Klassic Krugman Kontradiction

So there’s a new paper [.pdf], full of regressions, confidence intervals and the like, purporting to show that the Obama stimulus package destroyed jobs on net.

Full disclosure of a busy consultant: I didn’t actually read the paper. From reading this critique by Noah Smith of “Noahpinion” (whom I am going to add to my blogroll, since I like him in the same way that El Guapo was amused by the Three Amigos), it looks like the study may indeed have been fishy.

But my point today is neither to praise nor condemn the paper. Instead, it is to point out a Klassic Krugman Kontradiction. Remember, in a Krugman Kontradiction, he doesn’t actually contradict himself, the way a lesser man might. Instead, Krugman uses true data in order to frame the debate this way or that, always in order to ridicule his opponent, even if he himself is taking the opposite side of an issue from one episode to the next.

So in Krugman’s discussion of this latest stimulus paper, he writes (and I’m reproducing it in full):

STUPID STIMULUS TRICKS

So there’s another the-stimulus-didn’t-work paper (pdf) making the rounds, and as usual being seized on by people who have no idea what the issues are with this kind of estimation.Basically I’m with both Dean Baker and Noah Smith here, but I thought I might add some more general discussion.

What this study claims to do is estimate the effect of the stimulus by looking at cross-state comparisons. So the first thing we should understand is just how difficult it is to do that.

Remember, the stimulus was not big compared with the economic downturn. The original Romer-Bernstein estimate was that it would, at peak, reduce unemployment by about 2 percentage points relative to what it would otherwise have been. And most of that effect was supposed to come through measures that would have been common to all states: tax cuts, transfer payments, etc.. At most, differences between predicted effects among states should have come to no more than a fraction of a percentage point off the unemployment rate.

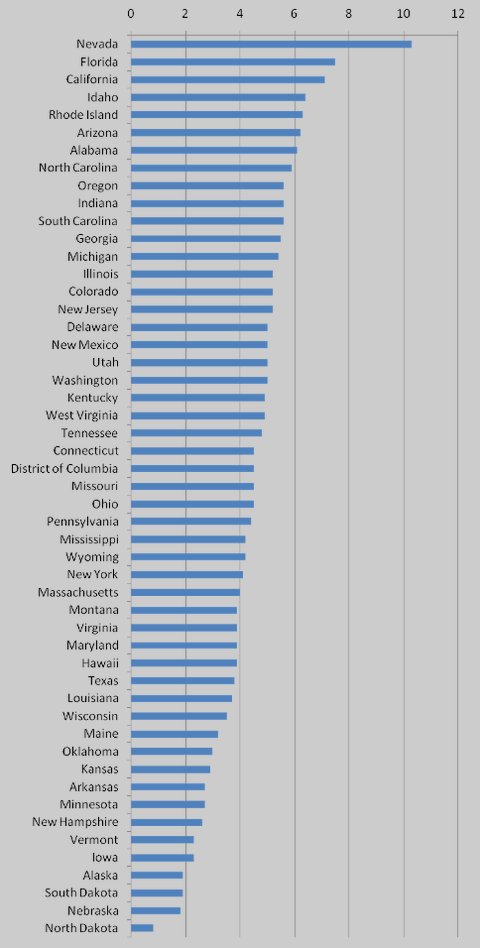

Meanwhile, there were large differences in actual unemployment changes by state. Here’s the change in the unemployment rate from 2007 to 2010:

Obviously there were factors other than the stimulus driving the great bulk of these differences. At the top are the “sand states” that had the biggest housing bubbles; at the bottom, cold places where nobody lives.

To tease any effect of the stimulus out of these interstate differences, if it’s possible at all, would require very careful and scrupulous statistical work — and we’d like to see some elaborate robustness checks before buying into any results thereby found.

The latest anti-stimulus paper shows no sign of that kind of care. It makes no effort to control for the differential effects of bubble and bust. It uses odd variables on both the left and the right side of its equations. The instruments — variables used to correct for possible two-way causation — are weak and dubious. Dean Baker suspects data-mining, with reason; the best interpretation is that the authors tried something that happened to give the results they wanted, then stopped looking.

Really, this isn’t the sort of thing worth wasting time over.

So if you go and re-read Krugman’s post, you’ll note that the one actual argument he spells out–as opposed to mere assertions of dubiousness that may be valid, for all I know–is that these guys didn’t adjust for the housing bubble’s obvious effects on unemployment among the states.

Dean Baker was particularly aghast that these Ohio State researchers could have omitted such an analysis. He went so far as to say:

It also would have been nice to see [in this paper purporting to show that the stimulus destroyed jobs] a variable for the drop in house prices by state. The economics profession as a whole was too thick to notice the $8 trillion housing bubble on the way up, or to realize that its collapse would have any impact on the economy. Now that the collapse of this bubble has led to the worst downturn since the Great Depression, one might think that economists would finally start paying attention to it….At this point, it should be economic malpractice to run state employment regressions without including a housing price variable.

OK, so it’s pretty clear that the pro-stimulus Keynesians can’t believe these moronic researchers didn’t model the obvious fact that unemployment rates across the states were affected by how bad the housing bubble was in each state. I mean, who could possibly have missed that?

In this context, Krugman’s post from December 2008 strikes me as ironic. At the time, he was ridiculing any “hangover theory” of recessions, which blamed out current malaise on the malinvestments of the housing bubble years. Krugman wrote:

So the hangover theory, which I wrote about a decade ago, is still out there.

The basic idea is that a recession, even a depression, is somehow a necessary thing, part of the process of “adapting the structure of production.” We have to get those people who were pounding nails in Nevada into other places and occupation, which is why unemployment has to be high in the housing bubble states for a while….

One striking fact, which I’ve already written about, is that the current slump is affecting some non-housing-bubble states as or more severely as the epicenters of the bubble. Here’s a convenient table from the BLS, ranking states by the rise in unemployment over the past year. Unemployment is up everywhere. And while the centers of the bubble, Florida and California, are high in the rankings, so are Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas.

Incidentally, Brad DeLong liked Krugman’s empirical evidence so much, that he incorporated it into one of his speeches around that time.

Now the problem with the above (note that that BLS link is dated at this point) is that Krugman was looking at the year-over-year change in unemployment across states as of December 2008, whereas the housing bust had been well underway by then. As I pointed out in my reply, if you started your comparison from when the housing bubble burst, then there was a very tight fit in the rankings of states with housing declines and unemployment increases. So the “hangover theory” made a lot of sense, if you did the timing properly.

I guess I should be grateful that Krugman apparently got the lesson. When he wanted to use the obvious connection between the housing bust and unemployment to suit his purposes–as when he ripped the Ohio guys who were attacking the stimulus–Krugman looked at the change in unemployment from 2007-2010, as you can see when Krugman introduces his chart above.

By all means, Daniel Kuehn and others, point out in the comments that strictly speaking, Krugman hasn’t contradicted himself in these two posts. But if you don’t see why he’s being slippery with his opponents, I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree.

Can Government Finances Be Compared to a Household’s?

I think so, in some respects:

Politicians often try to empathize with struggling Americans by promising to cut government spending, “just like regular households in tough times.” This simile evokes different reactions depending on one’s economic views. Keynesians think it’s reckless, proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) think it’s absurd, and Rothbardians think it’s correct as far as it goes, but it falsely equates tax revenues to an honest living.

Mr. Murphy Goes to Washington

On Wednesday, May 25th, I’ll be testifying at the Oversight and Government Reform Committee (chaired by Darrell Issa) at 1:30. The topic will be the connection between Fed policy and high oil prices. The people I’m talking to don’t know right now if it will be televised.

Right now Intrade gives me a 34% shot of causing Bernanke to resign by June 1. We’ll see.

Bob Wenzel Is Golden

My post title is actually a little too conciliatory, because I don’t think Bob’s overall position holds up to scrutiny. But, I definitely misunderstood him in my previous post, and I can’t explain it myself. I was in a Connecticut airport about to board a flight that had been delayed by Air Force One (seriously, that’s what the Delta lady speculated), so I blame Obama for the miscommunication…

Anyway, Bob takes me to task in his latest for “failing to understand the gold standard.” It’s true, I misinterpreted his proposal, and (besides Obama’s visit to Connecticut) the only defense I have, is that I had only read one of his posts, not his first one attacking the Heritage Foundation’s Ron Utt.

First of all, let me reiterate that the issue of the gold being stolen doesn’t really distinguish between the proposals to either sell the gold, or to allow dollar holders to redeem it. Look: Utt said, “The government should sell the gold for $1,400 an ounce and use the proceeds to reduce the deficit.” Wenzel is saying, “No way, that would let the government profit from its theft. Instead of that, I propose that the government make a standing offer to sell its gold for $5,000 [at least] an ounce, to anyone who wants, and then use the money to…?”

Obviously the above aren’t literal quotes, but that is what each man’s position reduces to. So you can see why I pounced on Bob initially and had some fun with it. (Of course, the joke wasn’t too funny since I thought he was doing a firesale, not just restoring redeemability. Oh well, no one said comedy was easy.)

Second and more serious: In the book I co-authored with Carlos Lara, we actually proposed something similar to what Bob is suggesting today. Namely, I said that Bernanke should tomorrow hold a news conference and announce that in one year, he will peg the dollar forever to gold at $2,000/ounce. In the meantime, he would take the maturing bonds on the Fed’s balance sheet and use the proceeds to accumulate gold, rather than rolling it over into more Treasuries. As the date approached for the peg to kick in, Bernanke would have to adjust the overall size of the Fed’s balance sheet to make the market price of gold move toward the target price of $2,000/ounce.

So contrary to Bob, I’m not opposed to reintroducing the gold standard. However, I don’t think Bernanke is going to do that anytime soon, and so I’m also a fan of the government selling off its assets and not raising the debt ceiling.

There is no clean, purely libertarian answer to how to wind down a bloated government. Yes, FDR ripped people off back in 1933, but I don’t think there’s any way to undo that now, at least with respect to dollar holdings. Instead, you’d have to go look at the records and figure out which people were stuck turning over gold at $20.67 in 1933, and then calculate how much they got screwed, and then do whatever formula you wanted and carry their estates forward to figure out the current heirs of those reparations. In other words, you couldn’t just do something with the gold and current dollar holders.

It’s also true that no matter what the government does in practice, it is going to be corrupt and benefit the fat cats. If the government sold off billions in assets, it would give sweetheart deals to the buyers–no question. But at least it would get those assets back into the private sector. I am open to suggestions for better versus worse ways to privatize, but I think it’s a bit shortsighted to say, “Nope, I foresee a way this particular suggestion would be corrupted, so it’s off the table.”

The reason I am in favor of Utt’s idea is that I want a few of the Tea Party Republicans to hold tight on the debt ceiling. Geithner et al. are telling everybody the world will end if Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling, but as I pointed out to The Judge, that’s simply false. They just need to cut spending by a little bit, and they could make up the gap by selling off assets. Yes I would rather they cut spending down to $0. But I am not an all-or-nothing kind of guy; I will applaud moves in the right direction. It would be fantastic if Congress didn’t raise the debt ceiling, slashed spending by (say) $200 billion, and raised the remaining $550 billion or so by selling (a) $300 billion worth of gold, (b) $50 billion worth of oil out of the SPR, and (c) $200 billion in offshore mining rights.

A lot of this stuff isn’t so much because it will actually happen, but it’s good for various pundits to bring them up just to see the politicians and bureaucrats invent bogus excuses. E.g. the Wall Street Journal recently had a piece detailing how many hundreds of billions the government had in assets, like gold, oil, and student loans, but that Geithner refused to consider selling them because he didn’t want to “disrupt the financial markets.” And the context was Geithner’s insistence that Congress needed to raise the debt ceiling to avoid Armageddon.

Another point is that many people are skeptical the government actually has the gold it says it has. So it would also be funny to watch them squirm if the public really got serious about selling off the gold to cover the deficit.

Final point: I would need to look into this more, to see exactly which entity owns the government’s gold. But if the Treasury (as opposed to the Fed) technically owns it, then the two proposals go hand-in-hand: the Fed could go back on a gold standard, and start stockpiling gold by buying it from the Treasury and thus reducing the deficit.

Selling Fort Knox: A Distinction Without a Difference?

Robert Wenzel doesn’t agree with Ron Paul and others (like me) that the US government should sell off its gold in order to close the deficit. Wenzel writes:

Bottom line, it was a series of steps taken by the United States government to obliterate the connection between those holding dollars and their legitimate claim on the Fort Knox gold.

Thus, the gold doesn’t belong to the United States government. It was stolen by contract breach by FDR and the contract was further breached by President Nixon by refusing to redeem dollars by foreign central banks holding dollars.(Note Federal Reserve notes at one time either stated that they were reedemable in silver or gold)

This gold doesn’t belong to the United States government. It belongs to the people holding Federal Reserve notes.

Yep, I totally agree Bob. So what do you propose we do, instead of having the US government sell the gold? Wenzel proposes: “The dollar should be made redeemable into gold for those holding such Federal Reserve notes.”

Now if I wanted to be a funny guy I would just stop the post there. Ha ha. But Wenzel elaborates:

Thus, the call on gold is clear here, it belongs to the holders of US dollars. The current supply of gold owned by the United Sates should be divided by the number of dollars (Some version of M1) and made fully redeemable to those holders.

So I think in practice Wenzel is saying the government should sell the gold at way way way above market prices, in order to stick it to The Man.

For the record, if the government tries to give me an ounce of gold while subtracting (say) $5,000 from my checking account, I will pass on the reparations. Please give my portion to Bob Wenzel.

If, on the other hand, Wenzel is saying the gold should just be given to people, in proportion to how many US dollars they possess (on what date?), then my particular objection falls away, but then I think it raises a bunch of different problems.

Question for David Beckworth

David Beckworth is the poor man’s Scott Sumner, now that the Great Insane One has retired. (Scott himself knows that I say that with respect.) David actually knows quite a bit of Misesian theory (he studied under George Selgin), and so in that respect his defense of Bernanke makes him the Count Dooku of Austrian Economics.

All joking aside, I was dismayed to see David repeating a standard Krugman take in a recent post:

The problem is that the hard money approach–which means tightening monetary policy–makes it next to impossible to stabilize government spending. It also makes it likely the economy will further weaken.

How do we know this? First, in almost all cases where fiscal tightening was associated with a solid recovery monetary policy was offsetting fiscal policy. Last year there was a lot of attention given to a study by Alberto F. Alesina and Silvia Ardagna that showed large deficit reductions were often followed by rapid economic expansion. Further digging by the IMF and by Mike Konczal and Arjun Jayadev found, however, that this was only true when monetary policy was lowering interest rates. Fiscal tightening coincided with a recovery only because monetary policy was easing.

This annoys me for two reasons:

(1) In a standard “crowding out” critique of government deficit spending, the mechanism through which the government siphons resources out of private investment is higher interest rates. (The fact that we have very low interest rates right now is Krugman et al.’s evidence that there is no crowding out!) So how the heck is it a critique of fiscal tightening, to point out that the several successful episodes of it went hand in hand with lower interest rates?! That’s like me saying of Krugman, “Sure, he’s right that rising deficits can sometimes bring an economy out of recession, but those were only in cases where the Fed allowed Aggregate Demand to rise.” (Scott Sumner I think has said that, but again, this is evidence of his insanity, which I define to mean, “Thinking in ways totally foreign to my own approach.”)

(2) I sure hope David isn’t saying that these periods were ones of loose monetary policy because of the falling interest rates. Scott and other quasi-monetarists have bitten my head off several times for making this apparently fallacious leap, and they quote Milton Friedman to beat us Austrians over the head.

The two points are actually related: When David and others say that central banks loosened monetary policy in order to offset the contractionary effects of government fiscal austerity, did they actually look at, say, the scale of central bank asset purchases, or things like M2 etc.? Because the textbook theory of pro-growth austerity would mean that, holding monetary policy constant, a drop in deficit spending would reduce interest rates and thus increase private sector investment.

“What If Ron Paul Was [Sic] President?”

I can overlook the improper use of the subjunctive mood because it’s catchy.

Is Insider Trading Really a Crime?

My sources say no:

[S]uppose a Wall Street trader is at the bar and overhears an executive on his cell phone discussing some good news for the Acme Corporation. The trader then rushes to buy 1,000 shares of the stock, which is currently selling for $10. When the news becomes public, the stock jumps to $15, and the trader closes out his position for a handsome gain of $5,000. Who is the supposed victim in all of this? From whom was this $5,000 profit taken?

The $5,000 wasn’t taken from the people who sold the shares to the trader. They were trying to sell anyway, and would have sold it to somebody else had the trader not entered the market. In fact, by snatching the 1,000 shares at the current price of $10, the trader’s demand may have held the price higher than it otherwise would have been. In other words, had the trader not entered the market, the people trying to sell 1,000 shares may have had to settle for, say, $9.75 per share rather than the $10.00 they actually received. So we see that the people dumping their stock either were not hurt or actually benefited from the action of the trader.

The people who held the stock beforehand, and retained it throughout the trader’s speculative activities, were not directly affected either. Once the news became public, the stock went to its new level. Their wealth wasn’t influenced by the inside trader.

In fact, the only people who demonstrably lost out were those who were trying to buy shares of the stock just when the trader did so, before the news became public. By entering the market and acquiring 1,000 shares (temporarily), the trader either reduced the number of Acme shares other potential buyers acquired, or he forced them to pay a higher price than they otherwise would have. When the news then hit and the share prices jumped, this meant that this select group (who also acquired new shares of Acme in the short interval in question) made less total profit than they otherwise would have.

Once we cast things in this light, it’s not so obvious that our trader has committed a horrible deed. He didn’t bilk “the public”; he merely used his superior knowledge to wrest some of the potential gains that otherwise would have accrued as dumb luck to a small group of other investors.

Recent Comments