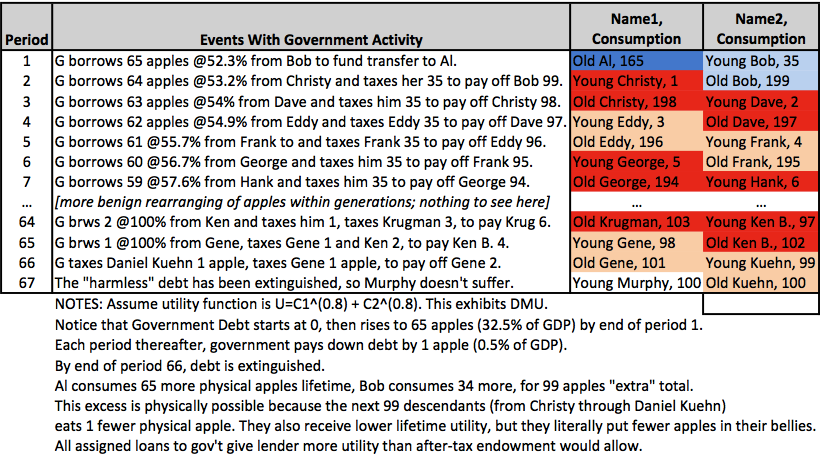

Illustration: Today’s Generation Eating More at Expense of Next 65 Descendants

[UPDATE below.]

OK kids get a cup of coffee and study this thing:

I spent a decent amount of time making sure the above works. I confess I didn’t actually fill in the whole table; I just did the beginning, then skipped to the end and worked backwards. But I’m pretty sure I could fill in the middle part with appropriate taxation of everybody, to get it to all work out and be internally consistent.

Assuming I don’t have any mistakes in the above, are any of you going to tell me with a straight face that Krugman’s readers understood that the above outcome is possible, when he kept telling them (paraphrasing), “The present generation can’t impose burdens on future generations by running deficits today. Sure, they can cause redistribution within a given future generation among people who are living simultaneously. But that’s not at all what people mean when they say that today we can make future generations poorer collectively, the way debt can make a family poorer in the future.”

UPDATE: OK I definitely made at least one mistake in my original version of this; there are only 65 descendants who get hurt by this scheme. This makes sense, because the government debt was original 65 apples, and it is paid down one apple per year.

However, I’m having trouble reconciling that with the brute physical fact that Al and Bob clearly eat 99 more physical apples lifetime than they otherwise would. Since the total number of apples isn’t changed, and since we have each new descendant (up to and including Daniel Kuehn) eating one fewer physical apple lifetime, shouldn’t that imply there are 99 such descendants getting dinged?

I have already spent way too much time on this today. If you guys can help me see what bonehead mistake I’m making, that would be great…

Get with the programme Bob, all the cool kids are using interactive debt tables nowadays.

Wow that’s cool. I can almost forgive you for stealing from my grandkids.

But Bob, Old Al consumed more at the expense of Young Bob. Period! You transfered from 65 apples from Bob to Al. Then Al died. The debt had nothing to do with it, except as the vehicle of the transfer (which could as easily have been taxes)! Nothing “flowed back” from latter generations to Old Al!

Gene, again, we all understand how this physically works. Answer my question: Do you think Krugman’s readers knew that “you can’t harm future generations collectively, you can only redistribute within future generations” was consistent with the above type of outcome?

And you don’t think someone warning about “we can’t eat more apples today and pass down an apple-debt to our next 65 descendants” could be forgiven for such a statement, looking at the above plan?

Old Al consumed more at the expense of Young Bob. Period! You transfered from 65 apples from Bob to Al. Then Al died. The debt had nothing to do with it, except as the vehicle of the transfer

Doesn’t Bob come out ahead in this scenario? He gets 234 apples instead of 200. Whereas if the transfer had been achieved via taxes, he would have only gotten 135 apples. The people who lose out from the transfer aren’t around in period 1, so you certainly can’t replicate the transfer by taxing them in period 1.

“Doesn’t Bob come out ahead in this scenario? He gets 234 apples instead of 200. Whereas if the transfer had been achieved via taxes, he would have only gotten 135 apples.”

No blackadder, you just tax young Christy 99 apples in the next period and transfer them to Bob.

No blackadder, you just tax young Christy 99 apples in the next period and transfer them to Bob.

You can’t do that in period 1, since Christy is not around. The best you could do would be to promise to keep the transfers in period 2. If period 2 comes around and the government decides not to raise taxes, Bob is out of luck.

Right, but Christy’s lifetime overlaps beneficiary Bob’s. Absent inheritnace you can only gain from the other guy alive when you are alive. This is part of what PK and Lerner meant. And it can be done with taxes not debt. (So the fact of debt imposes no additional burden.) Gene put it well on his blog:

Absent inheritnace you can only gain from the other guy alive when you are alive. This is part of what PK and Lerner meant.

Are you excluding Dean Baker because you think he threw in the towel unnecessarily? Notice how in his last word on the subject, he admitted Nick had found a counterexample to Baker’s original claims, and so Baker switched to an empirical argument?

At the time I chided Baker for not being more forthcoming about his earlier mistake, but compared to you and Callahan, he was the equivalent of Paul of Tarsus. (Again, I am not as mad at Krugman as you guys, because I think Krugman honestly doesn’t see this type of possibility yet. I think he skimmed Nick’s examples involving only 3 periods, and didn’t realize the possibilities.)

At no point have I addressed what Baker said or thought.

What you showed is one guy, with govt contrivance, screwing a youngster. Eating Gene’s kid’s desert as it were. And then did it sequentially. That is not thios gneration eating the desert of kids who will be born 50 generations hence. It is Bob screwing Christy in line with what PK said was possible. And then that process begun afresh and renewed. And so on.

Bob, you’re showing that a debt transfer *can* occur. Dean is making an estimate about how much it *is occurring*.

Neither of these says is must *ever* occur which is what Nick has been implying.

The crux of the difference in opinions is on the bondholders. Whether making them pay for their own bonds constitutes “a transfer” to “the past.”

I think this is an illusion, but Nick doesn’t.

Anon wrote:

Bob, you’re showing that a debt transfer *can* occur. Dean is making an estimate about how much it *is occurring*.

Neither of these says is must *ever* occur which is what Nick has been implying.

No, this is totally wrong, except for the part about Dean (Baker). He was saying it couldn’t occur, up through Friday October 12, but then he realized he had been wrong and then switched to an estimate of its importance by Saturday October 13. Nick has, throughout, been saying it could occur.

No, this is totally wrong, except for the part about Dean (Baker). He was saying it couldn’t occur, up through Friday October 12, but then he realized he had been wrong and then switched to an estimate of its importance by Saturday October 13. Nick has, throughout, been saying it could occur.

Bob, I don’t think you understood my comment.

Nick has been saying it can occur, but that under certain situations (r greater than g) that it *must* occur.

Dean Baker has admitted that it *could* occur and is estimating how much it is occurring right now.

Nobody has shown that it must occur *even when r is greater than g* only that it could.

Nick, gets around this by ignoring that bondholders can be (and are) taxed to pay for their own interest payments. (Or possibly by ignoring that bondholders bought their bonds by choice.)

(Also, tax (or spending policy) in the period they bought their bonds, can be such that bondholders consumption will be the same (in the present), but not more than (in the future) *had they not bought the bonds*. (For example, in Krugman’s Santorum example: the people “getting” bonds can consume the same as they would have without the bonds whether or not the government taxes the younger generation to pay off the bonds or defaults.)

In the entire table above, no real goods and services travelled back in time.

Well, duh. It’s not like Bob or Nick have been arguing that debt burdens our children by using aorist rods. There’s no literal time travel involved. The argument is that you can use debt financing to achieve a similar result.

Well, duh. It’s not like Bob or Nick have been arguing that debt burdens our children by using aorist rods. There’s no literal time travel involved. The argument is that you can use debt financing to achieve a similar result.

Thank you Blackadder, for helping me stay sane. This is really amazing.

(1) Krugman relies on some true propositions to reach a very misleading conclusion.

(2) Bob shows that those same propositions are consistent with an outcome that all reasonable people (so we exclude Gene and Ken B.) would agree would shock Krugman and his readers.

(3) Gene and Ken B. continually point out that the demonstration in (2) relied on the same propositions as Krugman in (1), and hence is in total agreement with him.

MF or Blackadder, you guys are good with analogies. Care to come up with one for the situation? I’m tapped.

No Blackadder. The claim by Bob et al really is that you can have a problem with debt that you *cannot* cause with transfers. Because if you can replicate it with transfers amongst the living then there is no direct impoversihment of the future there is only redistribution.

PK likened the ‘debt burden’ to a Santorum transfer tax. If a transfer can replicate the effect then the problem is ditribution not impoverishment of the future.

Ken B. wrote:

No Blackadder. The claim by Bob et al really is that you can have a problem with debt that you *cannot* cause with transfers.

No it’s not.

“(so we exclude Gene and Ken B.) ”

Don’t forget to exclude Krugman and Landsburg.

Sigh Deep nesting again. But Bob is denying this, from PK:

“Suppose that … President Santorum passes a constitutional amendment requiring that from now on, each American whose name begins with the letters A through K will receive $5,000 a year from the federal government, with the money to be raised through extra taxes. Does this make America as a whole poorer?

The obvious answer is not, at least not in any direct sense. We’re just making a transfer from one group (the L through Zs) to another; total income isn’t changed. Now, you could argue that there are indirect costs because raising taxes distorts incentives. But that’s a very different story.

OK, you can see what’s coming: a debt inherited from the past is, in effect, simply a rule requiring that one group of people — the people who didn’t inherit bonds from their parents — make a transfer to another group, the people who did. It has distributional effects, but it does not in any direct sense make the country poorer.”

So he is arguing debt has effects transfers don’t.

MF or Blackadder, you guys are good with analogies. Care to come up with one for the situation? I’m tapped.

Here’s an analogy:

Statist man says the true proposition that people are capable of acting badly. Statist man then reaches a misleading conclusion that implies we need a monopoly on force (state).

Bob points out that the same proposition of people capable of acting badly is also consistent with no government, that reasonable people would accept (e.g. if people are capable of acting badly, then a monopoly on force would be an attractive legal method for people who like to act badly, to act badly with impunity, thus establishing a permanent institution of bad action).

Callahan and Ken B continually point out that because Bob agrees with statist man’s true proposition, Bob must therefore agree with what statist man concluded. They also insist that Bob is just playing word games with the word “government”, because a bunch of private security agencies would be considered by statist man as still a government, and hence Bob agrees with statist man in the double sense, and he doesn’t even know it, so it’s up to Callahan and Ken B to make him see the light.

Ken B:

But Bob is denying this, from PK:

For Pete’s sake, nobody is denying that there is no change to cross sectional wealth at the national level!

The OLG model is showing that current INDIVIDUALS alive today can, via debt, increase their lifetime consumption at the expense of future INDIVIDUALS not yet alive today, provided some assumptions hold (no perpetual rolling over of debt, no Ricardian Equivalence, etc).

For the life of me I cannot understand why you refuse to consider that a scenario where EVERY SINGLE INDIVIDUAL after some point in the future, experiences reduced individual lifetime consumption, due to debt incurred by past INDIVIDUALS who experience an increase in their lifetime consumption.

So he is arguing debt has effects transfers don’t.

???

Oops, I forgot to add a sentence fragment:

“For the life of me I cannot understand why you refuse to consider that a scenario where EVERY SINGLE INDIVIDUAL after some point in the future, experiences reduced individual lifetime consumption, due to debt incurred by past INDIVIDUALS who experience an increase in their lifetime consumption…is a reasonable interpretation of “debt burdening future generations”.

Seriously, if you told me that X occurred, and that this X resulted in individuals in the present consuming more over their lifetimes, and individuals in the future consuming less in their lifetimes, then I will say that the initial generation burdened the future generations.

If you then insisted that there is no cross sectional change to wealth, then I will tell you to go take a long walk off a short pier (and into a nice lake of pure high quality beer), because I don’t care if some abstract aggregate statistic doesn’t change, I am looking at the fact that EVERY SINGLE INDIVIDUAL in the future will experience a lower standard of living because of X, and that this means X can be identified as the mechanism for it, and those who brought X about can be blamed for it.

Think in terms of methodological individualism, and you’ll see how there is a burden on future generations of individuals.

Does Krugman think that the Santorum Amendment wouldn’t be a burden on people whose names begin with the letters L through Z? If not, then I don’t see what the example is trying to show.

Ken B.

Does this make America as a whole poorer?

Does it make America as a whole richer?

Since it doesn’t, what’s the point of handing out $5,000?

It’s to make some richer at the expense of others.

So there’s no point in appealing to “America as a whole”, when the program was never intended to effect “America as a whole” to begin with.

Does this make America as a whole poorer?

Does it make America as a whole richer?

Since it doesn’t, what’s the point of handing out $5,000?

guest, I’ve been asking this same question, but from the other side.

There was no reason, in the steady-state apple economy, to borrow to begin with. (A zero-sum game.)

The point of borrowing in a depressed economy (if you’ll allow a Keynesian perspective, for the sake of argument) is not just less pain in the short-run, but that doing nothing will make the short-run and long-run converge. (The longer someone is out of work, the less likely they’ll be to return to work. Or cyclical output gap eventually become a structural one.)

At full-employment with balanced trade, no one, I know, outside of some MMT types has suggested continuing to run budget deficits. (With the possible exception of “worthwhile projects” (that past the cost/benefit test) or WWII type situations.)

anon,

But if the cause of the depression was massive misallocations of resources, then borrowing money to continue misallocating resources is going to make things worse.

And in the present, those who we borrowed from are made worse off.

(And in the case of newly printed fiat money, we actually export our inflation to those who borrow it.)

Full employment, per se, isn’t a noble goal. If we all dig and fill ditches, no wealth is created.

Besides, no one is entitled to a job. Jobs exist because employers think they can earn a profit while making the worker richer than he would have been without the job.

If neither criteria is met, then the job is not created.

Regarding trade deficits, Ron Paul noted that they only matter under a fiat money system – we wouldn’t worry about it under sound money, such as a physical gold coin standard:

Classic Ron Paul – 1988 Campaign Interview (part 2)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tpp5XOJPGlM

guest, on misallocation of resources.

I’m not sure I completely understand the concept.

In the aftermath of the housing bubble, if the private sector doesn’t have enough profitable investments the government could pick up the slack and in invest in areas that the private sector can’t or wont like public transit, education, or research.

(To me “misallocation of resources” is more of a moral argument about government power, than a sound economic theory. It says that government interference will help some and hurt others by taking “power” away from their decisions, and that when things go bad we must pay for that interference because any addition interference will take more power from individuals.)

(In other words that the misallocation is only misallocation because it’s government influenced, not because those resources don’t exist or can’t be used. But that they may at the margin take some power away from individual decision makers to decide for themselves. Because you can get bubbles and wasteful spending with no government at all.)

On the trade deficit, I’m not sure how that would work. If we’re on the gold standard, and a country we trade with goes off the gold standard, couldn’t we have a depression? Would you say this is because of our “misallocation” or theirs?

The analogy with two states, Texas and New York, only works because they are both under the control of a central government. At least in theory we can’t control what our trading partners do. (At least this is what I’m thinking now, I’m not sure. The video you link doesn’t really explain.)

However with a central bank (and a foreign debt denominated in our currency) we do have a lot of control over the price of the dollar relative to other countries.

anon,

I suppose I could have said “malinvestment”, instead. My bad.

At any rate, what I mean is that entrepreneurs are misled into starting inherently unsustainable projects.

They are misled by artificially low interest rates.

They are thinking of profits in terms of fiat money – but if the fiat money keeps losing value, manifested in price inflation (as a result of monetary inflation), then the costs of production will rise, and those government-stimulated investments will reveal themselves to be unsustainable, resulting in a crash.

So, given the savings/consumption preferences of every individua, prior to a government stimulus, said stimulus would be INHERENTLY unsustainable.

Here’s a good video which explains this:

Smashing Myths and Restoring Sound Money | Thomas E. Woods, Jr.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAzExlEsIKk

As with all system-wide changes to the structure of production, yes.

But it would be short-lived for us, due to our sound monetary system (gold coins).

Keep in mind, though, that a depression would be happening to our ex trading partner, as well. Yet, because they think that printing money equals more wealth, their situation will be far worse than ours.

It should be noted that our current structure of production and our standard of living, in America, is due to our ability to export our inflation onto other suckers.

When other countries adopt a more sound currency (alas, not likely to be gold coins, and therefore inherently unsustainable), we will not have the luxury of paying them in increasingly worthless Federal Reserve Notes.

(Other countries DO need to ditch our fiat money, to be sure. But so do we.)

Ron Paul, back in the day, talked about the dangers of abruptly switching back to a gold coin standard, saying that the chaos that would ensue due to a system-wide collapse of the structure of production would SEEM to discredit the gold coin standard.

Which is why he advocates competing currencies, which will naturally result in the phasing out of fiat money.

Here’s Ron Paul on this issue, in 1983, debating a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Charles Partee:

Gold versus Discretion: Ron Paul Debates Charles Partee

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcm8VvBcUdE

The trade deficit between New York and Texas isn’t even tracked. It’s not a concern.

Nobody thinks to say “That state took our jobs” and we need to boycot them, or impose tariffs on goods imported from New York in order to protect our jobs.

And no one says other states should be forced to trade with us or to maintain a particular trade surplus/deficit.

The reason is because, economically, it doesn’t matter. When two parties freely trade, both parties are better off, other wise the trade wouldn’t happen.

In my opinion, Walter Block does a fantastic job of explaining why trade deficits, qua trade deficits, don’t matter, and why “buy America” actually makes Americans poorer (Hint: It has to do with the benefits of the division of labor):

Defending the Undefendable (Chapter 23: The Importer) by Walter Block

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTT_WHyzZ54

Callahan, I don’t know if you are cognitively incapable of grasping the point of the OLG model, or if you are just blindly siding with Krugman because you want his attention, but you aren’t representing a challenge to the OLG model as a COUNTER-EXAMPLE to the “debt cannot burden future individuals” universal claim.

Insisting that the OLG model’s data entries can be replicated by taxation only, and hence debt is allegedly not what caused the lower lifetime consumptions, is as irrelevant the OLG model, as insisting that because a bullet’s effect on someone’s life can be “replicated” by a spear, or guillotine, or the gallows and hence the flying bullet is allegedly not the cause of the person’s death, is irrelevant to the claim that the flying bullet ended that person’s life.

“Doctor, it cannot be the flying bullet that ended this person’s life, because Callahan claims he can replicate the murder by spear.”

You may believe you are revealing something profound in your silly analysis, but all you’re doing is denying the context of that which you are choosing to criticize.

I think its the govt tax policy not the debt that causes this effect. If they taxed Dave 1 more apple then Christy would consume 200 and so on down the periods.

Also to quibble: I thought you were going to show everyone alive after period 1 losing. In this model both Al and Bob gain.

Also to quibble: I thought you were going to show everyone alive after period 1 losing. In this model both Al and Bob gain.

(1) No, I was always very careful to say “everyone BORN in period 2 and thereafter”. I literally capitalized it in my wager to Ken B.

(2) I can of course have Old Al exclusively benefit. But I was afraid Daniel Kuehn would then say, “Oh, but Young Bob loses. So it’s redistribution within generations, just like Krugman said all along.” The great benefit of this setup, where Al and Bob benefit while everybody else (until debt is paid off) loses, is that clearly the two people alive in period 1 gain, and every descendant loses. So far as I know, only Gene Callahan has gone on record as saying this is consistent with Krugman’s description.

Yes Bob was careful about the ‘born’ thing — which I was equally careful to reject. That was the whole gravamen of my limits of integration observations.

One more thing Rob: Do you not see how it COULD work to make only Al benefit, until the debt is paid off? If not, then you are really still trapped in the “constant GDP means just redistribution within a time period” trap.

yes, I see how you could use bonds and taxes in such a combination that people consume 200 apples but have lifetime utility below the maximum because of the distribution of their consumption.

It sill seems to me though that in all your model the govt is controlling the distribution of income in each future period via tax/debt policy. When the bond is issued the govt created a situation where there will be a future default or a tax that will affect both someone’s lifetime consumption and their lifetime utility adversely. But who, when and by how much it taxes or defaults is always optional for the govt. And its which option they choose that affects future distribution patterns – not the original bond.

Replace borrowing with taxing, to the same total number of Apples. Call this the Santorum tax. IE in line 4 “G taxes Eddy 97.” We see what Krugman said don’t we, distributional effects? Or what Gene said? Or for that matter, what Ken B said repeatedly?

Plus of course you don’t have one loan here. You have a loan each generation. That’s 65 loans. If we pay the loan off entirely at generation X, with the appropriate tax, then the redistribution ends and the screwing ends with the youngster who paid up, the gen Xer. Which seems to correspond to Kerugman’s claim about what kind of screwing is possible.In gen 3 we tax Old Christy and Young Dave so that they each end up with 100. Christy, who was alive when the last loan was taken out, gets screwed, per PK. But it ends there.

(Aside to Bob: Now you see why I insisted on quantized apples and more than 200 generations in our ‘wager’ …)

Ken, help me out here (seriously): Do you agree that something has to be wrong in the above? Since Al+Bob collectively consume 99 more apples lifetime, and if I ding each succeeding kid 1 physical apple lifetime, then don’t I need 99 such kids to make it all balance out?

So I think something breaks down in the “…” part. For some reason I must not be able to pay down the government debt one apple per period and keep that pattern alive. Do you agree?

Several points. In your example the debt is paid off at the end of the next period and a new loan contracted. This is appropriate since your model does not allow bonds to be inherited. But then you should live with the implication. Let’s say then that no lons in period 2 forward to look at the effect of the loan in period 1 isolated. In period 2 we pay off the loan. Then Young Christie is done out of A apples where A depnds on the interest. And Old Christy gets 50. The burden has been shifted to Young Christy whose lifetime overlaps beneficiary Bob, per Krugman’s explicit comment. So the borrowing shifted to a younger generation whose lifetime overlapped. But it stops there. The NEXT loan can screw the next generation. And you can chain that for as many apples as you have if you reduce the size of the loans progressively.

I think I can reconcile the 65 versus 99 number.

The 99 extra apples you and Al collectively consume are “financed” by current wealth distribution that includes you and Christy, i.e. wealth is redistributed from you to finance Al’s consumption, and wealth is redistributed from Christy to finance your consumption. Now of course this intra-generational redistribution pattern is carried forward, but like you said, there are only 65 generations of 199 lifetime consumption because of the 65 years of TAXES that pay down the debt by 1 unit per year.

Imagine no debt, but for the first few periods there is still the same initial redistribution that makes you and Al collectively consume an extra 99 apples. If the redistribution stops there, then from then on, everyone subsequent to you will consume the full 200 apples in their lifetimes. The initial 99 addition to your and Al’s consumption is not “depreciated” over 99 other individuals in this situation, and this usefully highlights the fact that it’s the debt that is key, not the redistribution per se.

think I can reconcile the 65 versus 99 number.

Maybe MF, but I actually think something is just wrong in the “…” part of the spreadsheet. I fiddled with the numbers on a sheet of paper, and I think something just isn’t adding up. This isn’t about economics, it’s about matrix algebra or something.

Keep in mind the 67 periods thing is only there, because I wanted to pay down the debt one apple per period. So I’m thinking that for some reason, that approach is going to backfire at some point in the “…” part of the spreadsheet.

But, I don’t trust my intuition right now, since it clearly led me astray already…

Maybe try reducing the debt by 65/99 or 67/99 per period, that way, the debt amortization time length will match the 1 less apple consumed per person time period.

Or you could just make the initial loan 99 apples.

MF I’m going to (tonight) do it from scratch, with each guy only having 10 apples per period. I’ll do the whole thing and see the pattern. Then I will be able to tell if there’s something impossible with what I sketched for 100 apples per person per period, or if my intuitions are just clashing because one of them is wrong.

This is how mainstream economics works, kids. (Although the best economists don’t post a result until the double-check to make sure it has no errors. What can I say, I’m in the minor leagues.)

I think there is just an error in your spreadsheet.

The numbers in the left columns appear to follow the rules:

Even periods consumption = (period +1)

Odd periods consumption = (200 – (period – 1)

So period 63 should have Krugman consuming 138 not 103.

and

period 64 should have gene consuming 63 not 98

You can then though go on much longer (for ever?) with everyone only consuming 199 apples.

Right Rob I agree, something is screwy with my table.

The best economists typically don’t publish something every other day, but rather a few times a year.

If you secretly spent 6 months on this, and then said “Hey kids, look what I just cooked up over the weekend”, then you too could make yourself appear to be error free.

All you’re doing is what other economist do in their minds only, and that’s exactly why your blog has more views than the best economists papers (most papers cited in journal papers are not even read by the author who cited those papers)

Your period 64 should be period 98 (but with the values of consumption 1 and consumption2 reversed).

Like this:

http://i.imgur.com/3EKbp.png

“Like this:”

But then all the debts and taxes would need to be redone to make them match the consumption so it looks like it must be something more complex than just the period # being out .

Yup, I didn’t want to touch that BURDEN.

If he wants to reduce borrowing by 1 each period he will need to reduce the repayment by more than 1 in some periods so that borrowing and repayment reach 0 at the right time – I think that is what is broken.

And that may be what happens in the part of the spreadsheet that isn’t shown so it may not actually be broken at all.

Bob, I may have asked you a similar question before, but why does government have to pay 52.3% on the apples that it borrows from Young Bob in the first period? I don’t quite see how you choose this figure.

E.g. According to your utility function, it would only have to pay around an interest of around 16% to maintain our fictional Bob’s lifetime utility.

100^0.8 + 100^0.8 = (100 – 65)^0.8 + [100 + (1 + r)*65]^0.8

=> r = 0.16

Grant, with whole numbers of loans, the lowest I can make the interest rate go is 23.8%, to make Bob willing to lend 80 in period 1 to get 99 in period 2. The pattern I wanted to establish is that Old Bob gets to consume 199 in period 2 with no taxation on him, so it has to be that his loan from period 1 pays off 99.

You’re right, I didn’t need to give him such a high interest rate, to make him agree to the loan. I had him lend 65 to get 99, but he would have been willing to lend up to 80 I think.

How did I get that number? I think it’s because I originally was doing the example with the same SQRT utility, and then realized I couldn’t get Bob to make such a large loan in period 1. So I fiddled with his utility until it worked, and then I think I didn’t (with the new utility function) once again see how much of a loan Bob would give in period 1.

It doesn’t really matter too much, because I’m fine giving Al and Bob humongous boosts to both of their utilities. I.e. I want to drive home the point that–contrary to Gene Callahan–there is a very real sense in which EVERYBODY ALIVE in period 1 gains, at the expense of EVERY PERSON BORN in periods 2 through 66.

Bob, let me see if I understand all this correctly. Since total consumption is held constant each time t, the only way someone can be made worse off at time t is if someone else is made better off at time t. So in that sense, the burden of debt is just a distributional issue. And we could completely negate its effect if at each time t, the government imposed an appropriate redistribution policy. So there is a sense in which debt doesn’t impoverish the country at all. Do I have that right?

You do.

If the government doesn’t pay back interest in actual apples, then each lender is losing the utility of his lent apples for nothing.

Unfortunately, the Apples Model simply defines out of possibility effects on production (by magically retaining a 200/person apple production).

Government-directed debt financing re-allocates production to political, and less productive, use; such that there is less wealth in the future (which is why economic crashes occur, in the first place).

Now, If the government DOES pay back interest in actual apples, then that’s simply unsustainable (with a fixed amount of production), requiring increasingly more apples to be “borrowed” from each successive generation.

Eventually, the government would have to default, making someone poorer.

And we could completely negate its effect if at each time t, the government imposed an appropriate redistribution policy.

I don’t agree with that, no. After Bob dies, the next generations are definitely going to lose “on net” even in raw physical apple terms.

I can’t keep having this argument, guys. If you think the above table (which has an internal problem, but I hope you see the general pattern that is possible) shows that this is all just a matter of making one guy better in each generation while equally hurting the other, I don’t know what to say. The guys alive in period 1 end up having a lifetime greater apple consumption of 99, and their descendants (for many many generations) each have fewer physical apple consumption. And in utility terms it’s the same thing: Everyone alive in period 1 is better off, everybody born thereafter (for the next 65 generations) is worse off.

If you want to say that’s just distributional issues within a given year, and the people alive today can’t impose a burden on future people, I guess I can’t stop you. But no freaking way Krugman’s readers took that message away with them.

To this day, I don’t think Krugman himself realizes that. Dean Baker finally did, and that’s why he punted and switched to empirical arguments about the size of the effect.

Bob, I already gave you the scheme. Tax however you need to get (old) Christy to 100, and (young) Dave to 100. No more redistributions. Now the screwing stops at Christy. And Christy overlapped Bob, just as Krugman noted was possible. But after that point no more screwing unless there are new loans/transfers. And see my response above why immediate retirement is apt for the rules *you* set for the model: no inheritance of bonds.

I just want to point out to everyone: The way Ken B. et al are rescuing Krugman, is to point out that if the government eliminates the debt (through repayment or repudiation) then the screwing of future generations comes to a halt.

This is supposed to embarrass me, in my claim that government debt can harm future generations.

No. We are applying the rules of your model to the claims Krugman actually made. I for one pointed out that in your own exposition there are 65 sequenced loans.

Just take a break Bob, play with that lively precocious boy of yours, have a beer or whiskey, and then come back and read the arguments more carefully.

Seriously, what a load of bollocks.

You are “applying the rules of Murphy’s model” by literally denying the existence of a core assumption of Murphy’s model, which is an EXISTENCE of debt and taxes.

How in the heck can you actually believe you are thinking consistently with his model by eliminating debt?

I think one person does need to take a break, but I don’t think it is who you think it is.

Well then M-F try reading waht Murphy actually wrote. In his model there really are 65 loans not one. And there are reasosn why the model has to do that. Aplly the rules of the model — no inheritance — consistently and you see the initial loan does not have the effect Bob claims. Several commenters have noticed this.

if Bob has a rebuttal to the fact there is actually a sequence of loans, and it is the sequence which lets him move the burden along — just as PK said — then let him rebut.

Well then M-F try reading waht Murphy actually wrote. In his model there really are 65 loans not one.

Whoa… so now there is a caveat we need to add about the maturity of the original loans? I had assumed saying “Government debt doesn’t burden future generations” meant, the net debt after we roll over some of the loans each period. You’re saying no, I have to give you an example with a 65-generation loan in period 1?

Ken, your criticism makes no sense. The model is a counter-example, that’s it.

There are 65 different loans because in the model the taxation scheme is not sufficient to eliminating the initial debt issuance within one lifetime. It would make no sense to put all the taxation in the same period as the debt, because that would be effectively taxation alone. The point of the model is to show the effects of DEBT that has a lifetime beyond one generation.

Taxation alone would not result in future generations of individuals consuming less in their lifetimes. Yes, this is working from the desired conclusion backwards, but this is permitted for the intent of the model.

You keep denying the assumptions of the model, and saying that if those assumptions are dropped, with new assumptions made, then the model doesn’t show what Murphy claims that actual OLG model shows. That is not how to critique a counter-example. You have to take the assumptions as a given, unless they are internally logically contradictory, which, the last time I checked, it is not.

The “rules” of the model are the assumptions of the model, which is debt that lasts beyond one generation. The reason there are subsequent borrowings is to prevent government default, since the taxation is not sufficient each period, which again, is an assumption you have to accept.

It seems to me that Krugman can’t say that debt doesn’t matter, without also saying that the loan didn’t matter to Old Al in Period 1.

Presumably, Old Al is benefitted in his old age by the utility of Young Bob’s apples.

I submit that this utility is lost by Young Bob; and that defining “debt” in such a way as to ignore utility, but defining “loan” so as to highlight it, is merely sleight of hand.

“You’re saying no, I have to give you an example with a 65-generation loan in period 1?”

I’m saying you did not. You made a new loan each period. So I work with what you did.

I also say that *since you specify no bonds to inherit* you have to (and I praised you for noticing that.) I am pointing out though that that has logical consequences, and I am making them more explicit.

But just for fun let’s repeat your chart with one loan, from Young Bob to old Al, with no more payments or transfers for 65 generations. All those losers you identify above? Not losers. 100 each all the way. Last generation? if Gene pays off 65 he’s screwed. But Daniel benefits not Ken B or Hank back in the middle of the pack.

Right, the OLG model assumes no perpetual rolling over of debt, and taxation at some point. In this model, the taxation is every period.

““The present generation can’t impose burdens on future generations by running deficits today. Sure, they can cause redistribution within a given future generation among people who are living simultaneously. ”

Perhaps his readers did not understand this. But that is exactly what is going on in your table.

…along with the crucial component that each and every INDIVIDUAL past a certain generation consumes less over their lifetimes relative to the status quo.

Is that not a burden to people living in the future? Or are we supposed to play word games and insist that nobody can claim that debt burdens future generations, because of some sterile abstract statistic that while unchanged cross sectionally, is unable show each and every individual loses?

Why should future generations of individuals, many who are not even born yet, be satisfied with having lower lifetime consumption, because of some ignoramuses in the past who denied individuality and contented themselves with incurring debt to increase their individual lifetime consumption at the expense of future individuals consumption, because heck, some abstract cross sectional statistic didn’t decrease so word games were played to divert people’s attention away from the possible outcome as shown in the OLG model?

Neither Rowe nor Murphy ever claimed that the magical cross sectional abstract statistic necessarily decreased because of debt (although an argument can be made that it can, and almost certainly will)

Again, if it was possible for us to enjoy more consumption on the expense of future generations, what’s the constraint on this?

Given that there is an infinite number of future generations to come, why can’t Old All eat 5 million apples and have 5 million generations pay it down?

It just seems to me that current consumption is restricted by current production.

5 million years of reduced consumption per person, is still reduced consumption per person.

Beyond this, does it make any sense to suppose that there would only be one generation of people who incurred government debt? If people believed Krugman et al that government debt cannot ever burden future generations, then wouldn’t it make more sense to suppose that debt is incurred EVERY generation?

I don’t think you got my point or are you saying that it is in fact possible for Old All in period 1 to consume 5900003629253839362 apples?

I got the point about current production limiting current consumption, I was just making another, totally off topic and unrelated point that the time of payback doesn’t change the core of the OLG model.

I guess I just didn’t ignore everything else and go full in with your example, because while it makes perfect sense in and of itself, I had trouble seeing the relevance of it, that’s all.

I think the “limit” of the transfer thing is the limit of how much borrowing the government does.

Which is itself limited by current production.

The relevance of it is: if we can create a burden on future generations, how come that burden is limited by our current production rather than their future production?

I can be a burden on my mom but that is ultimately limited by the amount of money she has, not by the money I have.

How about this one:

You would expect the burden we are on future generations to be inversely proportional to our current productition, wouldn’t you? The more we produce ourselves, the less the burden – right?

But looking at Dr. Murphy’s chart it seems that the more we produce today, the bigger the burden tomorrow.

Only if the borrowing increases to match the production increase will a larger production be associated with a larger burden.

In other words, the burden is limited by the borrowing, and the borrowing is limited by the production.

Yes, you could say the burden is limited by production, but that doesn’t entitle you to say that if the production goes up, so will the burden. The missing premise is the size of the debt.

Think about it. Suppose production increased by 5 million times, but everything else, debt, taxes, etc, stayed the same nominally. The burden would be almost imperceptible. It would be like the difference between each future individual consuming 5 million apples over their lifetimes, versus 4,999,999.99 apples.

You are right, I’m sorry.

What I meant to say was if current production goes up, the potential burden on future generation goes up too. Still not easy to explain, don’t you think?

Again, in general burdens are not restricted by the burdener but by the burdenee 🙂

What I meant to say was if current production goes up, the potential burden on future generation goes up too. Still not easy to explain, don’t you think?

I guess so, but then again I see this principle in a lot of places. The size of the state is limited by the production of others that the state depends on. The larger the production, the larger, POTENTIALLY, can the state get. Kind of explains US history, don’t you think?

Again, in general burdens are not restricted by the burdener but by the burdenee

I agree, burdeners are utterly dependent on “burdenees”. The fewer burdenees there are, the fewer burdeners there can be, ceteris paribus.

Put rather bluntly, parasites are limited by the host. If the host disappears, so will the parasite.

The eschatology of human life, IMO, is how to eliminate parasites without sacrificing the hosts. The only way is for the hosts to use lethal defensive force against the parasites, and that requires, at minimum, a specific moral code.

Well that got way left field..

Does no one understand the difference between paying for something and debt financing something?

The guy who provides the means to finance something is not the one who ultimately pays the bill. Financing allows you to do an exchange stretched out over time hence you can use means to pay that are only available later on. Yet of course you are restricted in the magnitude of financing something by the amount that is available at the point when the transactions starts. So if there are only 200 apples in the economy in period 1 then you only can debt finance 200 apples at max in period 1.

skylien wrote:

Yet of course you are restricted in the magnitude of financing something by the amount that is available at the point when the transactions starts.

Right. I mean Krugman agrees that a household can become poorer in the future by borrowing today. Yet what if the household is going to get a quadrillion dollars next year? It still can only consume Earth’s GDP today. So clearly Krugman is wrong for suggesting households can take on debt today and consume out of future income. What a joker.

The burden I can impose on my future self is not restricted by my current salary. Kind of proves my point.

I’m not getting you problem btw. You have been trying to conconvince everybody about this for month but when someone has a question your reaction is ridicule…

“The burden I can impose on my future self is not restricted by my current salary. Kind of proves my point.”

Christopher,I have not said that. I said you cannot borrow more than is available in the entire economy. This is true for you personally and the government.

When did I answer with ridicule on a question?

Debt=Paying later in time (with physical stuff available later in time.)

Young Bob in period one doesn’t pay anything, he provides the means to finance the operation. It is paid for by Christy starting in period 2 onwards. And due to interest for a consumption loan following generations are worse off. Look at the table.

I have to correct myself. Since it is a “consumption loan” you don’t even need interest that a future generation is worse off.

The government borrows 10 apples from Bob to give to old Al in period 1 without interest. Then the bond is rolled over a few times. Finally the government taxes Frank 10 apples to give them to old Eddy then you have following situation:

The people alive in period one (Bob and Al) had an average lifetime consumption of 205 apples. The people alive in period 5 (Frank and Eddy) have an average lifetime consumption of 195.

And that is exactly what people mean when they say the burden off paying for this and that is put on our children if it is financed with debt.

The only way out of this is if you argue like Daniel K that crucial investments like infrastructure are important to grow the economy (implied only the government can do this), and it is only fair to make a future generation pay since they also reap the benefit of this.

Yet a consumption loan that benefits only Al in period one leaves only the burden but no benefit for future generations who may try to dodge it by rolling the debt over and over (just like a game of musical chairs) until the music stops and it is pay day.

Of courrse the government may tax Frank and Eddy each 5 apples to pay off 10 apples to Eddy if you prefer this… (Of course for Eddy this feals like a partial default)

*feels*

The household is the debtor in this scenario, but a future generation is not the debtor for government debt, everyone alive in the economy is, including the creditors.

skylien’s point is tangential. Whether an investment pays off or not is analogous to whether the debt raises or lowers GDP relative to the size of the debt or interest on the debt. Which has been put aside in the model by making GDP constant.

skylien, bondholders are taxpayers. That makes them, at least in part, liable for their own bonds.

“The household is the debtor in this scenario, but a future generation is not the debtor for government debt, everyone alive in the economy is, including the creditors”

Isn’t the future generation composed of everyone alive in the economy including the creditors at that time?

“skylien, bondholders are taxpayers. That makes them, at least in part, liable for their own bonds.”

I know that. That doesn’t change anything I said.

The point is that in period 1 someone’s lifetime consumption in a fixed GDP economy was increased, which means someone has to pay for that. Obviously it is not Bob who is the only other one alive in period 1, since he has higher lifetime consumption as well as 200. Only people with lower lifetime consumption can be the ones who pay for it. So the answer if the present or future generation pays for this is, that it is not paid for in period one, but in periods 2+.

What a splendid point.

But perhaps Bob has a reply. A prior generation already stole inifinty – 100 apples …

Infinity minus 100 = infinity.

Not sure if this is as “devastating” as it seems to be, but there you go.

Well yeah. That’s exactly Ken B’s point.

Christopher: the constraint is that there’s a limit on how much people will lend to the government.

Nick, make the interest 10,000,000% the point still holds.

Make lending zero.

Now the point no longer holds, no matter how high or low current production happens to be.

Debt is the constraint.

Debt is the constraint of what? It doesn’t limit current or future production (in the model).

We’re talking about bringing future production back in time. If the current generation can consume the future’s production, why is their consumption limited by what they can produce today?

I think debt can only limit present or future *consumption* by either bondholder (or (tax/spending) policy choice. (For example the government can spend all the money they borrow on the bondholders they borrowed it from leaving their consumption the same as if they’d not borrowed even if they choose to tax the bondholders later in life to pay for their own bonds.)

Wow. I had just assumed that maybe 3 people existed who still thought this was a “verbal trick” Nick Rowe was playing. Now I see it’s at least four such people. Amazing.

Interesting answer. I don’t get it though.

You certainly don’t have to give me an answer… but why wouldn’t you?

Well, there is no way we can lend the government more than our total income. And we will want to keep some of our income to consume ourselves today. And we will only lend the government a large proportion of our income (and have little left to consume ourselves) if the government offers us a high rate of interest. And even then we will ask ourselves whether the government will actually be willing and able to tax future generations to pay that interest? Because if the government can’t, we won’t be able to get the next generation to buy the bonds from us.

In Bob’s example the binding constraint is Young Christy. She’s only got 1 apple left to consume.

So what you are saying is: we can only burden future generations insofar as we produce today.

If that makes sense to you…

If you want to leave the theoretical realm and enter reality, then no, it is obvious we do burden future generations more than we actually produce. Just take at all the Fed money printing. The money they are creating out of thin air does not represent anything of value, but something of value is going to have to be paid to pay it back.

But this is besides the point. Bob/Nick’s point here is that it is possible for the current generation to burden future generations (in contradiction to what Special K says), not the upper bound of that burden.

It’s possible, but always a choice.

So what you are saying is: we can only burden future generations insofar as we produce today.

…AND insofar as debt is incurred (subject to certain assumptions).

Christopher: basically yes. And we can’t pass on a bigger burden to cohort 10 than the output of the weakest link in the chain from cohorts 1 to 10.

BLEG: If Steve Landsburg or David R Henderson are reading this .. please weigh in.

I think Steve has just agreed to look away in horror since January, like if Protestants see their daughter marry a Catholic boy.

You know him. Ask. Ditto for DRH.

Another fun model:

Assume vegans produce and consume only veggies.

Assume carnivores produce and consume only meat.

“You can’t tax vegans to pay carnivores!”

Yes you can. You tax the vegans, take their veggies to the ominivores, swap it for meat, and give the meat to the carnivores.

Actually, almost all tax/transfer schemes are like this.

But Nick, there were only vegans in your original model with apples! I see you must be backtracking now. Coward.

Bob,

The mistake is in period 2, the government has to borrow 99 apples from Christy (not 65) to pay Bob his principal and interest (99 apples).

After that, everything will cascade down nicely to period 101.

Actually, I just realized this would imply negative interest rates.

It makes more sense to borrow 98 from Christy, at 0%, and tax her 1. Then you can borrow 97 from Dave, and tax him 1, etc.

Then in period 100, there is no more borrowing, just a tax of 1 to retire the debt, which will be down to 1 by then.

Antony no, that’s not a mistake. I want the debt to go down. It was 65 originally, so it can only borrow 64 from her, and taxes the rest.

Antony you can’t borrow from people at 0% (at least not if you don’t tax them when they’re old).

Bob, haven’t real interest rates been negative during our current our current downtown?

Oops, “downturn.”

I think what he means is that you can’t borrow from people at a 0% nominal rate. It is important to focus on the nominal rates because they have solvency implications, which leads to establishing baselines for r and g, and taxation, whereas real rates do not have these implications.

M_F, if the real rate is negative, then nominal r is less than nominal g. (If GDP is constant.)

Yes anon, and people eat more than just apples too. I’m saying in the specific context of what I’m trying to model here, if someone starts with a balanced consumption path, I can’t just take 1 apple away in the early year and give him back 1 apple in the later year. Diminishing Marginal Utility means you are worse off, in terms of lifetime utility. So to get you to lend to the government in the early years, you have to get more in the later years (i.e. positive interest rate).

There could be a negative interest rate in these simple OLG models too, but you’d have to have people getting taxed when they’re old (or having the gifts from nature follow a sporadic pattern). If you were originally going to have, say, (10, 1) then you’d be willing to lend 4 and only get paid back 3, depending on the utility function.

Here is my attempt at a rapprochement.

In his latest post on the subject Gene says:

Young Bob should be indifferent between [using 65 of his apples in P1 to buy bonds] and a scheme that taxes him 65 apples during P1 and (credibly) promises to transfer 99 to him during P2.

I’m going to go out on a limb and agree with this. If Young Bob were as certain that the government would keep its promise about transferring him apples in P2 as he was that it would pay off the bond in P2 then it wouldn’t matter to him whether it used one scheme or the other.

And yet, if we look around we see that governments finance a lot of their spending via debt, and comparatively little through this sort of “tax you now and promise to give you a transfer later” type of system. In fact, all the major examples of the latter type of financing I can think of are cases where the transfer itself is part of the purpose of the program, rather than just being a means of financing.

Why is that?

My answer is that it is harder for the government to make credible promises about future taxes and spending than it is for it to credibly promise to meet its debt obligations. Governments are in fact notorious for making all sorts of promises about what its tax and spending policies will be in the future, and then not living up to them when the future turns into the present.

Granted, governments do sometimes default on their debt, but this is comparatively rare, and the incentives for not doing so are stronger. So governments use debt rather than Callahan-style financing because it is easier to get people to believe they will follow through on their promises.

If that’s right, then it is perfectly sensible for someone to decry the burden growing government debt will impose on our children even though the same result could in theory have been achieved without recourse to debt financing.

As an analogy, suppose a guy shoots up a shopping mall, and in response someone says the incident shows the need for gun control. There are all sorts of counter-arguments someone might make here, but it would be a weak response to simply say that guns are irrelevant because you can also kill people with a bow and arrow. Sure, you can. But practically speaking it’s easier to kill a lot of people with a gun than with a bow and arrow, which is why you see many more cases of mass shootings involving guns than involving archery.

In closing, I hope we can all agree that I am completely right here, and have been all along.

What is this fascination with replicating the debt induced consumption stream, with something other than debt?

You guys are making it seem like if you can that the return on a call option investment can be replicated by longing a put, longing the underlying, and shorting the discounted strike price, that you have somehow proved that the return I got on the call option is not due to the call option I invested in, but rather it is caused by the put, stock, and discounted strike price.

Suppose you and Callahan showed Bob a model on how tax only can induce a consumption stream of data that matches the consumption data in Bob’s debt based model. Would you accept it if Bob then told you guys “Since I can replicate your tax only consumption stream model with this debt based model of mine, it means it’s not really the tax that is responsible for the redistribution and lower lifetime consumptions in your model. So stop claiming it’s taxation that is causing the redistribution!”

———————–

What’s also incredible about Callahan’s “tax plus promise to pay back” idea is that you guys don’t even seem to realize that such a model is just another debt construct, the only difference being that the initial investment is mandatory, as opposed to voluntary.

If the government says “I will give you a choice, you can either voluntarily lend me 65 apples and I will pay you back 99 apples next year, or, I can use force and confiscate 65 apples from you but then promise to pay you back 99 apples next year”, how is that anything other than just taking a regular old debt contract, and adding a mandatory investment caveat to it? That’s not how taxation works, and that’s not how debt works. Before, Callahan was just considering taxes and how because it can “replicate” Bob’s data, it somehow means debt isn’t the cause. Now it seems he’s combining taxes and debt, to form a new concept that is supposed to be a different form of argument from the tax only scenario, despite the fact that it’s still a “because I can replicate the data using another mechanism, you can’t say vanilla debt is the cause in your model.”

You know what I notice? There is this annoying ugly dance bar patron, called OLG…A, and this ugly woman Olga exists, and is right there in the middle of the bar, garnering a lot of attention, inducing frowns and extreme discomfort to the cool cats who regularly visit the place. I also see you, Callahan, Ken B, and recently Dean Baker (he just left the bar), all dancing AROUND Olga, yelling profanities at her, spitting, saying she shouldn’t be there, but you can’t deny that she exists in that bar, and you despise her for that. You all wish that you are going to wake up soon and realize it was all just a bad dream. Yet she persists, like a rotten image of what you believe bar patrons should look like, since you have been taught since who knows when, that this bar is for cool cats only. No WAY can the bouncer ever let this girl in, it should have been IMPOSSIBLE. But Rowe and Murphy brought that ugly woman into the bar, because they want to show everyone that bars CAN potentially contain ugly people, despite history, despite habit, despite what everyone thought they knew about bars.

The ugly woman isn’t leaving guys. Just accept she exists, so that you can all move on with your lives. Rowe and Murphy are getting rather frustrated that you guys refuse to accept that Olga is an actual person.

Everyone in the model by definition consumes an average of 100 apples per period.

Once Al has consumed 165 in period 1 then everyone else must consume less than 100 on average in each period. In total everyone else in the model will consume 65 less.

In the simplest case Bob will consume only 35 in period 1 and everyone else will go on consuming 100 each period.

However as Bob has shown via transfers between the 2 living people in each generation it is possible to distribute that 65 apples over many generations (up to 65?).

Within the model all you are really doing is changing the distribution between the 2 living people in each period. However one can add a narrative where one calls these transfers “bonds” and “taxes”.

If “bonds” are used then an expectations is set that a compensating transfer will take place in the next period with interest to make up for the lost consumption in the previous period. The internal logic of these models shows that “bonds” are unsustainable and will eventually end in either default or taxes that will lead to at least one future person consuming less than 200 apples in their lifetime. I think it is this that leads Bob to conclude that they lead to a burden on the future.

However at the start of period 2 the govt is more or less in the same position whatever the reason for the transfer in period 1. It can default on the bond , or tax either the elders or younger to pay it off, or continue with the unsustainable bond scheme by issuing again to the younger (or a combination of these things)

For this reason I agree with Gene that it is the initial transfer not the bond that causes the “burden” , and the burden consists entirely of reducing consumption to compensate for the extra consumption by Al in period 1.

However at the start of period 2 the govt is more or less in the same position whatever the reason for the transfer in period 1. It can default on the bond , or tax either the elders or younger to pay it off, or continue with the unsustainable bond scheme by issuing again to the younger (or a combination of these things)

But Rob, defaulting will lead to the present generation (borrowers) gaining at the expense of future generations (lenders), and taxation will just make the vanilla OLG model explicit.

You haven’t shown that it’s not the debt that is the burden, in the OLG model.

But Rob, defaulting will lead to the present generation (borrowers) gaining at the expense of future generations (lenders)

This is, at most, backwards. Defaulting, at least in the mode, helps the future generation. (Defaulting could cause other problems like a financial crisis.)

I think you’re close …

In what way does a default help future generations?

And, again, future generations aren’t borrowers or lenders. Bondbuyers are lenders and everyone alive is a borrower, including bondbuyers. (Really everyone alive is a “debtor,” not a borrower, the government is the borrower.)

No. A specific subdivision of the country are borrowers, and another are lenders.

The government is making promises (as if acting as a bank) to the lenders, and there’s no one borrowing from the government.

At no point is the government ever owed anything. In its function as a bank, it is merely facilitating the transfer from a lender to a bondholder.

I should say “a specific subdivision of the country are *bondholders, and another are lenders”.

I’m confusing myself. *sigh*

I mean to say that bondholders are paid back from future lenders/bondholders.

… And that at no point is the government ever owed anything.

Defaulting in period 2 will make the transfer in period 1 exactly the same as if it had been a tax in distributional terms.

Blackladder, but from a Krugman-Keynesian perspective, deficit financing is (I think) more effective in a recession than taxing and spending.

There’s a straw-man aspect to these debates in that they ignore the Krugman position of “deficit hawk,” during normal times.

I think the claim is that deficit financing transfer funds away from those not willing to spend elsewhere, whereas tax and spend hits those willing to spend and those not indiscriminately. (Maybe a “temporary” tax could be appropriately targeted, though, and we can do away with deficit financing.)

“Automatic stabilizers” and falling tax revenue probably complicate the story, but I’m not sure to what extent.

Does it really matter how government gets its revenue, whether it be from taxes, debt or inflation? In any case, they are going to waste it and they used force to get it.

Thieving wasters.

.

Of course this makes all of us poor.