetary policy has redistributive effects. In particular, once a deflation of the supply of money substitutes sets in, the only way to combat this is through inflation of the base money supply, and this policy too involves redistribution and thus creates winners and losers.

7. At no point does he say deflation doesn’t affect aggregate wealth production moving forward. He says neither benefit the nation as a whole. You seem to prefer the winners to be those who benefit from inflation and he those who benefit from deflation.

1. That any stock of money is sufficient to handle all indirect exchange.

This is true in equilibrium, but not if there is a monetary disequilibrium.

2. Changes in this stock of money, ie inflation or deflation is a monetary phenomenon that transfers the current aggregate wealth from one set of people to another.

The question isn’t whether deflation effects a redistribution of resources. No one denies that. The question is whether that is all that that deflation does. Opponents of deflation claim that deflation is bad because it impedes production going forward. If Hulsmann denies that a monetary phenomenon can impede production going forward, then he is laughably wrong. If he doesn’t deny this, then where is his argument that deflation isn’t bad for the economy?

3. He specifically says, “Neither policy (inflation or deflation) benefits the nation as a whole, but merely a part of the nation at the expense of other groups”

Again, the claim is that deflation is harmful to the economy, so saying that deflation isn’t beneficial doesn’t address that point.

4. Inflation hides the redistribution and is “the perfect vehicle for the exploitation of a population through it’s false elites, whereas deflation means open redistribution through bankruptcy according to the law”.

I doubt this is actually true (for example, I don’t think that the main redistribution brought about by deflation has to do with bankruptcies; rather the redistribution tends to be from the unemployed to those who still have jobs). But true or no, it isn’t relevant to the argument that deflation is bad because it impedes production.

5. Once the redistribution from deflation has run its course and the money supply is at a fixed amount again then it will be sufficient to satisfy all indirect exchange.

6. He says “the point is that any monetary policy has redistributive effects. In particular, once a deflation of the supply of money substitutes sets in, the only way to combat this is through inflation of the base money supply, and this policy too involves redistribution and thus creates winners and losers.

Suppose that there is a monetary contraction. This will lead to a period of adjustment as prices and wages fall to match the smaller money supply.

Now it’s perfectly true that once this adjustment process is completed it would no longer make sense to try and increase the money supply back to former levels. That would just create a new disequilibrium, and require a new adjustment process. On the other hand, if you reverse a monetary contraction before the adjustment process is complete (or, better, prevent the contraction from happening in the first place), then you avoid having to make the adjustment in the fist place along with all of the attendant pain, suffering, and lost economic output.

7. At no point does he say deflation doesn’t affect aggregate wealth production moving forward. He says neither benefit the nation as a whole.

Interpreting Hulsmann has not claiming this is not only strained, it makes his article pointless, as it means he does not even address the typical case against deflation. By that logic I could say that cancer isn’t bad for your health, because no one dies of cancer until after they get cancer, and I never said cancer didn’t affect your health going forward.

1. The Keynes argument. The Austrians are right but that only applies to an economy in perfect equilibrium which we never have. Hasn’t this argument been refuted enough by now?

2.Hulsmann doesn’t deny that a monetary phenomenon can impede production going forward. He would say let the deflation run its course instead of trying to combat that monetary phenomenon with another monetary phenomenon, inflation.

3. see 2.

4. How is your response not open redistribution that follows the rule of law?

5 and 6. I know that is what you believe. I said that you would probably favor the redistribution through inflation where he would favor the redistribution through deflation. Just because you think it is the best decision to inflate doesn’t mean it is any less a monetary phenomenon or any less redistributive.

7. His article isn’t pointless, it is just lost on you.

Dan,

You need to try and get your mind around the fact that avoiding deflation is not the same as inflation. I am not saying that the redistribution of inflation is preferable to the redistribution of deflation. If you act to prevent or counteract a monetary contraction before the adjustment process occurs, you prevent the redistribution from happening.

The money supply did not fall by half last night. If it had, and this fall wasn’t reversed, then there would have been deflation with it’s redistributionary consequences. Does the fact that this deflation didn’t occur mean that we actually had a massive inflation induced redistribution in the last 24 hours?

Likewise, if the money supply had contracted last night and then was restored to it’s previous size this morning, that would not mean that we had experienced huge inflation or redistribution. Prices and wages hadn’t adjusted to the smaller money supply, and by restoring the previous level you prevent this adjustment from ever having to happen.

I consider Hulsmann’s article pointless on your interpretation, because it does not address the arguments made against deflation. Suppose someone wrote an article claiming to prove that inflation wasn’t harmful, but didn’t address any of the Austrian arguments in this regard. How would you describe it?

The inspiration for much of the quasimonetarist thinking here is not Keynes but Hayek.

You need to get your mind around the fact that the only way to counter deflation is with inflation. Maybe you don’t like to call it inflation and we can have one of those awesome semantical arguments but it is inflation just the same.

There is going to be redistribution of wealth during any monetary phenomenon. If deflation sets in can you explain how it is that you are going to correct it without 1. Inflating the money supply and 2. How do you make sure that once you start inflating the money supply that it has no redistributive effects.

Austians sometimes define deflation and inflation as a decrease or increase in prices and sometimes as an decrease or increase in the money supply. Under either definition it is simply not true that the only way to prevent deflation is to have inflation. It’s not true that the only alternate to falling prices is rising prices; price stability is also a possibility. It is not true that the only alternative to a decreasing money supply is an increasing money supply; the money supply could remain unchained.

Austrians sometimes talk as if any additions to the money supply are equivalent to an increase in the money supply. But that is incorrect. Imagine a sink with the water turned on and the plug up. Water is being added to the sink from the faucet, but it does not follow that the total amount of water in the sink is increasing (because water is also flowing out of the sink via the drain).

Why paint what I say in ways that obviously nobody would agree with. I didn’t make the case you implied I did.

I never said, that the only alternate to falling prices is rising prices. That would be stupid to say especially coming from a Rothbardian. What I said is that the only way to stop deflation from running its course is inflation. I would prefer stability over either but if we experience deflation I would rather let it run its course than inflate the money supply back up.

You said, “Imagine a sink with the water turned on and the plug up. Water is being added to the sink from the faucet, but it does not follow that the total amount of water in the sink is increasing (because water is also flowing out of the sink via the drain). ”

I agree that you can increase the money supply and drain from other areas at the same time. The question is how do you do this without redistributive effects?

Any monetary policy is going to have redistributive effects and Hulsmann would favor deflation’s over inflation’s effects. You are in the opposite camp but want to believe that you are not inflating or redistributing without explaining how this is even possible.

Finally, how do you define inflation? I define it as increasing the money supply, which includes increasing it after or while it is falling. Prices rising can be a consequence but I wouldn’t call it inflation. Prices can rise for many reasons but I don’t have a problem with saying price inflation to describe prices rising from inflating the money supply. I define deflation the same way but obviously falling money supply.

The way you talk I could just as easily argue that it isn’t deflation if the money supply is falling back to where it was before an increase. So if Bernanke doubles the money supply tomorrow and then cuts it back in half the next day, we didn’t have inflation and then deflation of the money supply. We just had a stabilization of money supply but I still wouldn’t be able to show how this kind of action has no redistributive effects.

The way you talk I could just as easily argue that it isn’t deflation if the money supply is falling back to where it was before an increase. So if Bernanke doubles the money supply tomorrow and then cuts it back in half the next day, we didn’t have inflation and then deflation of the money supply. We just had a stabilization of money supply but I still wouldn’t be able to show how this kind of action has no redistributive effects.

Ask yourself: how is it that a decrease in the money supply is supposed to create redistributive effects? According to Hulsmann, “[f]irms financed per credits go bankrupt because at the lower level of prices they can no longer pay back the credits they had incurred without anticipating the deflation. Private households with mortgages and other considerable debts to pay back go bankrupt, because with the decline of money prices their monetary income declines, too, whereas their debts remain at the nominal level.”

None of this is the work of an instant. You have to wait for prices to adjust, for companies to default and go bankrupt, etc. If the monetary contraction is reversed before these adjustments occur, then it will be as if the original contraction never happened. Prices won’t need to adjust downward, firms won’t go bankrupt, etc. In short, the redistribution that would have occurred if you had let the deflation “run its course” won’t happen. Nor will there be any redistribution associated with the restoration of the money supply to its original level, since prices, wages, etc. are already at the level appropriate to that quantity of money, and hence no adjustments are required.

I understand that you believe that. I just don’t know how you could prove this. For example, if the Fed wants to expand the money supply now it typically goes out and buys assets from different favored companies. How would you do it so that there is no redistribution?

I understand that you believe that.

You understand that I believe what? That I believe Hulsmann’s description of how deflation causes redistribution is accurate? Do you not believe that?

What? Yea I believe Hulsmann is correct.

I thought your position was that you could increases the money supply to prevent or fight deflation without redistributive effects?

If I’m wrong here then I’m not sure what your view is. If that is your view I’m asking you to show me how you would increase the money supply with no redistributive effects?

The timing issues aren’t relevant. The “official” date of the beginning of the recession was December 2007. Just because the NBER committee picked that date doesn’t mean that unusually great misallocations of resources weren’t causing greater structural unemployment and reduced real output growth before that point.

Of course, money expenditures were also falling below trend at that point too.

A slight slowing of money expenditure growth will almost certainly cause modest disruption. Whether or not the NBER committee calls that a recession or not isn’t too important. Is it bad enough to count it as an “official” recession? An unusually large shift in the composition of demand will almost certainly cause slightly higher structural unemployment and slower growth in productive capacity. Will the NBER committee call this a recession? How bad must it be before they call it a recession? If it gets progressively worse over time, when did they say it became a recession?

A large drop in the growth path of money expenditures, that to this day has not been reversed, will almost certainly cause a terrible recession. For it not to cause such a recession, prices and wages would both need to rapidly drop to the same amount–to a new lower growth path.

Now, it is possible to return to that growth without any drop in prices or wages. If the growth rate resumes (as it has) all that is requires is that prices and wages grow more slowly than money expenditures. Then, real expenditures will gradually recover. The real quantity of money will grow more and catch up to whatever real demand to hold money that exists.

Yes, there is no doubt that the problem is a sticky growth path for wages and prices, and not merely that wages don’t drop.

With a large drop in money expenditures, wages and prices would need to drop to avoid a disruption in output. However, even if money expenditures grow more slowly, getting everyone to shift to a new growth path of wages and prices is going to disrupt production.

The other side of that coin is inflationary equilibrium. A higher growth rate of money expenditures doesn’t result in persistent shortages of output and labor, with firms and households constantly playing catch up. Oh, shortage, raise prices and wages from their current level. Oh, still a shortage, raise them more.

With the Fed at least hinting that they plan on 2% inflation forever, there is further reason to expect a sticky trend.

How, your position must be that the shift in demand composition resulted in a decrease in productivity capacity and increase in structural unemployment to match the current drop in output. And so, there was never any need to reduce prices or wages. The reason wages and prices continue to rise is because if they didn’t, there would be shortages of goods and services and labor. If money expenditures had been maintained, then the current level of prices and wages would have resulted in large shortages and prices and wages would have needed to rise even more. And, of course, if money expenditures resturn to trend, then there will be a very high rate of price inflation and wage inflation.

I don’t believe this is true.

There is a mixture of problems. Prices and wages have hardly moved away from their past trend. Money expenditures are 13 percent below. The shift in the allocation of resources, and really, just permanent losses of specific human capital and capital goods has reduced the growth path of the productive capacity of the economy. Strucutual unemployment is higher.

In my view, real expenditures are below a somewhat depressed productive capacity. The unemployment rate is above a somewhat increased natural unemployment rate.

I don’t think the other quasimonetarists disagree much. Sumner has been claiming that if nominal expenditures had stayed on trend, the structural unemployment would mostly be over now. Maybe.

Please keep in mind, your arsenal of arguments again targeting real output or unemployment don’t apply to quasimonetarists.

Bill (if I may),

Two things: First, on the NBER stuff, I just want to be clear I’m asking Scott to reconcile his two seemingly contradictory positions. When Arnold Kling and I say that unemployment is (partially) due to the need to reallocate workers out of housing construction, Scott thought he had blown us up by showing that housing starts (and completions) peaked in early 2006. So if that’s how he feels, then how can he claim that the fall in housing construction is what (partially) caused the late 2007 recession?

Second, if you say that the problem is that money expenditures aren’t growing fast enough, relative to prices and wages, then you agree with me that–other things equal–you and Scott should be rooting for flat CPI? And yet, I know that Scott has said that he is encouraged when he sees CPI inflation picking up. So at best, that is because of an indirect argument, right? Something like, “If people think Bernanke is going to pump in more, then CPI starts rising, which in itself is a bad thing, but on net is a good thing because maybe money expenditures will rise even more”?

I admire your desire to understand your opposition and not misrepresent them before you offer a final analysis. Your opponents dare not do so.

What we’ve got here is failure to communicate. Some men you just can’t reach.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fuDDqU6n4o&feature=related

Bob, are you INSANE? Are you really saying we shouldn’t sacrifice to appease the NGDP God? Isn’t that pretty much guaranteed to provoke Him to erupt and rain brimstone down on us???

Stupid snark unworthy of you. Lets just pretend nominal shocks have no affects to please your morality gods.

How dare you! There is no level of stupid snark that is unworthy of Silas!

I must always remind myself that the NGDP theory is based on an illusion.

Regarding Productivity….

I know that in the past in Britain productivity has often increased during recessions. It has also increased when the rate of unemployment benefit (dole) is raised.

This is because of the marginal decisions being made. An employer lays off the workers that produce the smallest marginal increase in his profit. Those employees are the least productive. Once they are unemployed they no longer play a part in the productivity calculation, but those still in employment do so the average productivity rises. This isn’t caused by new machinery or better methods, it’s caused by the least productive being put out of work and their figures leaving the calculation.

The same thing happens when unemployment benefit is raised. For many years France had much higher productivity per person that Britain, but GDP was similar and growth a little lower. The reason for that was that France’s unemployment rate was higher.

Aggregate Demanders! I like it.

And now my 2c. Yes, the increased demand for money, the aggregate demamnders keep telling us about is real. Except that.. “demand for money” is .. demand for future goods. See? So, how this can be fixed by increasing the supply of *nominal* money?

Besides the AD-ers take for granted that amount of spending in, say, 2002-2008 was about right and it was just it composition was wrong and lead to a housing bubble. Was it? Says who? And most importantly, why? But, I digress

So what would be the optimal response to an increased “demand for money”? By the way, is anyone going to deny that this is just an increased demand for future goods?

Well it’s easy, the economy should restructure (recalculate itself) as to produce less current goods and more future goods. Yes, it means more investments. Except that this would be investments of different kind based on lower relative wages and princes and not on “Maestro’s” cheap money. And, BTW, how USA handled its’ 1919-1920 Forgotten Depression.

Besides the AD-ers take for granted that amount of spending in, say, 2002-2008 was about right and it was just it composition was wrong and lead to a housing bubble. Was it? Says who? And most importantly, why?

The prior trend in nominal spending is important because it is an indication of people’s expectations of where spending would be after 2008. Those expectations get built into things like wage demands, loans and contracts, etc.

For example, suppose I buy a new house and then, shortly afterward the money supply contracts unexpectedly. Prices fall by 50%. Wages fall by 50%. The amount of my loan, however, is measured in nominal terms. It doesn’t fall. In fact, in real terms, the amount of my loan has just doubled. Ditto if I’ve just agreed to buy X tons of ball bearings for price Y, and so on.

These problems don’t arise because I have made a malinvestment. They arise solely because of the unexpected monetary contraction.

You are not answering my question. So, I’ll be fair. I will not answer yours.

Vasile,

First, I didn’t ask you any questions, so I don’t know what you are talking about.

Second, your question was why it was important for nominal spending to continue its 2002-08 trend. My comment did address that question. If you find my answer unsatisfactory, you might try and say why (or not, whatever floats your boat).

> Except that.. “demand for money” is .. demand for future goods. See?

Demand for money isn’t demand for future goods.

Money is one piece in a portfolio of assets a person has. They may choose to increase their holding of money while reducing that of other assets.

A rise in demand for money doesn’t necessitate a fall in the natural rate of interest, though both may occur at the same time.

> So, how this can be fixed by increasing the supply of *nominal*

> money?

I’m not quite sure I understand your criticism here. When the demand increases the supply can be increased too. Not just the nominal value of the supply, but it’s real value too.

We’re not suggesting have $X of backing assets and using that to produce a stock of 2* X$ of money. We’re suggesting drawing backing assets in from other uses and using them to issue new money.

> Demand for money isn’t demand for future goods.

Maybe, if one is a money fetishist. Can’t think of much else. Pretty much the usual definition of money (means of exchange) is that.. money is demand for future goods.

> Money is one piece in a portfolio of assets a person has.

And assets this scenario are valued because of their consumer value?

Anyway, I wasn’t trying to address subtler points as related to changes in asset portfolio. More cash, less treasuries or the other way round.

I was responding to the point that problem the USA/World economies are facing now is a lack of aggregate demand. Unless I’m mistaken moving moving money from treasuries and back, which (treasuries) at often treated as cash of big denominations has a negligible influence on aggregate demand for consumer goods.

> Maybe, if one is a money fetishist. Can’t think of

> much else.

To be clearer, a rise in demand for money doesn’t mean a net rise in demand for future goods if the demand for other types of savings falls.

> Unless I’m mistaken moving moving money from

> treasuries and back, which (treasuries) at often

> treated as cash of big denominations has a

> negligible influence on aggregate demand for

> consumer goods.

I never know where Post-Keynesians are going to crop up these days.

Yes, treasuries are sometimes used as “large denomination money” (though I believe it’s normally T-bills that are used that way). But that isn’t their only use, and other types of debt are much less liquid than treasuries.

Converting bond-like debt into money substitutes certainly can help “aggregate demand” because it can satisfy the demand for money.

The arguments Post-Keynesians put forward that lump all debts into “Savings” are merely justifications for writing off money as a source of economic problems. They are a way of arguing for fiscal stimulus which can be coupled with redistribution.

> To be clearer, a rise in demand for money doesn’t mean a net rise in demand for future goods if the demand for other types of savings falls.

Good to have this cleared out. And well it was funny to be considered a Post-Keynesian for once in a while.

That I do not approve of any form fiscal stimulus will not help, I suppose?

And yes the printing money which took place during the boom is the cause of the problems. Just curious, this makes me what?

Vasile, you are an exotic and rare hybrid.

If you truly think that bonds are equivalent to money as Post-Keynesians do then how can you argue that “the printing money which took place during the boom is the cause of the problems”? What happened during the boom is normal monetary operations, the Fed created money by buying bonds. If that doesn’t create money now then how did it create money then?

You can demand all you like, but if you don’t have FRNs, then you are shit out of luck.

1. NGDP did fall in the last quarter of ’07, if I recall correctly. Then, by January ’08, the Fed began to take extraordinary measures, such as the special auction loan facility. Somewhere around that time they also started allowing non-commercial banking institutions to take Fed loans.

2. The graph shows GDP still below it’s trend line. That meaning it’s below where it would have been without the recession.

And do you have evidence for a big spike in productivity as a cause of unemployment? And why would we have seen the economic distress we did associated with increasing disinflation, and reversing with reinflation?

3. CPI is lower than trend and the wage line demonstrates stickiness. CPI is below where it would have been if not due to the recession-related disinflation.

Vasile,

Delayed consumption is like justice in this case, in which “Justice delayed is justice denied.” This lowers AD, causing GDP to fall and increased unemployment.

Go to a locally owned store and tell the owner not to worry, because people are merely delaying more of their purchases. In the meantime, he has falling profits and may go bankrupt.

Mike, how about you doing the opposite? Rush to a neighborhood, maybe even yours, and tell everybody to go out spending because the local store owners had problems.

It’s not from the philanthropy of their customers that the store owners should extract their profits.

And no, delayed consumption is not like delayed justice. It happens all the time. (Nobody’s spending all their income the moment they put their hands on it) It just happens at different times in different proportions. So, during the the boom years the current consumption raised to unsustainable levels and now people have to step back. For a while.

And that’s OK, because.. because.. because… you can spend your way out of a recession no more than you can eat your way out of a famine.

Vasile,

At the risk of bumping my head against the wall of your religious beliefs, I point out that economies are just networks of trades. When the economy slows, meaning the volume and/or average value of trades drop, obviously it means spending drops and unemployment rises. Unemployment rises, primarily due to sticky wages and prices, as many economists have it, and the evidence seems consistent with that.

So, to recover, spending must increase and if the private sector won’t do it, the government should. Someone has to spend for there to be an economy at all. Otherwise, you have idle workers and capital, as we have now, and it’s needless.

Prices and wages will not adjust to bring back demand. There is almost $2 trillion dollars in money that could be used to capital investment sitting on the sidelines, due to a lack of rising demand for their products/services.

When people spend when we’re below capacity, it’s a very good thing as it’s literally more economic activity. It’s not philanthropy, as it benefits most people. Even the wealthiest can benefit from an increase in demand for goods and services.

Bob,

Scott favors faster growth in money expenditures, not higher inflation.

However, he believes that if money expenditures continued to grow as he prefers ,then there

would have been higher CPI inflation.

And, moving money expenditures to a higher growth path (and a 5% rate) would also result in higher CPI inflation.

He has written from time to time that the less of this increase in money expenditures that takes the form of price inflation and the more that takes the form real output growth the better.

And so, given current growth of NGDP, flat CPI is better than faster CPI inflation.

However, a return of money expenditures to trend would probably result in faster CPI inflation.

I always give Sumner a hard time about treating the faster money expenditure growth as being equivelent to its undesirable likely side effect;, more rapid CPI inflation. He always agrees and explains again what I have said above.

This is a difference between quasimonetarists and Keynesians like Krugman. They seem to think that we need higher expected inflation (presumably with some follow through and actual inflation) to reduce real interest rates, to get money expenditures to rise.

Generally, quasimonetarists don’t see it like that. We don’t deny this effect, though usually focus on higher expected inflation reducing real money demand. Still, our emphasis is increase in the quantity of money, more money expenditures, more inflation and real output growth some combination. The less the inflation and the more the real output growth the better.

And all of this is about reversing the decrease in the growth path of money expenditures. Quasimonetarists dont’ think more money expenditures is always better, and instead, favor keeping them on a steady growth path. But, that means if money expenditures shift away from that growth path, they should be put back. And we are in massive downward shift and a past due need to get them back up.

Quasimonetarists are like monetarists but with changes in the quantity of money to offset changes in velocity. Keep MV on a steady growth path. If V were more or less constant, it would have the exact same consequence of keeping the quantity of money growing at a slow, steady rate.

However,

Bob:

Don’t you feel any obligation to correct the errors of all of these amateur Austrians?

If the nominal quantity of money doesn’t rise to accomodate an increase in the demand to hold money, and instead, the level of money prices and wages fall enough to accomodate it, then real capital gains on money holdings motivate people to expand their real expenditures on consumer goods or capital goods. The process of lower money prices (including wages) and a higher real quantity of money is somehow getting people to expand their real expenditures.

With an outside money, this transfers wealth to people to the degree they hold their wealth in the form of outside money. I have no idea why anyone would assume that such people are especially worthy compared to those who hold equities.

At the same time, to the degree this is unexpected, those creditors benefit at the expense of debtors. If it was expected, it was already taken into account in nominal market interest rates. With inside money, this same effect occurs. Ultimate creditors who hold inside money benefit at the expense of utlimate debtors who borrow from banks. To the degree the losses to debtors are too great, then there is a default, and the creditors can grab more capital from debtors, including banks. But there are also reorganization costs that come at the expense of creditors.

What is good about this?

An institutional framework that avoids inflation or deflation, and is expected, does make holding zero interest hand to hand currency a bit less attractive, but other than that, it doesn’t benefit debtors at the expense of creditors. They pay more interest than otherwise.

The notion that an unexpected deflation is good because it benefits especially worthy people is approximately crazey.

Of course, this notion that inflation benefits the politically connected is very doubtful. The most plausible version is that government creates new money and spends it as a source of revenue. There is some truth in this, but not a whole lot. I don’t think government would spend less without money creation by the amount of the money creation.

Treating banking as if people getting bank loans funded by money issue are getting some special benefit relative to those who obtain loans funded by CDs or loans from finance companies or who sell bonds or commercial paper is a serious exageration. If we imagine some banks solely issuing CD’s and others issuing checkable deposits, the notion that the ones issuing checkable deposits are especially benefiting by money creation is also implausible. From the individual banks perspective, there are various sources of funds that they pay for.

Bob: Don’t you feel any obligation to correct the errors of all of these amateur Austrians?

Do you mean, do I feel obligated to spend an hour every day refereeing the comments on this blog–when I am happy if I get to bed at midnight doing all my other paying work each day? That’s the funniest thing I’ve read in the comments in a long time…

Of course, this notion that inflation benefits the politically connected is very doubtful.

So why were central banks created? Is it just a bunch of reformers honestly trying to help people, and they maybe made a mistake?

Do you mean, do I feel obligated to spend an hour every day refereeing the comments on this blog–when I am happy if I get to bed at midnight doing all my other paying work each day? That’s the funniest thing I’ve read in the comments in a long time…

If I didn’t know better, it appears Bill was complimenting you.

After all, you have been correcting the quasi-monetarists and Keynesians all over the place in recent days, with fairly widespread attention. Why aren’t you correcting every person in the world? That is the minimum expectation now. You’re now supposed to be on a rock and roll tour with no stops.

@Bill_Woolsey

With an outside money, this transfers wealth to people to the degree they hold their wealth in the form of outside money. I have no idea why anyone would assume that such people are especially worthy compared to those who hold equities.

Really? You honestly can’t think of any reason whatsoever?

What about the fact that they held back from consuming unsustainably, and from making stupid or brittle investments? For example, someone who didn’t get sucked into the home-buying “it always goes up” frenzy. You can’t think of a single reason why a good market would end up allowing him more consumption once reality sets in?

Or maybe you did consider that, and rejected it out of hand, not even worthy to put up as a strawman?

Bob:

OK, I am sure you are busy.

I have a big pile of papers to grade now.

Silas,

There are many ways to hold back from consuming unsustainably or else avoiding making brittle investments other than accumulating currency and putting it in a safe desposit box.

What about people who borrowed in a manner that would be sustainable? They would earn enough

future income to pay their debts?

I think those who purchased equities in well managed firms that were producing whatever it is that you think failed to expand enough during the boom are deserving. (Maybe a capital maintenance servicing firms.)

Anyway, your attitude is instructive. My focus is on coordination. That people who make bad investments lose money is important. Turning good investments into bad investments so that those who held large currency balances can make big real capital gains has little benefit.

More fundamentally, investment can provide returns, but it involves risk. Trying to make money into an imaginary risk free haven is a mistake. It only works to the degree that money prices and wages are sticky, which makes it disruptive. If prices and money wages were all prefectly flexible, then the risk of real capital loss would be obvious.

Has it at least crossed your mind that if there is a temporary increase in money demand, and the level of prices and wages fall enough to clear markets, then when the temporary increase goes away, there will be inflation and real capital losses on money holdings? Any creditor who failed to account for this by insisting on higher nominal interest rates will share in the loss, right?

There are many ways to hold back from consuming unsustainably or else avoiding making brittle investments other than accumulating currency and putting it in a safe desposit box.

Not if you’re already buying everything you want to buy with money, and you regard the remaining investment opportunities as stupid.

What about people who borrowed in a manner that would be sustainable? They would earn enough future income to pay their debts?

Yes, they would.

I think those who purchased equities in well managed firms that were producing whatever it is that you think failed to expand enough during the boom are deserving. (Maybe a capital maintenance servicing firms.)

Yes, they are deserving. And, when “money demand” increases, such firms will be able to hold their value and pay returns reflecting such a wise decision, since they are making what people want when few others are.

Turning good investments into bad investments so that those who held large currency balances can make big real capital gains has little benefit.

Sure, if the investments were really good. But if people aren’t buying the output, and their financing isn’t set up to handle such dry spells, then in what sense was the investment good? People who _prevent_ real capital from going into wasteful projects (by holding onto their money) are providing a valuable service, just as surely as speculators who bid up futures in correct anticipation of a shortage. Or do you think *that* is wasteful too, since the speculators are just holding financial assets and betting on gloom (as dollar hoarders are)?

More fundamentally, investment can provide returns, but it involves risk. Trying to make money into an imaginary risk free haven is a mistake. It only works to the degree that money prices and wages are sticky, which makes it disruptive.

It _would be_ disruptive, if such hoarding didn’t provide a valuable economic signal, the same way that speculators do. Saying that it would be nice to eliminate this pesky premium on money is no different (and no less vacuous) than saying that it would be nice to eliminate this pesky premium on oil that speculators are bidding into the price. And the latter, like hoarding money, is risky, but unlike money, does not involve sticky prices. So I don’t see the supposed disruption.

If anything’s disruptive, it’s printing money to the point that people have to buy whatever’s available now, no matter how little utility they assign to it.

Has it at least crossed your mind that if there is a temporary increase in money demand, and the level of prices and wages fall enough to clear markets, then when the temporary increase [do you mean “decrease” here? –SB] goes away, there will be inflation and real capital losses on money holdings?

*Genuinely* temporary increases in money demand do no such thing and don’t require printing money, nor do they cause such wild swings — these are handled nicely by credit cards and checking accounts, which allow people temporary liquidity, backed by some other person’s savings.

This is not the case for what we are seeing right now, with more long-term money demand incrasing, which signals a preference *not* to buy things now, and to regard current investment opportunities as bad. If this turns around, and the economy finds better uses for capital and turns out better goods, then people who hoard through those periods will then see a loss — that’s exactly how it’s supposed to work.

There are many ways to hold back from consuming unsustainably or else avoiding making brittle investments other than accumulating currency and putting it in a safe desposit box.

That’s the crux of the issue. Austrians hold that central bank inflation through the loan market (credit expansion) prevents market forces from preventing unsustainable consumption and “brittle” investments. This is because credit expansion (even if it is carried out in order to target a particular growth in NGDP which will satisfy reluctant central bank supporters) will nevertheless affect market interest rates from where they otherwise would have been had true savings been the only source of investment funds, and hence distort the market’s capital structure in the Hayekian/Misesian tradition.

Hence, quasi-monetarists, monetarists, and Keynesians actually encourage unsustainable consumption and malinvestment, for that is exactly what free market interest rates prevent “naturally” in the absence of continuous central bank induced credit expansion!

The only way out of this dilemma, that is, reconciling the desire for inflation, but not the unsustainable consumption or malinvestment that comes along with the traditional channel if inflation which is the loan market (credit expansion), is for quasi-monetarists to advocate for the central bank to literally mail checks directly to every American citizen, in such a manner as to induce them to spend however much is consistent with whatever target quasi-monetarists feel they are knowledgeable enough to know should be!

Bill Woolsey,

Do you disagree with this statement by Hulsmann,

“In short, the true crux of deflation is that it does not hide the redistribution going hand in hand with changes in the quantity of money. It entails visible misery for many people, to the benefit of equally visible winners. This starkly contrasts with inflation, which creates anonymous winners at the expense of anonymous losers. Both deflation and inflation are, from the point of view we have so far espoused, zero-sum games. But inflation is a secret rip-off and thus the perfect vehicle for the exploitation of a population through its (false) elites, whereas deflation means open redistribution through bankruptcy according to the law.”

I think everybody realizes that deflation and inflation both cause misery for a set of people but I personally find the primary benefactors of inflation to be the people who get the new money first like Goldman Sachs and politicians at the expense of the people who never see the new money like the retired or poor. I don’t think I have heard a professional Austrian suggest that inflation doesn’t benefit the political and politically connected.

I also find it to be wrong to fight one monetary phenomenon with another like fighting deflation with inflation. I don’t presume to be an authority on these matters but I’ve read arguments from Hulsmann and Salerno and arguments from Horowitz. I find the 100% reserve side presents a more satisfactory solution but I wouldn’t care if the world went to free banking compared to what we have now.

You say

“This is a crucial point, so let me put it differently. Suppose there had never been any problem with AD. Instead, back in mid-2008, all of a sudden there was a huge leap in worker productivity–namely, workers back then suddenly became as productive as they are (in reality) right now. Now with sticky prices and wages, this could lead to a big spike in unemployment:”

I cannot imagine this situation without refering to AD. If AD is sufficient, an increase in productivity can only increase demand of labor. If AD falls, Employers will fire workers and readjusted them to expected AD. How can you imagine a reaction of employers without thinking in AD?

Very sophisticated

I don’t think the losers from unexpected inflation are that hard to identify.

I think it is pretty obvious that many people fail to correctly identify the loses

from a deflationary policy. I can read lots of people who appear to think that

the only losers are people who made malinvestments.

Captain Freedom:

I don’t believe that my level of consumption during the housing boom was unsustainable.

But I didn’t hold large amounts of currency. I just didn’t borrow that much.

I didn’t borrow money against my house for consumption (or any other purpose) when

its price peaked about 4 years ago.

My equity rose, and then fell, with little impact on my consumption.

I didn’t buy many construction stocks, lumber stocks, or anything.

Again, all without accumulating large quantities of currency and putting it in my safe deposit box.

Bill,

I don’t believe that my level of consumption during the housing boom was unsustainable.

I’m sorry if my post made it seem like I was implying your consumption was unsustainable. I didn’t mean that, and I apologize.

What I tried to say when I spoke of “unsustainable” consumption is that the capital structure of the economy could not facilitate the total economy wide consumption that was taking place during the real estate boom.

I thought that the context of this thread was the aggregate economy, since we are all talking about aggregate demand, aggregate spending, aggregate consumption, CPI, unemployment, etc. So when I said “unsustainable consumption”, I didn’t mean an individual going into deep debt to finance a consumption binge, I meant the capital structure of the economy could not support the aggregate consumption that was taking place.

My main argument is that if one is going concerned about unsustainable consumption and malinvestment, and they say they can fight against it, then the other goal of targeting NGDP with inflation via credit expansion will necessarily operate against the first goal, which was preventing overconsumption and malinvestment.

The Austrian position is that inflation via credit expansion causes overconsumption and malinvestment, through no fault of any market participant, because they simply do not know what the true market rate of interest really is, since it is set by the Fed’s inflation, not the market.

Even if every individual in the economy were highly intelligent, and financially prudent, it cannot prevent them from making “mistakes” (“mistakes” meaning investment and consumption patterns that while rational and profitable at the time, they are not sustainable over the total investment horizon, on account of the aggregate economy, which nobody knows what is supposed to look like, cannot sustain it). This is because neither investors nor consumers know what the true market rate of interest really is. It is distorted by credit expansion, which is the very means by which monetarists, quasi-monetarists, and Keynesians alike all advocate in order to increase the money supply and hence aggregate demand (NGDP).

As a result, investment and consumption do not “gel” with each other.

In short, wanting to target NGDP with inflation via credit expansion, and wanting to avoid overconsumption and malinvestment, are contradictory desires. You cannot have both. You can only have one or the other.

This is why I said that only way out of this is to advocate for inflation not via the loan market, but through direct government spending (which quasi-monetarists and monetarists are against, Keynesians are for), or mailing out newly created dollars to the public directly from the printing press (which I am sure none of you would actually support).

But I didn’t hold large amounts of currency. I just didn’t borrow that much.

I didn’t borrow money against my house for consumption (or any other purpose) when

its price peaked about 4 years ago.

My equity rose, and then fell, with little impact on my consumption.

I didn’t buy many construction stocks, lumber stocks, or anything.

Again, all without accumulating large quantities of currency and putting it in my safe deposit box.

Well, to be fair, not everyone receives a relatively low risk income from government financed by the taxpayers. Your willingness to hold lower cash balances may have something do to with the fact that your expectation concerning future income is relatively stable and secure compared to others whose incomes are more uncertain. People who expected home prices to definitely be higher in the future had incentives to not hold large cash balances because they thought their future income was more secure.

So you are one of the more wise folks who only held a lower cash balance, but did not take any additional risks. Others not so wise not only held lower cash balances, but exposed themselves to high levels of real estate risk. Central planners, including the Fed, encouraged this latter risk. It’s easy to say now that they should not have done that, but they did, and so any proponent of Fed intervention has to explain why people who are so wrong so often have to maintain control of something so important.

But this is all neither here nor there.

The fundamental issue here that I think bears repeating and continued emphasis is that one cannot logically be in favor of reducing overconsumption and malinvestment, while at the same time wanting inflation via credit expansion in order to target a NGDP number. It is impossible to do both.

…and I totally screwed up the italics.

Sorry for the confusion, if any. The first sentence is supposed to be italicized. The next 9 paragraphs are supposed to be normal as they are my statements.

1. NGDP growth slowed steadily. It was lower in the first half of 2008, then in 2006 and 2007. That slowdown in demand helped slow RGDP growth. Because of the slow growth in overall demand, the fall in housing construiction (and autos due to high oil prices) was not fully offset by gains elsewhere. Hence RGDP was flat in the first half of 2008. Housing and autos declined, other output rose, but only about the same amount. Flat RGDP is a very mild recession.

2. I don’t understand why you think the rise in productivity solves the sticky-wage problem. The rise in productivity does help boost output, but it doesn’t put people back to work. If national income is barely higher than two years ago, and people who are employed make often make more than two years ago, and profits have risen due to productivity, then as a matter of sheer arithmatic won’t there be fewer people employed?

3. Follow up to previous example. NGDP is $10, and each of ten workers ge s a dollar in wages. Now they negotiate a 10% wage increase, in anticipation of 10% more NGDP. So wages rise to $1.10. Now there is only enough NGDP to emply nine workers, because NGDP unexpectedly stayed flat at $10. And that is true no matter how high productivity rises. Obviously the real world was more complex, but that’s what I see as the flaw in your logic.

Scott,

Thanks for the replies. Quick responses:

On (1): So housing construction has nothing to do with it, right? If NGDP had grown at the same rate through early 2008, then RGDP wouldn’t have gone flat? So rather than having two explanations–a real one for the mild recession and a nominal one for the sharp recession–you have one explanation, I think. Specifically, NGDP slowed in early 2008, so there was a mild recession, and then when NGDP crashed, there was a bad recession. Right?

On (2) – (3): You are misunderstanding me. I said right in the beginning that rising productivity would hurt things, if one thought people needed to spend enough to “buy all the products” to keep everybody employed. But my point was, in that case, you should be rooting for CPI to fall, and yet you don’t.

Last point–not to Scott, but to people who thought I was an idiot for saying Scott would think rising productivity would hurt things–I told you so.