Carlin on Civil War

I would much rather listen to him than a bunch of progressives on Twitter pretending that they knew yesterday when Andrew Jackson died.

Trump on Andrew Jackson and Civil War

Here’s how CBS News reports the latest outrage:

President Donald Trump appeared to misremember some history about President Andrew Jackson before implying that the Civil War may have been unnecessary.

“I mean, had Andrew Jackson been a little later you wouldn’t have had the Civil War,” Mr. Trump said in an interview with journalist Salena Zito on SiriusXM’s “Main Street Meets the Beltway,” which was released Monday. “He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart. He was really angry that he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War – he said ‘there’s no reason for this.'”

Jackson died in 1845, which is 16 years before the Civil War began. Mr. Trump has often talked about the similarities between Jackson and himself, and keeps a portrait of the seventh president hanging in the Oval Office.

Mr. Trump then went on to suggest that the Civil War could have been avoided, and that had Jackson been in power he could have prevented it. “People don’t realize, you know, the Civil War, if you think about it, why?” Mr. Trump said.

“People don’t ask that question, but why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?”

So naturally, people on social media are OD’ing on smugness, pointing out that Trump apparently is cool with slavery. The irony here is that as they lecture Trump on not knowing basic history, they themselves are apparently ignorant of the fact that the US is just about the only country (plus Haiti?) where widespread violence was needed to end legal slavery.

However, there is a further oddity here, where other people are laughing that Trump apparently didn’t know Andrew Jackson died before the Civil War. On this point, I don’t get it. In the quotes I’ve seen, at first it seemed clear to me that Trump’s whole point is that IT’S TOO BAD ANDREW JACKSON DIDN’T LIVE TO PREVENT THE CIVIL WAR. And think the “he was really angry” line means, with the brewing hostilities between North and South that eventually (after Jackson died) led to the Civil War. That is certainly the charitable reading, and possibly the correct one to boot. (EDIT: The smug interpretation–that Trump meant it’s too bad Jackson wasn’t PRESIDENT during the Civil War, as he watched it unfold with horror–is also plausible, upon my re-reading. But initially I thought Trump meant, it’s too bad Jackson died.)

If anybody saw more of the interview, feel free to chime in.

In Honor of the March for Science

I think the progressives really have no sense of self-awareness or irony. For years, a standard talking point among climate skeptics was that government funding made it very lucrative to exaggerate the possible influence of humans on global temperatures. Naturally, the “pro-science” community recoiled in horror at the very suggestion at such a crass motivation. The only time funding matters is when it’s funding coming from Big Oil or Big Tobacco.

Yet when the Trump Administration proposes large cuts in government grants, NPR runs a story warning that researchers may now engage in “sloppy science” even fudging data to keep their labs open. OK fine, but if NPR is going to run this, I hope they don’t pooh pooh the idea that other scientists might exaggerate the danger of climate change to win grant money. Make up your minds, folks.

Follow-Up From Pat Michaels on Jerry Taylor’s Climate Model Argument

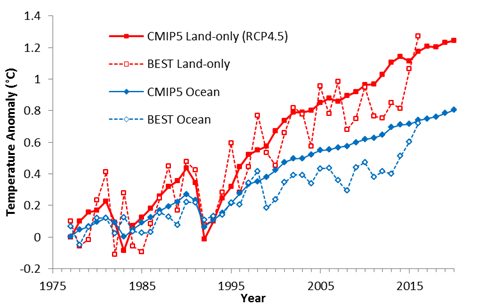

In a recent post, I linked to a 2015 blog post from Jerry Taylor. I was concerned that his own chart showed the opposite of what he claimed. Specifically, it seemed that the climate models that were published in the 2007 IPCC report had overpredicted actual warming from 2007 forward. And since you can calibrate the models (by adjusting parameters such as the reflectivity of aerosols in the atmosphere), the fact that the models “match” the observations before 2007 is not so reassuring.

In a comment at my post, climate scientist (and Cato scholar, and my co-author) Pat Michaels wrote this:

Of course, because of the discrepancy between the models and surface average temperature, the difference between modeled and observed ocean-only readings is large, and post -1998 only matches the models during the recent El Nino (too bad this reply section will not accept an illustration).

There’s the further problem that Taylor tries to sweep away: The satellite/radiosonde comparisons with the IPCC model average show a huge error in the vertical in the tropics. Given that the vertical stratification is what determines tropical precipitation, that means the modeled rainfall is systematically wrong. Given that the presence of surface water dramatically alters the partitioning of incoming radiation (less sensible heating of wet surfaces), that means the daily thermal regime is also mis-specified, which will further screw up the rainfall etc…

At any rate, as shown by Hourdin et al. in the latest Bulletin of The American Meteorological Society, the models are tuned to match the 20th century surface history often with physically unrealistic adjustments, possibly a cause of the huge vertical error.

Because Pat said he wished he could post an image, I emailed him and offered him the option. He took me up. So below is the chart he wanted to post, along with his further commentary:

Many things to note. Even in the land-only, the CMIP model mean tends to be too warm post 1998. You will also see that by showing the real datapoints that the fit looks much less fortuitous than in Jerry’s post. And in the other 70%–the ocean surface—every post-1998 datapoint is below the model average, and it only gets close in the recent El Nino. The consequence of getting the ocean surface warming rate wrong is that means the flux of water vapor is being overestimated (it may be tuned in retrospective mode) for the near term and in the future. The calculated water vapor feeedbacks have to assume the forecast is correct, which it most clearly is not.

That leads to a further speculation: If the water vapor flux is wrong in the models (too high) that means that the models will consistently overpredict temperature, so I would surmise that the only way they can match is if they are tuned. I’m sure you have seen Hourdin et al. in BAMS. And that just scratches the surface, so to speak!

PJM

Pat then added in a final email: “[D]on’t forget to re-emphasize that the models were tuned to match the past which is why they fit El Chichon and Pinatubo.”

Potpourri

==> I have an essay in the Fraser Institute’s report on Canada’s experience with a personal income tax.

==> I point out that the pro-carbon-tax R Street Institute is advising conservatives to fold their hand…right after they pick up their flush.

==> I give a backhanded compliment to Steve Landsburg.

==> Ryan Murphy has an article on how the economics profession–when doing econometric estimates of the “fiscal multiplier”–overlooks the importance of monetary offset. I disagree that it’s important for the authorities to “boost aggregate demand,” but anyway Ryan’s analysis is interesting.

==> Tom Woods has an expert journalist on to talk about the crisis in Yemen.

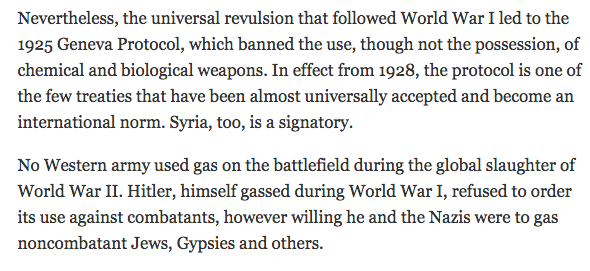

==> This guy in the comments at a Scott Adams post points out something that is quite ironic, in light of the outrage over Sean Spicer’s comments about Hitler vis-a-vis Assad: In late 2013, in a New York Times article about chemical weapons and why Syria’s actions (then) were so outrageous, we have this now-awkward excerpt:

So I’m betting the author of that NYT piece was thinking, “Please don’t go viral, please don’t go viral,” when everybody was denouncing Spicer. (Yes, I understand that NYT piece was more nuanced than Spicer’s initial statement. But the sentiment was the same. Spicer wasn’t “forgetting the Holocaust.” Also, I’m not mentioning this on social media because I don’t want to give anyone the idea that I’m “defending Spicer’s comments,” which were incredibly obtuse.)

Great Celebrity Impressions

Just came across this guy Ross Marquand and his awesome impressions. He is really good at getting facial expressions down too; after you watch the below, check out this.

Careful: A naughty word in the beginning of the below.

Is Jerry Taylor Doing What I Think He’s Doing?

In researching another point, I came across an interesting argument from a 2015 blog post by Niskanen Center’s Jerry Taylor. (It summarized his contribution in a debate on carbon taxes.) It seems that JT is making a pretty bad inference from a chart, but since I’m not predisposed to agree with him, I’m seeking feedback from you folks.

Here’s Taylor:

We also hear quite a bit from the Right about how the computer models have wildly over-predicted warming and thus should not be informing our policy going forward. Again, courtesy of Berkeley Earth, let’s see how the computer models used in the fourth IPCC report (released in 2007) perform when run against Berkeley Earth’s historical temperature record.

The multi-colored lines represent runs from the climate models featured in the fourth IPCC report. The heavy black line represents the Berkeley Earth land temperature record. The heavy red line represents the average of the various model runs. It would appear that the climate models used by the IPCC are now pretty good at replicating temperatures and are not, on balance, running hot.

So my question: If the models were published in 2007, I’m assuming that means they were calibrated up to 2007 (or very recent) observations, right? If so, then the goodness of fit before 2007 isn’t really relevant. What matters is how the models performed out of sample, i.e. from 2007 forward.

And as Taylor’s own chart shows, the models predicted much more warming after 2007, than actually occurred.

So doesn’t this chart prove the exact opposite of JT’s point?

The American Public Only Thinks It Likes Motherhood and Apple Pie

After all, in a big enough apple pie, you would drown.

Scott Sumner has a curious post at EconLog, titled, “The public only thinks it likes low inflation.” He says that such a view is reasoning from a price change, and that low inflation is actually really undesirable–even from the public’s own viewpoint–when it’s caused by tight money.

To make his point, Scott gives (what I think) is a really bad analogy:

[T]he public’s view of the economy fell sharply during the first half of 2008, as an adverse supply shock drove inflation higher. But by early 2009, inflation had fallen to roughly zero, the lowest level of my entire life (since 1955.) And yet the public’s view of the economy continued to fall to extremely low levels.

Some would argue that I am not holding other things equal—unemployment was rising sharply during early 2009. That’s true, but unemployment was rising sharply precisely because tight money was driving inflation down to zero. (It would be like saying the public doesn’t mind falling out of 100 story buildings, just hitting the ground.) The public may say it likes low inflation, but it behaves as if it likes low unemployment.

As I say, Scott’s analogy seems almost exactly wrong for this situation. The reason it’s silly to say “I don’t mind falling out of 100 story buildings, I just don’t like getting crushed on the ground” is that the one just about necessarily follows from the other, at least in normal experience. A more analogous statement would be something like, “I like flying in airplanes, I just don’t like crashing.” And notice that there is nothing absurd about such a statement.

Contrary to Scott’s assertions, high price inflation is bad, per se. To see why, consider this: Would Scott endorse an outcome whereby the Fed locked in perfectly stable–down to the day–NGDP growth, except that the annualized rate of growth was 1 billion percent? I’m pretty sure he wouldn’t. The reason is that the dollar could no longer function as a useful medium of account if prices were rising so rapidly. It would be very difficult to make long-term financial plans at such outrageous rates of price inflation. (I’m assuming real GDP wouldn’t spike accordingly, so that the 1 billion percent of NGDP growth would translate to almost 1 billion percent price inflation.)

In sum, I think the layperson is being quite reasonable when he says, “I would prefer low to high (price) inflation.” Yes, there are scenarios where low inflation goes along with other undesirable things, but that’s true about a lot of goals in life. I recognize that Scott thinks tight money is the great villain in Western economics nowadays, but I think his periodic efforts to convince free-market readers that inflation has gotten a bad rap, miss the mark.

Recent Comments