Murphy Defends Tyler Cowen (Sort of)

[UPDATE below.]

Actually that is my cheap attempt to get your attention. Since Tyler apparently contradicted himself (which we all know is always apparent but impossible to prove) on this point, you could argue that I am attacking him.

Anyway, a bunch of people have been jumping on Tyler for the hypothesis in his new book that the US economy has “stagnated” since 1973. (Note that I haven’t read the book, or even a good review of it; I’m going entirely by the sniping the guys at EconLog are launching.)

Here’s Bryan Caplan:

I completely agree with Arnold when he remarks:

I personally do not think that the stagnation hypothesis can survive the thought experiment in which you offer somebody the choice between (a) today’s median income and today’s array of goods, services, and prices or (b) 1973’s median income (plus, say 25 percent) and 1973’s array of goods, services and prices. I think that so many people would reject the 1973 option that the stagnation hypothesis becomes untenable.

Even stranger: I learned this thought experiment over a decade ago from none other than Tyler Cowen himself! I think he called it the “deflationary century.” His point: Most of us would rather have $1000 nominal dollars to spend on year 2000 goods than $1000 nominal dollars to spend on year 1900 goods. Ergo: official statistics notwithstanding, the quality-adjusted price level has actually fallen over time. Years later he blogged it:

$5.00 back then goes a longer way, but I would rather earn $100,000 a year today, and yes that is not adjusting for inflation.

Of course, Tyler might say that his thought experiment works for 1900 versus 2000, but not 1973 versus 2010. But none too convincingly. Ultimately, though, I’m pretty sure he realizes that there’s been amazing progress over this period. But saying “slightly less amazing progress” isn’t as provocative as saying “stagnation.”

So here’s how I “defend Tyler” while at the same time attacking him: I would much rather have $1,000 to spend in 1973, or in 1900 for that matter, than today. I would use it to buy either 10 or 48 ounces of gold, which I could exchange for either $13,500 or $65,000 to spend on computers and sushi today.

If that is construed as cheating, I still would rather spend $1,000 on things from 1900. I could stock up on things that haven’t seen a big jump in quality. I don’t know exactly what; I’d have to go down to the Sears Roebuck or the general store and find out. But if nothing else, I could buy that cow and matching set of pigs I’ve always wanted.

I grant you that at some point, I would prefer having money to spend today. But if we cap it at $1,000? Heck yeah I would rather be able to buy stuff from 1900 than today. I can’t believe anybody says otherwise. Are you guys really taking the thought experiment seriously?

Last point: Like I said, I haven’t read Tyler’s book or even a synopsis. But if he’s claiming something mysterious happened in the US around 1973, that suddenly crippled its growth… Is he going to blame fiat money? My sources say no.

UPDATE: Duh I just thought of another one: Land! Think of how much prime real estate you could get with $100,000 in 1900.

I suppose they will say, “Bob c’mon, we’re talking about the CPI, so leave assets out of it.” So I don’t mean it as an investment. I’m saying, I think I would much rather have a $100,000 house built in 1900, than a $100,000 built today. So long as my neighbor has wifi and no password.

Calling Sumner’s Bluff on Stock Prices and Inflation Expectations

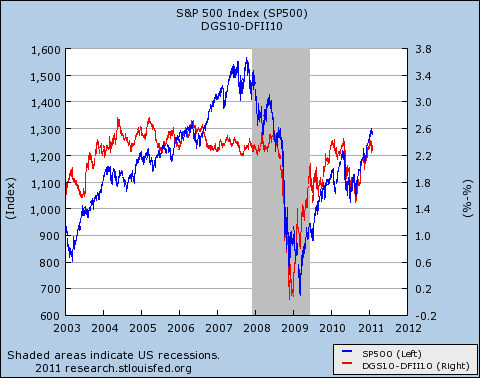

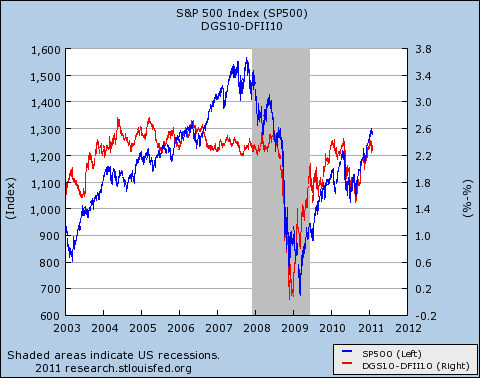

Yesterday I put up a lengthy post arguing that Scott Sumner and Paul Krugman were inexplicably claiming vindication from data that, if anything, I would have thought they would prefer to sweep under the rug. Specifically, since 2008 the stock market’s movements have been much more strongly correlated with the spread between nominal and TIPS yields on 10-year Treasuries (which is a common benchmark of “the market’s expected rate of price inflation”). In Scott’s words, this shows the market has been “rooting for inflation” ever since the Fed fell asleep at the wheel in 2008 and let NGDP growth falter.

I pointed out that I would have thought just the opposite result would have vindicated Scott’s quasi-monetarist framework. In particular, if inflation expectations (as gauged by the spread between regular and TIPS yields) had stayed flat while the stock market zoomed upward in 2009 in response to QE1, then it would have been harder for people like me to say, “That surge in stock prices in artificial; it’s just another bubble.” (Granted, I would have said that, and with no embarrassment. I think Greenspan fueled a stock bubble with much more modest pumping than Big Ben.)

But as it turns out, I don’t have any splainin to do after all. The chart above (which Krugman actually created) has provided me with a nice little illustration showing that increases in the S&P 500 since the crisis began, have been almost perfectly matched with changes in inflation expectations.

In the comments of my post, Scott begged to differ. Here is a portion of his reply:

Bob, Only 4 problems with your post:

1. You misread the graph. It doesn’t show that stocks move in proportion to prices, the scale are vastly different. Stocks move much much more [than] prices, even prices changes cumulated over 10 years.

2. My model does not predict that all of extra NGDP growth will go into RGDP, that’s what Keynesians sometimes claim (the more extreme versions of Keynesians.) I ALWAYS assume an upward sloping SRAS, although I argue it is relatively [flat] in deep recessions. but never completely flat….

First let me paraphrase what Scott is saying here, to make sure the reader understands the back-and-forth between us titans: Scott is saying that in the chart above, just because the red and blue lines move hand-in-glove from 2008 onward, that does NOT mean we can attribute every change in stock prices to a recalculation by investors of inflation rates over the next 10 years. On the contrary, Scott claims that the stock market is moving more than the corresponding shifts in inflation expectations would warrant, but we’re not seeing that on the chart, because the axes have different scales.

But (here’s Scott’s point 2) it’s crucial to note that the direction is always the same, for both series, since 2008. This is (apparently) great news for Scott’s model, because his model says that if Bernanke gets investors to expect, say, 10% more NGDP in ten years, then (say) 8% of it will show up as increased RGDP in 2021, while the other 2% will push up the price level in 2021. (I’m using round numbers; you can’t really add up the percentages like that.)

So investors will push up current stock prices because of both factors–they expect stronger “real” earnings in 2021 (relative to their expectations before Bernanke convinced them he was a real man) and they expect higher prices in general in 2021. (Note that the absolute dollar-price of various stocks will be higher in 2021 on account of both factors, which is why investors bid up current prices for those same stocks.)

So does everyone get Scott’s point? Even though Bernanke’s promise of 10% more NGDP leads to 8% higher real output, it also pushes up prices (and hence current inflation expectations). Thus, when we’re in a situation (as Scott claims) where the big constraint on the economy is insufficient NGDP growth, you will see stock prices and inflation expectations moving in lockstep. In contrast, we didn’t see such a tight fit before the crisis, because there were lots of other factors that were important, and stalled NGDP wasn’t binding.

It’s a beautiful story. As I predicted (and note it was a falsifiable prediction, proving I am a man of science), Scott was able to explain how that chart was his ace in the hole, with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed.

But as Columbo would say, I have just one more question: Should we take Scott’s word for it that the movement in stock prices is far greater than what could be attributed to a revision of inflation expectations? Since I had a bunch of pressing deadlines this morning at the office, I decided it was a perfect time to spend a half hour investigating Scott’s confident assertions.

First I checked the 10-year case. Just eyeballing the chart above, it looked like inflation expectations (over ten years) went from 0.2% to 2.4% from early 2009 to early 2011. During the same period, the S&P 500 went from 700 to 1300, an increase of 86%.

So the question is, could the jump in inflation expectations account for such a surge in stock prices?

The quick answer is “no.” If you had a stock worth $100 in 2009, and had it roll over at 0.2% for 10 years, it would be worth $$102.02 in 2019. In contrast, if that stock rolled over at 2.4%, it would be worth $126.77. So the change in expected average inflation rates could explain a 24% increase, but not an 86% one.

NOTE: Already this is awkward for Scott. Remember, he is saying that “the real problem is nominal.” So with unemployment above 9%, and people saying this is the worst slump since the Great Depression, it’s a bit weird to me that about 28% (=24%/86%) of The Ben Bernank’s stimulus gets soaked up by price inflation. In other words, that’s a pretty steep Short Run Aggregate Supply curve, eh?

NOTE #2: I also don’t think it’s right to say that investors just care about point estimates of inflation rates. For example, if The Bernank’s crazy policies since 2008 make investors think, “There is a 90% probability of 1% price inflation, a 9% probability of 4% inflation, and a 1% probability we go Zimbabwe,” you might see the stock and bond markets behave as the chart indicates. That is still more in the spirit of my worldview than Scott’s.

But back to the action: After seeing a victory (though admittedly slight) for Scott on a 10-year horizon, I thought, “Well why limit it to 10 years? After all, Scott thinks the market is so efficient that he literally doesn’t even believe in the possibility of bubbles. So what about doing the same analysis for 30-year bonds?”

Unfortunately, I don’t think FRED’s data on 30-year TIPS yields goes back far enough.

So then I tried 20-year bonds. And check this out:

First I figured out when the yields on 20-year Constant Maturity Treasuries bottomed out; it was 2.88% on December 30, 2008.

Then I looked up the 20-year TIPS yield on the same date: 2.20%.

Then I looked at the latest values (February 1, 2011 when I did the calculations) for both series: 4.37% for regular, and 1.81% for TIPS.

So the market’s 20-year average expected inflation rate (estimated using the method Scott and Krugman like) went from 0.68% to 2.56% during the period in question. Using the same approach of starting with a $100 stock and letting it roll over at the two rates for 20 years, you get an appreciation of 45% in equity prices that can be entirely attributed to the increased inflation expectations over 20 years.

Now the big question: How much did the actual S&P increase between December 30, 2008 and February 1, 2011? Well it went from 890.64 to 1307.59. That’s an increase of 47%.

So we see that Scott is still right on a 20-year time horizon: Changing inflation expectations can only account for 96% of the move in the S&P. That other 4% is property of the quasi-monetarists. Learn it, live it, love it.

Postscript

For what it’s worth, I really did accurately describe my approach above. In other words, I didn’t spend three hours searching through various bond series, and am now just reporting the one that worked. I checked the 10-year, saw it was promising, and then checked the 20, which I think Scott would have to agree is a better test of his worldview. Once I saw the result, I figured I could stop; my work was done here.

One other thing: I have checked the calculations, but hey I’m an Austrian economist and we’re not good with macro or math, so maybe I did something wrong, or maybe Scott will challenge the way I’m testing his assertion in the first place.

To be clear, I am not betting my worldview on the outcome of this calculation. Rather, I am pointing out that Scott’s claim of vindication doesn’t make any sense. It’s as if he took a Magic 8-Ball, asked it, “Does Bernanke need to print more money?” and then it said, “My sources say no.” Then Scott says, “A ha! I told you guys!”

In that context, I am merely saying, “Uh, if you’re gonna use that as your criterion, then you’re wrong. Not that I would have cared if it came out the other way.”

Are Sumner and Krugman Incorrectly Claiming Victory?

A friend who is a very sharp economist mentioned to me that when he reads my critiques of Sumner, it is very challenging to discern my argument. So if he was having trouble following my posts, I pity the fool with a normal IQ.

So for this post, I will start out at Square One. It’s appropriate to do so, because my ultimate point is going to be that–from what I can tell–Scott Sumner and Paul Krugman are taking what should be a stunning refutation of their position, and somehow turning it into a glorious confirmation. I am not accusing them of lying; I actually think that we’re so hip-deep into the arguments, that up becomes down.

So like I said, let’s start simple. Sumner (and Krugman but I’ll focus on Scott since I know his position better) believes that “money matters.” In other words, changes in the supply of, and demand for, money can lead to “real” changes. For example, if all of a sudden the quantity of money fell in half, it’s not the case that instantly all prices would go down 50% as well, leaving the “real” economy undisturbed. On the contrary, there would be a huge convulsion in the market, with lots of people getting thrown out of work, and the production of physical goods and services dropping sharply.

So far, so good. And to be clear, Austrian economists agree that monetary disturbances can affect the “real” economy; that’s the essence of the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle.

OK, so where does the disagreement begin? When it comes to our current recession, I say that the tremendous boom under Greenspan distorted the capital structure of the economy. We had painted ourselves into a corner, as it were, and output had to fall (relative to its height at the end of the boom) while workers and resources were shuffled around into more sustainable niches. When the crisis hit, the Fed and the government should have sat back and done nothing. (Or better yet, pegged the dollar to gold, cut spending, and cut marginal tax rates–I can dream.)

I admit there would have been an awful recession–the worst since the early 1980s at least–and a lot of investment banks would have gone down. But after 6 months or so, unemployment would have peaked, and a genuine recovery would have begun. By now, the awful Depression of 2007-08 would have been a bad memory. Unfortunately, the Fed and the government didn’t do what I would have recommended. Instead, they implemented the same strategies that their predecessors deployed in the face of the dot-com crash–times ten.

Sumner’s views are very much different. He says that the housing boom did indeed necessitate some “recalculation,” but that the reason for our disastrous economy since 2008 is that Bernanke hasn’t inflated enough. Specifically, the demand to hold money went way up, and Bernanke did not offset it with a corresponding increase in the quantity of money. The result is that nominal GDP (NGDP) fell. NGDP measures how much total spending occurs, and is the flip side of how much income people earn. So in the aggregate, people were earning less income in 2008 than they would have guessed the year before.

Sumner would admit that this “monetary shock” would be no big deal, so long as wages and other prices could adjust quickly. (In that scenario, people earn less money income than they expected, but no big deal because their money expenses are lower than they expected, etc.) Unfortunately, in the real world, prices and in particular wages are “sticky downward,” meaning they can’t go down as easily as they go up.

So as far as policy conclusions, Sumner and I are in complete disagreement: I think the Fed should stop pumping in more base money, and let interest rates rise as they may. (It’s a little harder for me to say if the Fed should start selling off its assets, or just let them mature without rolling them over, etc.) Sumner, on the other hand, would buy a round at the bar if Bernanke announced that he’d buy another $1 trillion in long-term Treasuries over the next 6 months.

Now instead of the more conventional open market operations, suppose instead that Bernanke decided to implement his infamous helicopter-drop scenario. In other words, Bernanke was literally going to print up $1 trillion in new Federal Reserve Notes, and then start randomly distributing them to US citizens. What would Sumner and I predict?

I grant you there are nuances on both sides, but I think to a first approximation–if we were on Family Feud and had to summarize our positions in 10 seconds before facing off–I think we would say something like this:

MURPHY: That’s a terrible idea! The problem with the economy is real, or structural. You don’t fix that by throwing green pieces of paper at the problem. Dumping more money into the economy won’t increase physical output, it will just make nominal prices go up. Monetary inflation won’t lead to real GDP, it will just lead to price inflation.

SUMNER: Murphy should stick to making YouTubes. The problem with the economy is nominal. It’s not structural, it’s monetary. Dumping more money into the economy will increase the output of physical things. The monetary injections will boost nominal GDP all right, but it will also boost real GDP. So we won’t see prices going up, as Murphy predicts.

Like I said, I’m obviously oversimplifying. But to a first approximation, I think the above is fair. In particular, Sumner (and Krugman) have been gloating over the fact that people like me wrongly predicted large consumer price inflation (at least measured by official CPI) when Bernanke started pumping in money. To restate the important conclusion: Sumner and I both agree that pumping in a trillion new dollars would raise NGDP. But I think it would (mostly) show up as increases in P, without raising RGDP (much). Sumner in contrast thinks it would (mostly) show up as an increase in RGDP, without raising P (much).

We’re almost to the finish line. Let’s take out nominal GDP and put in stock prices. Again, to a first approximation, the people like me who think the economy is stuck because of “real” issues right now, would think that pumping in a bunch of new money could very well raise the nominal level of stocks, but it would also raise expected price inflation.

In contrast, I would have thought Sumner’s position would logically entail that monetary pumping should lead to rising stock prices with stable (price) inflation expectations. This would match Sumner’s interpretation that the monetary pumping raised the prospects for future income growth, which would be “soaked up” by an expansion of real output. So nominal incomes would rise, but prices not nearly as much.

OK so assuming my rough characterizations of the “real” vs. “monetary” camp is right, let’s go to the tape and see which side has the data on its side:

The above chart shows the movement in the S&P 500 (blue line, index on left) against a common benchmark of “inflation expectations” (red line, gap between yields on 10-year regular Treasuries and TIPS on right).

As you can clearly see, ever since the crisis set in, movements in the stock market have matched perfectly with movements in expectations about the future price level. In other words, whenever the stock market has gone up, there has been a corresponding increase in expected price inflation over the next ten years.

I would have thought, to a first approximation, this would be a stunning victory for the “real” theorists. If, contrary to the above chart, the data had shown that the huge upswing in the stock market starting with QE1 in March 2009, went hand-in-hand with stable inflation expectations, then Sumner could have said, “Well now Murphy, what’s your story? If the market is booming just because of funny-money, and not because investors expect real economic growth, then why aren’t inflation expectations moving up too?”

(Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t have surrendered. I would have said, “Uh, it’s a bubble.”)

But I don’t have anything to be embarrassed about; the chart above is exactly what the “real” theorists would have hoped for, if they want to claim that the economy is stuck in a structural rut, and that throwing more money at it can only raise nominal figures.

PUNCHLINE: As the reader may have guessed, the reason I went through all this is that Sumner and Krugman claim that the above chart shows they’re right. Go figure.

And incidentally, one last thing: My real purpose in this post isn’t to say, “Ha ha, what fools. They don’t even know the implications of their own position.” On the contrary, my purpose is to show what a scam macroeconomics is. Sumner and Krugman no doubt can (and Sumner perhaps will, in response to me) tell a great story, with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed, about why the above chart proves they are right.

And yet, if the chart had looked the other way–say, if the behavior of the red and blue lines during 2006-2007 was shifted forward to 2009-2010–then it seems to me, they could have just as easily told a great story, with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed, about why that chart from an alternate universe proved that they were right.

Potpourri

Once again my Firefox browser is beginning to look like a ruler, so it’s time to clean house by blogging some of the many things I’ve noted over the past week or two…

* Lew Rockwell proves that he’s not always doom-and-gloom, by giving an optimistic interpretation to the events in Egypt.

* Jeff Tucker reviews Tom Woods’ new book Rollback (which I haven’t read yet).

* Speaking of Tom, he has started video blogging. He has a much nicer office and so I am at a disadvantage in my own home-made videos.

* An interesting video on “How Could a Voluntary Society Function”?

* So, does anyone else think it’s a big deal that Predator drones are now surveilling the US-Canada border? (HT2 LRC I think.) It’s not hyperbole when some of us say we are on the road to a full-blown police state. We really are.

* I take on Alan Blinder on a carbon tax. Blinder ironically relies on William Nordhaus’ simulations to make his case, when so do I!

* Wow some libertarian economists have been concentrating their fire on immigration restrictions lately. (No links handy, but I have in mind David R. Henderson and Bryan Caplan at EconLog.) I love this observation from Steve Landsburg:

The LA Times reports that Republican lawmakers have called on the Obama administration to return to the Bush-era practice of sending jackbooted thugs into private workplaces to arrest illegal aliens — revealing (as if we didn’t already know) that virulent xenophobia is alive and well in the Republican party. (Note well the hypocrisy of complaining that foreigners sneak into our country to take advantage of the welfare system, and then addressing the problem by focusing your deportation efforts on foreigners who have obviously come here to work).

* And now, your moment of Zen.

Do I Unfairly Pick on the Government?

Someone sent me the below email (reprinted with permission):

I am in the middle of chapter 3 Lessons for the Young Economist. So far I think it is a fantastic piece of work. The arguments are presented in a clear, unassailable manner that promotes true insight and understanding. I love the way it boils down to base principles and then bubbles up to useful insights and observations. I do have a suggestion for improvement, though: go easier on the ideological introduction. Working from “first principles” makes it very tough for opponents and skeptics to raise objections. If your principles about group actions are true, they should hold for corporations as well as governments. Spread around the examples.

e.g.

“After reading the lessons in this book, you will realize that there are perfectly sensible reasons for the actions of government officials. Their actions often don’t make any sense when compared to the official justifications given for the actions, but there’s a simple explanation for that too: government officials routinely lie. (Notice that lying is itself a purposeful action.)”

Replace ‘government’ with ‘corporate’ and the conclusions still hold. I think your piece would be more effective as a “wolf in sheep’s clothing” in this way. I use ‘wolf’ very tongue-in-cheek here, because I believe Austrian economics is the best explanation. It’s more like, positive meme injection. Put the medicine in a capsule that won’t be immediately rejected.

And it’s also just about intellectual honesty. Hold only principles sacred. Don’t pick winners.

I totally understand what he is saying, but I must confess that it doesn’t sound nearly as compelling to me to say, “Corporate officials routinely lie” as to say “Government officials routinely lie.”

Don’t get me wrong, I understand that on any given day, there are corporate officials who are lying to the public. But by the same token, on any given day there are dentists and high school principals who are lying to the public. So when we say “such-and-such routinely lie” I think it implies something stronger, that it is part of their job description as it were.

What do you guys think? Is this just showing my bias as a corporate shill (or as an anti-government zealot)?

It’s Official! Next Week Murphy Will Debate…

…Jerry Dwyer, an economist with the Atlanta Fed.

I am going to be one-half of the lunchtime presentation at the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) meeting in Atlanta on Thursday February 10th. They have graciously made an option for people who just want to go to the lunch and watch the debate.

Be careful when you go to the link; it looks like it’s saying the date is February 7, but that’s just their cut-off for ticket sales. Also note that if you do sign up for this, you need to print out your payment confirmation to get in the door the day of the event.

According to this preliminary flyer, the lunch seminar goes from noon – 1:30pm (Eastern time). I assume that is still accurate but you may want to double check for yourself. (I’m driving out there the night before so I can afford to have rational ignorance on this matter.)

I am going to say that the Fed is making markets more unstable with its current policies, and of course relate it to my views on the housing bubble.

Dwyer is going to offer the rationale behind the Fed’s current policies.

Lessons for the Young Economist in HTML

Wow this seems like it would have been a lot of work. Thanks Nielsio!

Twin Spin: Debt Ceiling and Sticky Wages

I forgot to blog last week’s “current events” article on Congress and the debt ceiling.

Then today, I respond to Karl Smith’s invocation of “sticky wages” as a justification for monetary and fiscal activism. Note that this is not my response to the quasi-monetarists (though it’s applicable); this particular article has been in the queue for weeks. An excerpt:

[W]e should note that “sticky wages” are not a market failure at all, but a quite appropriate response to the worker and employer’s desire for predictability. In other words, it is not some arbitrary fluke that allows copper and gold prices to adjust by the second, while labor contracts tend to be for periods of a year or more.

Suppose things were the opposite, and that workers’ wage rates could adjust every minute according to supply and demand. Someone making $20 per hour today, might make only $8 per hour tomorrow. In such an environment, workers would build up an enormous cushion of savings, because they would have to draw down their liquid assets to get them through periods of below-average wages. Very few workers would buy houses, but would instead rent apartments, ideally on month-to-month terms.

I have no doubt that if this were the norm, interventionists of various stripes would invent sophisticated mainstream models showing that such an outcome was “Pareto inefficient.” If only the government would pass laws, requiring labor contracts to lock in wages for longer periods, then the enhanced predictability would increase the welfare of everyone in society.

Because they could count on their paychecks for a longer horizon, workers would reduce their antisocial “hoarding” of cash. Without such benevolent government intervention, the perfectly flexible wages of the cutthroat capitalist economy would be yet another example of market failure.

When I wrote the above, I intended it as a hypothetical (yet crushing) argument. But in retrospect, I think I have heard interventionists complain that “piece wages” are unfair, the government should get involved, blah blah blah. I’m not saying that they’re the same interventionists, but still, it’s ironic that whether workers get paid a fixed hourly wage for (say) a year, or whether they get paid in direct proportion to the spot market value of their output, either way it’s evidence of market failure and justifies government intervention.

Recent Comments