Murphy Inflation Smackdown

[UPDATE below.]

Brad DeLong unleashes hell on me at his blog for my (price) inflation bet with David R. Henderson. Especially in light of my Les Mis post yesterday, I had thought about either ignoring this or just linking to it in a Potpourri with no comment. However, at the risk of seeming petty, I think there really is a major issue here that none of the Austrians have brought up (in the comments of my Facebook post, for example, when I linked to DeLong with only the wisealeck comment that I have never before been attacked with so many adverbs). So here are my quick reactions:

==> I screwed up. I obviously wish I had never made that bet with David, since (a) it looks like I’ll be out $500 and (b) what is worse, my error gives ammunition to people like DeLong who want to challenge my policy conclusions and Austrian economics more generally.

==> DeLong accompanies his post with a chart of year/year percentage changes in core CPI. Well, that’s stacking the deck. The bet was about headline CPI, which almost hit 4%. Nowhere near what I needed, of course, but much better than DeLong’s chart would indicate.

==> The comments section is funny. You would think amidst everyone’s psychoanalysis of me, they could acknowledge my presence. I think they ignored me though because that makes it harder to speculate on what an idiot and a liar I am. (I’m being serious, that comment section is odd right now.)

==> Speaking of the above, to the extent that my preferences matter to you guys, please don’t bash the heck out of DeLong in the comments here. Makes it harder to play the victim card.

==> Finally my substantive point: I have never seen any of these guys explain why price inflation (and interest rates) are the decisive criteria for whose model and hence policy recommendations are right. Consider, for example, the infamous Christina Romer unemployment graph, showing what would happen with and without the Obama stimulus package. As far as I know, DeLong didn’t ask Romer to announce to the world that she had been wrong about everything and to spend years at the feet of Joe Salerno. No, Daniel Kuehn for example thought that anyone who wanted to use the Romer forecast as a test of the efficacy of her model was putting out “complete horsesh*t.”

So I’m not saying the following–like I said, I screwed up in a way that is relevant for economists talking to the general public. But since the following is exactly analogous to how Keynesians deal with the unfortunate Romer situation, I’m curious why they think Austrians who warned of large price inflation can’t say the following:

Hey, it’s true, we threw out some predictions of how much prices would rise, and we were off. But our basic model wasn’t wrong, it was just the underlying forecast of the baseline. Bernanke really did create a bunch of price inflation, it’s just that in the absence of Fed action, the drop would have been bigger than we expected, so on net we didn’t see as large of an increase in absolute terms. Indeed, Krugman et al. agree with the economic model involved: they all congratulate Bernanke for having staved off massive price deflation. So what’s the argument here? We’re arguing about the counterfactual of price movements in the absence of Fed monetary inflation.

Seriously, how is the above any different from how Keynesians defended Christina Romer, to the point of saying anybody who thought her prediction should be used against her was intellectually dishonest?

UPDATE: In case someone is tempted to say, “Oh sure Bob, Romer screwed up the unemployment forecast, but Krugman and some other Keynesians nailed it, showing that the Keynesian model is OK…” Fine, I’ll point to Mish, a super-free-market guy (not sure if he formally embraces Austrian economics per se) who has been calling for deflation since the crisis set in. So why doesn’t the example of Mish (and there are others) rescue free-market critiques of Big Government?

For that matter, David R. Henderson isn’t a Keynesian, and he was the one who took the other side of the bet. (Bryan Caplan even went further and gave me a longer time frame.) David and Bryan don’t call themselves Austrians, but they’re not Keynesians either. Doesn’t anyone see how absurd this is? It would be like pointing to Krugman’s critique of the stimulus as being inadequate, and saying it proves our recession is a supply-side problem.

The Bishop’s Grace Makes Les Mis Possible

I watched the new Les Mis and loved it. Hugh Jackman was surprisingly good: Near the end I actually thought they might have been dubbing it, because I thought he sounded so much like the Broadway soundtrack. (I didn’t think that in the beginning of the movie; I need to watch it again to see if I just adjusted or what.) Russell Crowe was the only one who really made me wonder what his agent was thinking, but I actually think more highly of him for being willing to sing like that in front of the world. I don’t mean he was awful, I’m just saying, he sounded like a schoolgirl and I’m surprised he was willing to do that.

Anyway, I was struck (yet again–I have seen this in several formats many times since childhood) by how crucial the bishop is to the whole story. To set the scene: Valjean is paroled after doing 19 years of hard labor for stealing bread for his starving niece. He can’t get any work because of his prison record. A kind bishop takes him in, giving him a warm meal and place to stay for the night. In the night Valjean steals the silver and takes off, but is hauled back by the police. Here’s what happens (go to 3:15):

Once Valjean is on the receiving end of such mercy and grace, he becomes a fountain of it in his own life, eventually doing something that is far nobler than what the bishop did.

In your own life, you may often feel that you’re a sucker for turning the other cheek and being classy or kind or whatever word is appropriate. But remember that you might inspire that one person out of 100 who will learn from your example and amplify it tenfold. Then someone will see his example, and so forth. Just as we can’t fully anticipate the full ramifications of our sins, so too we can’t comprehend just how helpful our mercy and compassion will be.

Take a chance.

Sometimes You Should Look Up the Numbers, Fiscal “Cliff” Edition

I’m working on an op ed on the “fiscal cliff” and just for kicks, I decided to see just how savage these massive cuts in spending would be. Now let me confess, the results shocked even me, so by all means, somebody show me what I’m overlooking…

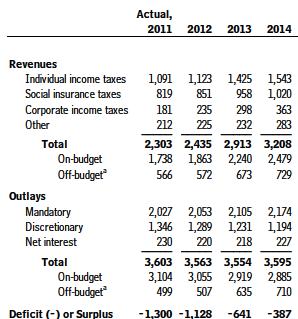

Here’s a snapshot from a table in the CBO’s August 2012 forecast:

We are already in Fiscal Year 2013; it started on October 1. So the column for 2012 is already done; the changes (if no deal is reached) will show up in the 2013 numbers.

So: If nothing is done and we go over the “cliff,” then total spending will drop from $3.563 trillion to $3.554 trillion, a reduction of $9 billion, or 0.3%. Notice everyone, I am saying a drop of three-tenths of one percent. Then, by 2014, total spending will have risen to above where it was this year, in 2012 (because 3,595 > 3,563).

On the revenue side, going over the “cliff” is projected to raise receipts from $2.435 trillion in 2012 to $2.913 trillion in 2013, an increase of $478 billion, or 19.6%.

The deficit in 2013 is projected to be $641 billion, down from the actual $1.128 trillion deficit in 2012, for a drop of $487 billion.

In summary, if we go over the “cliff,” the government plans on sharply reducing the budget deficit compared to its 2012 level. Of this $487 billion reduction in the federal budget deficit, the savings will come through two mechanisms:

==> A cut of $9 billion in government spending (1.8% of the deficit reduction), and

==> An increase of $478 billion in tax receipts (98.2% of the deficit reduction).

Happy holidays!

Clarification on Fed Monetizing Deficit in 2013

I realized something wasn’t adding up with the numbers, and went and double-checked the JP Morgan report that led me (in this video) to say that the Fed may monetize the entire federal budget deficit in 2013.

Well, that’s a misleading way to describe it (which is why I’m posting this clarification). What the JP Morgan report (and Zero Hedge blogger) are saying is that in its latest announcement, the Fed pledges to continue buying $40 billion of agency-issued mortgage-backed securities per month, but will also start buying on net $45 billion of Treasuries. (Before, with “Operation Twist,” the Fed was buying $45 billion of long-term Treasuries but was simultaneously selling off the same amount in short-term Treasuries. Now it’s going to engage in net purchases.)

So what the JP Morgan report was saying, is that $85 billion per month x 12 months = $1.02 trillion for the year in the growth of the Fed’s balance sheet, and that’s just about what the federal budget deficit is projected to be. Hence, in their words, “QE will offset almost all of next year’s government deficit.”

But the problem with saying it this way, is that the word “offset” makes you think it’s a euphemism for “monetize” when it’s arguably not. For example, suppose the Fed planned on buying $1 trillion of real estate in Hong Kong. Would we still say “QE will offset almost all of next year’s government deficit”?

Now it’s true, the MBS that the Fed is buying, is ultimately backed by the US taxpayer through Fannie Mae et al. So in a sense, those MBS are federal government obligations, just like Treasuries.

Yet in another sense, they’re not “just like Treasuries.” If the borrowers faithfully make their mortgage payments, then the US taxpayer doesn’t kick in a dime. Another problem is that even if you count MBS as equivalent to Treasuries, then “next year’s government deficit” would have to include not just the net increase in Treasuries held by the public (and Fed), but you’d also have to include the net increase in outstanding agency-issued MBS.

So, unless someone corrects me yet again in the comments here, I’m going to stop saying the Fed plans on monetizing the entire deficit next year, since I don’t think that’s really accurate.

As Usual, Sumner Ignores Micro

In this post Scott Sumner shows he would make a great talent agent:

Back in 2009 I argued that only elite monetary economists should sit on the FOMC. Some of its current members are not even monetary economists, elite or otherwise. They are unqualified people serving in the most important economic policy position on the planet. I also argued that we should do whatever it takes to attract the best:

I don’t care how much is costs, even if we have to pay FOMC members a billion dollars a year, we will save much more money in the long run if we can get “strong” central bankers (pun intended) who have the vision to see what needs to be done, and who understand that effective policies require explicit target paths for macro aggregates.

Three years later Matt O’Brien made an even better case:

That’s another way of asking how long it will take the economy to return to trend. Here’s where things get really depressing. According to Fed Vice Chair Janet Yellen, we won’t get back to full employment until after 2018. If we assume the output gap will steadily shrink until then, that leaves us with roughly another $4 trillion in lost income. Maybe more. If Svensson really could double our recovery speed, he’d be worth $2 trillion to us. Even if that’s being wildly optimistic, something on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars probably isn’t. Tell me that wouldn’t be worth paying Svensson a billion dollars a year. Maybe more.

A trillion dollars . . . a billion dollars . . . and now the Financial Times is quibbling over a lousy million dollars:

Mark Carney took some persuading to become the next governor of the Bank of England. We know that he initially resisted George Osborne’s blandishments, only agreeing to apply when the term of the appointment was reduced from eight years to five.

But the full price paid by the chancellor has only this week emerged with news that on top of the £624,000 in salary and pension contributions Mr Carney negotiated for himself, the next governor will also receive a housing allowance worth £250,000 a year. This number was computed, we are told, on the basis that it would, after tax, give Mr Carney enough money to rent a house for his family in one of London’s smarter neighbourhoods. It also makes him, when all the cash amounts are totted up, among the best-paid central bankers in the world.

Scott focuses on macro but misses the marginal analysis. This is basic stuff. Yes, we can stipulate that Mark Carney’s move to the BoE will make the world many trillions of dollars richer. But that doesn’t mean we should pay him that much. I would be willing to say, “Keep printing money until the economy ain’t broke no more!!” for a mere £300,000 a year, and a monthly visit to dine with the Queen. I’d hate to see how much Scott thinks we should pay garbage men or teachers.

Potpourri

==> Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Seeing how much it has bolstered my career, Greg Mankiw and Gene Callahan both try to catch Keynesian bloggers in self-righteous contradictions. I actually don’t think Mankiw’s point works very well, since Krugman clearly refers to “recovery” in his recent post whereas in 2003 the US wasn’t in recession. (Anyway, look at the catfight he started with DeLong.) Gene’s gotcha was pretty good, though.

==> A Time article (I think? the URL has “swamp” in it?) that mentions the Austrians, if derisively. So we’re at least past the “First they ignore you” phase.

==> Jeff Tucker looks back on the Laissez-Faire Club, one year into it.

==> John Cochrane is angry, or cynical, or something. Anyway, he’s sarcastic about the Fed, so I like it.

==> Joseph Stiglitz sounds a lot like Sheldon Richman in this article, saying the Fed’s actions are helping the fat cats but hurting the average saver. Joe, duck! Sumner’s gunning for your head!

==> I can understand libertarians who oppose both gun control and the Drug War. I can understand right-wing conservatives who oppose gun control but support the Drug War. I can understand left-wing hippies who support gun control but oppose the Drug War, because they don’t really see the connection. But I never thought I’d read an economist who supported gun control in the same article that he opposes the Drug War.

==> I posted this article on Facebook and all hell broke loose.

==> If you’re bored, look at David R. Henderson busting Crooked Timber on a ridiculously misleading post. (David wasn’t as harsh in his commentary as I am being.)

==> I am starting to think that Gene is right, that having discussions about evolution is pointless. In the comments of this post, I had to stop banging my head against a brick wall for fear it would reduce my changes of reproduction. (Believe it or not, I don’t even agree with Gene’s conclusion on this particular argument! But his critics didn’t seem to have the faintest idea of the modest point I was trying to make. I am starting to doubt they possess consciousness.)

A Ghost From Landsburg Past

It looks like Steve Landsburg and I will have this disagreement as an annual tradition now. He re-posted his thoughts on Ebenezer Scrooge, which include this line of argument:

In this whole world, there is nobody more generous than the miser—the man who could deplete the world’s resources but chooses not to. The only difference between miserliness and philanthropy is that the philanthropist serves a favored few while the miser spreads his largess far and wide.

If you build a house and refuse to buy a house, the rest of the world is one house richer. If you earn a dollar and refuse to spend a dollar, the rest of the world is one dollar richer—because you produced a dollar’s worth of goods and didn’t consume them.

Who exactly gets those goods? That depends on how you save. Put a dollar in the bank and you’ll bid down the interest rate by just enough so someone somewhere can afford an extra dollar’s worth of vacation or home improvement. Put a dollar in your mattress and (by effectively reducing the money supply) you’ll drive down prices by just enough so someone somewhere can have an extra dollar’s worth of coffee with his dinner. Scrooge, no doubt a canny investor, lent his money at interest. His less conventional namesake Scrooge McDuck filled a vault with dollar bills to roll around in. No matter. Ebenezer Scrooge lowered interest rates. Scrooge McDuck lowered prices. Each Scrooge enriched his neighbors as much as any Lord Mayor who invited the town in for a Christmas meal.

Saving is philanthropy…

Of course I understand the point Steve is trying to make here, but this train of thought just doesn’t sit right with me. A major difference between saving and philanthropy is that with the former you can undo your “generosity” once you consume. So for Steve’s accounting to work, a saver is being altruistic, while a consumer is being greedy.

There’s a certain logic to that, but it seems contrived to me. Consider the following scenarios:

(A) Jim earns $100 at his job. He uses the money to buy a steak dinner ($100) today for himself.

(B) Jim earns $100 at his job. He uses the money to buy two pasta dinners ($50 each) today for a date and himself.

(C) Jim earns $100 at his job. He uses the money to buy a ticket to the Superbowl, which won’t occur until next year.

(D) Jim earns $100 at his job. He uses the money to buy a ticket entitling him to two steak dinners (for him and a date) but it won’t become active until next year.

(E) Jim earns $100 at his job. He buys a one-year bond at 100% interest and then a year later, uses the $200 to two steak dinners for himself and a date.

How does altruism/selfishness play out in the above scenarios? (Oops! This is confusing, I just realized. Don’t worry about him and the date being selfish or altruistic; I mean, is Jim being altruistic toward the rest of the world, versus Jim spending money on his own narrow interests.) For example, would Landsburg say Jim is more altruistic for 12 months in (C) compared to (A), at which point the selfishness kicks in? I would rather say there is the same level of selfishness in both transactions the whole time; in either case, Jim is using his income to buy the consumption good he prefers. It just so happens that the flow of services from the Superbowl ticket doesn’t start for a year. Why is buying future consumption morally different from buying present consumption?

Recent Comments