Ron Paul the Only Antiwar Candidate

I realize I make jokes a lot here, but this stuff is really serious. It is horrifying that every Republican candidate except Ron Paul is talking about “getting tough” with Iran. Can you imagine on September 10, 2001, if you’d told a group of 100 Americans: “Guess what? In a few years we will have Iran virtually surrounded by US troops, either as literal occupying forces or through deals with host governments. Our robot drones will blanket large stretches of land, blowing up people our government wants dead. The US president will say he has the right to kill even US citizens, so long as he assures us the person is a terrorist. When you want to fly from New York to LA, you will have to go into a machine that basically gives a government security agent a naked picture of you.” How many people would think such a transformation would be possible?

And Phil Donahue never made more sense. The Brit had to defend his great leader’s warmaking, but at least Donahue had the courage to admit that he wasn’t courageous enough to be a pacifist.

Bashing Dana

OK watch the beginning of this video clip:

Now people on Facebook were going nuts when this first came out, because the correspondent seems to be openly admitting on national TV that she is worried about Ron Paul doing well.

But something about it didn’t sit right with me. Don’t get me wrong, I full well believe that the people at CNN (and Fox) are terrified at the momentum of Dr. Paul.

What I mean is, it just didn’t sound right to me. She was saying it too matter-of-factly and there was no hesitation afterward. It didn’t look at all like she let something slip out.

I have honestly played this thing once a day since it happened, because I couldn’t put my finger on what was bothering me about the conspiratorial explanation. I couldn’t deny the words that came out of her mouth, but like I said, it just didn’t seem like her tone made sense. In other words, if she had accidentally let it out that she was worried about Ron Paul doing well, I didn’t think it would be with the tone she was using here.

Today it finally clicked with me. Here are her exact words:

Tomorrow, I still, I’m hearing from Republicans, John, who are affiliated with other campaigns, who say they are amazed frankly at how wonderful the Ron Paul organization is, we’ll see if that actually bears out tomorrow. Uh, but in terms of the long term, there’s no question, I’m sure you talk to Republicans, who are worried as well, just like I am, uh that Ron Paul will continue on, long into the spring and summer, and move further, even if he runs as a Republican or an independent…

I put the relevant part in bold. I don’t think she was saying, “I’m sure you talk to Republicans, who are worried just like I am worried.”

Rather, I think she was saying, “I’m sure you talk to Republicans who are worried, just like I am talking to Republicans who are worried.”

To repeat, I’m not denying there is media bias etc. So don’t go ballistic on me in the comments. I’m just saying, this particular clip didn’t make sense to me; the “CNN slips up!!” explanation didn’t sound right.

In contrast, on Fox tonight it was crystal clear what Charles Krauthammer and Bill Kristol were trying to do. Krauthammer was talking about the impact of Ron Paul, and said something like (I’m paraphrasing): “Well he’s obviously not going to be the next president–even Ron Paul admits he’s not actually vying for the White House–but Mitt Romney, if he is indeed the nominee, will have to do something to cater to the libertarian wing of the party. Now it won’t be on foreign policy, of course, but he could do something on the margin, like getting rid of a department or something like that.”

That’s just classic. After telling people for so long that RP isn’t even worth paying attention to, now they can’t go that route because it would be too ridiculous. But they’re still saying it’s “obvious” he won’t be the nominee, and even trying to make it sound as if Ron Paul himself isn’t in it to win it.

“Don’t Count Out Jon Huntsman”

I heard him rallying the troops on an NPR clip. I kid you not, Huntsman actually said with passion, “The people of New Hampshire don’t like to be told for whom they should vote!”

I don’t know whether to laugh or salute. People want a politician who says what he thinks is right, not what he thinks the crowd wants to hear. I don’t know much about his positions, but corrupt backroom deals are not things up with which President Huntsman would put.

My Name’s Bob, and I Have a Debt Addiction Problem

I see my Team Leader has retreated back to his monastery in the snowy mountains up north, to resume his meditations and emerge again only when disaster strikes and all hope seems lost. By the same token, I seriously have a bunch of work I have been neglecting because of all this, so I must force myself to make this pledge: Unless a blogger of at least as much notoriety as Brad DeLong revisits this topic, I won’t do another post on it. I might do mopping up operations in the comments here or at other blogs, but read my lips: No New Debt Blog Posts.

In closing, a few loose ends:

* It is clear that Daniel Kuehn still has no idea what Nick Rowe (and later me) are bringing to this discussion. And I say that, acknowledging that Daniel and I are the MVPs of the two teams, respectively. It’s also true that I was misunderstanding Landsburg and Daniel for much of the debate. Nonetheless, since Daniel thinks Nick’s slogan is goofy, it shows Daniel still doesn’t understand the absolutely critical perspective Nick (and Boudreaux) brought to this issue.

* A few days ago, Daniel Kuehn at his blog announced that he could use deficit financing to flip my result, and make the later generations benefit at the expense of the earlier ones. Gene Callahan declared that this result was, “Game, Set, Match.” However, I pointed out to Daniel that actually, what he was trying to do was impossible, at least within the type of world we’ve been playing with. It’s true, in my simple apple model, you can use government taxing and the bond market to hurt Old Al while helping everyone else (for example). But the way you do it is tax Old Al, then have the government run a budget surplus and lend the apples to young people each time period, at a negative interest rate. (E.g. tax Old Al 64 apples and lend them to Young John at -50%. Then in period 2, the government gets paid off 32 apples and lends them to Young Christy at -50%. etc. In period 9, when Old Iris pays the fraction of an apple she owes the government, it makes a transfer payment to Young John.) So I think Daniel’s interesting attempt to flip my result actually proves that the layperson’s intuition is perfect correct: When the government runs a deficit today, that can allow the present generation to have a higher standard of living by imposing a lower standard of living on all people who will be born in the future. On the other hand, if the government spends less than tax receipts today and builds up a surplus (or pays down debt), then the present generation sacrifices on behalf of future people. There is nothing “naive” in this way of thinking. So go back and look at Gene’s “Game Set Match” post. He said, “I was about to set out building an OLG model in which the later generations benefit at the expense of the earlier ones, but I see Daniel Kuehn has done it for me. That’s it folks, it’s all over. This demonstrates quite plainly that it is the transfers, not the debt, that matters.” Note that to do it right, you have to have negative government debt. So is it really the case that this approach shows that debt isn’t really intimately related to burdening future generations?

* In the last post I asked people to show me a “sentence fragment” where Krugman said taxes needed to finance our debt could make future generations poorer. Let me anticipate one response: Krugman did indeed say that taxes could make them poorer, but he quite clearly was talking about the deadweight loss of distortionary taxes, like say an income tax. That’s why he called it a problem of “incentives.” That’s why, in my simple apple world, there were just lump sum taxes. If instead the government in period 8 (say) taxed people 10% of the apples they picked, then real GDP would be lower in period 8. So Krugman was acknowledging that issue, but he was not at all talking about the possibility of us having a higher standard of living through the wacky bond-market-OLG-framework stuff.

* Finally: I can’t find the link, but at his blog Landsburg was incredulous that Nick Rowe and I weren’t throwing in the towel. Landsburg said something like, “If you guys honestly think Krugman doesn’t believe that deficit financing can make future generations poorer, then why doesn’t he advocate an infinite deficit today? There’s no cost, right?”

There are two answers: First, Krugman was acknowledging that in the real world, there were “second order problems” with deficit finance. For example, our tax code is distortionary. Second–and more to the point–Krugman’s way of thinking also made him believe that there would be no net benefit for the present generation, if they implemented such a scheme. Go back to my apple model, but assume each person just lives one period. In that world, it is correct to say that future generations (collectively) are utterly unaffected by the government in period 1. (Assume people can bequeath government bonds to the people who will be born next period.) So if we recognize that fact, it wouldn’t then follow that, “Oh! So how come the government in period 1 doesn’t borrow 100 apples from Old Bob and pay them to Old Al? You guys just said that the people in period 2 won’t on net be impoverished by this.” Right, but by the same token, the people in period 1 on net won’t be enriched by it: Old Al wins and Old Bob loses. [Later added: And that’s why the scheme wouldn’t get off the ground; Old Bob would never voluntarily lend his money to the government if he has to bequeath the IOUs to somebody who doesn’t care about. Now, if he does care about the next generation, then the government deficit finance helps Bob–it allows him to achieve higher utility. Think about it, kids: Deficit financing is voluntary when it starts; investors have to agree to lend money to the government. So it can’t possibly be the case that government uses deficits to hurt the lenders in order to benefit future people, unless it defaults in the future.]

That’s what’s so funny about all of this. Back when I believed in the Dean Baker-Paul Krugman-Matt Yglesias position on deficit finance, I didn’t walk around saying, “Hey let’s run huge deficits and make ourselves richer, because there’s no burden we are imposing on our descendants!” No, I was telling people, “Don’t think we’re making ourselves richer by running up the debt! Every ton of steel that goes into tanks today, comes out of present resources. We collectively are paying for our government spending, no matter if we’re taxed or they borrow it from us.” See how that all fit together and seemed like a closed book? Until Nick Rowe warped my fragile little mind with his 3-person apple example.

From the Comments: Callahan Joins the CPR Effort on Krugman’s Position

It is amazing to behold people denying that Krugman et al. thought it was literally impossible for us to impoverish future generations. Here is Gene Callahan from the comments:

[I]n other words, does depicting a scenario in which government debt is used to impoverish future generations prove Krugman wrong? I say it does not, since (as Landsburg and I have demonstrated) we can always duplicate your debt scenarios with taxes and transfers. If that is so, then Krugman is correct: it is not government debt in and of itself that is the problem, but rather that seniors may suck resources from the juniors, which they can do via debt issuance, or via other routes.

My response to Gene:

No way, Gene. You show me one sentence fragment from everything Krugman has written on this, where he even hinted to his readers that the present generation could impoverish future generations through deficit finance, but that it wasn’t the debt “per se” doing the impoverishing. He absolutely did not spell out that second part of your and Landsburg’s claim.

Like I have maintained all along, I think the reason Landsburg (and now you) don’t see this, is that you guys never fell for the fallacy. But I did, and that’s exactly why I can tell it is what held (holds?) Dean Baker, Krugman, and Yglesias in its grip.

Look Gene, don’t you see the apparently unbeatable logic behind someone claiming: “Huh? How in the world can Old Bob and Young Al in period 1 do anything that would make people poorer in period 7? No matter what we do in period 1, the people in period 7 earn 200 apples in real income. The government at that time can only take apples from one person and give it to another. It is nonsense to say we can in any way impose a burden on them. All we can do is hand down pieces of paper instructing the government at that time–when we are all long dead–to take apples from one person to give to another. But it’s not like we can make both people in period 7 poorer? How the heck could we do that, without a time machine to suck away their apples so we can eat them now?”

Don’t you guys see the superficial appeal of that type of argument? That is what Krugman et al. were thinking, and not because they’re evil Keynesians, but because it seems right and would be right if there weren’t overlapping generations.

Maybe that will do it, Gene? Do you see how if you are thinking of my apple world without overlapping generations–where everybody just lives one period or everybody lives two periods but at any given time, both people are young or old–then we can’t get this result? In that world, Krugman et al. would be right.

And since nobody even thought this quirk mattered until Boudreaux and Rowe entered the debate, we would still all be thinking through the intuition in terms of “We’re all alive right now, in 50 years we’ll all be dead and our kids will be on the scene, in another 50 years they’ll be dead and our grandkids will be on the scene…”

Does everybody get this yet? I had to use an overlapping generations model to get this freaky result. That’s how it can be possible that the following two claims are simultaneously true:

CLAIM 1: No matter what people in period 1 do with government deficits, the people in period 6 earn a total real income of 200 apples between them. The government at that time can reduce one person’s apple income, to be sure, but only by raising the apple income of the other person alive at that time. Between the two of them, their total real income is fixed by the productivity of the apple trees, not by pieces of paper we leave behind when we die.

CLAIM 2: By running a deficit in period 1, and giving Young Bob an interest income that makes him achieve higher lifetime utility so long as the government doesn’t default, then the government in period 1 and period 2 can ensure that the total lifetime real income of everyone who lives from Christy onward will be lower. The government can, during those future periods, redistribute apples and make the burden hit some people versus others, but the burden is real–Al and Bob have reduced the apple income, collectively, of everyone who comes after them.

At first glance, the above claims seem contradictory. So I wasn’t stupid for not realizing Claim 2 was possible when I wrote my section this in my two books, and Krugman et al. weren’t stupid for missing it a few weeks ago.

Last thing: You guys can settle this quite easily. Ask Krugman very nicely to do a quick blog post telling his readers, “Just to avoid any misunderstanding, by running government deficits today to fund transfers to old people, obviously we can all have a higher standard of living, and impose a lower standard of living, on every single American who will be born in 2013 or later. So sure, in that technical sense, we’d be hurting future generations. You all knew that, right?”

And you guys are telling me in the comments, everyone is going to say, “Duh! Why not tell us the sun rises in the east, Dr. Krugman? Who the heck didn’t know that when you and Dean Baker were saying that the very concept of government debt ‘imposing a burden on our children is especially nonsensical’?”

My FreedomWatch Appearance

Next week, Glenn Beck is going to have me on his show for a full segment to walk his viewers through my 9-period apple model. (Of course that’s a joke.)

I just watched this for the first time. I was worried that maybe I would have said something a little imprecise, since (a) it’s a TV interview and (b) we taped this last week, when my understanding had not advanced to its present Olympian levels. But, at least regarding the Krugman stuff in the beginning, I agree with every word I said.

Debt Financing of Present Transfer Payments: May I Have Another, Sir?

[Note: I’m going to focus on Daniel Kuehn here, because this issue again sheds more light on all this stuff. I realize that we are all still not seeing what each person brings to the table in this debate.]

Ahh, now (I think) I finally get why Daniel Kuehn didn’t accept my wager: It’s not that he totally understood all this stuff from the get-go, it’s that in my wager, from the point of view of period 1, there will still “future generations” that benefited, and “future generations” that lost. So that’s why he was surprised I thought he would deny it. (I had been focusing on the fact that from period 6 onward, every “future generation” was strictly poorer.)

For those who have been following this (I guess you are probably about to get fired at your job, since you haven’t really been working the past week), here is a good sample of what Daniel was saying in response to my “The Economist Zone” saga:

I’ve got to confess I’m somewhat confused about the concern with the ordering of the burdened future generations (ie – cohesive sets of individuals who live across multiple periods with other similarly coherent sets of individuals who live across slightly different periods).

I didn’t think about this until your example either – whether after a certain period every generation carries a lifetime burden or not.

My question is – why does this matter? Who cares if the burden comes after a couple generations that benefit or before? Or perhaps the burden and benefit are alternating. What is the significance of this observation? What’s the value added on top of the fact that we know somebody in the future is going to be burdened?

So like I said, now I think I understand why Daniel can’t understand why I’ve been saying Krugman has totally misled his readers on this (I think unintentionally). Daniel, are you aware that this is possible with debt finance?

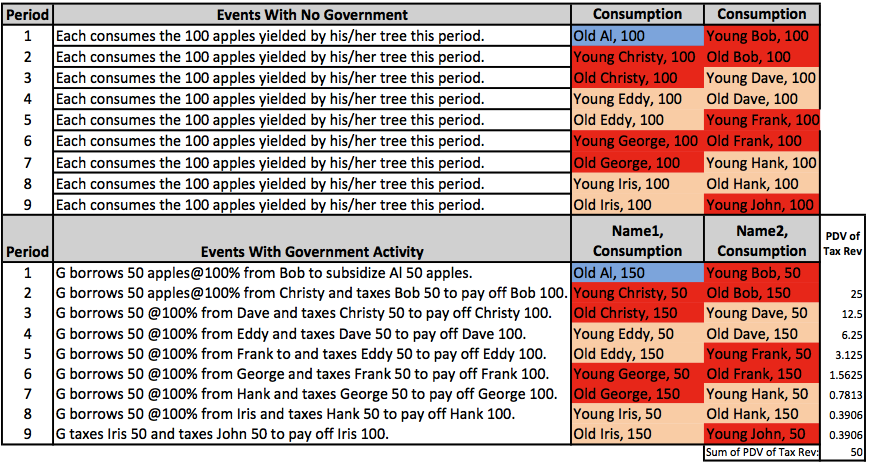

Everyone see how this one plays out? In period 1, Old Al clearly benefits. He gets a government transfer of 50 apples, paid for by a government budget deficit (there is no taxation in period 1).

Also note that I’ve put in the PDV of the tax receipts at each period. See how they sum up to 50 by the end? So one way to understand what is happening, is that the government gives Old Al a payment of 50 apples in period 1, and then spreads the tax burden to pay for it over everybody else (at some point in their lives) in periods 2 through 9. The government uses the bond market to pull all of that revenue forward in time, and give it as a spot payment to Al in period 1.

Now the crucial thing about this particular example I’ve constructed, is that Old Al is the only person who benefits from it, while every other single human being in the country, forever and ever and ever loses in this scenario. And yet, it is still the case that if we take any future time period, the “income earned by our descendants in period x is still 200 apples total.”

So when Krugman (effectively) tells us, “Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants, because the total income they earn in each period will still be 200 apples,” that is extremely misleading.

And in light of the above diagram, I would like Daniel to reconcile it with his frequently stated position: “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.”

So I’m curious, Daniel, how do you reconcile the above outcome by saying, “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose”? No, every single individual in the future loses. That’s why some of us have been jumping up and down screaming, warning people that Krugman is giving very bad guidance on this stuff.

NOTE: If it matters to some people, we could easily tweak the above example so that Old Bob and Young Al get more utility, while every other person from Christy through John gets less utility. Then it would true to say of such a world, “Every single person alive in period 1 benefits from the policies they–and only they–could vote on, while every single person who is born in period 2 or afterward loses, from an initial set of policies over which they had no control since they didn’t yet exist.” But, I didn’t use that one, because I was afraid Daniel would look at Bob benefiting in period 2 and say, “See, in this case Old Bob in period 2 is the guy who benefits ‘in the future.'” That’s why I’m going with my above example, where NOBODY in the future benefits, period.

The Economist Zone

Don’t worry everyone, all that stuff about government debt and future generations is out of my system. After several colleagues have told me repeatedly that I am being obtuse on this, I realize that I’m not cut out for economics and commentary on public policy. Instead, I’ll turn to writing for TV. I have an idea for a new series called “The Economist Zone.” Here’s the pilot. Tell me what you guys think, if you have a few minutes to read it. Thanks.

The scene opens with a million people–all named “Old Al,” oddly enough–looking very sick, and a million other people–all named “Young Bob”–looking very concerned. In addition, there is a politician, and a pundit named David Brooks. Oh, and there are economists–lots of them.

POLITICIAN: The Old Als are weak and dying!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: We need to do something to help them!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

POLITICIAN: They each deserve 3 more apples before they die!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

POLITICIAN: So I’m gonna tax each Bob 3 apples to pay for it!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow 3 apples from each Bob, at a 0% interest rate, to pay for it!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: OK, make it 100% interest! I’ll give each Bob 6 apples back in period 2 if you lend me 3 apples today!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

VOICE FROM BACK OF CROWD: But wait, how are you gonna get the 6 apples to pay us back next period?

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I’ll tax the young Christys 6 apples each!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

VOICE FROM BACK OF CROWD: But wait, we didn’t even want to cough up 3 apples to help our elderly. Why will the million Christys next year agree to a tax hike of 6 apples?

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, because I’ll tell them that if investors ever doubt the willingness of the government to redeem its bonds, then trees will stop producing apples and we’ll all starve!

CROWD: (murmurs)

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow the 6 apples from the young Christys, at 100% interest! They’ll love rolling the bonds over! If you guys want to do it this period, so will they, next period!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

DAVID BROOKS: You should all be ashamed of yourselves! If you want to give our elderly Als 3 apples each, fine, but let’s have the decency to tax ourselves and pay for it. We can’t pass on a huge debt burden to our kids and grandkids.

DEAN BAKER: Don’t listen to him, everyone. Brooks is a fool who does little but eat more than his fair share of apples every year. As a society it is impossible for us to impose government debt burdens on our children. The reason is simple, by period 3 we will all be dead. That means that the ownership of the government debt will be passed on to our children. If we have some huge thousand trillion apple debt that is owed to our children, then how have we imposed a burden on them? There is a distributional issue — Christys’ children may own all the debt while Daves’ children don’t hold any bonds — but that is within generations, not between generations. As a group, our children’s well-being will be determined by the productivity of the trees, which we all know in the real world is forever fixed at 200 apples per period.

Now don’t get me wrong, if our kids ended up owing apples to some hypothetical guys that lived in a different Excel spreadsheet across the ocean, then our kids would be burdened if we borrowed apples today. But Brooks never said a word about this hypothetical possibility, so clearly this subtlety isn’t even on his radar screen.

DAVID BROOKS: Hey I object–!

PAUL KRUGMAN: Well spoken, Dean. But let’s make this empirical for a second: Looking at the data, we see that we live in a closed Excel spreadsheet. There are no apples flowing into or out of our hands or our children’s hands. That’s why David Brooks doesn’t understand debt.

He thinks of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of apples you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt our government creates is basically apples we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.

That’s not to say that high debt can’t cause problems — it certainly can, if our politician were to do something silly like impose a tax that weren’t lump sum (can you imagine?!?). But these are problems of distribution and incentives, not the burden of debt as is commonly understood. And as Dean says, talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay apples to other children, which is a very different kettle of fish.

DAVID BROOKS: You are such a Keynesian scumb–

PAUL KRUGMAN: Please, let me continue. I can see you’re still not getting this. Instead of dealing with a hypothetical example, consider our own history: Remember what happened on the previous tab in this Excel workbook? When our Excel table had that big war with the 9-period orange growers who lived in a different Excel table? Our government emerged from that war with debt exceeding 200 apples; because there was almost no way to move fruit between tables at the time, essentially all that apple debt was owned by people who lived in our table, people like Christy and Dave and Eddy.

Now, here’s the question: did that debt directly make the whole table poorer? More specifically, did it force the table as a whole to have less apple consumption than it would have if the debt hadn’t existed?

The answer, clearly, is no. Yes, some taxpayers in the table had to pay the interest on that debt. But who received that interest? Other taxpayers. Not exactly the same people, of course — maybe Frank had to pay George. But the table was not like a home buyer who has to scrimp to find enough apples to make his mortgage payments; the table was both the borrower and the lender, and was essentially paying apples to itself.

DAVID BROOKS: Huh, I never thought of it like that. And I watch the History channel a lot, where they have documentary after documentary about those evil orange pickers and the big war we had with them. I guess I see what you mean about the Excel table just owing apples to itself collectively…But still, I can’t help worry about us burdening our descendants by passing down a gigantic debt burden that they will have to service.

PAUL KRUGMAN: Look, don’t beat yourself up; we can’t all be trained economists. Try thinking of it like this: Suppose that for some reason the Excel table temporarily ends up being ruled by a guy who is driven mad by power, and decrees that everyone will have to wear their underwear on the outside (sorry, Woody Allen reference) everyone will receive a large allotment of newly printed government bonds, adding up to 500 percent of GDP–that’s 1000 apples, a fantastic sum.

The government is now deeply in debt — but the Excel table has not directly gotten any poorer: the public, in its role as taxpayers, now owes 500 percent of GDP, but the public, in its role as investors, now owns new assets equal to 500 percent of GDP. It’s a wash.

So where’s the problem? Well, to pay interest on that debt, the government will have to raise a lot more apple revenue. Again, this is a wash — the extra apple revenue is matched by the extra apple income people receive as bondholders. Now it’s true, if we imagined some crazy hypothetical world where the politicians implemented taxes that varied based on behavior, then high debt might make the whole Excel table poorer. But fortunately in the real world, we just have lump sum taxes, so this isn’t an issue. Our real GDP–how many apples we produce collectively per period–won’t be affected by this alleged “debt burden” that’s got you so worried will hurt our kids.

DAVID BROOKS: Gosh, I admit you make a lot of sense, but I feel like I’m being hoodwinked. Surely this plan is going to foist a huge debt burden on our descendants. I mean, it has to!

MATT YGLESIAS: Dr. Krugman, sometimes you’re too tied to your academic models. Let me try a different approach on this guy; I know how pundits who have no formal training in economics think. OK Mr. Brooks, Dr. Krugman is correct to argue that so long as government debt is held within our Excel table, then it doesn’t create a “burden” on the table in the sense of draining it of apples. I think the point can maybe be more clearly made in reverse. If a few generations down the road–let’s say in period 7–George and Hank are furious at us for passing on this alleged “burden,” then they can enrich themselves at that time by telling the politician to default on the debt. Will that work?

DAVID BROOKS: Well, no! It won’t, because whoever was supposed to get paid–either George, Hank, or both–will lose out as bondholders! Ha, nice try, Yglesias.

MATT YGLESIAS: (sighs) I can see you’re not a philosopher. You’re correct to point out that it won’t enrich them if the government defaults. But that just shows why your worries are unfounded. A government borrowing apples from its own citizens doesn’t gain access to any orchards that wouldn’t have been available by just raising taxes, and by the same token an Excel table doesn’t enrich itself by its government refusing to make promised apple payments to its own citizens. It’s only when borrowing from or repaying foreigners from other tables that our table as a whole is gaining or losing access to fruit. None of which is to say that debt dynamics are a matter of indifference. Obviously people care quite a lot about which specific people possess the apples. But it’s bad weather or locusts that can immiserate the next generation, not the prospect of the next generation’s taxpayers transferring apples to the next generation’s bondholders.

DAVID BROOKS: I admit, I can’t really put my finger on what’s wrong with your guys’ argument, but to be honest I never really trusted you Keynesians who think we just need to bake some more apple pies for prosperity. I’m going to turn to this guy over here, a trusted Austrian who isn’t afraid to write books on politically incorrect stuff.

BOB MURPHY: You know it’s ironic, Mr. Brooks, normally I can’t stand what these three knuckleheads say about government policy. But in this instance, I think they are technically correct. Although I’m against this deficit spending plan because I don’t think it’s fair that anybody down the road gets hit with an involuntary tax on his apple crop, even so I have to admit that the scheme won’t make our descendants on net poorer. Some grandkids might be poorer because of the tax bill, but–like these guys have been saying–those apples will just go right into the mouths of other grandkids. I mean really, it’s not like we have a time machine, for crying out loud! We can’t literally take apples away from our descendants and eat them today. Every period, no matter what we do, there are 200 apples produced and consumed. All the government down the road will ever be able to do to our descendants is rob one to enrich the other; it can’t make them all collectively poorer than they otherwise would have been. It’s not like we’re dumping chemicals in the soil that will reduce apple output in period 3 or something. It is physically impossible for us to affect what happens to the people collectively in period 9, because we know that no matter what, the two of them will eat 200 apples total. If one person eats fewer because of taxes to service the debt, then necessarily the other person will eat more apples.

Don’t misunderstand me: In a hypothetical world where we could cut back on our apple consumption today, in order to plant more apple trees and raise total apple output in (say) period 5, then this immoral scheme would also objectively make our descendants poorer. But in the real world, where we have no such growth in real output, this isn’t an issue.

DAVID BROOKS: You spend time thinking about hypothetical worlds where apple output increases over the time periods?

BOB MURPHY: Once you start thinking about apple crop growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, I guess that’s that. If the Keynesians and Austrians agr–

DON BOUDREAUX & NICK ROWE: Stop!! This is all totally wrong!! Buchanan showed us why!! There was nothing wrong with your initial reaction, Mr. Brooks! Think of the great-great-grandchildren!!

BOB MURPHY: (puzzled, grimaces, shouts for joy) Yeah! Holy smokes! They’re right! Sorry Mr. Brooks, I was totally wrong. It is possible for our generation to impoverish future ones. Wow this is really neat! Let me walk you through a diagrammatic explanation…

DAVID BROOKS: OK now it’s back to being the free-market guys against the Keynesians. I need a tie breaker. What about you, Professor Landsburg? You’ve always struck me as a pro-market guy who’s still a straightshooter.

STEVE LANDSBURG: Krugman has been saying a lot of good stuff on this. I’m sorry Mr. Brooks, but if you ask me what I think of your fears about a debt “burden” I have to tell you that I think they are idiotic. My only quibble with Krugman is that he’s wrong to focus on whether the government bonds are held by Eddy, Frank, etc. Even if the government in period 9 had to ship apples over to a different Excel table, our descendants wouldn’t be burdened by the IOUs floating around at that time. They would essentially be apples they owed to themselves.

DAVID BROOKS: Well that last line makes absolutely no sense to me, but I know you academics like to be deliberately provocative. But OK, you side with Krugman. So you’re saying that these other guys are wrong?

STEVE LANDSBURG: Look, you’re putting me in an awkward position. I’m friends with those guys. But yeah, I mean Boudreaux likes to go read verbal stuff, instead of thinking it through with precise models, and Nick Rowe is a Canadian, so there ya go.

DAVID BROOKS: And this Murphy character?

STEVE LANDSBURG: He’s a nice guy.

DAVID BROOKS: But when it comes to his dispute with Krugman on whether the government debt can be a burden on future generations, do you think Murphy is making intelligent points?

STEVE LANDSBURG: (pause) Bob makes really funny videos.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, I guess that does it. Go ahead, Mr. Politician, let ‘er rip! A round of 3 apples, for all the old timers! And 100% interest income, for all the young people!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

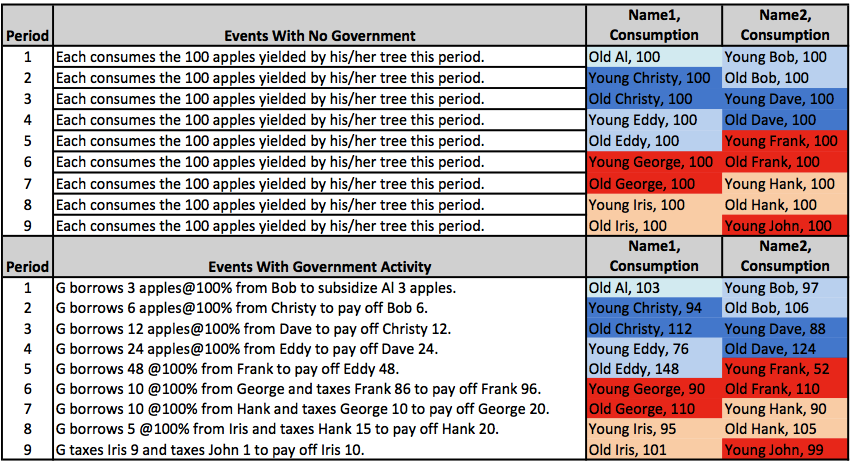

After the decision to give the Old Als 3 apples as a transfer payment, paid for by running a government deficit, events unfold in the following manner:

DAVID BROOKS: (stunned) What the–what the heck just happened?!

BOB MURPHY: Perhaps I can be of assistance. First of all, remember that all of us have the same utility function of U=sqrt(A1)+sqrt(A2). If we had all just consumed our endowments, we would all have 20 utils during our lifetimes (square root of 100 plus square root of 100), with the exception of Old Al and Young John who would only have utility of 10 because they live only one period. Now if you check the math, you can see that Al, Bob, Christy, Dave, and Eddy all have more than 20 utils with their actual consumption patterns, while Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John all have fewer than 20 utils with their actual consumption patterns. Just like Boudreaux, Rowe, and I were saying, government deficits allow the earlier generations to benefit at the expense of subsequent generations.

DAVID BROOKS: (turns to Landsburg, furious) You lied to me!!

LANDSBURG: What the heck are you talking about? Dude, you need to calm down. Try having some more sex, we’ll all thank you for it.

DAVID BROOKS: You told me our debt wouldn’t impose a burden on our descendants. You told me to trust Krugman!

LANDSBURG: Right, the debt didn’t impose a burden. In fact, it helped our descendants.

DAVID BROOKS: What the heck are you talking about?!!?!

LANDSBURG: You’re even thicker than I thought. Check the numbers. Look, take period 7, where Young Hank lends 10 apples to the government. You’re getting hung up on the fact that with his consumption stream of (90, 105), Hank now only gets 19.7 utils over his life, as opposed to the endowment 20. So you’re blaming his loss of welfare on the debt. But no, his reduction in utility is stemming from the tax the government levies on him in period 8. Suppose Hank didn’t engage in a bond deal with the government, and instead just consumed his after-tax endowment each period. He would then consume (100, 85), yielding utility of 19.2. So contrary to your silly assertion, government debt makes Hank better off. It’s the tax that hurt him. Duh.

DAVID BROOKS: But the reason Hank is being taxed in period 8 is to service the government debt!! The government in our Excel table doesn’t tax for any other reason except to service/retire the debt that our generation initially created by giving a transfer to Old Al. So the debt causes the taxes levied on future generations!

LANDSBURG: Whoa, whoa, whoa. I can tolerate a lot of things, but I won’t stand idly by while someone impugns debt finance. You better take that back, mister. Debt didn’t force the government to levy taxes on those people. Rather, it was the fact that the first five people wanted to all increase their utils. Since we started out in a Pareto optimal allocation of apple consumption paths, obviously when Old Al and Young Bob both improved their lifetime utilities, you had to know people down the road were going to take the hit. Haven’t you ever heard the expression, “There ain’t no such thing as free applesauce”?

DAVID BROOKS: (lip quivering) But…but…Krugman and all those guys led me to believe that it wouldn’t hurt our descendants!

LANDSBURG: You didn’t think levying taxes on people in the future would hurt them? And you call yourself a pundit?

DAVID BROOKS: Well I knew it would hurt some of our great-grandkids, but I thought the government would just take apples from one great-grandkid and give them to another.

LANDSBURG: Right, it did. Don’t you understand how our world works?

DAVID BROOKS: But I mean, I thought it would be a wash, as far as our great-grandkids collectively were concerned. I mean, Yglesias’ thing about the government defaulting, and it just being a wash…

LANDSBURG: Right, it would be a wash if the government had defaulted, say, in period 6. That act would hurt some people but help others, but wouldn’t make society richer or poorer on net.

DAVID BROOKS: Agghh! I’m going crazy here! So how did we end up making Frank through John worse off?! If we had defaulted, and you’re saying it’s a wash…?

LANDSBURG: Oh, I see what’s tripping you up. If the government had defaulted in period 6, it would have been a wash relative to the new scenario where Frank through John already had less utility. Once Al through Eddy had lived and died, and had each achieved more utility than 20, it was obvious that somebody from Frank through John would take a hit. But government tax and bond payment policies could redistribute the hit. For example, if the government had defaulted in period 6 and then levied no taxes, then Frank alone would have taken the full hit. Al through Eddy would have benefited, Frank would have gotten crushed, and George through John would have been unaffected (each consuming 100 apples per period). So Yglesias was right, defaulting on the government’s debt in a particular period can’t make society richer–if it did, then we’d all make side deals with each other and default! Duh. Seriously, you call yourself a pundit?

DAVID BROOKS: (tears welling up in his eyes) But…but…all the stuff about “apple output in any future period is always 200″… If the government takes an apple from one person, it can only give it to someone else…

LANDSBURG: Right, that’s all true. Why is this so hard for you? Look: You guys wanted to give Old Al 3 apples. Somebody had to get taxed to pay for it. You could have taxed the Young Bobs, but chose not to. Instead, you taxed Frank through John, and then the bond market brought that revenue forward (after discounting of course) by getting loans from young people. It’s not the debt per se that made your descendants poorer, it was the government’s decision to tax them instead of taxing the Young Bobs.

DAVID BROOKS: But all of that stuff they were saying about not shipping apples to other Excel tables…

LANDSBURG: Hey! I told you upfront that that was silly. But other than that non sequitur, everything else those Keynesians told you was perfectly true.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, right, now that you mention it, I do remember you saying that their focus on keeping the apples within the Excel table–in the hands of our descendants–was irrelevant. But it’s not like it was a casual aside of their case; they based their whole argument on that “insight” which you said was wrong. And by making me focus on physical apples, they convinced me that it was literally impossible for us to enrich ourselves at the expense of people in, say, period 9, because we only had 200 apples today, and no matter what, Iris and John were going to split up 200 apples then.

LANDSBURG: Hang on a second. Do you honestly mean to tell me you weren’t aware of how debt financing and overlapping generations work? You haven’t read Samuelson’s paper on Social Security?! And now you’re mad at Krugman and me, for not pointing this out to you before? Gee whiz, do you want us to lay your clothes out too in the mornings? You’re dumber than I thought. Maybe you shouldn’t be having more sex.

DAVID BROOKS: (hanging head in shame, cannot withstand Landsburg’s withering criticism any longer and turns to another, inebriated economist) What do you think?

GENE CALLAHAN: Yeah, Steve is right, and Murphy has just been saying one goofy thing after another. Look, we could have achieved the same outcome in terms of everybody’s utils, without using deficit finance at all. Instead, the government could have taxed Young Bobs 3 apples in period 1, then it could have taxed the Young Christys 6 apples in period 2, and so on. So none of this debate was really about whether we could impoverish our great-grandkids; of course we can! The issue has always been, is the debt the thing to blame. What conversation have you been in?

DAVID BROOKS: HUH?!? You’re telling me I missed the whole point of this debate?! The very thing I was worried would happen–that if we didn’t tax the Young Bobs in period 1, but instead paid for the transfer with a deficit, we would foist that burden onto our descendants–is exactly what happened! And I let Dean Baker and all those guys convince me I was stupid!

STEVE LANDSBURG: (aside) You are.

DAVID BROOKS: (turns to a grad student) OK, maybe a younger guy can help me out here. My head is spinning at this point.

DANIEL KUEHN: Well, I’m not really sure why you were surprised by the outcome. Didn’t Krugman let you know that this could happen? I mean, when he said “talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay apples to other children,” how could that not have tipped you off that the above scenario was possible?

This is the cost and the benefit that Murphy was talking about – costs and benefits on individual children, if you add up their whole lifetime income. But within each period you don’t have a transfer of resources.

Isn’t this the Krugman position? Winners and losers but no additional burden on any particular future time period? If you look at future income levels, that remains unchanged. If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.

DAVID BROOKS: (entire body is now shaking) How in the world are you describing what just happened?! Looking at the individuals from period 6 onward, it’s not true that “obviously some of them win and some of them lose.” THEY ALL LOST. Every single person who lived from period 6 onward was worse off, because of what we set in motion in period 1. No matter what those poor saps did, we and the next few generations had ensured that they collectively were going to be poorer than if we had just paid for Old Bob’s apples with a tax. And the way the government decided to handle this collective burden, in practice it wasn’t just that some of our descendants (like George and Iris) were worse off, but that others (like Hank and John) counterbalanced it by being better off. No, they were ALL hurt in this scenario. And yet Krugman et al. had convinced me that such an outcome was physically impossible.

DANIEL KUEHN: Ah, the problem here is that you’re mixing up terminology. Krugman has established, quite correctly, that the government in our world could make specific individuals in the future poorer, but not that it could make the country as a whole poorer in the future.

DAVID BROOKS: (pauses for several moments, as saliva begins to hang from his lower lip) Daniel, the country as a whole was poorer from periods 6 through 9.

DANIEL KUEHN: (sighs) No it wasn’t. What was national income in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: Huh?

DANIEL KUEHN: In terms of apples, what was the sum of everybody’s income in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: 200.

DANIEL KUEHN: Right. And if you guys in period 1 hadn’t started your deficit scheme, what would national income have been in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: (reluctantly) 200.

DANIEL KUEHN: Uh-huh. See what I mean? Krugman et al. were totally right–you guys in Period 1 didn’t make the nation poorer in period 6 or 7 or whatever. That’s physically impossible; national income in every period is always 200 apples.

DAVID BROOKS: But…but…even so, every single person from period 6 onward was made poorer by this whole thing.

DANIEL KUEHN: Yep, just like Krugman told you could happen.

DAVID BROOKS: (beginning to sob) No he didn’t Daniel… I, I, I don’t even understand what is happening at this point. I need to sit down. (sits in chair)

DANIEL KUEHN: There, there. The problem is, you keep switching in mid-argument between “the nation” and “people in the nation.” Sure, specific descendants at any future date could have been hurt by you guys in period 1, but not your descendants considered as a collective.

DAVID BROOKS: So, just to be clear: You agree with me that Krugman and the other Keynesians were telling me that the nation as a whole couldn’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9. You agree with me, that they said that was impossible?

DANIEL KUEHN: Yep.

DAVID BROOKS: (breathes a sigh of relief) OK, good, because Landsburg really had me doubting my sanity there for a moment. So–and I realize I have to do this in baby steps because this stuff is so hard for me to get–you agree with me, that Krugman misled me by claiming that the nation as a whole couldn’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9.

DANIEL KUEHN: No! What the heck is wrong with you? Krugman is right! The nation can’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9!! National income is 200 apples, with or without debt. C’mon man, I’ve got a wife to entertain. I can’t be here all day.

DAVID BROOKS: (resumes sobbing) But Daniel, how can it be that Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John were all made poorer? I just can’t understand how all this is possible. (blows nose)

DANIEL KUEHN: I told you before: You’re confusing the nation with the individuals making up the nation.

DAVID BROOKS: So when Krugman convinced me that it was physically impossible to make the “nation as a whole” poorer from periods 6 through 9, I was wrong to infer that it was physically impossible to make every single member of the nation poorer from periods 6 through 9?

DANIEL KUEHN: (shocked) Yeah, what the heck would make you infer that? When Krugman told you that the “nation as a whole” would have the same income from periods 6 through 9, you didn’t realize that this outcome was consistent with “every single person alive” in periods 6 through 9 being poorer? You honestly thought “the nation as a whole in period 6” was the same thing as “every person alive in period 6”? Boy Landsburg called it–you’re not too quick on the uptake, are you?

David Brooks throws a noose around a ceiling rafter. Then he stands on the chair.

DANIEL KUEHN: Hey! Get down from there. This is subtle stuff. Don’t be so hard on yourself.

DAVID BROOKS: (relents and steps down from chair) Yeah, I guess you’re right. I mean, if smart guys like Nick Rowe and Murphy could disagree with Krugman on this stuff, I shouldn’t be disappointed that I kept getting confused.

DANIEL KUEHN: Huh? What disagreement? Krugman, Rowe, and Murphy have all been saying the same thing all along.

DAVID BROOKS: (screaming) Aggggghhhhhhhh!!!!

Scene ends with Brooks in a straitjacket, being loaded into an ambulance while muttering about economists and apples. Ambulance driver turns and says to Brooks, “Sounds like a confusing story. Hey, wanna see something reeeaaaally confusing…?”

Screen shifts to a sharp man with a cigarette. He begins to speak. “Picture a world, where people only eat apples. A man consults alleged experts on government deficits, and is taken on a journey that ultimately shatters his mind–a journey that ends, in the Economist Zone.”

Spooky theme music begins playing as screen fades out.

Interview With the Director

When I first wrote the above, it was mostly intended to be humorous. However, even the act of writing it has shed new insights for me on this fiendishly subtle controversy.

Let me just say that what has happened here isn’t that “these guys were right” or “these guys were wrong.” The amazing thing is that–if we forgive people for slips of the tongue and missteps that don’t hurt their overall position–every viewpoint I’ve incorporated above, had a germ of validity. And yet, as I tried to show with the exasperated “David Brooks,” it seemed that these economists were contradicting each other.

If I were still a college professor, I would honestly invent a course just to have an excuse to play with that OLG model for hours on end, introducing more features like investment in future trees, altruism between generations, private bond markets, etc. I am still in slight shock from the possibilities that this debate has brought to my attention.

Let me close with one observation, just to make sure all of you understand why I think this is such a big deal: Krugman et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can’t reduce the sum of individual incomes earned in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time, subject to all the caveats about incentive effects and so forth. And yet, James Buchanan et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can reduce the (after-tax) incomes earned by every individual who is alive in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time. At first glance it seems that one of these camps must be wrong, but actually they are both right. But because those statements appear to be contradictory, people on both sides have been quite sure that the other guys were idiots or liars.

UPDATE: I just double checked my intuition on something, and yep it works. So let me report it, since it really helps in tying all of this together and getting a handle on what the #%)(#)($* happened in the numerical example above. Recall that I have Steve Landsburg in the script saying that the government in period 1 is giving Old Al 3 apples, and that it could have either taxed Young Bob at the time, or taxed future people. Now the thing is, the interest rate on government bonds in this world is 100%. So if the government wants to tax somebody 86 apples in period 6, for example, then in period 1 that future tax revenue only has a present-discounted value of about 2.69 apples. (That’s 86*(1/2)^5.) If you go through and calculate the PDV of the future tax levies from the perspective of period 1–discounting by 100% per time period–you will see that the future levies add up exactly to 3 apples. So the words I put in Landsburg’s mouth are totally correct, and that’s a very useful way to think about it, in my opinion. The overlapping generations and bond markets allow the present generation to fund transfer payments out of taxes that won’t be imposed for hundreds of years!

Recent Comments