Someone Explain To Me…

…how I am 7 slots behind Scott Sumner in a ranking of Austrian economics blogs? (HT2 some other guy who beat me too.)

How Does Brad DeLong Define Success?

[UPDATE below.]

I’m not sure, but it must be a low bar. In a recent, exhaustive critique of Hassett, Hubbard, Mankiw, and Taylor (HHMT)–who have written a “white paper” on the Romney economic program–DeLong is upset that these critics of Obama have pointed to a certain research paper to bolster their objection to the “cash for clunkers” program. (HT2 Daniel Kuehn) Here’s DeLong, first summarizing the HHMT position, and then critically responding to them:

HHMT: The negative effect of the administration’s ‘stimulus’ policies has been documented in a number of empirical studies. Research by Atif Mian of the University of California, Berkeley, and Amir Sufi of the University of Chicago showed that the cash-for-clunkers program merely moved new car purchases ahead a few months with no lasting effect.

[DeLong responds:] DOES NOT FOLLOW: Such policies are supposed to shift demand forward in time into periods where the crisis is acute from future periods in which, it is hoped, demand is less slack. When Mian and Sufi present their work, they characterize it not as showing the failure but rather the success of programs like CFC [cash for clunkers].

Now when I read this, I thought, “Ah, excellent. Here we have a pretty straightforward factual claim and counterclaim, and one that we can easily verify in 10 seconds with Google: Did Mian and Sufi in fact interpret their own work as showing cash-for-clunkers was a failure or a success?”

Here’s the abstract from Mian and Sufi’s paper:

Abstract:

A key rationale for fiscal stimulus is to boost consumption when aggregate demand is perceived to be inefficiently low. We examine the ability of the government to increase consumption by evaluating the impact of the 2009 “Cash for Clunkers” program on short and medium run auto purchases. Our empirical strategy exploits variation across U.S. cities in ex-ante exposure to the program as measured by the number of “clunkers” in the city as of the summer of 2008. We find that the program induced the purchase of an additional 360,000 cars in July and August of 2009. However, almost all of the additional purchases under the program were pulled forward from the very near future; the effect of the program on auto purchases is almost completely reversed by as early as March 2010 – only seven months after the program ended. The effect of the program on auto purchases was significantly more short-lived than previously suggested. We also find no evidence of an effect on employment, house prices, or household default rates in cities with higher exposure to the program.

I think I solved the mystery here. DeLong knows how he writes about people or programs with which he disagrees; accusations of perfidy and fascism come to mind.

So, since Mian and Sufi don’t say, “Why oh why can’t we have better Administration economic policies?!” DeLong interprets that as a ringing endorsement.

Last point: Forget DeLong for a moment. Go re-read the HHMT position (the top half of the first blockquote above), and then re-read the Abstract from the Mian and Sufi paper. It is almost verbatim.

And yet, DeLong blows a gasket and adds this to his list of misleading statements or outright lies (DeLong’s term) put out by HHMT.

UPDATE: Daniel Kuehn links to this article by Ezra Klein, who contacted some of the economists whose work was cited in the HHMT white paper. I didn’t hunt down the originals and compare with what Klein asked the people, but assuming Klein was being fair, it looks like HHMT misrepresented some of the research on which they relied. One of the people Klein contacted, was an author on the cash for clunkers paper. Notice though that even here, the guy’s response is (paraphrasing), “Oh, we weren’t criticizing stimulus plans in general. We were just saying the CFC didn’t do anything, but that was a $4 billion drop in the bucket. So you can’t generalize from that failed program, to the Administration’s stimulus policies in general.” Like I said, I am paraphrasing there, so go look at his actual position if you want.

“What Model Is Ben Bernanke Using?!”

The bitter von Pepe sends this John Taylor blog post from early July:

In a recent speech at Stanford (video here) former Wells Fargo Chairman and CEO Dick Kovacevich told the full story of how he was forced to take TARP funds even though Wells Fargo did not need or want the funds. The forcing event took place in October 2008 at a now well-known meeting at the U.S. Treasury with Hank Paulson, Ben Bernanke, as well as several other heads of major financial institutions.

In his speech, Kovacevich first described how he and the other bankers were told at that meeting that they had to accept the funds. He then paused and said to the Stanford audience: “You might ask why didn’t I just say no, and not accept TARP funds.” He then explained: “As my comments were heading in that direction, Hank Paulson turned to Chairman Bernanke, who was sitting next to him and said ‘Your primary regulator is sitting right here. If you refuse to accept these TARP funds, he will declare you capital deficient Monday morning.’ This was being said when we were a triple A rated bank. ‘Is this America?’ I said to myself.”

Kovacevich, in the Q&A period of his talk, apparently explained that he and others in the financial industry had been quiet about all this, because they didn’t want the government to crack down on their companies for talking back.

Now I’ve heard this tale before, but until this morning I never reflected on one crucial aspect of it: Ben Bernanke is sitting there, knowing that Paulson is relying on him–the Bernank–to punish people for not taking TARP funds. In other words, Bernanke didn’t spit his water out and say, “Hank, I do declare! The very idea that I would adjust my opinions on capital deficiency in this way! I am a former academic, this conversation disgusts me.”

So for all of the naive bloggers out there, who just can’t understand why Bernanke doesn’t implement the policies he advocated when he was writing journal articles… Is it because he is just a kind of shy guy?

No, I don’t think that’s it. Here is the “model” I think Bernanke is using.

Keira Knightley Has Been Naughty

I know, a cheap provocative post title–but at least I’m not putting up any pics.

This article explains:

The atheist actress, star of A Dangerous Method, said she is desperate to be Catholic because she would “just get to ask for forgiveness”.

She added: “It sounds much better than having to live with guilt.

“It’s absolutely extraordinary. If only I wasn’t an atheist, I could get away with anything.

“You’d just ask for forgiveness and then you’d be forgiven.”

I don’t know the young woman’s personality well enough to tell if she is being snarky or sincere in these quotes. But for sure, the people on Facebook passing this around with approval, were interpreting the episode as yet another arrow in their quiver against idiot Christians. I have a few comments:

(1) Notice how the Christian (or other theists to whom this would apply, but I can speak more knowledgeably about Christians) is stuck no matter what. If his religious views require him to do things that are considered unpleasant by the average secular American–like getting up to go to church on Sunday, abstaining from masturbation, waiting for marriage, etc.–then the atheist ridicules the silly superstitions for their ridiculous hindrance of enjoyment. Yet, to the extent that the Christian’s views provide earthly comfort, this too is taken as further evidence of just how wrong these views must be.

(2) Ms. Knightley is certainly correct: It is very comforting to truly believe you have been absolved of your guilt for past offenses. The older I get (not that I’m Yoda or anything) I think you can understand more and more of people’s actions as hidden responses to their fear and guilt. Well say what you will about Christianity, but believing in an omnipotent Being who loves you unconditionally and is willing to forgive your sins, and who has built mansions in paradise for those who want to accept the kind offer…that’s a pretty good recipe for containing your fears and guilt in the present.

(3) I did a little searching and it appears that atheists are very underrepresented in prison populations. However, I wonder if there are better studies that correct for obvious factors like IQ etc. Even here, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were still a negative correlation. My seat-of-the-pants stereotype is that atheists tend to be more principled and rational, and thus wouldn’t be petty criminals, if only because they would see how dumb that lifestyle is. Unfortunately, I think people who don’t fear any God do a tremendous amount of damage in positions of high power, where they’re the ones determining who goes to prison. (Don’t get me wrong, throughout history there have been plenty of powerful people committing awful crimes, believing they were doing what God had commanded.)

(4) I really don’t understand why people are so outraged at God’s willingness to forgive. In a regular relationship with your friends, lovers, or family members, both sides screw up all the time. Is it the mark of a good friend who says, “I still remember that time you screwed me over 13 years ago; I am never ever letting that go”? Would that be conducive to healthy human relationships? Or is it better to forgive and forget?

Aggression Is Counterproductive

This story was making the rounds in my circle of odd associates on Facebook:

When FBI and Joint Terrorism Task Force agents raided multiple activist homes in the Northwest last week, they were in search of “anti-government or anarchist literature.”

The raids were part of a multi-state operationthat targeted activists in Portland, Olympia, and Seattle. At least three people were served subpoenas to appear before a federal grand jury on August 2nd in Seattle.

In addition to anarchist literature, the warrants also authorize agents to seize flags, flag-making material, cell phones, hard drives, address books, and black clothing.

The listing of black clothing and flags, along with comments made by police, indicates that the FBI may ostensibly be investigating “black bloc” tactics used during May Day protests in Seattle, which destroyed corporate property.

If that is true, how are books and literature evidence of criminal activity?

To answer that, we need to look at the increasing harassment, surveillance, and prosecution of anarchists and political activists associated with the Occupy Movement.

In some cases, such as the May Day arrests in Cleveland, the FBI has been so desperate to arrests “anarchist terrorists” that it supplied them with bomb-making materials and used an informant to entrap them. The same thing happened in Chicago.

The motivation for these operations, and the instruction that “anarchist” means “terrorist,” is coming straight from the top levels of the federal government. As I recently wrote, new documents show that the FBI is conducting “domestic terrorism” training presentations about anarchists.

The FBI presentation described anarchists as “criminals seeking an ideology to justify their activities.”

This is the guilt-by-association mentality that is guiding FBI and JTTF assaults on political activists; if agents find “anarchist literature” in a raid, it is evidence of criminal activity because anarchism, in and of itself, is criminal activity.

The Seattle grand jury may or may not be investigating May Day protests. What’s clear, though, is that the grand jury is being used as a tool in this criminalization of those suspected as “anarchists.” Grand juries are secretive processes that are frequently used against political activists in order to acquire information. They are fishing expeditions. If activists refuse to testify about their personal beliefs and political associations, they can be imprisoned. Jordan Halliday, for example, was recently released after serving more than six months in prison (and being imprisoned once already for four months) for asserting his First Amendment and Fifth Amendment rights and refusing to provide information about the animal rights movement.

A police state is coming, make no mistake. But engaging in petty acts of vandalism and especially violence only bring it that much quicker. The average person reading the above is going to be searching really hard for the “explanation,” since Americans have been taught to believe this is a free country. I mean, we all know the government wouldn’t arrest somebody just for subversive ideas.

And, after looking for a bit…yep! The average American will find it. The police are just trying to break up a dangerous threat, because these anarchists have definitely vandalized property and generally behaved like hooligans, as anyone with a TV knows.

I’m not blaming the victim here, I’m just stating a fact. It’s amazing how many hardcore revolutionaries are, on the one hand, extremely jaded, and yet on the other so delightfully naive (like thinking that attacking a Starbucks will chafe the State).

Life Insurance, the Forgotten Savings Vehicle

Most Americans today know precious little of their country’s history, besides things like certain U.S. presidents and big wars. For example, most Americans don’t know that because of Constitutional concerns, the Eisenhower Administration had to cite the need to quickly move tanks and troops around to fend off an invasion, as a national security justification for building the interstate highway system. Can you possibly imagine someone challenging the federal government’s authority to fund highways in today’s political climate?

Another example is our nation’s monetary and banking system. Americans are vaguely familiar with the fact that the dollar used to be backed up by gold, though hardly anybody could speak for more than a moment about how this system actually worked, and what its rationale was. Yet if few Americans know about the gold standard, fewer still understand that there were large stretches when the U.S. operated just fine without a central bank. And for those who, somehow, manage to recall from a high school or college class that the Fed was founded in 1913, their teachers almost certainly never pointed to the awkward fact that the stock market crash of 1929, and the ensuing Great Depression, happened deep into the Fed’s watch.

Along with inconvenient facts such as these, another tidbit swept into the dustbin of history is that Americans used to rely on life insurance as a major savings vehicle. This sounds perhaps shocking at first, but remember the scene from It’s a Wonderful Life, when George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart) is down on his luck and runs to the greedy Mr. Potter for help. What does Bailey bring to Mr. Potter as an asset? Why, his life insurance policy.

This scene seems odd to many modern viewers; I remember being puzzled when I first saw the movie. This was because I only thought of term life insurance, rather than permanent (or cash-value) life insurance. The modern financial gurus, such as Dave Ramsey and Suze Orman, counsel their listeners unequivocally to avoid permanent life insurance as a terrible investment, if not an outright scam.

Yet it was not always so. Here is the great economist Ludwig von Mises, writing matter-of-factly in his 1949 treatise Human Action:

For those not personally engaged in business and not familiar with the conditions of the stock market, the main vehicle of saving is the accumulation of savings deposits, the purchase of bonds and life insurance. (p. 547)

and later on

[Under capitalism, even] for those with moderate incomes the opportunity is offered, by saving and insurance policies, to provide for accidents, sickness, old age, the education of their children, and the support of widows and orphans. It is highly probable that the funds of the charitable institutions would be sufficient in the capitalist countries if interventionism were not to sabotage the essential institutions of the market economy. Credit expansion and inflationary increase of the quantity of money frustrate the “common man’s” attempts to save and to accumulate reserves for less propitious days. (p. 834)

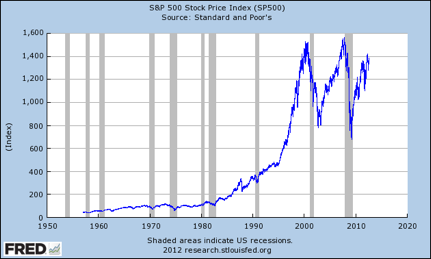

The notion of life insurance as a savings vehicle was displaced by mutual funds, which had become more accessible to the average household, and looked very attractive by the late 1970s. The high interest rates and inflation of this era—the result of government manipulation in the financial markets—suddenly made conservative life insurance look boring and sluggish. Americans were steered by the “experts” into Wall Street, and federal tax laws—which levy large penalties on all assets except the ones exempted by the IRS—only reinforced the transformation of the conventional wisdom.

But is the stock market really a safe place to put one’s genuine savings, as opposed to the funds one considers as investments? In terms of economic theory, this distinction fades away, because there is no such thing as a perfectly safe investment. But in everyday practice, there is a definite difference between wealth that is supposed to be bedrock savings, versus more speculative investments that offer the chance for higher return but come with greater risk. With this framework in mind, how should one classify the average American’s 401(k) or other tax-advantaged retirement vehicle based on “the market”?

Beyond the wild volatility of allegedly “diverse” stock market holdings, is the fact that government regulations put your assets virtually in prison until official retirement age. With few exceptions, there are severe penalties for early withdrawal, and you can’t even use such “advantaged” funds as collateral for loans.

If the stock market, whipsawed about by Federal Reserve policy, is too risky for one’s genuine savings, the commercial banking sector nowadays is useless as well, with interest rates at historic lows—again because of the Fed. Moreover, what little interest you do earn on CDs or savings accounts, is then taxed at “progressive” rates.

In this bleak environment, many have flocked to the precious metals—the market’s original money, before they were driven underground by government measures—as the last refuge. I myself have urged my readers to acquire stockpiles of gold and silver, and I continue to do so. However, although the precious metals provide an excellent hedge against inflation, they too are subject to price volatility, they don’t generate an income stream, and they are subject to capital gains taxes. (Plus, there was that incident in 1933 when the federal government forcibly seized everybody’s gold under threat of fines and up to ten years of imprisonment.)

After several years of study—reading textbooks, interviewing actuaries, and attending seminars—I have come to believe that the old-timers were on to something: Life insurance, especially with its currently favorable tax treatment, is an excellent savings vehicle. Not only does it allow you to conservatively store your wealth in a relatively safe place, but you can instantly access it through “policy loans” from the insurance company (with your policy’s underlying “surrender cash value” serving as collateral).

I realize there are many knee-jerk reactions to this proposal, including the catchy slogan, “Buy term and invest the difference.” In future posts I will tackle these objections, because I have spent much time on them and believe they are spurious. For now, let me close with these thoughts from one of the world’s current experts on monetary and banking theory, economist Huerta de Soto:

The institution of life insurance has gradually and spontaneously taken shape in the market over the last two hundred years. It is based on a series of technical, actuarial, financial and juridical principles of business behavior which have enabled it to perform its mission perfectly and survive economic crises and recessions which other institutions, especially banking, have been unable to overcome. Therefore the high “financial death rate” of banks, which systematically suspend payments and fail without the support of the central bank, has historically contrasted with the health and technical solvency of life insurance companies. (In the last two hundred years, a negligible number of life insurance companies have disappeared due to financial difficulties.) — Jesús Huerta de Soto, Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles (Auburn, AL: The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009), p. 590.

My Two Cents on Caplan’s “Proof”

[UPDATE below.]

I saw this post from Bryan Caplan when I was jet-setting to Vegas, and thought something was really wrong with it. But I haven’t had time until now to write it up. Here’s Bryan:

When economists explain marginalism, students often object, “But surely no one ever changes his behavior over a single penny.” However, they’re provably wrong. If “no one ever changes his behavior over a single penny,” raising your price by a penny automatically increases your profit. So does raising your price by another penny. And another penny. And another penny… Any firm could earn infinite profit by sequentially raising its price, one penny at a time. Since this absurd, the premise must be wrong. People can, do, and must occasionally change their behavior over a single penny.

Wait, there’s more. On the typical day, most firms don’t raise their prices. Given the plausible assumption that firms want to make as much money as possible, we can infer that every firm expects that raising any price by a penny would lead to lower profits. This is only possible if every firm expects that raising any price by a penny would change some customers’ behavior.

The lesson: Behavior that responds to a one-penny change isn’t just a theoretical curiosity; unless price-setters are deeply mistaken about their own markets, behavior that responds to a one-penny change is all around us, always has been, and always will be.

I don’t know who originated this one-penny proof. I suspect authorship is lost in the sands of time. No matter. The author, whoever he may be, created something great: A simple, timeless, and virtually bullet-proof argument about all human behavior and pricing decisions. How many papers in the latest AER can claim anything remotely comparable?

Sorry Bryan, but not only am I not impressed by the rigor of this demonstration…I don’t even think it’s right.

Bryan is assuming his conclusion, without apparently realizing it: Critics challenge the notion that people (they have in mind consumers) might care about changes of one penny, and Bryan responds with an argument that assumes people (he has in mind producers) care about changes of one penny.

Look, the quickest way for me to make my point is to replace every occurrence of “one penny” in Bryan’s argument with “one-quadrillionth of a penny.” Did I just prove to you that everyone in the economy is acutely sensitive to price, down to the one-quadrillionth of a penny? Are market prices what they are right now, and not one-quadrillionth of a penny higher, because there is at least one person who would lower his purchases at that higher price?

If my point above seems too cute for you, switch to a more straightforward claim: I personally round off to the nearest dollar when I fill in the tip at a restaurant. In other words, I will calibrate the tip such that the final tally is a whole dollar amount. It’s definitely not the case that I would have ordered more or less food, depending on if the price of the entree is $12.99 versus $12.98.

In some markets, pennies matter. For example, when people are shopping for gasoline, they definitely pay attention to the posted price per gallon, down to the penny. But when someone is in the market for a new SUV, I don’t think pennies come into play at all.

Note that I’m not challenging Bryan’s basic conclusion; I’m not making an argument against marginalism per se. I’m just saying I don’t find Bryan’s “one-penny proof” very compelling.

UPDATE: Kavram in the comments write:

Skylien got it right. If marginal pennies were truly inconsequential the fact that so many market prices (notably installment payments for infomercial products) end with .99 would be one of the greatest coincidences known to mankind.

Actually, this is evidence in my favor, and massive evidence against Bryan. If prices were set by “rational” forces of supply and demand, you would expect an uniform distribution of trailing digits. In other words, 1% of the goods and services should end with a price of .00, another 1% should end with .01, etc.

The fact that in some markets, prices end with .99 means that something besides Caplan’s mechanism is at work. Yes, in a tautologous sense, the producers of infomercial products charge $19.99 because they think that if they charge $20.00 their sales will go down. But, if they charged $19.98 their sales would go down too! Worse yet, if they charged $19.72666 (and they expressed it like that, in the ad), then they would probably sell zero units because the average late-night viewer would be freaked out by that.

So, did I just prove that demand curves slope upward? Is this a Giffin good, perhaps? I mean, here we have a case where the seller makes more profit, by charging a higher price.

To reiterate, I am not claiming that market prices are random. Yes, they are what they are for a reason; human beings consciously agree to terms, and so market prices must “come from” humans somehow. What I am claiming is that these prices aren’t the simple product of intro-level profit and utility maximization, in the way Caplan believes. If he tells his students, “All prices in a market economy are set at that exact level, such that a one-penny increase in price would cause at least one buyer to fall out of the market and thus lower profits,” then I agree with any student who says, “Are you nuts?!”

Non-Conformists

According to my anecdotal evidence, David Friedman and I are the only economics bloggers who ignored the 100th anniversary of Milton Friedman’s birth. We focus on ideas, not people. We follow our hearts, not the crowd. Where others run, we walk. Where others drink, we slurp. Others write of anarchy; we live it.

Recent Comments