A Note on Stock Market Volatility

So if I promise to criticize myself, can I get a blogging gig at EconLog?

I understand the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, and I think it’s a very good way to take a first crack at the markets. The thing that annoys me about many EMH proponents is that they think they are being empirical and scientific, when they often are clearly able to explain any outcome in their framework. Steady growth? Just what EMH predicts. Massive crash? Just what EMH predicts. In practice, the EMH is non-falsifiable, which is ironically the criticism many of its proponents level at others.

I think this following passage from Scott is a tad slippery:

Murphy seems to suggest that the fact that Austrian economists were not surprised by the volatility is a point in their favor. But why? Who was surprised? If you had asked me a year ago “Do you expect occasional volatility, up and down?” I would have said yes, and also that I had no idea when that volatility would occur, or in which direction the market would move.

Look, there was nonstop coverage of this on NPR when it happened. They were trotting out all kinds of people, including Austen Goolsbee, to make sure Americans kept their money in Wall Street. I’m not making this up, give me a break.

Monday showed the biggest intraday point swing in history. (Granted, you would want to look at percentage swing for a better comparison, but I can’t find such a ranking.)

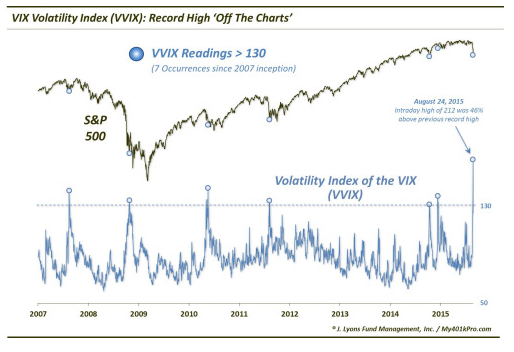

And according to this guy’s analysis, by one measure of market volatility–the VVIX–Monday blew the previous record out of the water:

If you want to say I’m a broken clock, or that we should wait and see what things look like in three years, etc., that’s fine. But come on, don’t act like predicting “more of the same” two weeks ago is consistent with what just happened.

What’s your explanation for the crash, Bob?

I’m still failing to see what the actual prediction was. Are you (RPM) saying that this unprecedented tumble in the markets was due to the funny money Fed business? What then if Fed balance sheet expansion was still taking place? Would the market volatility of late had been postponed?

Sumner made a strong point,

“One other point. If the sharp decline early in the week told us something deep and meaningful about the wisdom of ABCT, then does the recent rebound weaken that argument, or was that rebound also consistent with the model.”

Assuming the rebound has strength and momentum, how does RPM explain this despite normalizing monetary policy?

If this unprecedented market drop is quickly erased, then what is the value in the predictions and warnings from Austrians?

🙂

Normalizing monetary policy?

The rebound seemed to happen right after this:

“Fed’s Dudley: Case for September Rate Increase Now ‘Less Compelling’”

http://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-dudley-says-new-york-economy-is-a-bright-spot-1440597601

That might be a good point. Shucks.

🙂

Serious question for EMH proponents who use it to attack Austrians.

If the government passed a law called the General Market Price Regulation, whereby by law the government would dictate all prices of actual goods, but set them according to the market prediction of the market clearing price, why would this not be an improvement over letting markets determine prices?

I’m being serious here, it seems to me like EMH proponents have, perhaps inadvertently, dismissed the Knowledge Problem and rescued Market Socialism. Why do none of them ever say so?

(I want to stress that, I know my answer to that question, but I know my answer can’t be their answer because my answer defangs the EMH critique of Austrian Business Cycle Theory.)

How do you intend to set up a futures market where people can make predictions of something that is government controlled? Ummm, let’s just ignore the fact that we do this already with the Fed and interest rates.

You seem to be saying that if I can lift my left foot up in the air, and I can also lift my right foot up in the air; then should be very easy to lift both up at the same time and fly away. Or is that exactly the point you are trying to make?

With regard to the first question, I said market predictions of the market clearing price, not the future price itself.

With regard to the point I’m trying to make, Efficient Market Socialism doesn’t work because markets don’t already know the market clearing price, the actors in the market have to discover it.

So I’m making a bet on a future “market clearing” price, how do I know whether I collect on the bet or not?

If there’s a surplus ie an excess of unsold goods:

if I bet that the market clearing price was lower than the market thought it would be and thus where the government set the price, I win the bet. If I bet that the price the market thought was correct was too high or just right, I lose.

Similar thing if there’s a shortage.

Basically you bet on whether setting a particular price will lead to excessively accumulated inventories, or to bread lines.

Oh gosh, this is like jumping into the LK rabbit hole and deja vu all over again.

Who gets to decide what constitutes a surplus of unsold goods ? Who gets to decide what makes a shortage ?

The people making bets on this would be inclined to a certain point of view, the government regulators are well, government. What’s the precise definition of “market clearing” in a world where prices are fixed? I put it to you that there isn’t one.

Valid questions, Tel, but not relevant to the point I was making.

You’re arguing that this market socialist scheme couldn’t work, and I agree. But you’re arguing it can’t work for reasons that are different from the arguments Mises and Hayek raised.

“Who gets to decide what constitutes a surplus of unsold goods ? Who gets to decide what makes a shortage ?”

I’ve actually been trying to hammer this issue home, as of late, because I think it’s so foundational.

All production processes end with consumer goods, all right?

The whole point of production is to supply a consumer at the end of a process.

If there isn’t sufficient consumer demand to buy the goods that are produced, then all the higher-order production processes will not be sufficiently financed so as to be profitable.

This is Menger’s Theory of Imputation I can’t shut up about.

The answer to your question is “the consumer”.

The producer is, in a sense, a slave to the consumer, in that his profitability depends on their demand.

If you don’t produce what consumers want, then you shouldn’t expect your business to be profitable.

Goods are in a surplus when consumers don’t want them at the price they are being sold at.

Goods are in a shortage when consumers want more of them than are being supplied at their current price.

Since people eventually tire of losing profit, neither surplusses or shortages are sustainable without price controls.

The surplus goods will have to be sold for less if the producer wishes to make any money at all on them.

And the shortage of goods could be alieviated by a higher price to incentivize their production (read: price gouging).

If the government passed a law called the General Market Price Regulation, whereby by law the government would dictate all prices of actual goods, but set them according to the market prediction of the market clearing price, why would this not be an improvement over letting markets determine prices?

I’m not sure I understand the difference between prices being set based on the market’s prediction and prices being set by the market. Perhaps you can explain?

Josiah, it could be very different, if one assumes market actors who know the market clearing price have reasons for not setting prices at that level.

If one assumes market actors already know the market clearing price.

Maybe a concrete example would be helpful.

Menu costs: even if I know where my price should be I don’t change it because the expected gain is less than the cost of changing all my signs and labels.

Sorry, I mean an example of how a concrete price would get determined under your idea vs right now.

For example, how would the price of a can of coke get determined?

The government announces a price ahead of time and a market exists for futures contracts in what the correct ie market clearing price would be. these futures contracts are bets on the *outcome* of a given price policy. “Pay to A if government sets price at x or above and there’s a surplus” ie if Coca Cola reports greater than desired inventories. The government announces it’s future prices periodically based on the current market forecast of the market clearing price. If the market is generally consistently betting the government’s announced price for Tuesday of next week is too high, the Government lowers its announced price, and the reverse if it’s too low.

I’m not an expert in setting up prediction markets but I don’t see why, *if you assume people in the market already know what prices should be*, that this couldn’t be made to work.

That sounds like a bizarrely complicated system that at best would be a lot worse than just using markets.

It sounds like the issue is you think the EMH implies that people know ahead of time what prices should be, which of course isn’t true. Even the super-strong version of the EMH only says that prices incorporate currently knowable information, rather than all information.

“EMH only says that prices incorporate currently knowable information”

And that’s precisely why EMH cannot refute Austrian Business Cycle Theory.

And that’s precisely why EMH cannot refute Austrian Business Cycle Theory.

A lot of people seem to think they can use ABCT to prove we’re in a bubble. Hard to square that with the EMH.

Josiah you can’t change the definition of EMH mid argument from “Even the super-strong version of the EMH only says that prices incorporate currently knowable information, rather than all information” to “bubbles are logically impossible” but thank you for letting me catch you doing it.

“A lot of people seem to think they can use ABCT to prove we’re in a bubble.”

It helps to say that bubbles are higher-order investments that consumer demand hasn’t made profitable.

If I know that consumers don’t want some item at a particular price, and I can only supply that item if I charge more, then I won’t engage in production of that good.

But if money-printing lowers the interest rate such that I can, in nominal terms, profitably charge less, but at the same time the supply of materials hasn’t changed, I will use my artificial purchasing power to compete with other producers for materials that were otherwise sustainably priced (according to consumer demand relative to supply).

My additional, fraudulent, purchasing power puts upward pressure on prices, removing real resources and raises their marginal utility, unnecessarily.

Remember that abundance of resources – which is a good thing – is what lowers marginal utility; There’s more of a good, and so I can use the next additional one for a less urgent end.

That’s *why* uncoerced prices go higher and lower – because of the marginal utility to the individual.

If you distort the representation of marginal utility by printing money, you’re destroying information that people need in order to know their costs in terms of goods and services.

Andrew,

Bubbles are logically possible. What’s not logically possible is for to be the case both 1) that people know bubbles exist, and 2) the super strong EMH is correct.

For there to be a bubble, prices have to be overvalued.

If you can know we’re in a bubble, then that’s knowable information.

If the super strong EMH is true, then all knowable information is incorporated in prices.

Which means the fact prices were overvalued would be incorporated into prices.

Which means they wouldn’t be overvalued.

Do you follow?

Yeah, but that’s totally wrong. Knowing some prices are “overvalued” is not the same thing as knowing which or how much. EMH treats “it’s a bubble” as sufficient information to destroy any bubble. The fact that so many people deny there’s a bubble is just icing on the cake for why that can’t work.

Scott Sumner said ‘My general view is that most types of recession are almost unforecastable, and that the least bad prediction is always “more of the same.” ‘. Which seems a reasonable position and actually is consistent with reality over the past 5 years.

Austrians seem just as bad at predicting the details of recession/market crashes as everyone else, but when they do occur they (and the Post-Keynesians) will immediately claim they vindicate their set of beliefs, but then when (as in the mini-crash in 2011) the markets quickly recover they never acknowledge they were wrong. There is also a perception (I am sure unfair) that while others may be stressing about seeing their savings fall in value, Austrians are busy hoping for the worst.

I think Bob’s posts on the topic this week and his post on the 2011 mini-crash ( that Scott’s extract from in his post), both exemplify why people get annoyed with the Austrian approach to these periodic market corrections.

Transformer-I feel like at this point reiterating the points I’ve made already would be pointless. Here’s what I’ll try:

You’re construing Austrians as claiming their theory would make them effective central planners and then you’re complaining that they deny such a thing is possible. Do I really need to explain where your thinking us going wrong?

@Andrew_FL

“You’re construing Austrians as claiming their theory would make them effective central planners and then you’re complaining that they deny such a thing is possible”

Not really. My beef is that even is a perfectly free market there may still be some “irrational exuberance” and the need for occasional market corrections. And it just seems like lazy analysis for Austrians to say “look ABCT in action” every time one occurs without identifying actual evidence of mal-investments etc that would back up these claims

Is your view that the volatility we’ve seen recently is just a normal market correction?

If by “normal” you mean “relatively minor” then it certainly would not surprise me if the markets have recovered and reached new highs within 2 years.

(To hedge my bets: If things worsen in China and the worlds CB makes bad calls then this could drive a global recession and it could take much longer for the markets to get back to previous highs).

So your view is it’s a market correction that could end up becoming a global recession depending on China and the reaction of central banks, right?

Why do you believe there is so much volatility?

Also, what kind of actions do think central banks will need to undertake in order to prevent a global recession if China continues to falter?

I think we have volatility because of economic uncertainty

I think we have economic uncertainty becasue of political meddling in economies and bad CB policy.

I think optimal CB policy would be to dissolve themselves and let the money supply be left to market forces.

I agree with Austrians on a lot of things. Just not on “market corrections prove ABCT is true” thing.

I don’t think any Austrian believes market corrections prove ABCT. Austrians are saying that these huge swings in volatility are not surprising to us. We believe that what the Fed and the State have done is continually replace one bubble with another and in the process keep digging the eventual hole that much deeper.

So when we see volatilty spiking like this, and you have a bunch of people scrambling around trying to understand the reason, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that Austrians are going to say this is what we expect to happen based on our theory.

It doesn’t mean we are saying that the next depression is upon us. Maybe this will be the catalyst and maybe it won’t. But we do believe that the Fed and the State have set us up for a bigger fall than we saw when the housing bubble burst. Just as we believed that the response to the tech bubble set us up for a bigger crash.

Transformer, would you have felt better if, in this post, I had acknowledged that some might object I am a broken clock, or that we can’t really know the big picture until, say, 3 years out?

No, I would still have found these examples of “stock market correction = validation of Austrian (or PK model ) is true” annoying.

Despite appearances to the contrary I am annoyed too.

But with respect to your response to me above: complaining that Austrians don’t identify the malinvestments in real time is exactly what I mean when I say you complain Austrians refuse to play central planner.

New rule on this post:

Nobody is allowed to say “I think Sumner makes a lot of sense” unless you specifically clarify whether you also mean his description of what just happened as “occasional volatility, up and down” and his further statement that nobody was surprised by what happened on Monday.

You can say, “Yeah Bob, Scott’s statements are fine, nobody was surprised by that occasional volatility.” I’m not doing a litmus test.

All I want to be sure of, is that when you start defending Scott and criticizing me, are you referring to the actual content of this post, or are you talking about some other disagreement he and I have.

I’d argue that EMH is a subset of Darwinian evolution, and runs into the same problems of being a non-falsifiable tautology. With EMH the markets are the only acceptable measure of how well the markets are performing. With evolution, the fittest are whatever happens to survive. In both cases, the answer is absolutely true, but also pretty much useless from a practical point of view.

Mind you, saying “God wanted it to happen” is also non-falsifiable, but without the circularity. After all, there isn’t much that could possibly happen and then afterwards you say, “Ah ha! God couldn’t possibly have wanted THAT to happen.”

I don’t follow your evolution argument. Survival of the fittest is a tautology, since those that survive are defined as the fittest. That this is the driver of evolution is not a tautology, and could be disproved if it were false.

All we would need to see is future generations favoring the less fit. Bacteria that do not survive as well in an antibiotic media becoming the dominant variety for example. We would then have disproved evolution by natural selection.

Failure of inherited characteristics would also falsify evolution. If a rabbit were to give birth to a reptile, for example. Or if physical characteristics were identified having no relationship to genetic makeup.

So who gets to decide that those future generations are less fit? I mean they are less fit that what exactly?

So if I find one example of a petri dish where the antibiotic has killed the bacteria entirely that would completely disprove evolution, right?

Fitness is success in reproduction, but it correlates with survival to a point. So if you see the variety that had less success reproducing being favored in subsequent generations it would be evidence against evolution. If you find a population of bacteria in a petri dish that totally failed to reproduce and were entirely killed, yet they are the most succesful next generation, that would disprove evolution.

It’s interesting to note that Progressives considered “undesirables” to be successful at reproduction due to their willingness to accept a lower standard of living (than the Progressives were trying to create for themselves).

They didn’t have to work [for the Progressives] as hard, so they were burdened with the Minimum Wage to put them in their place.

So you are saying that the only thing that could disprove evolution would be if the dead came back to life? Seems like that’s a contradiction in terms… which once again just proves that evolution is a tautology.

No empirical experiment can ever create a logical falsehood, because logic lives outside the material world. Thus, if logical falsehood is the ONLY thing that could ever disprove your theory then your theory is a mathematical tautology.

I did not say thay was the only way to disprove evolution, but that it was a way.

That would merely indicate we needed to reconsider our views on how inheritance works. It would not disprove evolution, because regardless of whether rabbit gives birth to a reptile, or the other way round, in any situation what you are left with becomes (by definition) the fittest.

In other words the concept of evolution has no predictive power of itself. You may happen to know something about typical variations amongst rabbit breeds, but that is knowledge specific to rabbits, and some other species (such as bacteria) can produce a completely different result. Evolution (and EMT) are supposed to be theories that are invariant of the breed (or the stock) in question.

You cannot use evolution to predict what you will be left with in another 100 years, any more than you can use EMT to decide the likely price of any particular stock. What happens is what happens… that’s the core of the theory.

Evolution is understood to work by passing on inherited characteristics. Darwin did not understand the mechanism of inheritance, we think we now understand it much better. If charateristics are not inherited the way we think they are, then our theory of evolution is in tatters.

No, you can equally have evolution operating in a technological space where designs and patents are copied in a totally different process, but regardless of that over time the most useful techniques get used and the less useful techniques don’t get used. But that’s in effect the same tautology.

Also in the business space, a successful business keeps going and stays in business, while the unsuccessful business goes into liquidation, and the resources from the unsuccessful business get sold off and used for other purposes. That’s the core of any free market… but also a tautology given that only the market can determine which business is successful. At least in the business space they have a concept of profit and loss, but even that isn’t a reliable indicator because you have not-for-profits some of which get used a lot, and hang around (e.g. Netscape/Firefox browser).

Business designs do get copied, but one particular corporation does not need to worry about reproduction, because it can life forever if needs be.

Then you can also have evolution of “memes” which do get copied, by yet another totally different mechanism.

So to sum up, no the biological mechanism of inheritance might be of interest to biologists, but the details of that are irrelevant to evolution as a theory.

“In other words the concept of evolution has no predictive power of itself.”

Not specifically, you need to know the selection pressures also. The law of gravity has no predictive powers by itself, you need to know where the masses are.

With gravity, you need to know the present state (mass, velocity, etc) and you can use the theory to predict future states (if no other forces are imposed).

With evolution (in any context) knowing the initial state does not help, only by actually watching it happen can you discover those “selection pressures”. You are just finding more intricate ways to hide the circularity of it. The “selection pressures” are not measurable from the initial state, they are only only measurable once you know the final state. That’s the whole problem, time goes forwards, so a theory that makes predictions must be able to work entirely from initial conditions… you aren’t allowed to look ahead in any way whatsoever. Just-so stories on a retrospective basis don’t cut it.

Not true at all. if you know present state and selection presures you can confidently predict future trends. Bacteria plus antibiotic = resistant bacteria for example.

“EMH is non-falsifiable”

I basically agree with your take on this recent action in the markets, Bob, so I respectfully disagree with this statement. It’s not quite true. All three versions, or strengths, of the EMH have falsifiable propositions. Is EMH overused? Probably. But it does say we can’t predict the future, and that if the market is efficient, all currently available public information should be reflected in the stock price. And there are phenomena that violate market efficiency, like post-earnings announcement drift. Finally, market efficiency is often described in a binary way – either markets are efficient or they are not. It’s actually a spectrum, like sunlight shining through a filter. The more information can be built in to prices, the less dense the filter is and the more sunshine gets through.

By the way, for anyone who doesn’t know, this is where the real business cycle (RBC) thinking on market crashes comes from: new information about future productivity comes in that wasn’t previously known, and it’s bad news. So the market processes that new information quickly, you get a big adjustment and you move on. An inefficient market processes it slowly and you get downward drift that is predictable. I think one can nest RBC within ABCT, by the way. Might be a paper there.

I don’t read Sumner, so I’m not defending him. I did want to offer clarifying comments on the EMH, though. It is probably the most tested hypothesis in finance. One final note though, to circle back to the start. Bob’s statement has some truth to it. The EMH is non-falsifiable because you need to specify a model that generates asset prices. So every empirical test is a joint test: that EMH is true, and that your model is true. If your test fails, you don’t know which hypothesis was falsified. This is known as the Roll critique.

Finally, EMH can be thought of as the result of good policy towards financial markets. Anything that improves transparency and facilitates trading and openness will foster market efficiency. Any kind of interference with markets reduces efficiency. ABCT is interesting here because it explicitly states that the money creation monopolist sends false signals to the market. I haven’t worked through the implications for market efficiency, but to my thinking bad information builds up the error term around market prices, pushing them farther away from “true” values which would lead to less efficient markets.

For anyone interested, I have a bit more to say here: https://crankyprofj.liberty.me/dont-ever-say-bubble/

Jeff,

Nice comment above and nice article by you that you linked to. I think there’s a word or two missing in the last sentence in the second paragraph of your article.

David,

Thanks for reading both comment & article. I seem to always need a professional copy editor, though, and thank you catching that.

You’re welcome, Jeff. I would have said it in a comment on your site, but to do so, I needed to register with liberty.me and didn’t want to do so.

“It’s what the asset would sell for if everyone had the same information and agreed about its implications.”

In other words the “Finance Definition” is an explicit rejection of subjective value theory.

I had high hopes based on your comment here, Jeff, but your blog post just disappointed me.

I followed your link but I cannot find anything that shows how EMH is falsifiable.

The very acceptance that bubbles are undetectable (and beyond that, they are undefinable in empirical terms) must also imply that EMH cannot be falsified. If you could measure the bubble (possibly even after the fact), by detecting it you would therefore be demonstrating the market is not efficient. However, if the bubble is not even in principle measurable at all, then nothing you ever do can confirm either it’s presence or absence… that’s very bad in empirical terms because you then have no measurements at all!

My article wasn’t about EMH, it was about bubbles and how the term is basically nonsense.

EMH is falsifiable because it makes falsifiable predictions. For example, weak-form EMH says you can’t use historical information to earn abnormally high returns. Abnormal is relative to the risk taken. So a falsifiable hypothesis to test weak-form would be using technical analysis rules that extract information from past price data. Most research shows this is not a reliable form of generating abnormally high returns.

Semi-strong form says that prices impound all publicly available information. So I can’t use 10-Ks to beat the market. This implies that value investing isn’t a reliable method of earning abnormal returns. The example I gave in my original comment of post-earnings announcement drift is an example of evidence against market efficiency. In a very efficient market, we shouldn’t see any drift – all the information impounded in the earnings announcement should cause the price to move up or down (or not at all if there are no surprises) once, and then back to a random walk.

Strong form of course means even insider information is impounded in the price. No one believes this form describes reality, because insider trading is verboten.

I’m a big fan of deadpan humor, I bet that one works well when you have a crowd of people who are very quiet and you can catch one or two start to snicker.

It does bring up a point though, given that selling drugs is against the law, most drug dealers don’t provide too much information about their operations, and yet they seem to have customers and profits somehow. I would guess it’s much the same with insider trades, people don’t go around wearing a bright red t-shirt “I’m an insider trader”… so it’s up to the authorities to detect them, but reliably detecting them would require knowledge of that intrinsic value which we don’t know, we only know the market value. Some of them do something stupid and own up to it (remember Rene Rivkin).

Thus the same principle which says you cannot stare at a market price and point out the presence or non-presence of bubbles, is also going to say you cannot stare at a market price and point out the presence or non-presence of insider trades.

OK, that requires that you have some extra piece of information, not just the market price, and you also have a theory about how this extra piece of information should affect the market price. As you already said, you need a model, and you are testing your model. Market prices moving around ahead of the earnings announcement might well be evidence of insider trading, or perhaps a good bit of guesswork, or could be someone who researched the company in other ways (maybe hung around the store to see if they were busy).

Indeed, Zerohedge generally can point out prices moving ahead of any major announcement, you get stories like that every few weeks… but almost never does anyone do anything about it. Wake me up when Yellen gets busted over leaking internal deliberations into the financial industry… we know that’s never going to happen, she’s more politically protected than Hillary.

There’s another problem with these empirical EMH tests — suppose some guy is very good at using technical analysis (and nothing else) to turn a decent profit… that guy is hardly going to advertise the fact and explain it to everyone. Just like the drug dealer or the insider trader, the strong incentive is to stay quiet about it. I don’t believe you can even detect that guy in operation (legally) without some additional way of observing his internal process. Maybe he goes for a decade and then retires, or finally publishes a book about his amazing technical methodology… well once the book is published then it’s useless. Even after the book is published, you can’t be certain whether he really explained what he did, or even maybe he was picking up on some sentiment from news articles and not realizing this affected his trading strategy, or just an everyday liar.

I’d say it might be empirical if the researcher has a godlike power to scrutinize all the market participants and check exactly what they are up to (e.g. in a computer simulation you could do that) but real world researchers have no special powers.

I’m not sure what you are trying to say here, but aren’t rumors information?

Well everything is information, but what I’m doing is responding to your specific point:

Thing is, if someone was out there sitting in a basement for 10 years doing exactly what you claim is impossible, then by your own argument about bubbles, you would have no mechanism to be able to detect that guy — doubly so when the incentives would be to avoid detection.

So what you have said is, that there’s this phenomenon called “X” and you make the falsifiable prediction that “X” never happens therefore when you don’t find it, that proves your theory… but you also (indirectly) demonstrate that “X” is unmeasurable. Can you see the difficulty in that experimental setup?

This exact problem also applies to the authorities attempting to enforce insider trading laws, and with minimal amount of searching you can find a lot of circumstantial evidence suggesting that insider trading does go on, but trying to nail down a specific instance and certainty of detection is basically impossible. Where there have been convictions is only when people have given themselves away in other ways, blabbing about it, or being turned in by someone they trusted (i.e. information OUTSIDE the main channel of the market trading).

Jeff, your understanding of EMH needs work. The semi strong form of the theory does not only imply that you can’t use value investing to reliably beat the market. It also implies that you can use any public information based strategies to reliably beat the market. And yet there are individuals who have reliably beaten the market. But the semi strong form of EMH treats these events as pure luck and chance precisely because the semi strong form of the theory by definition forbids a skills and talent based reliable beating of the market.

For the strong form, again what you take from the literal definition of it is not right. The claim that nobody believes it because insider trading is “verboten” is a sloppy generalization. Some people really do believe the strong form. It is why the strong form is a theory in the first place, and why Leprechaun magic is not.

Moreover, the fact that insider trading is illegal does not necessarily imply that capital prices are not affected by insider trading. It could still take place.

Sorry, Major Freedom, but you’re not understanding what I’m saying. Semi-strong form efficiency means you cannot use public information to beat the market. This is the accepted definition by finance academics. Strong form means all information – public and private. Again, that’s the definition set down in academic finance. Talk to Eugene Fama is you don’t agree. My comment about insider trading being forbidden was tongue-in-cheek in a sense, but it also means markets can’t ever be fully efficient in this sense.

Here are two theories about the stock market:

1) stock prices follow a random walk, so it’s impossible to say in advance whether it will go up or down tomorrow.

2) the stock market is DOOMED; if it goes down tomorrow, that’s more evidence that it’s DOOMED; if it goes up tomorrow, that’s evidence that it is even more DOOMED, as the crash when it comes will be even bigger.

Both theories are about equally able to explain whatever happens to the stock market tomorrow. But that doesn’t make them equally good as theories.

If 2 is supposed to be ABCT, you’ve missed the mark.

I know snark is you schtick, but try to at least approximate the actual theories you don’t like in your criticisms.

Two things:

1. Taking the S&P500 Since 1960 or so, there have been about 100 days with price changes as large or larger than the one we experienced on Monday – so it happens, say, twice a year. Rare, but not unprecedented.

2. The VVIX that you reference is not a good measure of stock market volatility – it is instead a measure of the volatility of the volatility of the market. The VIX is a better measure of market volatility (implied from the options market again), and this measure shows that Monday was a volatile event, but not historically unprecedented – roughly on par with the events in summer of 2011, but still, even if we use the VVIX, there have been 7 such readings (as your post shows) since 2007, so again, maybe a once per year thing.

Consequently, I would say there is validity to the opinion that there was nothing particularly special about the market volatility we’ve experienced over the past week or so, but I won’t comment on whether or not it was surprising. I think the definition of a drawdown like that shows that some people were surprised.

The actual propositions of the three primary types of EMH are falsifiable. The way EMH is used in the blogosphere isn’t.

EMH is just another example of blackboard theory. It might be, as you say, a good first approximation but it utterly fails to account for the fact that prices can be distorted and not corrected for a period of time. It relies on a silly Panglossian worldview of markets.

ABCT takes the form of an if-them statement. The only way to find evidence against it is for the “if” to happen and the “then” to not happen. It doesn’t attempt to time the market.

I think that implies that ABCT is only useful in explaining how a boom-bust cycle will play out, and that can really only be done ex-post. It helps us understand the causal factors. If that isn’t useful, fine, but don’t treat it like theories that do have explicitly testable components.

That said, I think you were premature in declaring victory on this one, Bob.

Well said Levi. While I have been pushing back hard on commenters ridiculing Austrian theory, I also think there’s a good chance Bob is calling this one prematurely.

What exactly do you think he is calling prematurely?

The end of the current unsustainable boom.

I must’ve missed that. I’ll have to go reread his article.

Alright, I just read his article again, and I’m not seeing where he said this was the end of the bubble. I see him saying the fragile economy and volatility isn’t surprising to Austrians. I see him briefly explain the ABCT. I see him saying that the actions by the Fed and the State have set us up for another inevitable crash. But I don’t see him making the much stronger claim that the bubble has burst.

Dan-It’s the impression I got about what Bob was trying to imply, less than that he explicitly said it.

But fair enough, not everyone is going to read it the way I did.

I should have phrased that better, Dan.

I think Bob should be more careful about saying “ABCT explains this” without laying out precisely how it explains said condition. I don’t know if that would have staved off Henderson’s misguided question, though.

I thought that was what he was doing with his brief description of ABCT.

I took that article as saying “Hey, average Joe, you know how the talking heads on the news are scrambling every time these wild swings happen? Well, maybe you should check out the Austrian school that has been warning all the “solutions” applied by the Fed and the State are actually sowing the seeds for more misery down the line. Here is a brief explanation why we feel this way.”

Your cult is in rebellion, Bobby. Too many of us lost money on your ridiculous hyperinflation predictions. You’d be better off becoming a full time creationist; you have more credibility as an evolution-denier than an economist.

I went way into debt and bought into the Sydney real estate dip back around 2009, after watching that market for a long time. My theory (based on what a lot of Austrians were saying) was that governments faced with a crisis will surely print money, drive down interest rates and protect the housing bubble at all costs. Sure enough that’s exactly what they did and I’d probably double my money if I sold today. It’s been bad for the country, but good for me, I even asked them not to do it several times in public to prove I’m not selfish, but they did it anyway, like I knew they would.

The same Austrian theory says that at some point the Sydney market will crash just like various US markets have done. Steve Keen (not an Austrian, but really into Minsky and debt-deflation) says this once every few months, and sooner or later he’s going to be right. Wish me luck for selling at the right time. Then again, based on current rental prices in the area, if all I do is rent it out I can get back an annual return of about 6% of what I paid in the first place (ignoring any further capital gains) which is also pretty good as far as I’m concerned.

Your lack of properly understanding EMH surely comes from your educational background. You are an Economist not a Quant.

Argh, okay so here is the problem. Predictions are a problem.

However based on what I can understand the real difference between What Bob is saying and What Sumner is saying, and I hope both of you forgive me if I am wrong might be best summed up in the following analogy.

Pretend there is a kid who is playing in the street.

Austrians look at this and say, ‘Hey if you play in the street you are eventually going to get hit by a car that does not see you.’

Sumner and others say, ‘You will get hit, of course, but if we give you enough padding you can play in the street as much as you want, not take too much damage, and there is always a hospital in which you can mend at and be as good as before.’

The Austrian says, ‘Only cross the street when you have to’

This does not mean that you have ‘predictive’ powers above and beyond seeing the obvious that if you do X eventually Y will occur. There is also a difference in encouraging people to play on the train tracks ( they may choose to if you do not suggest it ) and telling people to have fun in a different way.

The problem is that everyone ‘KNOWS’ a bubble and volatility will occur. If you have ever played a Game of Jenga you can continue to increase the height of the wooden block but eventually it is going to fall down. Austrians say, just produce new blocks and build it up, it would appear that the Fed says, well lets take from the middle and everywhere we can to keep it propped up as best as possible and fill in the holes with the new stuff.

It is a question of stability. Yes there is still going to be a cycle, yes there is going to be irrational exuberance ( you cannot keep some kids from playing on railroad tracks ) but the severity of the damage and the ability to recover SHOULD be better in one than the other.

Not only that but one favors those that play on the tracks while the other treats everyone equally. At least that is my take on it.

Again this is imperfect and I would love to be better schooled in this regard. Feel free to correct or reject my thoughts here.

“It is a question of stability. Yes there is still going to be a cycle, yes there is going to be irrational exuberance …”

The Austrian position is that there will not be a cycle / irrational exuberance (of a systemic nature) without prior misallocations of resources caused by price distortions.

Price distortions, of a systemic nature, can only happen through attempts at central planning. A free market cannot result in systemic bubbles because the costs to the investor of misallocating his own resources (which would happen anyway) are more readily apparent.

Printing money hides the price signals which would allow investors to better see malinvestments. It does so by distributing the costs on a vast number of unsuspecting holders of the currency that’s being inflated.

I think it really helps to understand what is meant by “price signals”; that voluntarily priced goods tell you something about the sustainability, or lack thereof, of consumer demand, and therefore the profitability of higher-order production processes.

This video was really helpful on the topic of “price signals” (though I don’t remember Salerno using that particular phrase):

The Birth of the Austrian School | Joseph T. Salerno

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZRZKX5zAD4

It’s more than a question of stability, it’s a question of planning.

All human enterprise requires that someone makes a plan, and is willing to push ahead with that plan while adapting to ongoing uncertainty. Small levels of uncertainty can easily be accommodated, but massive uncertainty reduces the capability of people to achieve anything.

In theory, markets (especially futures markets) should help the planner because she can buy suitable hedges, thus improving the certainty of her enterprise. This is like buying insurance for your car or something. Problem is if the market as a whole collapses and there’s nothing tangible backing those insurance contracts, you get bankruptcy and wide scale liquidation, then you are back to uncertainty again (until it clears up and blows over).

Out of curiosity, how does the ABCT predict high intraday stock market volatility?

Page Q in Human Action explains.

I see the EMH as Hayek’s argument about dispersed knowledge applied to financial markets. I don’t think it’s at all incompatible with ABCT and that Austrians should like it even though Menger or Mises didn’t come up with it. It’s compatible with ABCT because the collapse of the ABCT bubble is completely unpredictable as far as timing and qualifies as new information which asset prices have to adjust to. If it were so easy to make money off the ABCT, then Austrians would utterly dominate the world having accumated so much wealth through the financial markets. I say this as a giant fan of the theory and not a detractor. I simply don’t think it offers the crystal ball that some do and I would favor a market based prediction over that of any economist for the same reason that markets allocate resources better than central planners.

John, with respect, I think you’ve got this totally backwards.

The version of EMH that proponents use to attack Austrian Business Cycle Theory is nearly perfectly diametrically opposed to Hayek’s entire argument against socialist calculation. In that version of the theory it’s an easy, trivial task for the market to find the right prices, the information is just “out there” and gets priced into markets as soon as anyone realizes it-which is virtually instantly. There is essentially no role for the entrepreneur, the idea of individuals acting in the context of markets discovering the right prices is completely eliminated.

I don’t hate this version of the EMH because Mises didn’t think of it. I hate it because it’s antithetical to thinking clearly about how markets actually work. In fact, it’s a thought terminating cliche.

To me the bottom line on bubble theories is that they don’t make money. You’d probably make more money believing the EMH. I never recall Mises or Rothbard talking about bubbles; only malinvestment. They also did not tie their theory to financial markets or say that it was useful to participants in a financial market. To make those claims as someone like Schiff has done seems to be overstepping the bounds of the theory.

“To me the bottom line on bubble theories is that they don’t make money. You’d probably make more money believing the EMH.”

OK, but then don’t blame “greedy capitalists” for just trying to make money in the distorted economy.

Yes, their actions could not help but build up the bubble, but they don’t know that prices have been distorted by artificial credit expansion.

It’s true that they are cronies, being given government privileges that result in so-called “overinvestment” (really just malinvestments), but such cronyism is unavoidable under those distorted conditions, and if you want to make money in that environment, then you’d better be a crony.

Did I say a single thing about greedy capitalists? You incorrectly put that in quotes and what you said was completely unrelated to what I said. You sir are an idiot.

You did not say a single thing about greedy capitalists.

My point was to defend against your claim that the “bottom line” on bubble theories is whether or not they can make you money.

The implication is that Austrian Economics is useless.

But, here we are – the libertarians among us, anyway – advocating for the freedom to make as much money as you want, but then free markets get the blame when the admiral pursuit of profit results in massive losses of wealth for some.

I just wanted to caution you that to make money (in paper terms) while adopting a business strategy that ignores bubble theories is to engage in the very malinvestments that result in economic crashes.

It irks me that people believe Austrian Economics to be impractical, is all.

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2015-08-28/nassim-talebs-fund-made-1-billion-monday-how-other-hedge-funds-did

Well Nassim Taleb just clocked up a billion dollars (he probably only gets to take home a small fraction because his backers will want their share). That may not fit your definition of making money but speaking strictly for myself it’s enough to get kind of interesting.

This is slightly off topic (not entirely), posted at the bottom because of size. I’ve been reading a bit on Nassim Taleb. So I’m a bit of a fan of Eric Falkenstein and I’m aware that those two have some sort of grudge feud going, but I never took much interest in how it got started. Not surprising when they are kind of similar guys doing kind of similar work, there’s no doubt a bit of professional rivalry, but anyhow they are both into statistical measures of market behaviour, and investment strategies that basically consist of a special type of technical analysis of historic data (not exactly the standard “off the shelf” technical analysis, there’s a lot more statistics involved, but doing something original is the way to win).

Nassim Taleb just popped up in the news as winning a $1 billion bet on the VIX and the recent market volatility upset. Good luck to him, he’s involved in hedge fund management, so I guess it’s his job to win bets like that. From his own point of view obviously he just beat the market. From my point of view of course, Nassim Taleb IS the market (or part of it) so if I want to beat the market now I’m up against that guy PLUS all the other market participants. That’s one of the conceptual problems for EMH, because in a competitive situation, viewpoint is really important. There is no objective participant.

Getting back to some of my favourite topics, there’s an article that discusses “The Precautionary Principle” in the context of genetically modified organisms (GMO’s) and Taleb’s fat tail vs thin tail statistical analysis. I’m delighted to see he also has an analysis of biological evolution here as well — not a general purpose analysis, but specific to the subject comparing natural selection as against human-controlled selective breeding as against humans in the lab directly modifying the DNA.

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B8nhAlfIk3QIbGFzOXF5UUN3N2c/edit?pli=1

So the point here is to distinguish things that are “natural” from things that are “unnatural” and make the claim that a Precautionary Principle applies to the GMOs but not to other situations. So the problem with this concept is that every new generation is unique, there’s never going to be another Bob Murphy, each generation is similar to their parents but different. This is true of GMOs as well, they have similarities to what they were made out of (the DNA is copied) but they are different in as much as the DNA has been jiggered around with.

In order to claim that one process is “natural” and the other “unnatural”, or at any rate in order to make a claim that one such process is more dangerous, we would need a yardstick to measure how much is the correct amount (or some reasonable bounds) that a subsequent generation should differ from the previous generations. Taleb does not propose any way to build such a yardstick, but even if he did we would need to then discover some key threshold that crosses the boundary of what can lead to a catastrophic outcome… we have absolutely no idea where this threshold might be, and there’s nothing in evolutionary theory that could tell us.

This is my problem with the whole deal, evolution is a tautology, and a fairly trivial one at that. There’s no way to argue it is wrong, because a tautology is never wrong, but at the same time, using it as a tool does not provide the key information that you would need to isolate a dangerous genetic modification from a safe one.

By the way, personally I reject the use of the Precautionary Principle as any sort of principle at all… it’s just Pascal’s Wager applied to different theoretical (and unmeasurable) potentially disastrous outcomes. You cannot apply statistical probability theory to the end of the world (or the beginning of the world) because these events don’t offer any meaningful sample size. Equally, you cannot apply probability theory to your own death and the afterlife.

Come to think of it, there should be a Reverse Precautionary Principle (RPP) which states that if anyone can think of any massively beneficial outcome of a project, then the project should ALWAYS be attempted, regardless of the small probability of success. That’s also Pascal’s Wager.