That’s My King!

I have some complex theological posts in development, but I’m not ready to post them yet. So let me post this, which I’ve done before:

The Arrogant American Makes a Wager on the Debt Stuff

After spending yet another hour of my life trying to enlighten those of you who still don’t see the debt stuff, what do I get? Gene Callahan still “explaining” why I’m wrong by claiming things about my model that aren’t true.

And, as a special treat, here was the first comment by Daniel Kuehn after my last effort at elucidation:

I still don’t see how you are saying anything more than what Krugman initially said here:

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

This is the cost and the benefit that you’ve shown – costs and benefits on individual children, if you add up their whole lifetime income.

But within each period you don’t have a transfer of resources.

Isn’t this the Krugman position?: winners and losers but no additional burden on any particular future time period?

That’s exactly what your model shows, and what Steve, Gene and I have been trying to point out. Gene was exactly right to point out that your model shows what we’ve been saying all along.

If you look at future income levels, that remains unchanged.

If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”. That’s why I’ve been saying from the very beginning that Nick Rowe (and now you) are saying what Krugman said.

At this point, I am done trying to free you guys from your blindness–now I want to profit from it. So here’s my wager:

Let’s work with my 9-period OLG framework. But let’s be more specific. Assume each person has the utility function of U = sqrt(a1) + sqrt(a2), where a1 is the number of apples the person eats in the first period of life, and a2 is the number eaten when old. (Of course, Old Al has utility function sqrt(a), and same thing for Young John, since they are only alive for one period.)

Now then, I claim that I can construct a scenario in which the following conditions are true. Obviously I am not here spelling out everything about the scenario, but I claim that a scenario exists in which the following are all true statements describing it:

==> The government runs a deficit in period 1 by borrowing from Young Bob to make a transfer payment to Old Al.

==> Al, Bob, Christy, Dave, and Eddy all get more utility in this scenario than they would in the endowment scenario (where everybody consumes 100 each period).

==> Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John all get less utility in this scenario than they would in the endowment scenario.

==> I am just restating the previous two conditions, but let me do it this way so people understand the relevance: In this scenario, anybody who is alive in periods 1, 2, 3, or 4 strictly benefits from the new arrangement, while anybody who is alive in periods 6, 7, 8, or 9 strictly loses from the new arrangement, relative to the endowment scenario.

==> Anybody who lends money to the government does so voluntarily, taking government tax policies as fixed. (I.e. everyone is best-responding to the government’s lump-sum taxing amounts levied in each time period.)

==> The government doesn’t destroy apples; 200 apples are consumed by the two people collectively, in each period.

==> There is certainty; everybody knows the whole model, including all future tax levies, and knows the government won’t default.

==> The government retires its debt by period 9, so that we have a closed system.

If I understand what Daniel is saying above–and what he claims Krugman’s position is–then he must think I am bluffing. After all, the government can make some grandkids poorer, and some richer, but there is no way that deficit financing and lump sum tax transfers within a given time period can make the first five people benefit at the expense of the last five people, right? That’s crazy! I mean, how in the world could it possibly be the case that everyone in the later generations loses, while everyone in the earlier generations gains? There’s not a time machine for crying out loud!! All the government can do is take apples from one guy and hand them to another guy!!

My offer: If Daniel takes me up, then I have one week to convince Steve Landsburg that I have come up with a model that satisfies the above conditions. It’s OK for me if I send him an attempt, and he says, “Nope, you screwed up the interest rate in period 2, your math doesn’t work.” I am allowed to revise the numbers until Landsburg signs off on it. If I do that within one week of Daniel accepting the wager, then Daniel mails me a check for $250.

On the other hand, if a full week goes by and I can’t come up with a model that Landsburg agrees satisfies the above conditions, then I mail Daniel a check for $500.

(If for some reason Steve doesn’t have the time to play these games, I’ll just post it on my blog [assuming I can find such an example] and we’ll hope that the community will be able to tell if I’ve succeeded or not, within the week time limit. I mean, this will basically be a math problem, and just a matter of checking to make sure the apples add up to 200 each time period, that sqrt(a1)+sqrt(a2) is more than 20 for Bob but less than 20 for Iris, etc.)

To keep transaction costs manageable, I’m not opening the wager up to others. It’s Daniel or nothing. However, if Daniel wants to hedge by going in 50% or whatever with some of you, that’s fine; but I’m paying Daniel if I lose, and he’s paying me if I win.

Last thing: If some of you on your own find the solution, I encourage you not to post it before Daniel has accepted the wager. At this point, there needs to be a penalty applied for making me take up so much of my time trying to explain to him why Krugman is totally utterly wrong on his handling of this issue.

So what do you think, Daniel? Am I bluffing?

We Will Not Solve the Debt Issue During This Generation

[Second UPDATE: Gene Callahan wants to be clear that he did acknowledge that he had initially misunderstood Nick Rowe’s model. Now that he gets what Rowe was describing, Gene concedes that it is possible, but points out (correctly) that we can achieve the same impact on everyone in the model through government tax-and-transfer actions, rather than using government bonds at all.]

[NOTE: I have made a few edits for typos and one misstatement–I wrote “9 generations” instead of “9 time periods” when I had Nick spell out his wager–since I first posted this. The below is just the post-correction version.]

Wow this whole debt debate has truly been a formative moment in my life. Seriously, I’m not kidding. I thought that with the crystal clear precision of a specific numerical example, all of our bickering would fall away. Don’t get me wrong: I wasn’t expecting everyone to fold up shop and say, “You win this time Murphy, but I’ll be back!” However, I expected people to say, “Whoa…You’re right Bob, this is a lot more subtle than I had initially been thinking about it. But now, using the very helpful diagrammatic framework you’ve developed, let me show you the points I have been trying to make…” (BTW, some of you have done that with me over email, and I appreciate it. I do it all for the fans.)

Fair warning: This is going to be a long post. If you are a casual reader, you may want to skip it. But I am writing this one primarily for PhD-trained economists, because even you guys (with a few possible exceptions) aren’t seeing all the moving parts on this stuff.

Now let me be clear upfront: As of this moment I am backtracking a bit, and now think that Steve Landsburg’s specific points have all been correct, except when he says that Krugman has been shedding light rather than confusion on this topic. As I will soon explain, Krugman, Dean Baker, Abba Lerner, et al. were thinking about this the wrong way–and so was I in my two book treatments of it. I think Steve has been mystified by my commentary thus far, because Steve has been thinking about these things mathematically, as opposed to using economic intuition. So Since Steve has a formal proof in his head (I’m guessing), he knows that what he’s been saying all along has been correct, and he is just trying to figure out how presumably smart guys like Nick Rowe and I can be making such boneheaded blunders.

Thus, my task in the present post is to wind back the clock, and try to remind people of what they would have thought last week before I entered the fray, and amplified the viewpoints of Don Boudreaux and Nick Rowe. To put it simply, I don’t believe any of you when you looked at my numerical example and thought it was no big whoop. No, it is a huge whoop.

Let me close this preamble with two final observations to try to convince my PhD-holding readers why you should really give me a chance to make my case:

(1) I haven’t been just dabbling on this issue while I go take a smoke break or something. (I don’t smoke, kids, and neither should you. You don’t need nicotine to be cool.) No, Nick Rowe’s original post caused me physical discomfort. I literally couldn’t get to sleep the first night I read it, because I was so sure he was wrong, and yet, there was some little voice warning me that I needed to actually write it out and prove that he was wrong. And when I started trying to do that, it hit me like a brick wall that he was right, and I had been thinking about this stuff the wrong way for at least 10 years. I have probably devoted a good 20 hours to this issue since then.

At my current level of understanding, I realize that there are at least three things tripping people up: (a) Assuming the generations don’t overlap. (b) Assuming that bonds passed on to the next generation must be bequeathed, rather than sold. (c) Assuming government tax-and-spend decisions over time have to be subgame perfect, as opposed to merely constituting a Nash equilibrium. If you have no idea what I’m talking about on each of these points, then I am pretty confident that you don’t realize how subtle this stuff is.

(2) I’m not picking on Gene Callahan, but I just want to explain why I think it’s worth all of our time to catch our breath, step back, and give Nick and me a fairer shake. Nick originally wrote his post, the one that knocked me on my keister. Gene’s initial reaction was to say that the model was “logically incoherent.” Then, I came up with an Excel spreadsheet to clarify exactly what Nick was saying in his largely verbal post. Go read his original post, in light of my spreadsheet, and you will see that I am truly just spelling out what he was describing there.

So: Gene originally said Nick’s post was logically incoherent, I spell it out with a clear numerical example, and then Gene…acts like my example just proves the points he’s been making all along. Nope, sorry, that’s a personal blog foul. It shows that this issue is extremely subtle, and people aren’t giving it the attention that I am saying it deserves. (To be clear, it’s possible Gene et al. have been making other, valid points that Nick and I are missing. But it’s hard to keep track of everything, when people keep saying stuff about our position that is simply not true. Let’s get this stuff down first, and then we can move on.)

Suppose one month ago, Nick Rowe put a riddle/challenge on his blog that went a little something like this:

I have developed a simple model of an economy spanning 9 time periods that has the following properties:

==> People live for two periods.

==> There are two people alive each period.

==> There are 9 total time periods.

==> It is a pure endowment economy with one good (“apples”) with no physical carrying of apples through time.

==> People have standard preferences: They just care about how many apples they eat, they want to smooth consumption over time, etc. There is no altruism and no envy. “No funny stuff.”

==> There is perfect certainty and everyone’s actions form a best-response to everybody else’s actions, including the government’s policies. I.e. it is a Nash equilibrium.

==> If people so choose, they can lend apples to the government, to be repaid the next period (with the revenues coming from either taxation or from borrowing again). However, these bond deals with the government are purely voluntary; a given individual will only do it, if s/he prefers the revised consumption flow to the original endowment flow.

==> There is a single act of taxation in period 9. At that time, the government will take 100 apples from someone, and give them right back to the same person.

==> Relative to the alternate timeline in which everyone consumes his/her endowment each time period, in this instance a person who is alive in time period 1 achieves higher utility while a person who is alive in time period 9 achieves lower utility. Everyone else in the model is either the same or better off, compared to the endowment baseline.

So my wager: I claim that I really am thinking of a model that satisfies all of the above criteria. If you doubt me, then you put up $500 to my $5,000. Call my bluff if you dare. After I get all takers, I will reveal whether I’m bluffing or if I actually have an example satisfying all of the above conditions. I promise, there’s no funny stuff like a person who is worse off because he finds government deficits psychologically distasteful or something goofy like that. Nope, I am either bluffing or I will present a numerical example that you will agree, fits the bill.

Now then, who would have taken Nick up on this offer? I think Gene Callahan would have, because he would have concluded that Nick is being logically incoherent; no such model could possibly exist.

Abba Lerner would have, assuming Nick Rowe is correctly characterizing Lerner’s position.

Paul Krugman would have, because Krugman thinks about this stuff by saying: “Second — and this is the point almost nobody seems to get — an over-borrowed family owes money to someone else; U.S. debt is, to a large extent, money we owe to ourselves.”

Matt Yglesias would have, because he wrote:

A few recent Krugman posts making the point that domestically held government debt doesn’t create a “burden” on the country in the sense of draining it of real resources have proven surprisingly controversial. I think the point can maybe be more clearly made in reverse. Imagine a country with a balanced budget and a large outstanding debt, all of which is held domestically. Tax revenue, in other words, exceeds spending on programs but the extra revenue is needed to pay down the existing debt. If the stock of debt is burdening the country, then it ought to be able to enrich itself by defaulting. Will that work?

Well, no. Certainly a default could set the stage for enriching specific people, since it would create budget room for a tax cut or new spending on a shiny supertrain. But the funds flowing into the pockets of taxpayers or train-builders would be coming out of the pockets of bondholders. A government borrowing money from its own citizens doesn’t gain access to any resources that wouldn’t have been available by conscripting them or raising taxes, and by the same token a country doesn’t enrich itself by refusing to make promised interest payments to its own citizens. It’s only when borrowing from or repaying foreigners that the country as a whole is gaining or losing access to real resources.

And for for sure Dean Baker would have fallen into Rowe’s trap, because Baker wrote:

As a country we cannot impose huge debt burdens on our children. It is impossible, at least if we are referring to government debt. The reason is simple: at one point we will all be dead. That means that the ownership of our debt will be passed on to our children. If we have some huge thousand trillion dollar debt that is owed to our children, then how have we imposed a burden on them? There is a distributional issue — Bill Gates’ children may own all the debt — but that is within generations, not between generations. As a group, our children’s well-being will be determined by the productivity of the economy (which Brooks complained about earlier), the state of the physical and social infrastructure and the environment.

One can make the point that much of the debt is owned by foreigners, but this is a result of our trade deficit, which is in turn caused by the over-valued dollar.

I would have fallen for Rowe’s trap too. Let me walk us all through why I would have, so we can see how our intuition–displayed clearly by Krugman and Baker above, despite Landsburg’s attempt to rehabilitate them–is wrong.

First, I would have dealt with the weird thing about the government in period 9 taking 100 apples from somebody, then handing them right back. I would think, “That’s clearly a wash. It doesn’t hurt or help a person to take apples away and give them right back. If the government took apples from the person and gave them to the other person alive in period 9, then there would be a redistribution, but Nick said that’s not what happens.”

Just to check myself, I might say, “Hey Nick! Can you give me a little more info? How does the other person in period 9 feel about the two scenarios?”

Nick would say, “Sure I’m a sport, Bob. I’ll tell you that–assuming I’m not just bluffing here–I am picturing a model where the other person in period 9 is indifferent between the two scenarios.”

Now I would be sure that I was getting $5,000 from Nick. I would reason this way: “Clearly there is nothing going on in period 9. The government doesn’t change either person’s consumption from the endowment alternative, so it is equivalent to a world where there was no taxing at all. So I’ll just move that issue to the side, and pretend there’s no taxation. Now, Nick said that was the only instance of taxation, and that any other activities are voluntary, and people will only undertake if it makes them better off. Since I’ve just proven that the government isn’t hurting anybody in period 9, and that is the only possible door through which the government in this model could hurt anybody, then clearly Nick is bluffing.”

But wait, $500 is a lot of money after all. So I would think about it some more, and come up with a completely independent argument to convince myself that Nick was bluffing. I would reason this way: “Nick claims that somebody in period 1 is better off compared to the endowment outcome, while somebody in period 9 is worse off, and the only taxing activity occurs in period 9. But he says this is a pure endowment economy, people only live two time periods, and there’s no altruism nor envy. So even if I didn’t already have my first argument, I’ve got this consideration to give me confidence: It is physically impossible for anything done in period 1, to have any connection to something in period 9. There are several generations of people who live and die in between the guy in period 1 who allegedly benefits, and the guy in period 9 who allegedly is the only one who suffers. There isn’t a time machine, for crying out loud, to suck apples out of period 9 and into the mouth of a person in period 1. So for sure, Nick has to be bluffing. I have not one, but two knockdown, bulletproof arguments.”

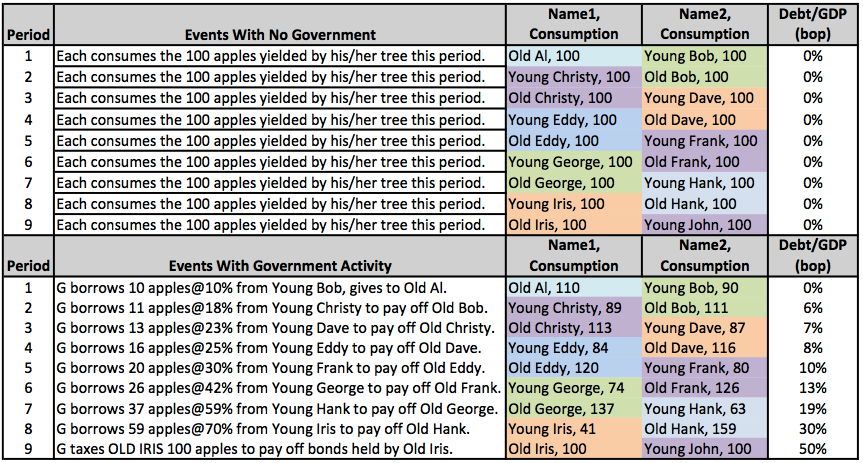

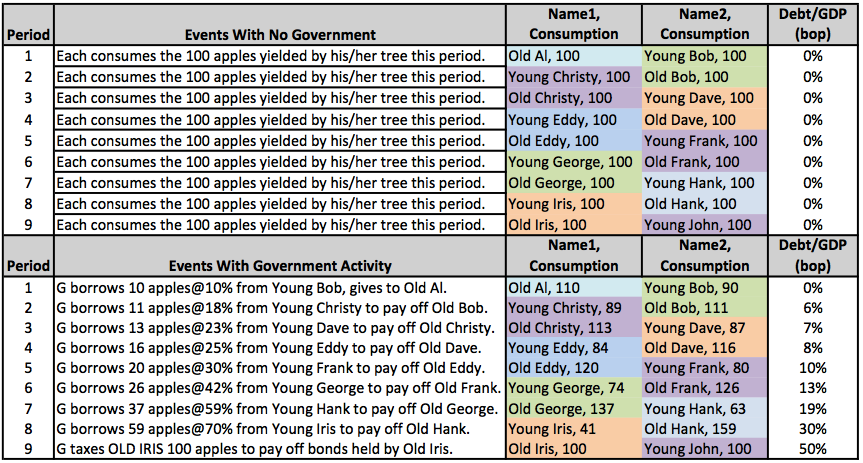

So I would have taken Nick’s wager, and he would have said, “Thanks Bob. BOOM!”:

And, after recovering from the shock/horror/joy, I would have gotten out my checkbook. And, given the quotes I presented above–and their similarity to my “knockdown, bulletproof arguments”–Nick would have collected from Gene Callahan, Abba Lerner, Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and Matt Yglesias. He also would have collected from at least 20 people who have chimed in on all of our blog posts on this topic.

Now I’m not sure if Landsburg would have lost the bet. But I will say this: If I had read Landsburg’s blog post beforehand, it would have encouraged me to take Nick’s wager. Specifically, here are two of the points Landsburg presented in his summary post:

9. As far as future generations are impoverished by the greed of the current generation, their main beef should be not with deficit financing but with the underlying greed. Indeed, a greedy current generation is perfectly capable of impoverishing future generations without deficit spending, by depleting their inheritances.

…

13. On the other hand, even with credit constraints, deficit finance does not allow an entire generation to increase the burden on its descendants beyond what it could have done anyway (and in that sense is nothing like a time machine). It only allows some families to increase the burden on their descendants. The greatest damage one generation can inflict on the next is to consume everything in sight, and this is always possible without deficit finance.

So like I say, reading Landsburg on this issue would have encouraged me to fall into the clutches of the clever Canuck. Points (9) and (13) would have made me think, “Just so, Steve, good job clarifying all this stuff. As Nick makes clear in his alleged example, there is no altruism–so inheritances are always going to be zero, anyway–and it is a physical necessity that each time period, all the apples are consumed by somebody. So I am now even more sure, that Nick is full of it.”

(I’m not going to make this post any longer than it already is, but let me be clear that I actually think Steve’s points [9] and [13] are technically true–even in this specific case–but are highly misleading, as I hope you’ll all agree if you’ve stayed with me this long…)

Yes, it is a huge deal. It’s not merely that Krugman et al. were wrong in letter, they were also wrong in spirit. Look again at that example above: Do you not see how that is EXACTLY what the layperson has in mind, when he says, “It’s not right, us paying for government services that benefit us, by running up big deficits. If we want goodies from the government today, we should have the courage to let them raise taxes and pay for it ourselves, instead of passing the buck down to our kids and grandkids. At some point, that game has to come crashing down, and those poor saps in 100 years are going to be furious at us.”

Despite all of my “bulletproof” arguments, there is like a “wave” that flows down through the generations, from the initial “unfunded” transfer payment in period 1 to Old Al. It’s true, there’s not a time machine, but c’mon, that chart I came up with illustrates perfectly what the average Joe has in mind. In contrast, Krugman et al. have been saying stuff that is not only wrong on the specifics, but is generally misleading and would make the layperson draw the wrong conclusions. Perhaps all of their points work, if we don’t assume overlapping generations, but guess what? That means their result rests crucially on a simplifying assumption that is false, meaning they shouldn’t be trumpeting the result.

Last point to show why this is very important: A lot of you keep saying, “Deficits are functionally equivalent to taxation.” Yes, you’re right, in the sense that I could come up with a complicated scheme with no deficits (involving redistributive taxation in periods 1 through 8 ) to mimic my second scenario above.

But in the real world, it is not at all true that “deficits are equivalent to tax-financed schemes.” Yes, if the government pays old people $1 trillion today, it is “paid for” by redistributing $1 trillion away from young people today (rather than in 100 years). But it certainly makes a big difference to those young people today if they get government bonds in exchange for their present sacrifice of $1 trillion, or if they are simply hit with a tax bill for $1 trillion. The only people who have emphasized this critical point (to my knowledge) are Boudreaux and Rowe, before I came on the scene to be the Thomas Huxley to their Darwin.

Future Generations Will Be Indebted to Me for the Clarity of This Exposition

OK my piece de resistance. I’m going to post this on Facebook, so let me start from scratch:

I am responding to Paul Krugman’s recent claims on why the standard political debate on the government debt is totally wrong-headed. (For a good summary of his position, see this NYT piece.) Specifically, Krugman conceded that if foreigners held U.S. government bonds in (say) 100 years, then those future American taxpayers would indeed be burdened by having to service the debt. However, Krugman said that empirically, Americans basically would “owe the debt to themselves” and so today’s deficits wouldn’t impose a burden, at least not for the simplistic reason that the average fan of Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity would believe.

I would have agreed with Krugman two weeks ago; indeed, in my own textbook I made similar observations. To be sure, I still thought it was irresponsible and would impoverish future generations if the government ran big deficits today, but I didn’t think it was because “hey, our grandkids will eventually have to pay this debt off, and at that time it will be painful to them.”

I was wrong. Krugman is wrong. The difference is, I realized it and–now that the scales have fallen from my eyes–I am the most zealous defender of the layperson’s view on this. The person who made me see the light was Nick Rowe in this post, but now that I understand what the issues are, I realize in hindsight that Don Boudreaux (relying on insights from James Buchanan) was right from the get-go as well. (However, I wouldn’t have seen it by just relying on Boudreaux’s general arguments. It took Rowe’s simplistic thought experiment to finally make it click in my thick skull.)

OK, so consider the following simple world: Every period, there are only two people alive, an old person and a young person. Each person lives two time periods. (I.e. the young person turns old the next period, then dies and is replaced by a new young person.) Each person owns a tree that yields 100 apples to be eaten. The apples can’t be stored for future consumption, and they are seedless so we can’t plant new apple trees. This is what economists call a “pure endowment economy with no physical saving.”

People’s preferences are intuitive. Other things equal, they want more apples in any given time period. There is no altruism nor envy. People also prefer to “smooth” consumption over time. So for example, someone would rather eat (100, 100) apples in periods (t1, t2) rather than eating (99, 101). However, someone might be prefer to eat (99, 105) rather than (100, 100) because the preference for more apples outweighs the preference for smoothing. (I’m being a bit loosey goosey here, but we could make this really rigorous if needed.)

Now consider the following two histories of this simple world:

I need to be quick, so you might need to read some of the links above for the full explanation of this chart. But let me fill in some of my assumptions: In the second example, all of the government’s deficit financing is purely voluntary. I.e. somebody who gives up apples as a young person, for a promise to eat more apples in the future, prefers that stream of consumption to his original endowment possibility of (100, 100).

So compare the outcomes for each person, in the original history versus the second history. Clearly Old Al in period 1 likes the deficit scenario better; he gains. Clearly Young John in period 9 is the same in either scenario; he isn’t affected by the deficits. Also–not as obvious but by stipulation–Bob, Christy, Dave, etc. prefer the deficit scenario to the original scenario. For example, Bob prefers (90, 111) to (100, 100).

So this is looking pretty good, huh? We’ve got a bunch of people who are better off, and one guy who is the same. Looks the government improved the free-market outcome, right?

Oops there’s one person left to consider: Iris. How do you think she feels about this arrangement? Originally she consumes (100, 100). In the deficit scenario, she consumes (41, 100). So she is clearly harmed by this.

But look how I’ve constructed this example. In period 9, the government taxes Iris 100 apples, and then hands them right back to her. So Krugman would look at that and say, “It’s a wash. Iris hasn’t been hurt by the gigantic government debt being passed down through the generations, because in period 9 Iris was unaffected by it–she owed the debt to herself. It’s a total wash.”

Now we can see precisely why that is a silly argument. Sure, if the government handed Iris a bond promising 100, then taxed her to retire the bond, it would be a wash. (We’re neglecting deadweight losses of taxation, etc.) But the government didn’t hand Iris the bond for free, instead it auctioned it off to her in period 8 for 59 apples.

Now somebody like Steve Landsburg is going to look at the chart above and say, “I don’t know why you Austrians keep picking on poor old deficit finance. It gets a bum rap. The real burden imposed on Iris is the taxation in period 9. Her ability to engage in a mutually agreeable bond deal with the government, actually makes her better off than if she were forced to consume (100, 0). So deficit finance actually helps Iris; it’s the taxation that hurts her.”

OK sure Steve, that’s technically right. But COME ON. Once the government in period 1 gives a freebie of 10 apples to Old Al, and doesn’t have the political cajones to directly tax Bob to pay for it, future generations have their fates sealed. As that government debt gets kicked down through the generations, somebody has to get screwed: either the taxpayer who retires the debt, or the bondholder left holding the bag when the government defaults. Depending on the timing, the chickens might not come home to roost until the people who must singly or jointly suffer the brunt of this pain, weren’t even alive when the original transfer happened.

The layperson is basically right, and Krugman et al. are basically wrong. Government deficits today do impose a burden on future generations, because of the “naive” fact that the debt needs to be serviced/repaid. Yes, if the government does something with today’s expenditures that might help our grandkids, then perhaps they will thank us for it. But either way, it is a complete non sequitur to say, “The national debt per se can’t hurt our grandkids, if they owe it to themselves.”

In closing, here’s an analogy of the positions:

LAYPERSON: Whoa, that nutjob went into a restaurant and killed 5 people with a gun.

KRUGMAN: You idiot, you should study physics. Energy is always conserved.

LANDSBURG: Krugman has a good take on this issue, and I would add just one caveat: Guns don’t kill people, bullets do.

Murphy Watching Out for Freedom Tonight

Just finished taping with the Judge. Topic: Paul Krugman and “we owe the debt to ourselves.” Since some of you seem unmoved by crystal clear counterexamples, perhaps my soundbite on Fox will move you.

Another Debt Installment

OK I think I’ve come up with even more obvious ways to make the point. (If you are stumbling on this as an innocent newcomer, see this post and its link to get up to speed.)

Before I do so, I want to be clear on what I’m trying to prove: Paul Krugman and others (a group that would have included me, two weeks ago) think that only the naive layperson could think “running up the government debt allows us to selfishly live at the expense of our grandchildren.” The zinger in their argument is to observe that when our grandchildren are forced to pay higher taxes to service/retire the debt (necessitated by today’s deficits), they aren’t going to be paying us, but rather they will be paying themselves. So–duh!–the layperson can’t possibly be right. Or, more specifically, if the layperson is right, it’s because of complications involving the distortions of taxes, or the distributional impacts of only some people being bondholders, etc. To drive home the fact that it’s the “they owe the debt to themselves” driving his argument, Krugman conceded that if foreigners hold the bonds, then yes, that debt truly is a burden on unborn generations.

Steve Landsburg chimed in to say he basically agreed with Krugman, except that Krugman didn’t go far enough: Landsburg said that even if the government in 100 years owes bond payments to foreigners, nothing really changes.

OK, so here’s what I’m saying: Krugman is totally, utterly wrong. (But again, I would have been equally wrong two weeks ago.) Landsburg ironically is correct, and so I was unduly harsh to him in this whimsical post. Landsburg is right to say that Krugman’s focus on the identity of the bondholders doesn’t really change things. But, what I am saying is that Krugman is WRONG whether foreigners or Americans hold the IOUs issued by Uncle Sam.

In my earlier post involving Abraham and Isaac, I focused on what I think the key issue is. However, lots of people in the comments still aren’t seeing it. So let me try to refine it even more:

There are only two time periods. In period 1, old Abraham has a tree that yields 100 apples. There is also a young Philistine who has a tree that yields 100 apples. In period 2, Abraham and his tree are both dead, but young Isaac is born. Isaac has a tree that yields 100 apples for 1 period, while the (now old) Philistine is still alive, and his tree yields 100 apples. After this period, everything is dead.

SCENARIO 1: The government comes along in period 1, and runs a budget deficit of 10 apples to finance a subsidy to Abraham. The Philistine lends the government 10 apples voluntarily, because it issues him a bond promising 11 apples in period 2.

Period 2 comes along. The government says to the newly born Isaac, “Hi! Welcome to the world. Give us 11 apples or we’ll kill you.” So Isaac complies, and the government retires the bond from the Philistine.

In summary, in period 1 Abraham consumed 110 apples while the Philistine ate 90. In period 2, Isaac ate 89 apples while the Philistine ate 111.

OK, now most people (maybe not Landsburg, because he likes to be difficult), including Krugman, would agree that in this starting scenario, the government in period 1 ran a deficit to benefit the old Abraham, by imposing a burden on the unborn future generation. Yes, the actual financing involved a loan from the Philistine, but he wasn’t really a net loser in the deal. If the layperson looks at that situation and says to Abraham, “You know, your extra 10 apples are coming at the expense of your unborn son,” there is nothing wrong with his analysis. No PhD economist can scold him for being unsophisticated. That is basically correct, and not because of fancy incentive effects or Cobb-Douglas production functions, but for the brute reason that Isaac in period 2 is going to be taxed to retire the debt that made Abraham’s extra consumption possible in period 1.

SCENARIO 2: Tweak things: Suppose in the beginning of period 2, the government defaults on its bond. Now who is harmed? The Philistine, of course. But when was he harmed? I think it’s fair to say he was harmed when the government defaulted. Up until that point–with the expectation that he was going to be repaid–the Philistine was content with arrangements.

SCENARIO 3: OK, now tweak things a different way. In this new scenario, the government doesn’t default; it pays the bond off in period 2. But, right before it does so, Isaac goes up to the Philistine and buys the bond off of him for 11 apples. The government then taxes Isaac the 11 apples, and hands them right back to Isaac to retire the bond (which he acquired from the Philistine 5 minutes earlier).

In this scenario, who “really” shoulders the burden of Abraham’s 10 extra apples in period 1? I think it is quite clearly Isaac. We are effectively back to Scenario 1, where everybody, including Krugman, thought Isaac bore the burden. That brute fact isn’t changed, if Isaac and the Philistine make a voluntary exchange 5 minutes before the government retires the debt.

So now does everybody see why it’s completely wrong to focus on “they will owe the debt to themselves”? In this particular scenario, when the government retires the bond, it is taking Isaac’s apples to give right back to him. Note that if the government defaults in this scenario (after Isaac has bought the bond from the Philistine), it doesn’t help Isaac: He benefits from not being taxed, but now his bond is worthless.

SCENARIO 4: Now we’re going to really tweak things. Throw out the Philistine, and go back to my original thought experiment. Isaac now lives both periods too. In period 1, Isaac lends the 10 apples to the government. In period 2, the government taxes Isaac 11 apples, then gives them right back to him to retire the bond.

In this final scenario, Isaac clearly suffers the burden from Abraham’s extra 10 apples of consumption in period 1. But let’s be more specific: When does Isaac suffer, and in what manner? IT IS NOT in period 1, when he lends the apples to the government. That was a voluntary decision on his part. If you don’t believe me, go back to Scenario 1 above. Quite clearly, we all agreed there that the Philistine wasn’t the one who “really” paid for Abraham’s consumption. Or, at least, whatever way you understood that the Isaac-in-period-2 was getting screwed over in Scenario 1, then that is just as true for Isaac-in-period-2 in Scenario 4. The fact that a younger Isaac lent money to the government in period 1 (in this last scenario) doesn’t alter this fact.

Last thing: In this final Scenario 4, suppose the government defaults in period 2. Well, now it doesn’t hurt Isaac-as-taxpayer, but it hurts Isaac-as-bondholder. Go back to our thoughts of the poor Philistine when the government defaulted on him in Scenario 2. We agreed that quite clearly there, the default hurt him. So, here, the default quite clearly hurts Isaac. Yes, Isaac benefits as a taxpayer, but that doesn’t restore him to equity, as if nothing ever happened.

In Scenario 4, Isaac goes into period 2 knowing he has to be harmed either as Isaac was in Scenario 1 (if the government pays off the bond) or as the Philistine was in Scenario 2 (if the governmen defaults on the bond). Either way, Isaac is getting harmed in period 2, and that’s the true harm that counterbalances the gain to Abraham in period 1. Someone who comes along and says, “No, this is pedestrian micro thinking, because any bonds in period 2 are basically owed to Isaac,” is totally confusing things. It’s not just a little off, it’s totally, utterly wrong to focus on the government taking 11 apples from Isaac in period 2, and then giving the apples right back to him, then concluding, “The burden must lie elsewhere.”

If you don’t like that, try an independent argument:

The government announces that next year, it will whip every citizen 100 times. But, if someone pays the government $1000 today, that person will be spared when the whip-master makes his rounds next year. OK, in this scenario, how is the government raising money today? Because it is threatening to impose harms next year.

New scenario. The government announces that next year, it will take $1100 from each citizen. But, if someone pays the government $1000 today, then the government will exempt that person from next year’s extortion. OK, in this scenario, how is the government raising money today? Because it is threatening to steal money next year.

Final scenario. The government announces that next year, it will take $1100 from each citizen. But, if someone lends the government $1000 today, then the government will issue him a bond that pays $1100 next year, which the person can use to satisfy the $1100 tax bill. OK, in this scenario, how is the government raising money today? Because it is threatening to steal money next year.

Does everybody see what’s going on now, and why Don Boudreaux and Nick Rowe (who were both relying on Buchanan) are right, while Krugman and Yglesias are totally wrong? The government wants to spend a bunch of money today, giving goodies to older people. If it tried to raise taxes to finance it, there would be an outcry. So instead, the government says to some wealthy investors, “OK, we are going to use our guns to extort money from some other people in 20 years. We’ll give you a cut of that loot, if you lend us some money right now to give to the older people so they vote us back into office.”

This is quite clearly a crooked scheme, and if future generations end up holding those IOUs, it doesn’t change the nature of it. There is a very definite sense in which the politically powerful citizenry who enjoy transfer payments due to government budget deficits, are living at the expense of future taxpayers. The layperson is right, and the fancy schmancy economists who doubt this are wrong.

My Resolution of the Dastardly Debt Debate

OK I think I’ve boiled down the issues to their essence. In the debate of Nick Rowe and Don Boudreaux versus Paul Krugman and Matt Yglesias (I’m leaving people out for sure, like Landsburg and John Carney because I’m not sure where to plug them in), the former are basically right. The irony here is that two weeks ago, I would have confidently sided with Krugman and Yglesias. But kung fu master Rowe’s logic was irresistible.

For me, it really “clicked” when I stripped down Nick Rowe’s apple example even more. So think through the following demonstration, and then notice that your objections (which will make sense in this weird world) fall away as we make the scenario closer to reality. In other words, my story below will seem really contrived, but that’s because I’m trying to isolate what I think the real issue is that Krugman et al. are overlooking when claiming “the debt isn’t a burden to future taxpayers if they owe it to themselves.”

So here goes:

Consider a very simple world where there are only two periods, and only two people. In period 1, Abraham has an apple tree that will yield 100 apples. His son Isaac has his own tree, that will also yield 100 apples. In period 2, Abraham and his tree are dead. Isaac is the only person alive, and his tree yields 100 apples. Then Isaac and his tree die too, so that everything is dead by period 3. The apples can’t be stored across periods because they would rot. And there’s no way to plant more trees; Isaac will be dead at the end of period 2, and a new tree wouldn’t be yielding fruit by then.

Clearly, in a world without altruism and just private transactions, there are no trades. Abraham eats 100 apples in period 1, while Isaac eats 100 apples in period 1 and also in period 2.

Now suppose there is a government (which is run by Skynet I guess, since there are no other humans). In period 1, it has 0 taxes but gives Abraham a “greatest generation” bonus payment of 10 apples. It finances the 10-apple budget deficit by issuing bonds. At a 10% interest rate, Isaac’s intertemporal preferences lead him to voluntarily give up 10 apples in period 1, for an airtight claim to 11 apples in period 2.

Period 2 comes along. The government institutes a lump sum tax of 11 apples on the citizenry, i.e. Isaac. Then it uses those 11 apples to retire the bond.

In this scenario with the government, in period 1 Abraham eats 110 apples, while Isaac eats 90. In period 2, Isaac eats 100 apples.

Now let’s make some observations about this outcome:

==> Abraham clearly benefits from the government’s actions, while Isaac clearly loses.

==> If the government in period 2 decides to default on its bonds, that doesn’t help Isaac. Yes, he is spared the 11 apples in taxes, but then he doesn’t get the 11 apples in payment that led him to lend apples in period 1.

==> Yes, there is a definite sense in which Isaac “really” paid for Abraham’s 10 apples of higher consumption back in period 1. But, if Isaac views the government’s actions as exogenous–i.e., it is definitely going to tax him 11 apples in period 2, end of story–then he really is voluntarily buying the government bond in period 1. From his individual, micro perspective, Isaac really isn’t harmed by lending his 10 apples to Abraham, because he is compensated by the promise of 11 apples in period 2. (If a private party (Jacob) had his own tree and made such a deal with Isaac, we wouldn’t consider it a problem.)

So, in conclusion I think Boudreaux and Nick Rowe are basically right. When the government announces its policy in period 1, Isaac thinks, “Oh cr*p. I’m going to get slapped with an 11-apple tax next period. That is going to hurt me then. Right now it’s just a future burden. So, how can I deal with it? Well, maybe I should start saving more. I know! I’ll trade 10 of my apples out of today’s crop, to get paid 11 next year. That way, I can still consume 100 apples next year after taxes.”

It’s good that we had this discussion, and Krugman et al. are right that the average layperson doesn’t get all of the above nuances. But, the average layperson is basically right. Fundamentally, where Krugman et al. go wrong in their “it’s not a burden if the taxpayers owe it to themselves” is just where Boudreaux (relying on Buchanan) thought they went wrong: It ignores the fact that the government is a distinct entity, and that taxation is involuntary. Once you factor those crucial facts into the picture, you see that in a very real sense, government deficit spending today imposes a burden on future generations, when their taxes are raised to retire the debt. This is true even if, at that time, those taxpayers themselves hold the bonds being retired.

(I could try to say more now, and forestall objections in the comments, but I know that is futile. Like I said upfront, if you are getting hung up with Isaac’s complacency in the above scenario, then realize in reality Isaac is one person among millions. He can’t change government policies.)

Murphy, Former Disciple of Abba Lerner

I think I’ve got this debt stuff resolved, after spending about a week on an intellectual odyssey. This is truly one of the biggest shifts in my thinking on something that I thought I had down pat, in my life.

First, let’s go to Nick Rowe’s taxonomy of the various positions one could hold on government debt:

There are 4 possible positions to take on the debt. One of them doesn’t make sense; the other 3 do. Which of those 3 is right is an empirical question.

Here are the 4 positions. I gave each one a name. I made up the quotes.

1. Abba Lerner. ‘The national debt is not a first-order burden on future generations. We owe it to ourselves. The sum of the IOU’s must equal the sum of the UOMe’s. You can’t make real goods and services travel back in time, out of the mouths of our grandkids and into our mouths. The possible second-order exceptions are: if we owe it to foreigners; the disincentive effects of distortionary future taxes; the lower marginal product of future labour if the future capital stock is smaller.’

2. James Buchanan/uneducated person on the street. ‘The national debt is a burden on future generations of taxpayers. Foreigners are basically irrelevant. Any second order effects of distortionary taxes and lower capital stock are over and above that first order effects of the taxes themselves.’

3. Robert Barro/Ricardian Equivalence. ‘The national debt is not a burden on future taxpayers (except for the deadweight costs of distortionary taxation) but only because ordinary people take steps to fully offset the burden on future generations by increasing private saving to offset government dissaving and increasing bequests to their heirs to offset the debt burden.’

4. Samuelson 1958. ‘If the rate of interest on government bonds is forever less than the growth rate of the economy, the government can run a sustainable Ponzi finance of deficits, where it rolls over the debt plus interest forever and never needs to increase taxes, so there is no burden on future generations.’

I personally was taught 1 as an undergraduate. And I believed in 1 until about 1980, when I spent some time reading Buchanan and Barro arguing with each other. And I worked 4 into my own beliefs soon after.

And now, I believe 1 is false. The truth is some sort of mixture of 2,3, and 4. What precise mixture of 2,3,4 is true is an empirical question.

Now, the awkward part. Here is how I handled this issue in my introductory textbook:

Government Debt and Future Generations

In popular discussions, opponents of government deficits often claim that they represent theft from unborn generations. The idea is that if the government spends an extra $100 billion to make voters happy but without “paying for it” through raising taxes, then the present generation has gotten to enjoy an extra $100 billion whereas future taxpayers will have to bear the cost. Is this typical claim really right?

As with the popular association of government debt and inflation, the answer is nuanced: Yes government deficits do impoverish future generations, but no they don’t do so for the superficial reason that most people believe.

When thinking about any debt, be it government or private, keep in mind that all goods are produced out of present resources. There is no time machine by which people today can steal pizzas and DVDs out of the hands of people 50 years in the future. If the government spends an extra $100 billion to mail every voter a lump sum payment to go spend at the mall, it doesn’t matter whether the expenditure is financed through tax hikes or borrowing. Either way, it is the present generation (collectively) who pays for it.

Now of course, in practice there is a difference in how this burden is shared among the present generation, and that’s the whole reason that it’s popular to run budget deficits. If the government raised everyone’s taxes in order to send them all the money back in a check, that would be pointless. But if instead the government borrows $100 billion from a small group of investors and then mails this money out to everybody else, the average voter feels richer.

One way to see the fallacy in the standard “we’re living at the expense of our children” analysis is to realize that today’s investors bequeath their government bonds to their children. It is certainly true that higher government deficits today, mean that future Americans will suffer higher taxes (necessary to service and pay off the new government bonds). But by the same token, higher deficits today mean that future Americans will inherit more financial assets (those very same government bonds!) from their parents, which entitle them to streams of interest and principal payments.

So what does all this mean? Are massive government deficits really just a wash? No, they’re not. The critics are right: Government deficits do make future generations poorer. But the reasons are subtler than the obvious fact that higher debts today lead to higher interest payments in the future, since (as we just explained) those interest payments go right into the pockets of people in the future generations. So here are [three] main reasons that government deficits make the country poorer in the long run:

==> Crowding out. When the government runs a budget deficit, the total demand for loanable funds shifts to the right. This pushes up the market interest rate, which causes some people to save more (moving along the supply curve of loanable funds) but also means that other borrowers end up with less.9 In effect, the government competes with other potential borrowers for the scarce funds available. Economists say the government borrowing crowds out private investment. At the higher interest rate, entrepreneurs invest fewer resources into making new factories, buying more equipment, etc. So long as we make the very plausible assumption that the government will not use the borrowed money as productively as private borrowers would have, it means that future generations inherit an economy with fewer factories, less equipment, and so on. This is a major factor in explaining why government deficits translate into a poorer future.

==> Government transfers are a negative-sum game. Another way that government debt makes future generations poorer is through the harmful incentive effects of the future taxes needed to service the debt. For example, if the government runs a deficit today, and needs to pay back $100 billion to creditors in 30 years, that does indeed make the country poorer at that time. But the problem is not the $100 billion payment per se—that comes out of the pockets of taxpayers, and goes into the pockets of the people who inherited the government bonds. Rather, the problem is that in order to raise the $100 billion, the government would probably raise taxes (rather than cut its spending), and this action would cause dislocations to the economy over and above the simple extraction of revenue.10

==> The option of borrowing leads to higher spending. Yet another danger of government deficits is that they tempt the government into spending more than it otherwise would. Recall from Lesson 18 that all government spending, no matter how it is financed, siphons scarce resources away from entrepreneurs and directs them into channels picked by government officials. Because the public typically resists new government spending less vigorously when it is paid for through higher deficits, the possibility of issuing government bonds leads to higher government spending (and hence more resource misallocation, compared to the pure market outcome) than would occur if the government were forced to always run a balanced budget.

So we see that government deficits really do make everyone poorer (on average), but the mechanisms are subtler than the simple increase in the amount of money the federal government owes to various creditors. But as the bullet points above indicate, the way to alleviate these problems of deficits is to cut spending, not to raise taxes on the present generation! In other words, if the real problems of government deficits are that they take resources out of the present capital markets, and make it more likely that the government will hike tax rates in the future, then it would be no “solution” to close a budget deficit through tax hikes in the present. That would be a cure worse than the disease.

You see the problem. Believe it or not, I was getting ready to write a (qualified) defense of Krugman on all this stuff, back when Don Boudreaux et al. were taking pot shots at him.

But now, due to Nick Rowe’s persistence, I see the error of my ways. It’s not even that the textbook excerpt above is totally wrong, but rather that it is leaving out a huge issue that shows why it’s very misleading to frame matters the way Krugman and Dean Baker (and Murphy!) were doing.

I’ll explain in the next post…

Recent Comments