Mediating a Couple Arguing About Money

My friend and his wife are having a major disagreement over their household finances. He is self-employed (I don’t want to be more specific and tip some readers off as to his identity) and does one-off projects for clients. He relies on advertising and word of mouth to generate new leads.

Anyway, he asked me to chime in on the disagreement. I have my opinion, but I want to let you guys comment as well, to see if I’m missing anything. I’m going to change some of the numbers a bit for his privacy, but the below summarizes the spirit of the argument:

WIFE: Look, you really have to cut back on your business expenses. Our househeld debt is up 50% since you started your aggressive advertising campaign in early 2009.

HUSBAND: This is really stupid. How many times are we going to have this argument? Look, the advertising is the only thing that saved us. All my clients were dropping off like flies when the crisis struck in late ’08, remember? Who knows how broke we would have been, had we not spent that money?

WIFE: Well, we’re going to keep having the argument because you keep driving us deeper into the red. I never agreed with your premise that spending 20% more as your revenues collapsed was a good idea. I can’t believe I let you talk me into that.

HUSBAND: Huh? Eventually the revenue turned around, just like I said it would. And now that we’re following your advice, by slashing the advertising budget, we’re getting the predictable results–racking up more and more debt, just like I said we would.

WIFE: What the heck are you talking about?! We didn’t cut the advertising budget.

HUSBAND: Sure we did. As a percentage of my business’ potential revenues, we’ve slashed our spending by more than 50% since 2011.

WIFE: What kind of crazy accounting are you looking at? We’ve done no such thing. As a share of revenue, the advertising–

HUSBAND: Zip it! You’re not listening, as usual. I said as a share of potential revenue.

WIFE: What the hell is “potential revenue”?!

HUSBAND: It’s how much the business would have earned in each of the last three years, had you listened to my advice back in 2009.

So, decide which spouse you agree with. Then read this recent Krugman blog post.

Jon Stewart Makes Fun of CNN

Wednesday Is Fight Night

Murray Sabrin wanted me to pass this along to any readers who might be near Ramapo College:

War and the Fed

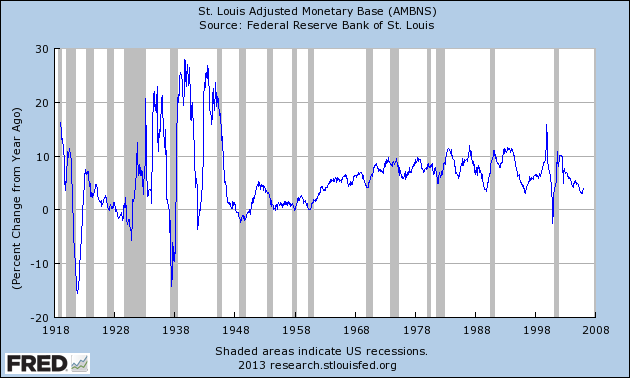

I’m going to be on Scott Horton’s radio program in a few minutes to talk about the connection between central banking and war. Here are two charts to supplement the interview. The first shows year/year percentage increases in the Consumer Price Index, while the second shows year/year percentage increases in the monetary base.

I think it’s pretty clear that during the World Wars the Fed played a significant role. (If you zoom in, I think you can also see patterns for Korea and Vietnam, but I have to do it again since the last time I checked was a couple of years ago.) What happens of course is that the Fed soaks up far more government debt than the private sector would be willing to absorb, allowing the government to spend more while waging war.

There’s no conspiracy here: Critics of the gold standard often explain that it would tie the government’s hands in a national emergency such as a war. Even Milton Friedman said something along these lines in one of his pop books.

The Japanese Experiment

“Tyler Durden” at ZeroHedge is as excited as a kid on Christmas Eve, thinking that the Bank of Japan has finally “lost control” because of the breakout of 10 YR Japanese government bond yields (doubling in 4 hours and triggering circuit breakers).

Let me make a falsifiable prediction of which I am certain: No matter what happens, Scott Sumner and other committed market monetarists will not admit that their plan failed and that the critics hitting them from an Austrian perspective were right.

For example, let’s say the BoJ’s new commitment to massive monetary expansions plays out in textbook Mises/Hayek fashion. There is a boom for a few years, then when CPI starts rising too rapidly the BoJ raises rates and Japan plunges back into an awful depression.

Clearly, Scott will blog at that time:

[HYPOTHETICAL SUMNER BLOG POST FROM 2016: “I cannot believe we’re going through this again. Finally the BoJ started taking my advice back in late 2012 / early 2013. We had several years of rising NGDP, which in turn didn’t destroy the yen as Peter Schiff said, but in fact led to rising real GDP–the best economy in decades. Then, because CPI broke 5% (which was mostly due to one-off events, as I’ve blogged about here and here), the BoJ tightened, leading to the biggest drop in NGDP since the 2008 crisis. Unemployment shot up to 9% after NGDP growth began slowing. How many historical examples do we need to see, that show awful recessions are caused by tight money? And yet the inflation-hawks continue to beat their drums.”

By the way, I’m not even saying the above is evidence that Sumner is a bad guy. Macroeconomics has so many moving parts, that it’s virtually impossible to look at a five-year period and conclude what “the objective lesson” is. You can tell just about any story you want, Austrians included.

My Parting Remarks on Scott Sumner and Interest Rates

Now that I had time to carefully read Scott’s response to my initial post on Japan, I have backed off a bit. I still think he is being slippery, but he was clearer in his response than I initially thought. So, my reaction in turn was not very helpful, and I can understand why Scott and his fans would dismiss me as an annoying gnat.

In this final post, let me summarize why I think he’s being slippery–engaging in the Scott Sumner Shuffle.

1) The BoJ announced a major monetary expansion, and Scott quoted a news article as if it confirmed his worldview.

2) I argued that this was weird, since Scott has consistently argued that looser money would lead to higher long-term yields, not lower.

3) Scott responded in a post that opened with these lines: “I often point out that on a few occasions easy money policy announcements have actually raised long term bond yields. But that’s obviously not always true.”

So, I am here to say that that way of framing his past writings is simply not true, and was the crux of our spat today. In the two sentences I’ve quoted above, Scott makes it sound like he says, “Hey, did you know that it’s theoretically possible that a surprise announcement of more asset purchases could actually raise long-term yields?! Really! It’s even happened a few isolated times in history!”

But no, that’s not at all what Scott has been saying over the years. Or at least, I can point to a few examples where he said something much stronger. Remember, the reason I know about this quite vividly, is that I was on the receiving end off Scott’s learning stick when he thought I denied the possibility of such things. Here we go:

==> On 12/26/12 Scott wrote: “People who pay attention to monetary policy know that easy money often raises long term interest rates. We have lots of high frequency data showing this (expansionary monetary surprises often raise long term bond yields)…”

==> On 12/12/12 Scott wrote: “[O]nce again Fed stimulus raises interest rates and lowers bond prices…” So that phrase “once again” means that this is a common thing. You wouldn’t say, “Once again, man bites dog.”

==> And the smoking gun: On 12/7/12, specifically in response to me (by name), Scott wrote a post with the title “If I Buy T-Bonds, Their Price Rises. If the Fed Buys T-Bonds, Their Price (Usually) Falls.” It was this post title that made me think that Scott Sumner believed that if the Fed buys T-Bonds, their price usually falls. Perhaps I read too much into it…

For extra clarity, from that post itself Scott says:

I notice that lots of commenters insist that bondholders gain when the Fed injects money by buying bonds. Even if this were true, it would have no bearing on my criticism of [Sheldon] Richman…But there’s a much bigger problem with this fallacy. It’s unlikely that monetary injections would raise bond prices at all.

and later

Do monetary injections always reduce bond prices? No, just most of the time. Obviously there are special cases that relate to how the injection changes expected future policy, and very small effects depending on which maturities are purchased. But the dominant effect is that more money means lower bond prices.

OK? Clearly Scott was lecturing me (yes, by name, I’m not pulling a Carly Simon here) on the fact that the default, normal case–in both theory and history–was for long-term bond yields to rise in response to an expansionary monetary surprise.

So today, when Japanese 10-year yields fell to record lows on the BoJ’s announcement, I pointed out that this was a little awkward for Scott.

And in response he said, “I often point out that on a few occasions easy money policy announcements have actually raised long term bond yields.”

That, my friends, is the Scott Sumner Shuffle–not to be confused with a Krugman Kontradiction.

Sumner Responds

[UPDATE below.]

It’s getting late and I’m working on a deadline, so perhaps this is foolish of me. I feel like when I’m playing the computer in chess and it makes what seems to be a really dumb move. Do I pounce, or should I be cautious and assume I’m missing something subtle?

Anyway, here’s what Scott Sumner said in response to my post blasting him about Japan:

Some commenters (such as Bob Murphy) seem to think I believe that nominal interest rates are a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy. That’s probably because I often quote Friedman saying that ultra-low nominal rates are a sign that money has been tight. I still believe that, but Friedman didn’t think rates were was a reliable indicator of the current stance of monetary policy, and neither do I. [Bold in original.]

And my punky response:

Just to avoid future misunderstandings, [Scott, you think that] the stock market and foreign exchange market are reliable indicators of the *current* stance of monetary policy, right? In response to a surprise central bank announcement, you think speculators almost immediately update prices of stocks and currencies. But they wait a year or two before turning their attention to bonds?

(Yes I’m being snarky but this is the Internet. If I ever become more famous than you Scott I will be really polite.)

UPDATE: Primarily because I have a deadline I should be working on, I am going through Scott’s archives from the period where he took on Sheldon Richman and me, because I was quite sure this is the time where I got my “misunderstanding” of his position. Here are some examples of where I got the wacky notion that Scott believed if the government switched to easier money, then long-term interest rates would respond quickly (just like Scott thinks every other thing in the economy responds immediately, because of efficient markets).

==> On Dec. 26, 2012, in a post entitled “Recognizing easy money” (apropos, yes?) Scott wrote:

People who pay attention to monetary policy know that easy money often raises long term interest rates. We have lots of high frequency data showing this (expansionary monetary surprises often raise long term bond yields) and low frequency data (long periods of accelerating M2 growth usually result in higher inflation and higher bond yields.)

But most people don’t understand this, probably because they equate the terms ‘easy money’ and ‘low interest rates.’ So the claim that easy money raises rates leads to one of the “that does not compute” moments of puzzlement. [Bold added, to show this is an immediate effect. It is a weird type of “monetary surprise” that happend in the past.]

==> But that’s nothing. Here’s the post I was looking for, from Dec. 12, 2012, titled “Take that, Cantillon effect fans”:

Hot off the wire, once again Fed stimulus raises interest rates and lowers bond prices:

[Here Scott quotes from a financial news article:] Treasuries fell after the Federal Reserve said it will buy $45 billion a month of U.S. government debt, expanding its asset-purchase program while linking its main interest rate to unemployment and inflation.

Only the Fed can make the price of something fall by purchasing more of it. Ironically, the Fed wants to lower long term interest rates.

So let’s remember the context here. This event happened about a week after Scott and I had been crossing swords over Cantillon effects, where Sheldon and I were saying that (other things equal) when the Fed buys an asset, it pushes up that asset’s price and benefits the current owners. Scott kept pointing out how ignorant we were, and said that usually when the Fed creates new money to buy bonds, long-term yields go up because of expected price inflation.

Then, a week later, the Fed announced QE3 (right? I’ve lost track of the dates now), and Treasuries responded to that announcement by falling in price. Scott pointed to this as a feather in his cap.

Clearly, Scott is now inventing stuff when he says that he never claimed nominal bond yields are an indication of investor expectations about *current* monetary policy. He just said it twice above, and moreover that is a critical part of his worldview. I.e., Scott famously rejects the idea that we need to “wait and see” if a monetary policy worked; we look at the immediate impact on various market data.

So it’s odd that Scott celebrated the BoJ’s ability to push 10-year government bond yields down to record lows. That suggests investors now anticipate a combination of lower price inflation and/or real economic growth. How is that a success, in Sumner’s book?

P.S. I know Scott never claimed that low nominal long-term bond yields were 100% proof of tight money. But he *did* say, “near-zero interest rates are an almost foolproof indicator that money has been too tight,” and above I’ve documented him showing how when things move *immediately* in the direction he wants, then he claims it as further evidence that he is right and his critics are wrong. All in all, I don’t think this is merely my failure to read carefully, I think this is the Sumner Shuffle.

More Journalists Schooling Austrian Economists on Monetary Theory

I have asked George Selgin to please destroy this properly, but for now, behold:

Goodhart points out, however, that Menger is just wrong about the actual history of physical money, especially metal coins. Goodhart writes that coins don’t follow Menger’s account at all. Normal people, after all, can’t judge the quality of hunks of metal the same way they can count cigarettes or shells. They can, however, count coins. Coins need to be minted, and governments are the ideal body to do so. Precious metals that become coins are, well, precious, and stores of them need to be protected from theft. Also, a private mint will always have the incentive to say its coins contain more high-value stuff than they actually do. Governments can last a long time and make multi-generational commitments to their currencies that your local blacksmith can’t.

I’m trying to come up with an analogy, to show what other enterprises should be monopolized by the government as a way to overcome incentives for bad behavior, but I am at a loss. I can’t believe someone wrote the above paragraph, particularly in an article claiming to knock someone upside the head with the real facts of history.

Recent Comments